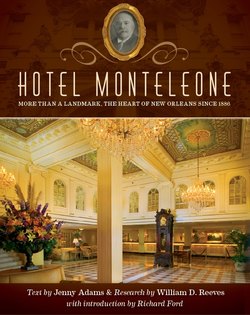

Hotel Monteleone: More Than a Landmark, The Heart of New Orleans Since 1886

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Jenny Ph.D. Adams. Hotel Monteleone: More Than a Landmark, The Heart of New Orleans Since 1886

INTRODUCTION. by Richard Ford

CHAPTER 1. Early History

CHAPTER 2. Growth of the Hotel

CHAPTER 3. Food and Entertainment

CHAPTER 4. Prose, Plots, and Bon Vivants

The Pen and the Page

Setting the Stage

Endnotes

Отрывок из книги

My most enduring memory of the Monteleone— and my most endearing—must’ve originated about 1950. I was six. It was a typical shoe-leather-melting summer day in New Orleans. My mother, to while away the steamy hours and divert her only son, had been taking us back and forth across on the Algiers Ferry for most of an afternoon, letting me stand up in the bow, breathing in the hot, complex, brackishness of the river, watching the city’s modest skyline move away, then draw close again, move away, come near, move away. Pralines are a central feature of this memory. They were on sale at the ferry dock, packaged in small, waxy sleeves, and sold for a dime.

At five sharp, however, we quit our journeying and walked hand in hand up Canal Street, the short stroll to Royal and down the shadowy block and a half to the Monteleone, which was my father’s “headquarters” when he worked his south Louisiana accounts—Schwegmann’s and Delchamps in town, and all the small wholesale grocer concerns down through Houma and over to Lake Charles, up to Villeplatte and Alec, and back again. He sold laundry starch. Faultless. It was a name that meant something then. He’d be waiting for us in the hotel.

.....

Oh, there used to be hotels like this one—or at least close: old, family-owned, family-run accommodations all across the south, all across America. The Muehlebach in K.C. The Peabody in Memphis. The Marion in Little Rock. The Edwards in Jackson. The Bentley in Alexandria. The Drake in Chicago. A few persist today, it’s true: genuine hotels—not “venues,” not “properties” with corporate ice in their veins and precisely planned obsolescence; but honest-to-God establishments, where arriving and checking in was a ceremonious event all its own, with public-private formalities and rituals and assumptions and a cast of memorable employee-characters that all joined in declaring to the weary traveler or the grinning, winking old pol or the young bride and groom: “You’re not at home now. This is special. You’re our guest, not just a customer. We offer comfort and privacy for whatever you require comfort and privacy for. But we’d also like you to feel you belong here, at least for a while.”

Obviously I’m a romantic when it comes to these splendiferous old piles and their gilded trappings—chandeliers and chimes, goldfish ponds and red damask wall coverings, liveried this’s and that’s. I hope I won’t live long enough to see them go extinct. Later in my boyhood I actually resided in one, and in my time I saw parade before me a thousand florid stories, characters, spectacles—a great Scheherazade of a place, featuring (it seemed) the world’s moral miscellany passing every day: pathos, transgression, charity, humblings large and small, unsavoriness and kindness of every stamp. Much of it extremely funny. Not a bad beginning for a boy on his way to be a writer. And I’ve lived long enough to see even that old place of my boyhood torn down, imploded, and a gleaming new ziggurat rise from its rubble. The Excelsior, they called the new place. Quite glittering. And now it’s gone, too, after only thirty years, replaced by something different— all my faithful memories left with no firm locus on which to fix themselves, just afloat, surviving in my dreams.

.....