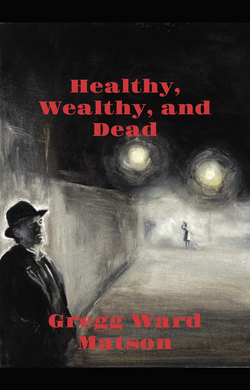

Читать книгу Healthy, Wealthy, and Dead - Gregg Ward Matson - Страница 1

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Park

ОглавлениеCoincidence? She didn’t think so. In her mind, every incident has a purpose. I’m trained to think coincidences are just that. She didn't believe the coroner's report. I’m a detective, with Attention Deficit Disorder. I know, an odd choice of jobs. We met, "coincidentally," and that led to murder.

I routinely walk around or through Capitol Park, which surrounds California’s Capitol. The money that flows through that noble-looking building…the crimes people commit to get some of that money…amazing. Most of the time they get away with it, too, simply by having politicians change the laws to make their crimes legal. They often tweak the letter of the law, and occasionally gang rape the spirit. But the sheer volume of larceny is so stunningly ordinary, that it usually get ignored. Try to make sense of it, try to do something about it.

Better just enjoy the scenery in Capitol Park: trees from the world over, shrubs, grass always green and cut. Roses, cactus, iris—color always in season. It’s even nicer after the bureaucrats and kleptocrats go home to the suburbs, like a party when the guests are finally gone. Then the winos and locals with nothing to do—the people who actually belong there—move in and make themselves at home. I feel at home then, too.

I live nearby. I work nearby.

On that particular day, in December ninety-six, the kind of day that makes you look inside and see things you don’t like to see, I passed the Vietnam Memorial. I usually stay away. Guys my age lost their lives and got their names printed on cement. Some people said it was a noble cause. It’s depressing. Still, there I was, for no logical reason, on that foggy day. A faint glimmer of weak sun stuck out above the cold mist and the dripping, leafless trees. She happened to be there, standing by those pillars that resemble spent shell casings more than anything else, looking thoughtful. I hadn’t seen her since high school; she looked vaguely familiar, although she hadn’t changed much.

She saw me. “Marvin?”

“Yeah….”

“Loralee Danwick.” She smiled. All her teeth were there, straight as soldiers and white as milk. “You’re Marvin Kent, aren’t you?”

“Oh, yeah, Lolly. Sorry, it’s been forever.”

Her blue eyes gleamed, burned through me, rummaged in there, took what they wanted, then looked away. “Loralee Carlisle now. I use my full name in my old age. Before that it was Morehouse.” She shrugged. “That’s who I’m visiting now.” She pointed, gracefully, at the nearest monolith covered with smooth black panels, panels full of names.

She showed me a name: “Capt. Morehouse, Charles F. 27, USAF.” I nodded, having nothing to say, knowing that nothing was probably the wisest thing to say. I looked her and nodded again.

Though she had a few wrinkles, she looked like a fit twenty-five year-old would want to look. She wore a purple padded jacket that stopped at the hips. Below that she wore blue skin-hugging pants, and floppy, black, ankle-high boots. Being a detective, I notice things. I noticed that hers were legs that could truly wear mini-skirts both times around, first in the sixties, again in the nineties. There were damn few legs that could do that. I’d seen perhaps two, and I was looking at both of them.

I started to get some ideas, to wonder if there were some angles I could work to get, well…closer.

“Chuck was a career man, on his second tour of duty,” she said, as those blue eyes burned through me again. “He caught a missile over Haiphong harbor. His jet flamed out and crashed into the ocean. They never found his body, but they know he died.” She smiled one of those tight, fabricated smiles, the kind that conveys no mirth. “A couple months later they signed the peace treaty.”

I smiled back, hoping to convey sympathy. Even now, after all those years, it’s still smart to be very careful about what you say concerning Vietnam. That is, if you must say something.

