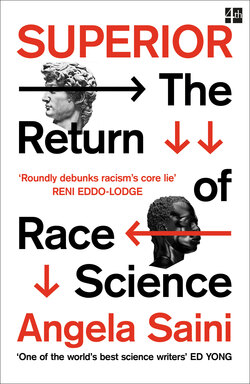

Superior

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Angela Saini. Superior

Copyright

Praise for Superior:

Dedication

Prologue

1. Deep Time. Are we one human species, or aren’t we?

2. It’s a Small World. How did scientists enter the story of race?

3. Scientific Priestcraft. Deciding that races could be improved, scientists looked for ways to improve their own

4. Inside the Fold. After the war, intellectual racists forged new networks

5. Race Realists. Making racism respectable again

6. Human Biodiversity. How race was rebranded for the twenty-first century

7. Roots. What race means now in the light of new scientific research

8. Origin Stories. Why the scientific facts don’t always matter

9. Caste. Are some races smarter than others?

10. Black Pills. Why racialised medicine doesn’t work

11. The Illusionists. Down the rabbit hole of biological determinism

Afterword

References. Prologue

1 Deep Time

2 It’s a Small World

3 Scientific Priestcraft

4 Inside the Fold

5 Race Realists

6 Human Biodiversity

7 Roots

8 Origin Stories

9 Caste

10 Black Pills

11 The Illusionists

Afterword

Index

Acknowledgements

By the same author

About the Publisher

Отрывок из книги

‘This is an essential book on an urgent topic by one of our most authoritative science writers’

SATHNAM SANGHERA, author of The Boy with the Topknot

.....

Some of the very oldest human sites in Europe bear evidence of fairly sophisticated cave art. So as a result of indexing, early archaeologists digging on their doorstep logically assumed that art and the ability to think using symbols and images must be a mark of human modernity, one of the features that make us special. But the first Homo sapiens arrived in Europe only around 45,000 years ago. When researchers then excavated far earlier sites in Africa, some as old as 200,000 years, they didn’t always find the same evidence of symbolic thought and representational art. ‘The archaeologists came up with a way to square this,’ says Shea. ‘They said, well, okay, you know these ancient Africans, Asians, they look morphologically modern but they aren’t behaviourally modern. They’re not quite right yet.’ They decided that although such people looked like modern humans, for some reason they didn’t act like them.

Rather than rethinking what it meant to be a modern human – perhaps taking out the requirement that Homo sapiens began making art immediately upon the emergence of our species – the rest of the world’s history became a puzzle to be solved. It’s a misstep that still has repercussions today. If art is what sets our species apart from Neanderthals and others, then at what point did we actually become our species? Was it 45,000 years ago when we see sophisticated cave art in Europe, or 100,000 years ago when, we now know, people used ochre for drawing? And if Neanderthals or other archaic humans turn out to show evidence of symbolic thought and to have made representational art, will we then have to call them modern too? ‘Behavioural modernity is a diagnosis,’ says Shea. All the archaeologists can think to do is ‘rummage around looking for other evidence that will confirm this diagnosis of modernity’.

.....