Читать книгу Hero of the Angry Sky - David S. Ingalls - Страница 1

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

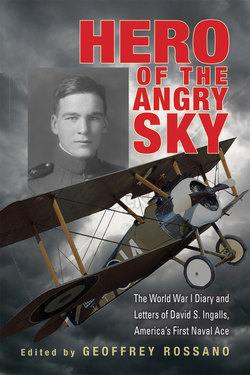

ОглавлениеHero of the Angry Sky

The World War I Diary and Letters of David S. Ingalls,

America’s First Naval Ace

Edited by Geoffrey L. Rossano

Foreword by William F. Trimble

Ohio University Press Athens

Contents

Contents v

Illustrations vii

Foreword xi

Series Editors’ Preface xiii

Acknowledgments xv

A Note on the Text xvii

Abbreviations xix

Introduction 1

Training with the First Yale Unit 21

Early Days in Europe 44

With the RFC at Gosport, Turnberry, and Ayr 88

On Patrol—At NAS Dunkirk and with the RAF in Flanders 143

The Navy’s Big Show—The Northern Bombing Group 185

Hero of the Angry Sky—Serving with 217

No.213 Squadron 217

Eastleigh and Home 288

A Glance Back 316

Afterword 330

Appendix 1 340

Appendix 2 342

Bibliography 366

Illustrations

Following page 32

Lt. David Ingalls

The First Yale Unit in Florida for training, spring 1917

F. Trubee Davison, founder of the First Yale Unit

Artemus “Di” Gates of the Yale Unit, with Curtiss F Boat

Members of the First Yale Unit relaxing in Florida 000

Di Gates’s Number 7 crew with Curtiss F Boat in Florida

Crew readying Curtiss F Boat training aircraft

Lt. Eddie McDonnell and Col. Lewis Thompson in Florida

The Yale Unit gathered for muster in Florida

The Yale Unit in Huntington, New York, June 1917

F Boats and a twin-float R-6 at Huntington Bay

Members of the Yale Unit hauling a Curtiss R-6 trainer/scout aircraft out of the water

Ensign Ingalls in his new uniform, early September 1917

The SS Philadelphia (former City of Paris)

Navy gun crews drilling aboard Philadelphia, summer 1917

Following page 134

Ingalls shortly after landing in England

U.S. Navy facility at Moutchic

FBA flying boat

Robert “Bob” Lovett of the First Yale Unit

Capt. Hutch I. Cone, director of naval aviation activities in Europe

Avro 504 trainer

Two Avro 504 trainers after a collision, winter 1917–18

Ken MacLeish

Sopwith Camel

Upended Camel after a training accident

Following page 178

Hand-drawn map of Dunkirk harbor by Lt. Kenneth Whiting

Lt. Godfrey Chevalier, CO at NAS Dunkirk

George Moseley

Yale Unit veteran Samuel Walker on a visit to Dunkirk, with Di Gates

Hanriot-Dupont scout being lowered into the water by derrick at Dunkirk

U.S. Navy station at Dunkirk after a German raid in late April 1918

Seawall at NAS Dunkirk with Hanriot-Dupont scouts

Ingalls, Ken MacLeish, and “Shorty” Smith at the Bergues aerodrome, April 1918

Following page 278

Ingalls with John T. “Skinny” Lawrence and acquaintance in Paris, May 1918

Breguet 14B.2 at Clermont-Ferrand

Observer/machine gunner Randall R. Browne of the First Aeronautic Detachment

DH9 day bomber

Aerial reconnaissance photograph of the dockyards and submarine pens at Bruges

Capt. David Hanrahan, Northern Bombing Group commander, with officers

Chateau at St. Inglevert, a point of rendezvous for members of the Yale Unit

Ingalls in Flanders, possibly during duty with Northern Bombing Group, July–August 1918

Ingalls with 213 Squadron mates, August 1918

Following page 308

U.S. Navy’s Flight Department at Eastleigh

Warrant Officers Einar “Dep” Boydler and William “Bill” Miller at Eastleigh

Warrant Officer William “Bill” Miller with Liberty motor–powered DH-9a day bomber

Randall Browne and crew members at Eastleigh

Ingalls with fellow officer at Eastleigh

Members of senior officer corps of Eastleigh at armistice

Ingalls with enlisted personnel of the Flight Department of Eastleigh at the end of the war

RMS Mauretania

Following page 334

Ingalls with Admiral H. V. Butler in San Diego, 1929

Foreword

Curiously, given the scale and drama of the U.S. Navy’s World War I aviation effort, there are no published biographies of navy combat aviators. Now, thanks to Geoffrey Rossano, a skilled and knowledgeable historian whose recent works include a comprehensive study of the navy’s air arm in Europe, we have a fine-grained, up close and personal glimpse into the wartime career of David Sinton Ingalls, as told in his own words. The navy’s first and only World War I “ace,” credited with six victories while attached to an RAF pursuit squadron, Ingalls was still a teenager when he dropped out of Yale and volunteered for aviation training and service as a naval reserve officer. Like many members of the famed First Yale Unit, Ingalls came from the country’s privileged elite, and like his comrades in arms, he dreamed of the excitement, honor, and glory that modern air warfare seemed to herald. Of course, as Ingalls himself related, the reality was often much different. He endured days and sometimes weeks of tedium on the ground, underwent seemingly endless training, and flew innumerable fruitless patrols over “Hunland” behind the front lines. What to the public appeared to be romantic, chivalrous aerial jousting was in fact a deadly industrial age war of attrition in which men and machines were consumed as appallingly as they were by the artillery and machine guns on the ground.

Using a veritable treasure trove of Ingalls’s letters and diaries, Rossano brings the air war to life with informative and unobtrusive editing skill. The result is that readers will have the rare opportunity to see World War I in the air firsthand. In Ingalls’s remarkably clear voice, we hear the range of emotions that often overwhelmed young men separated from their families and exposed to the dangers of flight and combat. We share Ingalls’s exhilaration in the sheer intoxicating sensation of flight and the satisfaction he experienced in successfully completing a mission. We see how he carefully worded his letters home to his mother and father to mask the dangers he faced. And we see how his nearly daily diary entries paint another, more realistic picture, vividly showing that sometimes only a combination of luck and skill kept him alive in the air and got him safely back to earth.

In this book, we meet some of the key players in early American naval aviation. Among them are Yale Unit chums F. Trubee Davison, Artemus “Di” Gates, and Robert “Bob” Lovett, all of whom went on to noteworthy careers in aviation and public service. A keen observer of the strengths and weaknesses of the navy’s effort in Europe, Ingalls had great respect for Ken Whiting and Hutch Cone, who oversaw the material and organizational aspects of the great enterprise. Like everyone else, Ingalls experienced loss in the merciless skies over France and Belgium. Gates went down and was held as a prisoner of war, and Kenneth MacLeish (brother of poet Archibald MacLeish) was killed only hours after joining the squadron when Ingalls, exhausted from combat, rotated back to England. Frederick Hough, Al Sturtevant, Curtis Read, Harry Velie, and Andrew Ortmeyer, to name only a few, had their lives cut short and will forever be reminders of the human cost of aerial warfare.

I feel certain that readers will agree with me that Rossano’s Hero of the Angry Sky provides a gripping first-person account that incorporates all of the tragedy, excitement, frustration, sacrifice, and ultimately human triumph that accompanied the navy’s Great War in the air.

William F. Trimble

Auburn University

Series Editors’ Preface

Wars have been the engines of North American history. They have shaped the United States and Canada, their governments, and their societies from the colonial era to the present. The volumes in our War and Society in North America book series investigate the effects of military conflict on the peoples in the United States and Canada. Other series are devoted to particular conflicts, types of conflicts, or periods of conflict; ours considers the history of North America over time through the lens of warfare and its effects on states, societies, and peoples. We conceive “war and society” broadly to include the military history of conflicts in or involving North America; responses to war, support as well as opposition opinion, peace movements, and pacifist attitudes; examinations of American citizens and Canadian citizens, colonists, settlers, and Native Americans fighting in or returning from wars; and studies of institutional, political, social, cultural, economic, or environmental factors specific to North America that affected wars. Our series explores the ties between regions and nations in times of extreme crisis. Ultimately, volumes in the War and Society in North America series should be a venue for authors of books that will appeal to a wide range of audiences in military history, social history, and national and transnational history.