“I was well taken care of. He had his G.I. insurance and his family was wealthy. But they had good lawyers who got me declared unfit, and took my children away.” She was still smiling that phony, face-cracking grin. Her face started showing a few of the lines that fifty years earn. “What kind of adults do children grow up to be when they lose their father in a war and right afterward their mother in a lawsuit?”

I had no answer.

Her smile softened. “But what about you, Marv? I hate people who do nothing but talk about themselves. So don’t let me do that. Are you married?”

“Divorced, for about ten years. I have a daughter. Joint custody, but same feelings—about, you know, missing your kids.”

She put on that plaster smile again. “Well, at least we get to mess up into our old age.” She looked back at the rock with names on it.

I nodded. She was telling a virtual stranger some personal facts. Why? Grief? In my line, I work long and hard, trying to get people to reveal the truth about themselves. I’m not used to frankness.

She turned back to me. “So what are you doing these days, Marvin?”

“I’m a private investigator.”

Her eyes widened, the way everyone’s eyes widen when they find out they actually know “one of those.” She giggled. “Really? Like Jack Nicholson or Humphrey Bogart or—what’s his name? Efrem Zimbalist Junior?”

“No, it’s kind of a boring job.”

“Funny. Don’t take this wrong, but I always thought of you as a farmer. You know, the country type.”

I laughed. “I missed my calling. I still dig up dirt, though.”

“I guess you do. Well, would you like to know what I’m up to? You know, I used to have quite a crush on you when we were about fourteen.”

This was amazing news. The wheels started turning, until I remembered she had a third last name. The machinery ground to a halt. I recalled that my friends--goof-offs and loudmouths--never did have much in common with her circle of drama-artist types. But she was certainly my type now. “You kept that a big secret,” I said.

“When you’re fourteen you keep everything a secret. Don’t you remember how godawful hard it was, to have all those feelings swirling around, and scared to bare them because you’ll be punished or even worse, ridiculed?”

“Sure do. So what are you up to now?”

“I’m an artist.”

“Still?”

“Always.” She smiled, a real smile. “Sculpture, poetry, dance, music, painting, theater. I do it all. I have nothing to do but explore what’s going on inside.”

“Well, it seems to suit you. You look great, Loll-Loralee.”

“Thank you. You have many opportunities for self-expression when both your husbands have died and left you a fortune.” She didn’t seem overly happy about that.

“I see.” The machinery chugged to a start again.

“And now I’m dating a man who is even richer than my late husbands. Filthy, obscenely rich.” She didn’t seem any happier.

The machinery stalled again. I smiled. “Good seeing you again, Loralee. After all these years. You do look great.”

“Thanks. Good to see you too.” She stepped forward to hug me. In California you can hug women even when you don’t know them very well, and I try not to turn a hug into a grope. Still, fifty isn’t that old.

When the hug was over we exchanged the customary look and smile, and for just a sliver of a moment she closed her eyes and opened her mouth and looked like she was ready for a kiss. Then she opened those bright blue eyes, gave me a jolly look as she let go and stepped back. “By the way, what is your fee?”

That was a shock, but I recovered. “Three-hundred a day, plus expenses. And a fifty-dollar a day charge for things I can’t itemize. If I don’t spend it I give it back.”

“How do I know you’re honest?”

“If you’re honest you’ll know.”

“That’s awfully cheap.”

“I don’t often hear that. Usually they howl like they’re being disemboweled. Even rich folks. Especially rich folks.”

“I suppose if you worked full time you could do okay. Do you work steadily?”

“Not always.”

“Do you have a card? I might have some business for you.”

“Sure.” I handed her my card, which she took with long, thin, graceful fingers, put it into a billfold made of some kind of leather that wasn’t cow. “Give me a call,” I said.

“I think I will. Take care.”

“You too.” With another smile and nod, we went our separate ways. I made sure we didn’t run into each other after we’d parted. I assume she did the same.