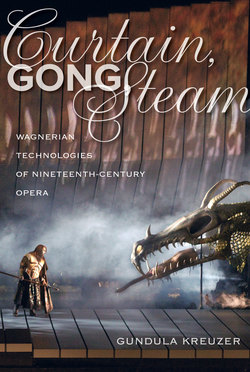

Curtain, Gong, Steam

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Gundula Kreuzer. Curtain, Gong, Steam

Отрывок из книги

Curtain, Gong, Steam

The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation also gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Constance and William Withey Endowment Fund in History and Music.

.....

Understandably, media and performance scholars have therefore tended to place Wagner at the beginning of a growing intersection of theatrical and technological modes of representation. In their view, Wagner spearheaded an emerging alliance of aural and visual media that ultimately led to their convergence in our virtual age. For instance, Wagner looms large in the work of German media theorist Friedrich Kittler, who regularly referenced the Gesamtkunstwerk as a “monomaniacal anticipation of the gramophone and the movies.”55 Multimedia artists and theorists have likewise dated the emergence of contemporary media performance with Wagner. Chris Salter starts his survey of the modern “entanglements” of mechanical (or computational) technologies and performance with Bayreuth, while Randall Packer and Ken Jordan prominently discuss Wagner as having made “one of the first attempts in modern art to establish a practical, theoretical system for the comprehensive integration of the arts.”56 His struggle for “aesthetic totality” as well as the Gesamtkunstwerk’s dialectically related reliance on mechanization is the connective tissue that allows literary scholar Matthew Wilson Smith to link Wagner to film, Disneyland, and virtual performance.57 And according to historian of modern art and media Noam Elcott, Wagner’s Bayreuth theater was unique among audiovisual devices of its time because it alone “could accommodate countless types of performances and images,” with its “most significant legacy . . . its adoption by cinemas.”58 In short, Wagner is frequently equated with his Bayreuth theater, which in turn tends to be construed as a historically new amalgamation of arts and modern technologies. His artistic vision has become a convenient reference point for bestowing both historical roots and a weighty artistic heritage on the development of cumulative, multisensory, integrative multimedia.

In contrast to such general claims about the media-historical significance of Wagner’s ideals and their manifestation in the form of Bayreuth’s Festspielhaus, I pursue a rich historical embedding of a number of specific yet oft-overlooked technologies. By opening out to a chronologically and geographically wider field of composers, locales, and traditions, these case studies show how Wagner based not only his theories but also his Gesamtkunstwerk’s staged realizations squarely on contemporary practices, and in this sense formed but a step in opera’s development toward medial integration. Curtain, Gong, Steam thus counteracts Wagner’s dominant position in media studies, while my focus on stage practice also serves as a corrective to the almost exclusive reliance of Kittler (and others) on Wagner’s idealized artistic claims. This reliance amounts to nothing less than a romanticized continuation of Wagner’s messianic self-stylization that is weirdly at odds with the otherwise blatant techno-determinism and anthropological skepticism permeating Kittler’s writings.59 After all, the incorporation of technē into Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk was not without its drawbacks, even on the theoretical plane. One indication of this downside is that Wagner remained conspicuously silent about what we might call the mechanical underbelly of his envisioned music drama. Just as he originally charged opera’s music to have oppressed drama, so the three “material” arts that he invited into his drama (though architecture and painting more so than sculpture) now eclipsed the manifold technological underpinnings required to realize his vision onstage. In other words, Wagner’s theoretical recourse to the traditional arts veiled his concrete reliance on mundane theatrical mechanics.

.....