In Hero of the Angry Sky, Geoffrey Rossano fulfills all the expectations for our series. He brings to light the experiences of one of America’s first flying aces, the naval aviator David Ingalls in the First World War. Ingalls, an Ohioan from Cleveland, shot down five German aircraft and became the only ace in the U.S. Navy during that conflict. Ingalls joined the preparedness movement in 1916 as an undergraduate student at Yale University and he went on to volunteer service in the war. This book is not merely a combat narrative, however, because Rossano effectively blends Ingalls’s diary entries and personal letters in a whole-life story with fascinating material on flight training, aviation technology, and even France’s wartime society. His book also serves to commemorate the early years of naval aviation and the upcoming one-hundredth anniversary of the formation of the First Yale Unit of volunteers for the Great War. After the war ended, Ingalls went on to careers in law, business, Ohio politics, and national politics. As an assistant secretary of the navy in President Herbert Hoover’s administration, Ingalls directed the expansion of naval aviation and the development of aircraft carrier–based air power that would bear fruit in the Second World War. There can be no doubt that Ingalls’s own experiences as an aviator in the Great War left lasting impressions on him and made him a strong advocate for naval air power for the rest of this life.

We are proud to have Geoffrey Rossano’s Hero of the Angry Sky as the inaugural volume in the series War and Society in North America. Throughout the review and editing phases, Rossano has been the consummate scholar. We could not have asked for a better author and partner in publishing. We would be remiss if we did not also thank Gillian Berchowitz, the editorial director at Ohio University Press. Gillian has been very supportive throughout the process of creating our series and in working with Geoffrey Rossano on Hero of the Angry Sky.

David J. Ulbrich

St. Robert, Missouri

Ingo Trauschweizer

Athens, Ohio

Acknowledgments

To edit someone’s private diary and correspondence is, in a way, to become part of that person’s life, family, and social circle and share his or her time and place, no matter how far removed. Working with David Ingalls’s papers was just such an experience. During many months poring over his writings, deciphering his tight penmanship, “meeting” his friends and acquaintances, and listening in on his thoughts, I came to know the teenage man-boy who became naval aviation’s first ace. Visiting several of the places where he trained and served, literally following in his footsteps, provided additional insight. It has been a fascinating and rewarding journey.

My greatest thanks go to members of the extended Ingalls family for making David Ingalls’s papers available to me and supporting this project right from the beginning. They opened both their homes and their archives. Especially helpful have been Jane Ingalls Davison, David Ingalls’s daughter; Dr. Bobbie Brown, his granddaughter; and Polly Hitchcock, his great-granddaughter. I would also like to thank the staff at the Louise H. and David S. Ingalls Foundation, particularly Jay Remec. All were enthusiastic about the project from start to finish.

A great variety of individuals, organizations, and repositories made completion of this work possible. The National Archives in Washington remains the central repository for documents relating to early things naval. The large and varied resources of the Naval History and Heritage Command located at the Washington Navy Yard proved very helpful, as did the staff in the library, the Photo Section, and especially the naval aviation unit of the archives, particularly Joe Gordon and Laura Waayers. The Naval Institute library in Annapolis provided access to many scarce books and publications, as did the Emil Buehler Library at the Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. Jack Fine at the Buehler Library greatly assisted in the search for photographs. Archivist David Levesque at St. Paul’s School helped identify many of David Ingalls’s school friends and associates, and Roger Sheely generously provided access to his own father’s World War I papers and photograph albums, which contained much material relating to Ingalls’s involvement with the Northern Bombing Group program. Peter Mersky also permitted reproduction of several photographs from his collection. I have also enjoyed working with Darroch Greer and Ron King, producers of the outstanding documentary film The Millionaire’s Unit: America’s Pioneer Pilots of the Great War. They provided several leads and insights into the world of the First Yale Unit.

Finally, my hearty thanks go to the editors and professionals at Ohio University Press who made the task of completing this project a pleasure rather than a burden. These include series editors Ingo Trauschweizer and David Ulbrich and Editorial Director Gillian Berchowitz.

Geoffrey L. Rossano

A Note on the Text

Principal Sources:

Diary, two volumes, September 1917–November 1918

Letters to parents and others, April 1917–November 1918

Typescript diary/memoir prepared in the early postwar period

Observations/Analysis re: training at Turnberry and Ayr

Informal logbook entries scattered through the diary

Technical notebook re: gunnery, equipment lectures at Turnberry

RAF squadron reports

This book incorporates the complete chronological text of David Ingalls’s extant World War I letters and diary, technical notes from his time at Turnberry, an analysis of training at Ayr and Turnberry, random flight records, and official RAF squadron reports/flight reports, supplemented where appropriate by material drawn from his postwar (c. 1924) personal memoir. Also included is the transcript of after dinner remarks made at a 1924 reunion of the Yale fliers. Obvious misspellings have been corrected. In the few instances where Ingalls’s handwriting made deciphering a word or phrase problematic or where words have been inserted to provide clarity, the editor has so indicated with brackets—[ ]—in the text.

Chapter organization reflects discrete periods in Ingalls’s wartime instruction and service, beginning with chapter 1, his early training in Florida and New York. Chapter 2 covers his voyage across the Atlantic and early months in England and France. Chapter 3 includes material related to training with the Royal Flying Corps from December 1917 until March 1918. Chapter 4 documents Ingalls’s service at NAS Dunkirk and with No.213 Squadron, RAF, in the period March–May 1918. Chapter 5 is devoted to his months of training for duty with the Northern Bombing Group and service with an RAF bombing squadron. Chapter 6 covers his time at the front with No.213 Squadron in August–October 1918, the months when he scored all of his aerial victories. Chapter 7 describes Ingalls’s final wartime duties at the navy’s assembly and repair facility at Eastleigh, England, and his trip home.

The volume incorporates both editorial comments and annotations. The editorial material is designed to place Ingalls’s words and actions into historical context, while offering a succinct narrative of his life and the events of his military career. Most of this information is located at the beginning of chapters or in extended footnotes. The objective is not to retell the entire story of naval aviation in this period. Rather, every attempt has been made to give substance to Ingalls’s own voice, to let one young man tell his own story, completely, for the very first time.

Finally, the annotations. Throughout his surviving letters, diary, and other documents, David Ingalls mentioned a vast cast of characters, organizations, places, and events. A few are well known to the casual reader, but most are not, even to those well versed in the history of the period. Many references, at a distance of nearly a century, are quite obscure. To address this issue and help the reader understand the flow of events but not overwhelm Ingalls’s narrative, the editor has indicated the terms, characters, places, and other material to be identified with a footnote number, with the actual identification/explanation placed at the bottom of the page.

Abbreviations

AA antiaircraft

A & R assembly and repair

AEF American Expeditionary Force

BM Boatswain’s Mate

CNO Chief of Naval Operations

CO commanding officer

C.P.S. Carson, Pirie, Scott

DFC Distinguished Flying Cross

DSC Distinguished Service Cross

DSI David Sinton Ingalls

DSM Distinguished Service Medal

DSO Distinguished Service Order

EA enemy aircraft

FAD First Aeronautic Detachment

GM Gunner’s Mate

HOP high offensive patrol

j.g. junior grade

MG machine gun

MM Machinist Mate

NA Naval Aviator

NAS Naval Air Station

NBG Northern Bombing Group

NRFC Naval Reserve Flying Corps

QM Quartermaster

RAF Royal Air Force

RFC Royal Flying Corps

RNAS Royal Naval Air Service; Royal Naval Air Station

VC Victoria Cross

Introduction

In 1925, Rear Admiral William S. Sims, commander of U.S. naval forces operating in Europe during World War I, declared, “Lieutenant David S. Ingalls may rightly be called the ‘Naval Ace’ of the war.”1 Of the twenty thousand pilots, observers, ground officers, mechanics, and construction workers who served overseas in the conflict, only Ingalls earned that unofficial yet esteemed status. In contrast, by November 1918, the U.S. Army Air Service counted more than 120 aces.2

The Cleveland, Ohio, native’s unique achievement resulted from several factors. Unlike their army peers, few naval pilots engaged in air-to-air combat. Instead, most patrolled uncontested waters in search of submarines. A bare handful served with Allied squadrons along the Western Front, the true cauldron of the air war. By contrast, David Ingalls spent much of his flying career stationed at NAS Dunkirk, the navy’s embattled base situated just behind enemy lines, or carrying out missions with Royal Air Force (RAF) fighting and bombing squadrons. He did three tours with the British, all without a parachute or other safety gear, and he hungered for more. The young aviator managed to be in the right place at the right time, and as was true for nearly all surviving aces, luck smiled on him.

