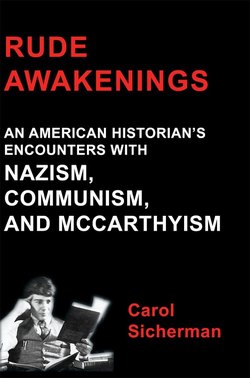

Rude Awakenings: An American Historian's Encounter With Nazism, Communism and McCarthyism

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Carol Jr. Sicherman. Rude Awakenings: An American Historian's Encounter With Nazism, Communism and McCarthyism

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

1. Prologue

The nature of the evidence

Diarists and letter-writers

2. Harry’s Home, Harry’s Harvard

Louis Marks in the private sphere

Louis Marks in the public sphere

“Darling Harry” at Fieldston–the route to Harvard

Undergraduate studies

Jews are “better off at Harvard”

3. A New Young Scholar in the (Old) World

Starting in Berlin

The values of Harry’s social circle

Paul Gottschalk, alias P.G

The idea of “Germany”

The University of Berlin

Assessing the instructors

Reaping the benefits

Extracurricular activities

Travels in Europe

Paying attention to current events

4. Germany 1933

Hitler becomes chancellor

The Reichstag fire

Consolidating Nazi control

Finding out what was happening

The “gentlemen” take charge

On vacation: exploring opinion in the hinterland

Changes in educational institutions

Atrocity stories

German and Jewish

The Meyers

The Hirschbachs

The Gottschalks

Harry as confidante and tutor

Ernst Engelberg: a decisive friendship

Gustav Mayer172

Hajo Holborn

Dietrich Gerhard

5. The Dispersal of the Berlin Friends

Grete and Ernst Meyer

The Meyer children24

Grete and Ernst in the New World

Paul Gottschalk51

The other Gottschalks

The Hirschbachs

The Freyhans

Gustav Mayer and his family

Dietrich Gerhard

Hajo Holborn

Ernst Engelberg108

6. Harry and the Communists. Choosing sides

Why Harry joined

Harry in the NSL and YCL

The peace strikes

Harry’s activist colleagues

Politics and love

The demonstrations against the Karlsruhe

The Hanfstaengl affair

Harvard and German universities under the Nazis

Harry and Bunny in love

Why Harry and Bunny left

7. The Knock on the Door: Harry before HUAC

The background

Accusations at UConn

The Committee of Five

Zilsel’s testimony

Emanuel Margolis: a reminder from the past

Margolis and the Committee of Five

The risky profession of social work

A friendly witness

Harry in “the odious role of an informer”

Why did HUAC persist?

8. Harry as an Academic

Starting a career

Harry as teacher and colleague

Paying the price: Harry’s career

Harry’s professional writings

Timeline of Events in Germany

Notes. Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Timeline

Bibliography

Отрывок из книги

A number of people have been vital to my work on this book, which originates in the papers of Harry J. Marks, my father. The family of Ernest Engelberg, an age-mate and friend in Harry’s Berlin days, has been generous with hospitality and information. A visit in 2005 to Engelberg, then ninety-six years old, his son (Achim), and wife (Waltraut) gave powerful impetus to the research. Achim later made a gift of his book about German refugee intellectuals who returned to Germany. Engelberg’s biographer, Mario Kessler, also provided useful information. Relatives and friends of other people whom Harry knew in Berlin have also been generous with their knowledge. Dorothee Gottschalk–the widow of Lutz (Ludwig) Gottschalk, whom Harry had known in Berlin–contributed her knowledge of the Gottschalk family and some of their friends. Michael Freyhan contributed knowledge of the Freyhan family. David Sanford and Irene Hirschbach gave information on the Hirschbach family, and Irene sent two unpublished biographical essays by her late husband, Ernest Hirschbach. As time went on, I came to know (electronically) Peter-Thomas Walther of Humboldt University, Gottfried Niedhart of Mannheim University, and Daniel Becker, all of whom have shared their learning.

Other people have been generous in giving me information. Harry’s late cousins, Margaret Marks and Hannah Bildersee, sent me family history twenty-five years before I dreamed of this project. Cousins of my generation, Mary Misrahi Rancatore and Julienne Misrahi Barnett, supplied additional information. When I interviewed my mother’s oldest surviving sibling, Vida Castaline, in the mid-1970s, I had no idea that I would later rely on her remarkably detailed recall of life in Russia and, later, in Boston. Sidney Lipshires, who had been a Communist official in Massachusetts and, later, Harry’s doctoral student, knew valuable details about Harry’s Communist past. Curt Beck, whose long career at the University of Connecticut (UConn) overlapped Harry’s, offered additional information about the 1950s. Emanuel Margolis, a victim of McCarthyism at UConn, was kind enough to recall those painful days with a frankness that took my breath away. Bruce Stave, also of UConn, had just finished his excellent history of the university when I began my work and helpfully answered questions. Ellen Schrecker sent the spare but illuminating notes that she made when she interviewed Harry in 1979 for No Ivory Tower: McCarthyism and the Universities. Miriam Schneir gave invaluable advice at the end of the process and suggested the title. Lily Munford, Peter Schaefer, and Waltraut Engelberg helped transliterate the old German script in which most of Grete Meyer’s letters and some of the other Berlin letters were written, as well as short notes written in German by my maternal grandmother’s family. Lily, in addition to doing the lion’s share of transliteration, undertook the considerable task of translating the Meyer letters. At the very beginning, Ingrid Finnan translated three of Engelberg’s letters and insisted that I could do the other three, thus giving me an incentive to revive my college German; at the very end, she provided essential expertise in preparing the photographs for publication. Except for the Meyer letters and those that Ingrid translated, translations of letters from the Berlin friends are my own, as are any otherwise unascribed translations. Michiel Nijhoff helped with Dutch. Members of H-German, the HNet discussion group on German history, advised a trespasser in their realm.

.....

Sometimes Harry attended lectures in other fields. In his last semester, Hans Kauffmann’s lectures on Dutch painting in the seventeenth century fed his love of Rembrandt and Vermeer. Like most art historians in Harry’s view, Kauffmann was “a pleasant lecturer, slow and daintily speaking.” Harry’s initial praise of Kauffmann’s “penetrating” discourse gave way to complaints of seven weeks “wasted…on Rubens.” He enjoyed the lecture on Vermeer but wondered impatiently: “When is he coming to Rembrandt?” Finally Kauffmann delivered “a very fine lecture, full of understanding and feeling,” about Rembrandt as a painter of “the dialectic of life”: he painted the prodigal son when his own son died, and Bathsheba when his beloved Hendrikje Stoffels died. Harry was overcome with emotion by a slide of a self-portrait and another of Jacob blessing his grandchildren. He struggled to describe his feeling:

It is not that ecstasy I feel when I hear [Sigrid] Onegin’s voice–it may be what Spinoza meant with his intellectual love of god. It is less sensual, more appreciative than being dissolved into exquisite sensations by that heavenly voice. I love that man…. Learning to meet Rembrandt is maybe the most important result of these two years.

.....