A Sephardi Life in Southeastern Europe

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Aron Rodrigue. A Sephardi Life in Southeastern Europe

Отрывок из книги

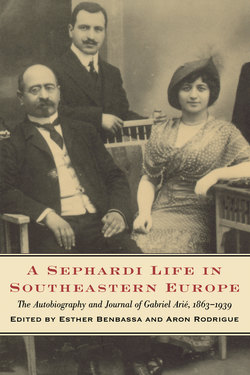

A Sephardi Life in Southeastern Europe

The Autobiography and Journal of Gabriel Arié, 1863–1939

.....

Family and illness were the two poles of the life of this man and were closely linked. Arié believed that the family transmitted illness. He blamed his grandparents and parents for having passed illnesses on to him. He attributed his physical defects to them. He also evoked his father under the sign of illness. The focus of his ills was thus the family. But he did not succeed in doing without family and established relations of a familial kind with the Other. The relations he had with the teacher Mme Béhar, with the Alliance, with his future in-laws in Ortaköy, and with his uncle in Galata were all of a kind. He created a large family, lived for a time with his mother and wife in the same house, brought mother, brother, and sister to Izmir after the death of his father and provided for their needs, married off brothers and sisters, took care of them when their material situation was not as good as it might have been, worried about their material future, brought his family to Davos during his illness, brought his children into his business, and maintained long-term relationships with the different members of his family throughout his life. As a newlywed, Gabriel Arié lived with his parents; later, his mother, younger brother, and sister moved in with him. He shared the same building with his brother, and then his son came to live with him. We thus have a portrait of the typical Sephardi family, where young and old lived together. Arié tried to break with this practice numerous times, but in the end was obliged to go along with it. There was a gap between his own aspirations and local contingencies. This was not yet the framework of the contemporary urban family of the nineteenth century, where intergenerational solidarity dissolved.71

To a great extent, Gabriel Arié also conducted his business with members of his family, and later with his descendants. His sense of family was very developed and his penchant toward egocentrism did not prevent him from managing his family relationships as a powerful and omnipresent—but attentive—paterfamilias, preoccupied with the material future of those close to him. Like any bourgeois, he made it a duty to place his children on a firm financial footing and made sure they did not lose their class standing by the choice of an occupation or spouse whose status was unworthy of them.72 In fact, his male children, like himself, made careers in insurance. Arié’s solicitude extended to his less immediate family as well. First Davos, then summer stays in vacation spots abroad and in Bulgaria, became occasions for family reunions. Everyone moved through these places in a continual coming and going, which pointed to both the wealth of the family and the affection that linked its members together. Summer tourism in the mountains and spas or in the country became a habit, as in the European bourgeois family of the nineteenth century.73

.....