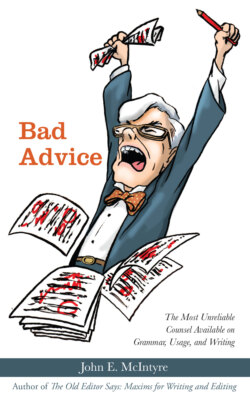

Описание книги

In Britain the monarch is never wrong. Whenever the sovereign drops a brick in public, a functionary turns up at Buckingham Palace to explain that Her/His Majesty “was badly advised.”

In the same way, many of the things that you are getting wrong in writing are not your fault: you have been badly advised. You have been taught superstitions about English that have no foundation in the language. You have been hobbled with oversimplifications. You have been subjected to bizarre diktats from supposed authorities.

Much of it was well-intentioned. Grammarians of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries lacking an established English grammar had to invent one. They turned to Latin, which had prestige and an established grammar they had been taught in schools, and they tried to adapt English to it. But Latin is a very different kind of language, and it was a bad fit.

Others have sought to tidy up the language by inventing and enforcing distinctions and prohibitions, seldom helpfully. (Look at the over/more than entry.)

We have wound up with what the linguist Arnold Zwicky has termed “zombie rules”: absurd rules that have no foundation in the language and which have been repeatedly exploded by linguists and better-informed grammarians, but which roam classrooms and editorial offices like the undead.

As Henry Hitchings summed the situation up in The Language Wars, “The history of prescriptions about English … is in part a history of bogus rules, superstitions, half-baked logic, groaningly unhelpful lists, baffling abstract statements, false classifications, contemptuous insiderism and educational malfeasance.”

Likewise, advice on writing in general is marred by oversimplifications, half-heard advice, and idiosyncratic preferences—sometimes bizarre—passed off as professionalism.

Your teachers, editors, mentors, and supervisors have a lot to answer for.

And you have much to unlearn. Look inside and see.

I have kept the advice succinct. If you need further explanation on any point, look me up. If you want to argue with me, you can try.

In the same way, many of the things that you are getting wrong in writing are not your fault: you have been badly advised. You have been taught superstitions about English that have no foundation in the language. You have been hobbled with oversimplifications. You have been subjected to bizarre diktats from supposed authorities.

Much of it was well-intentioned. Grammarians of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries lacking an established English grammar had to invent one. They turned to Latin, which had prestige and an established grammar they had been taught in schools, and they tried to adapt English to it. But Latin is a very different kind of language, and it was a bad fit.

Others have sought to tidy up the language by inventing and enforcing distinctions and prohibitions, seldom helpfully. (Look at the over/more than entry.)

We have wound up with what the linguist Arnold Zwicky has termed “zombie rules”: absurd rules that have no foundation in the language and which have been repeatedly exploded by linguists and better-informed grammarians, but which roam classrooms and editorial offices like the undead.

As Henry Hitchings summed the situation up in The Language Wars, “The history of prescriptions about English … is in part a history of bogus rules, superstitions, half-baked logic, groaningly unhelpful lists, baffling abstract statements, false classifications, contemptuous insiderism and educational malfeasance.”

Likewise, advice on writing in general is marred by oversimplifications, half-heard advice, and idiosyncratic preferences—sometimes bizarre—passed off as professionalism.

Your teachers, editors, mentors, and supervisors have a lot to answer for.

And you have much to unlearn. Look inside and see.

I have kept the advice succinct. If you need further explanation on any point, look me up. If you want to argue with me, you can try.