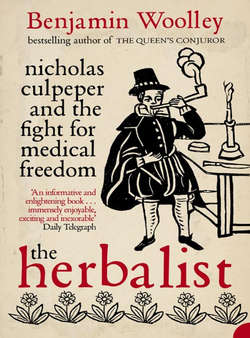

The Herbalist: Nicholas Culpeper and the Fight for Medical Freedom

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Отрывок из книги

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY

However, hidden in the undergrowth is a startling story, entangled with so many others, with the struggles of the woodturner Nehemiah Wallington to survive the plague, with the mischievous prophesies of the astrologer William Lilly, with the Olympian struggles and self-belief of King Charles I, and most of all with the anatomical explorations and loyal ministrations of the King’s doctor William Harvey, the Isaac Newton of medical science and model of medical professionalism. Like the Cleavers and other discarded weeds championed in his Herbal, Nicholas certainly had ‘some Vices [but] also many Virtues’. His vices were well known, itemised by friends as well as his many enemies: smoking, drinking, ‘consumption of the purse’. But he was also audacious and adventurous. He championed the poor and sick at a time when they were more vulnerable than ever. He took on an establishment fighting for survival and ferociously intent on preserving its privileges.

.....

Underlying this tough message was Attersoll’s belief in predestination. This was one of the central tenets of Protestant theology, and at the time Attersoll was writing accepted by both the established Church and Puritan radicals.33 God, went the argument, must know in advance who will be saved – the ‘elect’, as theologians called them – and who will be damned. If he did not, then it meant he did not have perfect knowledge of the future, which suggested that his divine powers were limited. Attersoll found confirmation of this principle in the Book of Numbers. The book took its name from the census performed by Moses when the Israelites entered the wilderness of Sinai. ‘We learn from hence,’ argued Attersoll, ‘that the Lord knoweth perfectly who [his people] are.’ But his people, being but human and without perfect knowledge, do not know if they are among the elect. The signs were in their behaviour, which showed whether they tended towards godliness or wickedness. For example, rebellious acts, obstructions in the river of godly authority flowing from heaven, were symptoms of a wicked disposition.

In this fateful atmosphere, every act was subjected to providential scrutiny. The most trivial prank could mean the child was doomed, as deadly a sign as a cough indicating consumption. And whichever destiny was signified, salvation or damnation, nothing could be done about it. ‘God keepeth a tally … & none are hidden from him, none escape his knowledge, or sight.’

.....