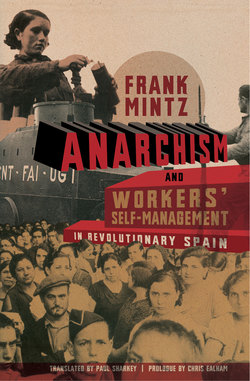

Anarchism and Workers' Self-Management in Revolutionary Spain

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Frank Mintz. Anarchism and Workers' Self-Management in Revolutionary Spain

Copyright Information

Prologue

Introduction: Self-Management and Anarcho-Syndicalism

Chapter One: Introducing the Anarcho-Syndicalist Movement, the CNT

Chapter Two: Catalonia as a Model: Self-Management Emerges in Barcelona; The First Contradictions

Chapter 3: A Brief Survey of Self-Management in Other Regions of Spain

Chapter Four: Organising Self-Management across the Nation

Chapter Five: Self-Management under Attack

Chapter Six: Self-Management’s Outcomes: Overall Conclusions and Estimates

Chapter Seven: Conclusions about Self-Management in 1936–1939, and Broad Reflections

Introduction to Appendices

Appendix I: Notes on the Spanish People’s Superficial Catholicism

Appendix II: Revolutionary Uprisings in Spain, 1932–1934

Appendix III: One Example of Monetary Reform and Scheme for Currency Circulation in a Social Economy296

Appendix IV: The CNT and the FAI: Pressure Groups (1998 [revised 2005])

Appendix V: The Two Libertarian Communisms, or, the Libertarian Party versus Anarcho-Syndicalism (revised 2005)

Appendix VI: Notes on Governmental Collaboration

Appendix VII: Making Sense of the Plenum of Confederal Militias and Columns

Appendix VIII: Evidence about the Collectives of Ascó and Flix (Tarragona), and the Barcelona Barbers’ Collective360

Appendix IX: The Madrid Peasants’ Collective361

Appendix X: The Adra Fishermen’s Collective364

Appendix XI: The Artesa de Lérida Collective365

Appendix XII: The Barbastro Comarcal Federation of Collectives366

Appendix XIII: UGT CNT CLUEA. Citrus Fruit Exports from Revolutionary Spain, 1936–1937367

Appendix XIV: The Establishment, Growth and Operation of the Barcelona and District Locksmiths’ and Corrugated Shutters Collective378

Appendix XV: Marx, Engels, the CP, Councilism, Historians and Revolutionary Spain

Appendix XVI: Francoism, Transition to Democracy and Thoughts on Collective Management (written 1997–1998)

Glossary of Terms and Initials Used in the Text

Index

Отрывок из книги

Frank Mintz’s classic study of the Spanish revolutionary collectives—now revised and available here in English for the first time—is a penetrating analysis of the most extensive and deeply rooted experiment in workers’ self-management since the advent of capitalism. It is also a book with a mission. If E. P. Thompson’s famous motivation was to rescue the history of the British working class from the ‘condescension of posterity’, Mintz was inspired by a far more overarching objective: to penetrate the wall of silence erected around Spain’s revolution of 1936. Spain’s revolutionary experience, the great beacon of hope in the prevailing darkness of what Victor Serge dubbed the midnight of last century, was devoured by a civil war that was almost immediately eclipsed by the horrors and Holocaust of World War II. As the first chill winds of the Cold War scattered dust and fog across the rubble of post-war Europe, from Madrid to Moscow, the grand narratives of the victors’ versions of history—be it Stalinist, liberal-left or Francoist—all ensured that the Spanish revolution became shrouded in silence, or, at a minimum, distorted beyond recognition.

For decades, the historiography of 1930s Spain confirmed the maxim that the history of ‘failed’ revolutions tends to be ignored. During the long winter of Francoist dictatorship, the apologists of the regime imposed an official bi-polarity on the history of the 1930s, constructing a division between the forces of ‘good’ and ‘evil’, of ‘Spain’ and ‘Anti-Spain’. Prominent here was policeman-Historian Eduardo Comín Colomer, who used police archives as the basis of his calumnies against the anarchists, who were depicted as having imposed themselves on an otherwise law-abiding working class. Yet the exigencies of the Cold War, so adroitly exploited by the dictatorship for its self-preservation, led to an even greater distortion: in its readiness to highlight the ‘red menace’, Francoist historiography downplayed the role of revolutionary anarchist masses in the 1930s, prioritising instead organised Stalinism, a force that, prior to the civil war, was largely insignificant on the Spanish left. Thus, the red-and-black that heavily inflected the collectivisations was recast as a ‘red revolution’, a legend that was extremely flattering for the official communist movement.

.....

In 1922, a CNT delegation was dispatched to the launch of the Third International in Moscow, and decided not to affiliate to the new International in light of the situation of anarchists and the Russian workers. Two Marxists in the delegation—Andrés Nin and Joaquín Maurín—then quit the CNT, and went on to launch the POUM.32

But more serious developments were afoot: the Catalan employers, out for revenge over the La Canadiense strike, armed men who gunned down trade union officers, including the man who had been the inspiration behind the strike tactics—Salvador Seguí. This was the era of pistolerismo (pitting the ‘hired killers’ against the syndicalists). In response, the defense groups were formed. There was all-out struggle between 1919 and 1923.

.....