David Ingalls’s personal attributes played a crucial role in his success. A gifted athlete, he possessed extraordinary eyesight, hand-eye coordination, strength, agility, and endurance. An instinctive, confident flier, Ingalls learned quickly and loved the aerial environment. With a head for detail, he easily mastered the many technical facets of his craft. He was also an excellent shot and unforgiving hunter. Finally, Ingalls possessed the heart of a youthful daredevil, a hell-raiser who gloried in the excitement and challenge of aerial combat. He seemed fearless and quickly put one day’s activities behind him even as he prepared for the next mission. He went to war a schoolboy athlete and came home a national hero. And he was still only nineteen years old when the guns fell silent.

Although Ingalls’s wartime experiences are compelling at a personal level, they also illuminate the larger but still relatively unexplored realm of early U.S. naval aviation. According to military historians R. D. Layman and John Abbatiello, naval aviation carried out a wide variety of missions in World War I and exercised far greater influence on the conduct of military affairs than heretofore acknowledged. Aircraft protected convoys from attack and played an increasingly vital role in the campaign against the U-boat. Aviators aided the efforts of naval units and ground troops in military theaters extending from the North Sea and English Channel to Flanders, Italy, Greece, Turkey, and Iraq. Fleet commands, most notably in Great Britain, worked to integrate the new technology into ongoing operations and develop innovative applications.3

As the United States developed its own aviation priorities, missions, and doctrines during 1917 and 1918, it aspired to similar success. Despite his extreme youth, David Ingalls was repeatedly selected by the navy to play a pathbreaking role in this process. He began as one of the very first pilots dispatched to Europe for active duty “over there.” Once ashore, he became one of only three aviators chosen to receive advanced training at Britain’s School of Special Flying at Gosport, preparatory to assuming the role of flight commander at beleaguered NAS Dunkirk. During the terrifying German advance of March–April 1918, he and three other American pilots joined a Royal Air Force fighting squadron operating over Flanders. Later that year, he became one of the initial members of the navy’s most significant offensive program of the entire war, the Northern Bombing Group (NBG), and then flew several bombing missions with the RAF. After just a few weeks’ ground duty with the NBG, Ingalls returned to British service for two months, becoming the only navy pilot to fly over the front lines for such an extended period. While with the RAF, he served as acting flight commander ahead of many longtime members of his squadron. In recognition of this work, he became the first American naval aviator to receive Britain’s Distinguished Flying Cross. He finished his service as chief flight officer at the navy’s sprawling assembly and repair depot at Eastleigh, England.

Ingalls’s wartime correspondence offers a rare personal view of the evolution of naval aviation during the war, both at home and abroad. There are no published biographies of navy combat fliers from this period, and just a handful of diaries and letters are in print, the last appearing in the early 1990s.4 Ingalls kept a detailed record of his wartime service in several forms, and his extensive and enthusiastic letters and diaries add significantly to historians’ store of available material. Shortly after enlisting in the navy in March 1917, he began corresponding with his parents in Cleveland, Ohio, a practice he continued until late November 1918. Someone in his father’s offices at the New York Central Railroad transcribed the handwritten letters and pasted them into a scrapbook containing materials documenting his military career.5

Ingalls’s letters reveal a lighthearted and affectionate relationship with his parents, and they are often filled with valuable insights into the tasks he performed, though he shielded his folks from the true dangers he faced. He limned his most hair-raising experiences with the glow of a sportswriter discussing a star athlete’s exploits. Though the letters contain much information about his social life in Europe, the teenage flier did not tell his mother about the “short arm” inspections he performed on enlisted men, searching for signs of venereal disease.

Upon sailing to Europe in September 1917, the recently commissioned junior officer commenced keeping a detailed diary, eventually filling two compact notebooks. Ingalls also compiled an informal record of his flight activities by jotting down spare notations throughout his diary, listing hours and types of aircraft flown. Surprisingly, no official logbook survives. These daily entries have a very different texture from that of his letters, being more matter-of-fact and more cryptic yet still recording the major and lesser activities that structured his days and the days of those around him. He expressed frustration with endless training, occasional boredom, dislike of army fliers, and hints of fear and nerves, an altogether less sugarcoated version of reality. While training in Scotland, the neophyte aviator transcribed lengthy notes during various lectures and from technical publications. He also produced a formal analysis of instruction at Ayr and Turnberry. Both are reproduced here.

Shortly after the war but likely no later than 1924, a more mature Ingalls prepared a hundred-page typescript memoir, incorporating much of the language of his diary and letters verbatim, interspersed with material reporting additional events, descriptions drawn from memory where no letters or diary entries survived, or editorial comments about his experiences. The memoir offers yet another interpretation of Ingalls’s activities, the tone by turns analytical and dramatic, with something of the flavor of a pulp novel. Wartime terror and boredom are gone, replaced by the occasional smirk or wink. His descriptions of social life and visits to nightclubs seem wiser, more knowing, as he speaks with the voice of a grown man recounting the escapades of a teenage boy.

Despite his officer status, Ingalls provided a distinctly civilian view of military life in his writings, albeit a rather privileged version of that existence. For him, this was all a great adventure, not a career. The navy’s decision to keep its regular young officers with the fleet and not train any as aviators meant volunteer reservists such as Ingalls filled the ranks of combat units.6 And like him, many came from affluent, socially prominent families. The young Ohioan thus had much to say about the social scene in London and Paris, and his experiences differed greatly from the hardships suffered by enlisted bluejackets at sea or doughboy infantrymen in the mud and trenches.

Ingalls’s story also, in the words of author Henry Berry in Make the Kaiser Dance, partakes of the persistent aura of glamour attached to the young Americans who flew their fragile, dangerous machines above the Western Front. Anyone who has ever raced across the sky in an open-cockpit biplane knows something of that feeling. Of Ingalls and his peers, Berry remarked, “Their names seem to conjure up the list of the romantic aspects of war—if shooting down another plane in flames, or suffering the same fate, is glamorous.” In a world of mud, horror, anonymity, and mass death, they became celebrities. The less-than-unbiased Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell proclaimed, “The only interest and romance in this war was in the air,” and historian Edward Coffman observed, “No other aspect of World War I so captured the public imagination.”7

Concerning his aviation duties, Ingalls offered insight into the lengthy, varied, sometimes contradictory, and often ad hoc instruction received by the first wave of navy fliers preparing for wartime service. He bemoaned the fact that training never seemed to end. Reassignment from flying boat–patrol training, to land-based combat instruction, to seaplane escort duty, and to cross-lines bombing raids, followed by more escort duty, then training in large bombers, and finally assignment to a British combat squadron reflected the navy’s continually shifting plans and priorities. The fleet entered the war with no aviation doctrine, precious few men, and little matériel, and it took many months to get the program headed on a winning course. As Capt. Thomas Craven, commander of naval aviation in France in the final months of the conflict, noted, his bases and squadrons, like John Paul Jones, “had not yet begun to fight,” even as Germany prepared to surrender.8

Among the first collegiate fliers to jump into the game, David Ingalls began training even before Congress declared war. In the months that followed, he mastered command of flying boats, seaplanes, pursuit aircraft, and bombers, more than a dozen machines in all. Ingalls’s work took him from Florida to New York and then to England, Scotland, and France. He became a trailblazer for the many that followed, and his duties included antisubmarine patrols, bombing raids, test flights, at-sea rescues, dogfights, and low-level strafing attacks. In all his assignments, he displayed intelligence, exuberance, and technical skill. His superiors entrusted him with significant responsibility, and he more than fulfilled their expectations. Ingalls achieved great success in all his endeavors and despite his youth earned the praise, admiration, and respect of those around him. His experiences mirrored the course of the navy’s first venture into the crucible of aerial combat. David Ingalls’s story is naval aviation’s story.

