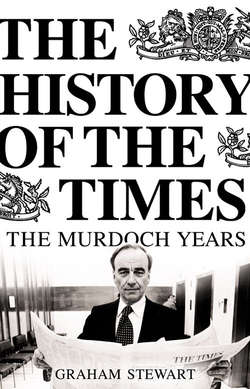

The History of the Times: The Murdoch Years

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Graham Stewart. The History of the Times: The Murdoch Years

THE HISTORY OF THE TIMES

GRAHAM STEWART

CONTENTS

PREFACE

CHAPTER ONE A LICENCE TO LOSE MONEY

I

II

III

IV

V

CHAPTER TWO ‘THE GREATEST EDITOR IN THE WORLD’

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

CHAPTER THREE COLD WARRIOR

I

II

III

IV

V

CHAPTER FOUR ANCIENT AND MODERN

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

CHAPTER FIVE FORTRESS WAPPING

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

CHAPTER SIX FIFTY-FOUR WEEKS UNDER SIEGE

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

CHAPTER SEVEN INDEPENDENT CHALLENGES

I

II

III

IV

V

CHAPTER EIGHT STURM UND DRANG

I

II

III

IV

V

CHAPTER NINE SIMON JENKINS

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VII

CHAPTER TEN CRITICAL TIMES

I

II

III

IV

V

CHAPTER ELEVEN THE HEART OF EUROPE

I

II

III

IV

V

CHAPTER TWELVE NEW LABOUR, NEW JOURNALISM

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

CHAPTER THIRTEEN WAR IN PEACETIME

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

CHAPTER FOURTEEN DUMBING DOWN?

I

II

III

IV

V

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PLATES

NOTES. CHAPTER ONE: A LICENCE TO LOSE MONEY (PP. 1–44)

CHAPTER TWO: ‘THE GREATEST EDITOR IN THE WORLD’ (PP. 45–118)

CHAPTER THREE: COLD WARRIOR (PP. 119–166)

CHAPTER FOUR: ANCIENT AND MODERN (PP. 167–218)

CHAPTER FIVE: FORTRESS WAPPING (PP. 219–252)

CHAPTER SIX: FIFTY-FOUR WEEKS UNDER SIEGE (PP. 253–299)

CHAPTER SEVEN: INDEPENDENT CHALLENGES (PP. 300–331)

CHAPTER EIGHT: STURM UND DRANG (PP. 332–366)

CHAPTER NINE: SIMON JENKINS (PP. 367–415)

CHAPTER TEN: CRITICAL TIMES (PP. 416–471)

CHAPTER ELEVEN: THE HEART OF EUROPE (PP. 472–496)

CHAPTER TWELVE: NEW LABOUR, NEW JOURNALISM (PP. 497–558)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: WAR IN PEACETIME (559–609)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: DUMBING DOWN? (PP. 610–650)

BIBLIOGRAPHY. Newspapers and periodicals

Books

INDEX

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Отрывок из книги

This is an official history. It has access to private correspondence and business documents that have not been made generally available to other writers or historians. Some may consider this a mixed blessing and assume that the consequence must necessarily – in the words of the accusation that used to be labelled at The Times’s obituaries – ‘sniff of an inside job’. It should therefore be stated from the first that at no stage has anyone altered anything I have written or pressured me into adopting a position or opinion that was not my own. It is an official history but not a formally approved or authorized version of events.

Indeed, Rupert Murdoch’s relaxed attitude while I probed around in an important part of his business empire contrasted favourably with past precedent in this series. Those commissioned to write the six previous volumes of the official history of The Times were closely involved in the paper’s life, a conflict of interest that certainly hindered the appearance of objectivity. The first four volumes, covering the period between its foundation in 1785 and the Second World War, were compiled between 1935 and 1952 by a team under the command of Stanley Morison. Morison was the inventor of the world’s most popular typeface, Times New Roman. He was also a close friend of the paper’s then owner, John Astor, and its editor, Robin Barrington-Ward, who went so far as to describe Morison as ‘the Conscience of The Times’. Iverach McDonald, who was an assistant editor and managing editor of the paper during the period he described, wrote volume five in 1984. Volume six, covering the years 1966 to 1981, was written in 1993 by John Grigg. He had been the paper’s obituaries editor between 1986 and 1987 and was a regular columnist. Grigg, at least, was not directly involved in the events about which he wrote. Instead, he brought the insight and flair of the independent historian of note, attributes for which he will be fondly remembered. For my own part, I cannot claim much personal involvement with the paper during the years covered in this volume. My only first hand experience was garnered during the year 2000, when I was a leader writer. As a historian, my specialist area is British politics in the 1930s.

.....

From the moment of Keith Murdoch’s Dardanelles scoop, he had the attention and support of Lord Northcliffe. The owner of The Times became a mentor for the motivated Australian, inspiring him and including him in his influential social circle. And Murdoch learned a good deal from the man who had done so much to create the mass-appeal ‘new journalism’, launching new titles and rejuvenating old ones like The Times. When Murdoch struck out on his own, taking up the editorship of Australia’s Melbourne Herald, Northcliffe even went over there to sing his praises. The Herald’s directors soon had cause to join in: circulation rose dramatically and its editor joined its management board, buying other papers and a new medium of enormous potential – a radio station. Growth would be fuelled by acquisition, creating a business empire in a country in which the print media was entirely localized. It was also a route to making enemies who believed Keith (from 1933, Sir Keith) Murdoch’s expansionist strategy not only gave the Herald and Weekly Times Group too much financial clout but also made its managing director a kingmaker in Australian politics as well. The Herald Group’s competitors were especially dismayed when with the outbreak of the Second World War he was appointed Australia’s director-general of information. The role of state censor was certainly not in keeping with the role he had played in the previous conflict. But when, in 1941, ten-year-old Keith Rupert Murdoch arrived at boarding school, it was to discover to his surprise that it was his father’s crusade to bolster the power of the press that was often looked at with mistrust and apprehension.

Though he showed little interest in Geelong’s emphasis on team sports, Rupert Murdoch’s childhood had been predominately spent outdoors with his three sisters riding and snaring (Rupert persuaded his sisters to skin the unfortunate rodents for a modest fee while he sold on the pelts at a larger mark-up). Home was his parents’ ninety-acre estate, Cruden Farm, thirty miles south of Melbourne. The house itself was extended over the years and by the time Rupert was growing up there it resembled the sort of colonnaded colonial residence more generally associated with Virginian old money. But rather than be overexposed to its creature comforts, Rupert spent his evenings between the ages of eight and sixteen in a hut in the grounds. His mother thought it would be good for him.[96]

.....