By any reckoning, David Sinton Ingalls of Cleveland, Ohio, lived an extraordinary life. Long before he flew into aviation history, he seemed destined for high achievement. It was in his blood. Born into an affluent, socially and politically prominent midwestern family, he enjoyed great success as a youthful athlete. His exploits in World War I made him a national hero. The postwar era brought further accomplishments—degrees from Yale and Harvard; marriage to an heiress and a busy family life; a high-profile career in politics, law, business, and publishing; a busy and productive stint as undersecretary of the navy for aeronautics in the Hoover administration; distinguished military service in World War II; extensive activity as a sportsman and philanthropist; and a lifelong commitment to his passion for flying as both a pilot and an aviation enthusiast. And whatever activity he pursued, he did so with energy and zest.

David Ingalls’s family tree incorporated some of Ohio’s most prominent citizens. On his mother’s side, he descended from David Sinton (1808–1900), whose parents arrived from Ireland and settled in Pittsburgh. Described much later as a man of “irregular education,” Sinton was known as “a large, strong person with strong common sense.”9 He eventually relocated to southern Ohio, made a fortune in the iron business, and was at one time perhaps the richest man in the state. His elegant, Federal-style Cincinnati home survives today as the Taft Museum of Art. Sinton’s only daughter, Anne (1850–1931), inherited $20 million from her father. She married Charles Phelps Taft (1843–1929), son of Alphonso Taft (1810–91), a man of solid Yankee stock. Originally from West Townshend, Vermont, the elder Taft graduated from Yale (Phi Beta Kappa) and Yale Law School and by 1859 had settled in Cincinnati, where he attained legal and political prominence. He ultimately served as U.S. secretary of war and attorney general and later ambassador to Austria-Hungary and Russia.

Alphonso Taft’s son Charles, the older half brother of William Howard Taft (the future judge, secretary of war, president, and Chief Justice of the United States), became a prominent lawyer in his own right, as well as a congressman and publisher of the Cincinnati Times-Star. According to Robert A. Taft’s biographer, “Wealthy brother Charley” often provided financial assistance to his justice sibling, while emerging as one of Cincinnati’s leading philanthropists. Charles and Anne Taft lived in David Sinton’s mansion until the late 1920s. Their only daughter, Jane Taft (1874–1962), was David Ingalls’s mother. She exhibited a lifelong interest in the arts and became a patroness of many museums and organizations. She also earned a local reputation as a talented painter and sculptress.10

Paternal grandfather Melville Ingalls (1842–1914), another Yankee, hailed from Maine and moved to Massachusetts, where he gained distinction as a lawyer and politician. After relocating to Cincinnati, he fashioned a remarkable career in railroads and finance. In time, he became president of several rail lines, including the Indianapolis, Cincinnati & Lafayette, later part of the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago, & St. Louis, known as the Big Four Railroad. Melville Ingalls also controlled the Merchants National Bank, the city’s second-largest financial institution. His “imposing estate” stood in Cincinnati’s fashionable East Walnut Hills neighborhood. Melville’s son, Albert S. Ingalls (1874–1943), achieved great success as well, Born in Cincinnati, he attended St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire and Harvard, then went to work for his father’s railroad, starting out dressed in overalls rather than a business suit. He worked his way up through the system at the Big Four, then Lake Shore Railroad, and finally New York Central Railroad, where he became vice president and general manager of operations west of Buffalo, New York. As his career blossomed, Albert Ingalls moved to Cleveland, earning some notoriety as the second man in the city to own an automobile. He was long remembered as a hard worker and quick thinker, a master of English who could clear a desk of correspondence in record time. He exhibited a democratic spirit and genial personality and an admirable mixture of culture, quick-wittedness, broad interests, and robust energy. From an early age, Albert Ingalls enjoyed smoking a clay pipe. Many of his personal traits he passed on to his children, especially David.

Albert Ingalls and Jane Taft married in Cincinnati, linking two important Ohio clans, but soon relocated to Cleveland. The young couple lived first in the city, then in Cleveland Heights. They had three children—David, Anne, and Albert. David, the eldest, was born on January 28, 1899. In 1906, the family moved to Bratenahl, one of the city’s early elite residential suburbs on the shores of Lake Erie, known for its prominent families and manicured estates. Residents included members of the region’s financial and industrial elite, including the Hannas, Irelands, Chisholms, Holdens, Kings, McMurrays, and Pickandses. David Ingalls’s lifelong friend and fellow naval aviator, Robert Livingston “Pat” Ireland, lived nearby. Ingalls spent summers at the lakeshore or visiting his many relatives, especially his Taft cousins.

His academic training included time spent at University School in Cleveland, an independent day school founded in 1890. In 1912, Ingalls entered St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire, from which he graduated in 1916, having participated in the requisite campus organizations, including the mandolin club, literary society, and scientific association. He played football and tennis and was twice schoolwide squash champion. Ingalls’s most notable exploits came on the ice as a standout hockey player. Some even compared him to the nonpareil athlete Hobey Baker, who preceded him by a few years. At the time, the school was “ardently Anglophile . . . High Church,” and it drew much of its student body from the New York–Philadelphia Main Line. While at St. Paul’s, Ingalls came under the stern influence of Rector Samuel Drury, a former missionary to the Philippines who worked diligently to improve the school’s commitment to ethical and academic standards. Drury often told his charges, “From those to whom much is given, much is expected.”11

Ingalls’s schoolboy years, whether at St. Paul’s or at home in Cleveland, exposed him daily to the controversies ignited by the terrible war that broke out in Europe in 1914 and America’s appropriate response to it. As the history of St. Paul’s School documents, there was considerable anti-German feeling at that time, and both students and faculty quickly forged many connections to the fighting. Several masters attended summer military camps. Graduates enlisted with the French or British forces. Students marched in preparedness parades, volunteered for military drill, and carried out raids on various campus buildings.12 Like the strong winds blowing off Lake Erie, news of the war and the fierce debate it generated also buffeted Cleveland, a flourishing city with a yeasty mix of rich and poor, native and immigrant, liberal and conservative. News of the sinking of the Lusitania in early May 1915 covered every inch of the front page of the Cleveland Plain Dealer. When the German consul in Cincinnati released a statement in January 1916 defending his country’s actions in the war, the story received wide circulation throughout the state. That same day, notices informed Clevelanders that new war motion pictures were playing in local theaters.

Residents read about vigorous efforts by pacifist, preparedness, and interventionist groups to sway public opinion. In 1915, Mayor Newton Baker, known for his antimilitarist stance, joined social reformer Jane Addams in praising the antiwar film Lay Down Your Arms. In the same year, Cleveland Women for Peace held a tea to honor delegates to the World Court Congress. Mrs. Baker, the mayor’s spouse, presided at the event. The miners’ union came out against military preparedness in January 1916, and members of the Cleveland Young People’s Socialist League celebrated an antiwar day the following September. In November 1916, Cleveland and surrounding Cuyahoga County voted for President Woodrow Wilson (“He kept us out of war”) by a 52-to-44 percent margin. This result received the approbation of the November 9 Plain Dealer editorial page, which praised Wilson for “his sane Americanism, opposition to war-at-any-price jingoes, and professional hyphenates.”

Cleveland supporters of preparedness and the Allies, however, were also vocal and well represented throughout the prewar period. Many of the city’s Yale graduates urged visiting university president Arthur Hadley to support military preparedness. In July 1915, prominent citizens organized a local chapter of the National Security League and campaigned actively for the next two years. The following summer, Bascom Little, an influential local businessman and philanthropist and member of the National Defense Committee of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, traveled to Washington, D.C., to urge Congress to pass a proposed universal military training bill. Everyone, it seems, had an opinion about the war and what the United States should do about it.13

In the fall of 1916, David Ingalls entered Yale University to pursue medical studies, and he again distinguished himself on the ice as captain of the freshman hockey team. Great-uncle William Howard Taft, former president and now member of the law school faculty, lived just a few blocks away. Somewhere along the way, likely at St. Paul’s or in that first year at Yale, Ingalls acquired the nickname “Crock,” derivation uncertain. (Daughter Jane Ingalls Davison later insisted no one in Cleveland ever called him by that name.) Ingalls soon became close friends with Henry “Harry” Pomeroy Davison Jr., son of J. P. Morgan partner Henry Pomeroy Davison and younger brother of F. Trubee Davison.14 While Ingalls was in New Haven, his childhood fascination with flight, his innate joy in reckless physical action, his social connections to influential fellow students, and the prewar preparedness frenzy sweeping eastern colleges almost inevitably turned his attention toward an aviation unit being formed by Trubee Davison.

By late 1916, concern over events in Europe, where the Great War staggered through its third year, and the debate regarding America’s role in the struggle reached a fever pitch, dominating the national conversation. When war had broken out in the summer of 1914, reaction had been mixed. President Wilson, who “resolutely opposed unjustified war,”15 insisted the United States remain neutral in the struggle and actively resisted planning for possible military intervention. Military historian Harvey DeWeerd observed, “The war was nearly two years old before Wilson allowed government officials to act as if it might sometime involve America.” Newton Baker, now secretary of war, had been a spokesman for the League to Enforce Peace. Editor George B. M. Harvey of Harper’s Weekly responded by calling Baker “a chattering ex-pacifist.” Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, a man of pacifist and isolationist proclivities, proved equally critical of professional soldiers and sailors and general staffs.16

Many citizens concurred. Irish Americans opposed any aid for Britain. German Americans, including thousands in Ohio, tended to support their homeland. Antiwar sentiment ran strongly among reformers, women’s organizations, and church groups. The country’s large socialist movement called the conflict a capitalist conspiracy to generate profits and consume manpower. Traditionally isolationist regions of the United States strongly opposed involvement. Henry Ford chartered a “peace ship” to bring antiwar activists to an international conference held in Stockholm, Sweden in 1916. Reflecting the horrors unfolding on the Western Front, “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier” reigned as one of the most popular songs of 1915–16.17

Such feelings were not universal, however. In fact, though most Americans supported neutrality and narrowly reelected Woodrow Wilson on the belief that “he kept us out of war,” they still preferred a Franco-British victory to a German triumph. DeWeerd claimed, “The country was pro-Ally and anti-German from the start.”18 Fervent supporters of Great Britain and France saw the war as a struggle between democracy and Western civilization, on the one hand, and “Kaiserism” and the brutality of the “Huns,” on the other. Submarine attacks on civilian passenger liners such as the Lusitania almost caused a diplomatic rupture between the United States and Germany. The British blockade, protested only mildly by the Wilson government, diverted most trade to England and Western Europe, and a growing tide of orders for war materials engendered further support for the Allies. So did the ever-increasing flow of loans from major American investment banks such as J. P. Morgan.

Whether favoring or opposing active participation in Europe’s seemingly endless war, many citizens demanded their government prepare for possible involvement in the struggle, if only to defend national interests and American soil in case of a German victory. As David Kennedy noted, the outbreak of war “summoned into being . . . a sizable array of preparedness lobbies.”19 Some called for universal military training (conscription) and expansion of both the army and the navy. Former army chief of staff Leonard Wood, ex-president Theodore Roosevelt, and previous secretaries of war Elihu Root and Henry Stimson were only the most prominent among thousands of citizens who campaigned for such action. Leading bankers, industrialists, lawyers, academics, and politicians advocated a strongly Anglophile diplomatic and military policy, and a great mosaic of organizations took up the call.20

Citizen training camps conducted at Plattsburgh, New York, and elsewhere reflected the growing clamor for preparedness. College students and faculty members, recent graduates, young businessmen, and teaching masters from a score of eastern preparatory schools spent their summers drilling, camping, and learning to fire weapons. Another outgrowth of the preparedness movement, the National Defense Act of 1916, doubled the size of the army (to 240,000) and authorized a tremendous expansion of the battle fleet, though none of its provisions would be fully implemented for several years and thus would have little impact on the current crisis in Europe.21

Whatever their individual motivations, many young Americans, both men and women, took dramatic action to support the Allies. Thousands journeyed to Europe to drive ambulances, serve with the Red Cross, or perform varied volunteer duties. Others enlisted in the French Foreign Legion and eventually transferred to the aviation forces, forming what ultimately became the Lafayette Flying Corps. Still more traveled to Canada to join the British army or the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). Students at colleges such as Harvard, Princeton, and Yale formed quasi-military units and flying clubs, preparing for the day Uncle Sam might call on them.22

Even before Ingalls arrived in New Haven in September 1916, talk of war and preparedness monopolized much of the academic community’s attention, with the discussion by no means one-sided. Author George Pierson noted, “Yale was far from rising as one man to the support of Belgium and the Triple Entente.” Even as former president Taft called for strict neutrality, scholar George Adams declaimed, “Germany must be defeated in this war.” Initially, though very few students or faculty members favored the Central powers, equally small numbers advocated direct American involvement. Nonetheless, relief efforts to aid the Allies commenced almost immediately, and by 1915, many graduates called on the university to be more active in preparing for possible American involvement. Significantly, Yale president Arthur Hadley seemed “enthralled and excited by the preparedness movement,” and he praised military training for students.23

As early as April 1915, Hadley called for national preparedness, and later that year, he declared military training should have a place on college campuses. Addressing Yale alumni in Cleveland, he argued that the best way to keep the peace was to prepare for war. After visiting Plattsburgh in August 1915 and speaking with General Wood, Hadley in the fall announced plans to establish a field artillery battery on campus, and more than 1,000 undergraduates rushed to volunteer for the 486 available places. The faculty eventually voted to establish a Reserve Officers’ Training Corps unit, a proposal backed overwhelmingly (1,112 to 288) by the student body. The National Security League sponsored mass demonstrations, and preparedness and interventionist speakers including Henry Stimson and Adm. Bradley Fiske addressed undergraduates. In the winter of 1916–17, after years of urging neutrality, William Howard Taft admitted that war could no longer be avoided.

It was in this environment that two dozen Yale students and recent alumni coalesced in 1916–17 to create an aerial defense squadron. The First Yale Unit began as the brainchild of F. Trubee Davison. After his freshman year at college, Davison spent the summer of 1915 in war-torn Paris driving an ambulance. During those months, he met many prominent participants in the effort, including several combat fliers. He first envisioned organizing a volunteer ambulance unit at Yale but later determined to establish an aviation detachment instead. This concept dovetailed with contemporary proposals by John Hayes Hammond Jr., of the Aero Club of America, and Rear Admiral Robert Peary to create a series of aerial coastal patrol groups to protect American shores in case of war.24

By the spring of 1916, Davison had enlisted the support of several young comrades, including Harry Davison, Robert Lovett, Artemus “Di” Gates, Erl Gould, and John Vorys. Riding the wave of preparedness enthusiasm, he also gained the backing of influential private benefactors. Davison approached the Navy Department concerning his scheme and received modest encouragement, though no official support. Nonetheless, in July 1916, the fledgling group commenced training at aviation enthusiast Rodman Wanamaker’s Trans-Oceanic seaplane facility at Port Washington, New York, under the tutelage of pioneer flier David McCulloch.25 Of the dozen college boys who trained that summer, three soloed. Some of them also participated in naval reserve exercises.

Encouraged by the group’s successes, Davison and his mates increased their efforts to gain additional recruits after classes resumed at Yale—among them David Ingalls, just arrived in New Haven and still only seventeen—while intensifying discussions with the navy. In late winter 1917, when entry into the European war seemed inevitable, members of the group, now grown to more than two dozen volunteers, made plans to leave school and enlist. They did so with the support of President Hadley and Dean of Students Frederick Jones. On March 24, 1917, the Yale fliers traveled to New London, Connecticut, to complete the process. A few days later, they boarded a train to Palm Beach, Florida, to initiate instruction.

Commencement of unrestricted submarine warfare the previous winter had pushed the reluctant administration past the breaking point, and even as Ingalls and the rest of the Yalies begin training in Florida, President Wilson addressed Congress, asking for a declaration of war against Germany. The navy and its infant aviation arm would soon be called upon to do their part to defeat the U-boat scourge. The need was huge, the dangers great, and the threat mortal. In the first half of 1917, shipping losses to enemy submarines surged to intolerable levels, reaching nearly nine hundred thousand tons in April. Continued losses of that magnitude would quickly bring Britain to its knees. But in the opening days of hostilities, American naval aviation could not challenge the U-boat. Total flying resources consisted of a few dozen obsolete and obsolescent training aircraft; a lone underpowered, overweight dirigible; two balloons; a single understaffed and underfunded training facility at Pensacola, Florida; two score fliers (but none who had seen combat); and a few hundred enlisted ratings. The navy possessed neither aviation doctrine nor plans. No blueprints for wartime expansion existed, either for personnel or equipment.

Although the navy made modest technical progress in the years after the first fragile airplane took off from an anchored warship in 1910, it still lagged woefully behind the European combatants. In 1916, its three lonely assistant naval attachés posted to Berlin, Paris, and London supplied limited, circumscribed information about conditions in the war zone. A single lieutenant in the offices of the Aid for Material on the staff of the Chief of Naval Operations handled aviation affairs in Washington. A simple description of naval aviation activities in Europe reflects the degree to which the navy fell behind its future allies and enemies.26

By the spring of 1917, Britain’s Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) operated a growing number of coastal bases stretching from Scotland to the south coast of England and Dunkirk in France, and in April 1917, it initiated the “spider web” antisubmarine patrols over the North Sea. The Royal Navy’s air arm also employed several land-based squadrons on the Western Front, carrying out patrol, reconnaissance, and bombing missions; its aircraft inventory included modern Sopwith Camels and Triplanes, Handley Page heavy bombers, and huge Curtiss-derived Felixstowe flying boats. The RNAS also possessed a large fleet of SS-type airships, along with a well-developed network of training facilities. Kite balloons operated regularly with the fleet. Naval aviators carried out combat missions in the Aegean Sea, at the Dardanelles, and in Egypt, East Africa, and elsewhere. The RNAS had mounted bombing raids against German airship facilities at Friedrichshafen, Cologne, Dusseldorf, and Cuxhaven and against munitions and industrial targets, as well as airborne torpedo attacks at Gallipoli. Britain led the way in marrying aircraft to the fleet, deploying more than a dozen balloon ships, seaplane carriers, and prototype-hybrid aircraft carriers. One of these warships, Engadine, played a small role at the battle of Jutland. More sophisticated vessels were on the way. Other innovations included aircraft with folding wings, designed for easy, onboard stowage; internal air bags to keep downed machines afloat; and use of scout planes aboard battleships and cruisers by means of turret-mounted launching platforms.

Though the RNAS developed the biggest forces, other nations followed suit. Germany built the largest fleet of rigid airships (zeppelins), which conducted extensive scouting/reconnaissance missions for the High Seas Fleet and launched heavy bombing raids against London and other British sites. Germany also constructed numerous seaplane bases on home soil, along the Baltic coast, and in Belgium, and from these locations, it operated the world’s most sophisticated floatplane fighters. In April 1917, German naval air forces initiated a series of torpedo attacks against Allied shipping in the Dover Straits. France constructed a string of antisubmarine patrol stations to guard the English Channel, Bay of Biscay, and Mediterranean Sea, and its naval forces employed kite balloons during convoying operations. Italy developed the speedy, highly maneuverable Macchi flying boat fighters, based on an Austro-Hungarian prototype, and conducted a back-and-forth struggle across the narrow reaches of the Adriatic Sea. In 1916, Austro-Hungarian seaplanes sank a British submarine moored in Venice and shortly thereafter fatally damaged a French submarine at sea. As early as 1915, Russian naval forces in the Black Sea labored, with some success, to sever Turkish sea-lanes, utilizing up to three seaplane carriers.

It was in the shadow of these developments that the United States entered the fray in April 1917. Under forced draft, naval aviation eventually amassed forty thousand officers and enlisted men, augmented by thousands of aircraft and dozens of bases, schools, and supply facilities in Europe and the United States. By autumn 1918, navy fliers were ready to make substantial contributions to the war effort, but the armistice intervened. In the short run, however, before such a force could be assembled and deployed, the country necessarily relied on the efforts of individuals such as David Ingalls and hastily organized groups such as the First Yale Unit to carry out its evolving aeronautical campaign.

1

Training with the First Yale Unit

March–September 1917

David Ingalls spent his initial months in the navy training with the First Yale Unit in Florida and on Long Island, New York, a process directed by Lt. Edward McDonnell, a 1912 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy (USNA), where he became a champion boxer. McDonnell served at Vera Cruz, Mexico, in 1914 and received the Medal of Honor for heroism under fire. He began flight instruction at Pensacola a few months later and earned his designation as “Naval Aviator #18” (NA #18) in September 1915. In the spring of 1917, the navy ordered him to Palm Beach to direct training of the newly enrolled Yale fliers, assisted by civilians David McCulloch and Caleb Bragg, a small crew of petty officers and mechanics, and an assortment of civilian aides and staff. At the time, the college boys occupied Rodman Wanamaker’s southern Trans-Oceanic facilities on Lake Worth and boarded at the Hotel Salt Air in West Palm Beach.27

Work for the Yalies began immediately upon arrival, with the site and aircraft guarded by local militia. Divided into small crews, the neophytes studied signaling, Lewis machine guns, motor work, dual instruction, and finally solo flight, utilizing Curtiss F Boats—small, two-place, pusher-type, single-engine flying boats.28 Artemus “Di” Gates, who had flown in 1916, led David Ingalls’s crew, which also included Kenneth MacLeish, Kenneth Smith, and Robert “Pat” Ireland.29 Ingalls made his inaugural flight in early April, accumulating two hours of dual instruction in the first week, and he soloed on May 8. By late July, the unit logbook documented Ingalls’s nearly fifty hours in the air.

McDonnell’s work with the Yale Unit in Florida and later in New York mirrored similar ad hoc efforts in many parts of the country. Lacking sufficient capacity at its single training station in Pensacola, the navy turned to a variety of stopgap measures until larger facilities and formal courses of instruction began functioning. A group of Harvard students and a few others trained at the Curtiss Flying School in Newport News, Virginia. A second Yale unit commenced instruction in Buffalo and a third at Mastic, New York. State naval militia units began work at Bay Shore, New York, and Squantum, Massachusetts. Several Princeton fliers gathered in Rhode Island before transferring to Royal Flying Corps schools in Canada. These soon-to-be pilots, joined by a group of enlisted personnel just beginning a course of instruction in France, provided the backbone of early naval aviation efforts. The navy’s frantic actions to speed aviators to the battlefield resembled the even larger campaign by the U.S. Army to supplement its still undeveloped training system. Four aerosquadrons’ worth of pilots trained in Canada in the summer and fall of 1917. In September, the first of 450 fledglings departed for England for flight training. At the same time, hundreds more began receiving instruction in France and even Italy.30

But for most, the shooting war was still a long way off. Instead, the Yalies found Palm Beach a pleasant spot, and when not working, they enjoyed swimming, partying, hunting, athletics, various pranks, and relaxing. The group also began planning to relocate operations to northern waters and in June shifted their base from Florida to the Castledge Estate at Huntington Bay, on Long Island, New York, not far from the Davison home at Peacock Point. Facilities there included hangars, runways, and machine shops accommodating a growing assortment of aircraft, including N-9, R-6, and Burgess-Dunne-type float seaplanes. Training continued; flight tests began in late July and extended into August. Soon, newly commissioned officers received orders dispersing them to Washington, Buffalo, Virginia, Florida, and elsewhere. Many headed overseas, with the first pair departing in mid-August. Ingalls followed a month later.31

Hotel Salt Air, West Palm Beach, Fla., April 29, 1917

My Dear Mother and Dad,

Today we rested and slept, thank goodness. It is Sunday and luckily tomorrow our instructors are going to fly to Miami so we shall have nothing to do. They tried it last Sunday but it didn’t come off for some reason. It is to tell the truth a foolish project anyhow, as it does no-one any good except the fellows that are instructing. Last night there was some excitement at the hangars. About two o’clock one of the soldiers on guard left his post to get a drink and on returning perceived a man stealing towards one of the machines. He immediately yelled halt and called the guard. The man ran out on the pier pursued by the guard who fired continually. All of them however fell over a rope anchoring a machine and before they got up the fellow had gotten far out into the lake in a speedboat. They fired some more till he was out of sight. This morning we all gazed with awe at the holes in trees, pier, ground, etc., from those simple soldiers’ guns.

We had a fine week flying as the juniors had almost all gone North for their initiation, so we got a lot of flying. I am now in a squad with Caleb Bragg as our instructor. He is an old automobile racer and one of the best and most careful men in a flying machine I’ve seen. Since entering this squad I have learnt considerable. Our destination has at last been decided on. We are going to a place called Huntington on Long Island about fifteen miles from Glen Cove. It is an ideal place, well sheltered and equipped, and we ought to have a wonderful time there. Almost died yesterday of surprise for I got a letter from Al. He seems to be in pretty good spirits. I also hear that a lot of fellows including Brewster Jennings have been called for training in small boats to chase submarines. Brewster, the lucky dog, is stationed at Newport. He certainly does not miss much.32 Mother, you needn’t bother about keeping those photographs. It doesn’t make any difference. If I get some good ones I’ll keep them. Am thinking about getting some kind of Kodak like a Brownie to take pictures in the air. Much love, Dave

May 13, 1917

Dear Dad,

Today I just had a swim and some tennis, as we have a pretty darn good time on Sundays. Also received some good news. It has been definitely decided to go north on the 1st June to Huntington. We had a fine week last week. The weather was pretty good and what was even better I at last am flying alone for the last week. It is much more fun, as you can do anything you want, excepting that our Lieutenant [McDonnell] has absolutely forbidden anything but straight flying—no so-called trick flying. Until last Monday I had done nothing but practice starting, landings, and turns, especially landings, which for a beginner are about the hardest things. All but about ten or twelve fellows are now alone so we are really at last progressing. As soon as I got out alone I went up high—about 3,500 feet, as I never went up before, always been practicing landings. It is certainly great up there and you own the world when you get up alone and can do what you want. Up, except on a very rough day, there is almost nothing to do, as it is perfectly calm and I just set and looked down. It’s funny but you never feel sick looking straight down and you can see for miles. I saw several tremendous fish in the ocean, as you can see down very far. There were a few small, light clouds, and I went through them; you can’t see a thing and have to balance by feeling, which is pretty hard. Also a rain cloud or black clouds are full of puffs [of wind] and few people go through them.

I never enjoyed anything as much as going up there and guess I’ll have to do it again soon. The only trouble being it takes a lot of time and you get no experience, as it is so calm, while from about 1,200 feet down there is almost always a lot to keep you busy, as even on a pretty calm day there are loads of puffs and pockets, so you are always on edge. Till Wednesday I took along a sand bag, but didn’t from then on. It was to keep the balance the same, in place of the instructor. Our boat happens to be nose heavy, however, and it is very hard to fly alone, so we are always going to use a sand bag.

Wednesday I almost got into bad trouble. Having left the sand bag behind, the machine was very tail heavy with a tendency to climb and it was work to keep pushing down the “flippers” to go level. Then when I started to come down from about 1,000 feet for my first landing I started off at too steep an angle and went so fast that my goggles began leaking and my eyes watered till I couldn’t see at all, so I leveled off to what seemed about right and pulled off the glasses, so I could see all right, but being afraid of coming down too steeply again I went to the other extreme and pancaked down for the last 200 feet, much too flatly, losing all speed and thus use of my controls. Fortunately, I appreciated it after dropping 100 feet and made a good landing, but if I hadn’t and a bad puff had hit me I would have made a bad landing. Just after, when coming down again to land a bad puff hit me and I got into a sort of sideslip—not a bad one, and I got out of that all right. A sideslip is when you get rocked over sidewise at such an angle that the machine starts to slide down edge first. You seem to come to a stop in forward motion and it is a horrible feeling.33 Fortunately it was not a bad one, however, and I righted the machine before it got much speed. Also it was high up. Height is the most important thing, as if you should ever get into a sideslip at about 100 or 200 feet before you could get out you would hit the water sidewise, which would bust things up. That was a bad day for me. I don’t know why, one seems to fly rather erratically and I made a lot of routine landings, in addition to the first one, which was really dangerous. The lack of the sand bag helped in putting the bow up and tail down on landing, also helped in my pancaking, as I had to push the controls as far forward as possible to get out of the pancaking, and then barely did. That afternoon the Lieutenant took up our machine and made a rotten landing and said that we always had to carry the sand bag, as it was hard to run it otherwise. That sand bag certainly made a difference and I flew pretty well then, and Friday, till our plane’s engine busted and now we have to put in a new one, and there being no engines ready, we had no flying Saturday and won’t get any till Tuesday.

It is funny how much feeling there is about flying. Everybody is jealous—talks about how others go and always count the bumps if anyone makes a bad landing. A bump is when you do not slip into the water just right and sort of bump into the air. A couple of inches difference in where you level off or a touch of the controls at not the right time will sometimes bump you up 30 feet or higher. Usually though you just go up a foot or two and that is a bad landing, but most everybody bumps sometime. I was certainly put in a better humor after flying so badly Wednesday when I saw everybody almost when they came in bump, and the Lieutenant gave them the deuce. Luckily I made a good landing coming in so that was all right. But someone else who was out saw me make some rotten ones and I got the—pretty well.

Well, Dad, I’ve got to go to dinner. Sorry I didn’t write you before about what I was doing, but I wanted to fly alone first. Lots of Love, Dave

Ingalls Memoir re: Palm Beach

The first crew I was on was in charge of “Di” Gates, with “Ken” MacLeish, “Ken” Smith, and “Pat” Ireland. The competition was keen between crews. Each wanted to have the best machines and the most flying. So we went at it hard when anything needed fixing. To work one had to have tools, and to keep a machine in good shape you tried to find the best motor cover. “Di” would tell us to get something and leave us to go and get it. As burglars we were good. We became very clever at picking up good motor covers that were lying about. When we had wangled something we wished to keep we painted a big number on it. And friends were base enough to call us crooks!

There was never a thought about how much or how little we were working. The more we did the more we flew, and that was the mark we were shooting at. But it did come as a slight shock, after we had been there almost two months and had lugged gas and oil daily to the machines, to have Lotta Lawrence come wandering along with two empty cans and ask where a guy could procure some petrol.34

According to Harry Davison:

One day Crock [Ingalls] and I certainly slipped it over the rest of the outfit. We got up long before it was light and went down to the machines. We got old Number 3 out just as dawn was breaking. Then we had one of the prettiest flights that ever happened, for about an hour. We went up about 3,000 feet and watched the sun rise. Everybody was terribly snotty about it when we came down. They all tried to work this same stunt, but Lieutenant McDonnell forbade it after that.35

U.S. Naval Reserve Flying Corps Detachment36

Huntington, Long Island, July 1917

Dear Mother and Dad,

Sorry not to have been able to write you before but we have had a busy time taking a test on a book by a man named Loening. Isn’t it just the luck, since you left we have had wonderful flying weather and have been flying a lot. For instance yesterday I had two hours and my time is very short because they are giving extra to a lot such as Ireland, etc., to make them catch up. (I had been sick.) Thursday the two N-9 machines arrived and are now in commission. They are pontoon machines and pretty handy good machines. Also Monday we received a Wright Martin pontoon machine, a wonder.37 More machines are coming soon. In a little more than a week we are going to take our tests for Naval air pilots, which I hope will not be hard. Saturday we had quite a time, first in the afternoon several of us including little me flew over to the Davisons,38 circled around the polo field a bit on which thousands had aggregated, and then landed, watched a base ball game between our team and one from Mineola, our side winning, then flew back. There was a lot of trick flying by the Mineola land machines, and at one time there were at least 25 or 30 machines up. It must have been quite a sight. Saturday night I had dinner at the Davisons and then went to a dance at H. P. Whitney’s. Had a great time Sunday and came back that night on the yacht with all the wireless girls to accompany us.39 Am feeling rather sleepy now as I went out to dinner Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday after you left, also last night, so have now sworn off parties with Harry. Must stop, lots of love, Dave

According to William Rockefeller:

We [Rockefeller, Ingalls, and MacLeish] made several flights over submarines operating in the [Long Island] Sound while they tested out various devices by means of which they hoped to be able to detect the presence of aircraft. Submarine officers also took flights with us to observe the visibility of subs while submerged under different conditions. I had my one and only trip in a submarine at this time, as the officers kindly let us go out with them when we were not otherwise occupied. I don’t want another ride. All I remember is a good deal of noise, being told I was under the Sound, seeing the water go through the little glass portholes in the conning tower, or whatever it is called, and coming up again.40

Reginald “Red” Coombe said of flying at Huntington:

The flying got a little smoother as time went on. . . . It was not an uncommon thing to see Ingalls flying upside down or doing tailspins in the largest boat.41

On Board Whileaway,42 July 31, 1917

My Dear Mother,

Awfully sorry not to have had a second to write you before but we’ve been awfully hard worked. Also we’ve had a couple of accidents, about which I hope you won’t worry. Harry had a fall from side slipping then nose dived from about 500 feet, and two days after Truby [Trubee Davison] did the same thing from about 300 feet. Harry was absolutely unhurt, thank goodness, but Truby was not so lucky as he did something to his back. The doctors say he will be alright in about three months.43 So, as a result they have let up on us a lot, as I believe they think the fellows were a bit tired. So today we are spending this afternoon on the boat and this morning I slept all morning. Now I am feeling fine and hope to take my test for naval pilot next Monday. About eight fellows, the ones who flew last summer, passed their tests Saturday, Sunday and Monday and most of them will be going to other places to instruct.44 In about two weeks we’ll probably be separated all over the country instructing. As soon as some decent machines are made, say two months, fifteen of us are probably going abroad first to instruct there. I don’t know who will go. I hope you are having a great time, as good as I had last summer, also Al. Please give my love to all the Tafts. With love, Dave

Reg Coombe recalled:

I remember one day the phone rang up in the house and it was Washington on the wire. The news soon spread around and pretty soon all the Unit that were left were around that room waiting to hear what the news was, and the chief yeoman who was on the wire would repeat the orders as they came along: Landon, France; then a big yell; Ingalls, France, and so on.45

2

Early Days in Europe

September–December 1917

During the summer and early fall of 1917, several members of the Yale Unit received orders to proceed overseas, where the navy had begun creating an extensive system of patrol stations, flight schools, and supply bases from scratch. With aviation officers in very short supply, the Yale gang offered nearly the only available source of additional trained personnel. In fact, the navy had not yet dispatched a single flying officer to Europe for combat duty. A small force of 122 enlisted men, the First Aeronautic Detachment, reached France in early June, their exact training and mission yet to be determined. Four commissioned fliers accompanied them—Kenneth Whiting, Godfrey Chevalier, Virgil Griffin, and Grattan Dichman—with orders to oversee training of their enlisted charges. They later assumed a variety of administrative and staff positions. A few other aviators arrived during the summer, either to investigate conditions in Europe, to gather technical information, or to fill out expanding staffs in Paris and elsewhere. Until the navy’s new ground and flight schools in the United States functioned smoothly, however, pilots to conduct antisubmarine missions necessarily came from the first college groups hastily trained in the spring and summer of 1917.46

Bob Lovett and Di Gates of the Yale Unit departed first for the war zone, sailing to England in mid-August.47 Fellow unit members John Vorys and Al Sturtevant soon followed.48 A larger contingent, consisting of David Ingalls, Freddy Beach, Sam Walker, Ken Smith, Reginald Coombe, Chip McIlwaine, Henry Landon, and Ken MacLeish, received orders to travel in late September aboard the old liner Philadelphia, now pressed into service as a transport.49 They all looked forward to their new duties with a mixture of excitement and trepidation. David Ingalls began keeping a diary, what he called “this simple book,” while aboard Philadelphia, and with only a few interruptions, he continued to do so until the war ended fifteen months later.

Like so many Americans crossing the submarine-infested Atlantic in the fall of 1917, Ingalls experienced the exhilaration and occasional panic of traversing the war zone. According to cabinmate Henry “Hen” Landon, they heard many wild rumors and thrilling stories while aboard, so many that they slept in their clothes, with their .45 service Colts close by. When fellow aviator Ken Smith spotted a porpoise knifing through the waves, Landon “nearly died in [his] tracks,” expecting an explosion to send their ship to the bottom.50

Despite such fears, the crossing proved relatively peaceful. Ingalls and the others landed safely in Liverpool, the great entrepôt on the Irish Sea, and had their first real contact with a nation at war. One enlisted sailor on his way to NAS Dunkirk called Liverpool “a quaint looking old city,” nothing like those at home, lacking skyscrapers and featuring crooked streets “that could break a snake’s back.”51 Newly arrived Americans spotted women working everywhere, out in the streets and in all the stores. Then it was on to London, where Ingalls and his companions toured the metropolis and began their naval duties, sometimes with comical results. They found the wartime scene eye opening—railroad stations crowded with troops and ambulances full of casualties just back from the front. Ubiquitous wounded soldiers sported blue stripes on their sleeves that indicated they could not purchase alcohol; authorities claimed abstinence promoted convalescence. Only a few months removed from happier college days, the Americans sensed despair in the populace.52

Ingalls and the others quickly checked in at the Savoy Hotel and readied themselves to report to navy headquarters at 30 Grosvenor Gardens. This formal duty required being properly turned out, a task somewhat beyond the ken of recently minted ensigns. Ingalls and two friends appeared in the service’s new forest green aviators’ uniforms, with Sam Browne belts and swagger sticks. The others donned dress blues, yellow gloves, and swords, but they could not quite figure out how to wear the ceremonial weapons. A few sarcastic remarks from headquarters staff sent the youngsters packing with, according to Ken Smith, “our tails between our legs.”53

Embarrassed but unbowed, they visited British military facilities before continuing on to Paris. On October 9, Ingalls departed London, headed for the Continent via a Channel steamer out of Southampton. The crowded vessel carried hordes of soldiers returning to the front, nurses, and civilian officials, and accommodations could not be found. Instead, the Americans made the best of it, eventually landed at Le Havre, and attempted to negotiate customs and baggage handlers with a working vocabulary of only three or four French words. After an interminable railroad journey, they reached Paris at three o’clock in the morning, piled into a small fleet of decrepit taxicabs, and eventually washed ashore at the Grand-Hôtel.

War-torn France presented an arresting and varied tableau. George Moseley, a football star at Yale and friend of many in Ingalls’s unit, noted that “women customs officials and examiners were the first sign we had of the lack of men.” Continental timekeeping also intrigued him, with its “22 hours 40 minutes instead of 10:40,” and a visit to the barbershop proved dispiriting, “full of common French soldiers, the poilus in their blue uniforms. . . . They seemed very sad, never smiling, and lonely talking now and then.” Moseley could not escape wartime realities: “I noticed a number of women who were standing back of me (they were all in mourning, nearly all the women in France are in mourning).” Bob Lovett echoed these maudlin observations. Writing home to the convalescing Trubee Davison, he reported, “The condition of France you would be heartbroken. She is staggering with the weight of the war’s toll, but even more to my mind under graft, honest to goodness rotten politics, and self-interests. . . . We have heard stories about men shooting their officers from sheer desperation rather than spend another winter in the hell of the front.”54

After reporting to aviation headquarters at 23 Rue de la Paix,55 Ingalls and the recent arrivals received orders, somewhat to their surprise, to head down to the infant navy school at Moutchic, about thirty miles from Bordeaux near the Bay of Biscay, rather than the French school at Tours where earlier aviation candidates had trained. There, they would learn to pilot larger aircraft such as the Franco-British Aviation (FBA) and Donnet-Denhaut flying boats,56 similar to the types purchased for use at American patrol stations then under construction along the coast.