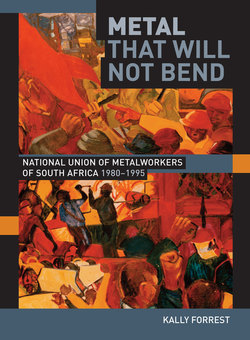

Metal that Will not Bend

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Kally Forrest. Metal that Will not Bend

Contents

Acknowledgements

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

Introduction

Chapter One. Building local power: 1970s

The 1970s: new light

Independent: Metal and Allied Workers Union

Tucsa dissidents: Numarwosa, UAW, WPMawu, Eawu

In Tucsa: Motor Industry Combined Workers Union

Unity and organisational space

Chapter Two. Power through numbers: 1980–1985

Mawu and migrant workers

Exploiting Wiehahn laws

To register or not

Growth and organisation

Shop stewards councils emerge

Education and union growth

Chapter Three. Power in unity: 1980–1987

National auto union

National metal union

Coming of age

Chapter Four. Breaking the apartheid mould: 1980–1982

The great strike: Volkswagen 1980

Pension strike wave

East Rand strike wave

Turning point

Pyrrhic victory?

Chapter Five. Worker action fans out: 1980–1984

Auto expansion

Expansion in metal engineering

Expansion into northern Natal

Eastern Transvaal setback

Expansion into Brits

Moving into homelands

Chapter Six. Melding institutional, campaign and bureaucratic power: 1983–1990

Outgrowing capacity

Early demands

Alliances for a living wage

Power through all-level bargaining

Building bureaucratic power

Chapter Seven. Conquest of Metal Industrial Council: 1987–1988

1988: Seizing council power

Build up to industry strike

National company councils

The 1988 strike

Chapter Eight. Auto workers take power: 1982–1989

Living wage in assembly

Numsa 1987: power in auto

Mercedes strike: 1987

Restructuring bargaining 1988–1989

One bargaining platform, one union

National bargaining forum

Chapter Nine. Auto takes on the industry: 1990–1992

Progress and revolt: 1990

NBF bargaining, 1990: non-wage successes

Revolt at Mercedes

Wages and retrenchment 1991–1992

Employers reassert control

Chapter Ten. New directions: 1988–1991

War at plants

Developing alternative vision

Union think-tanks

Chapter Eleven. Defeat of Mawu strategy: 1990–1992

Shifting bargaining agenda: 1990–1992

1992: year of promise and disaster

The strike fallout

Chapter Twelve. Towards a new industry: 1993

Debating restructuring

Training for transformation

New bargaining programme

Chapter Thirteen. The Cinderella sector: 1983–1990

Background to motor sector

The great deadlock

Breaking the deadlock

Chapter Fourteen. Applying vision in auto and motor: 1990–1995

Negotiating change in motor

Bargaining change in auto: 1993

Bargaining change in 1994

Negotiating change in 1995

Dangers for workers

Chapter Fifteen. Applying vision in engineering: 1994–1995

Leadership and organisational weakness

Democratising the workplace

Return to workers’ control

Missed opportunity

Chapter Sixteen. Independent worker movement: 1980–1986

Sticky question of alliances

British Leyland strike

Debating alliances

Pursuing independent politics

Chapter Seventeen. Beginnings of alliance politics: 1984–1986

Divisions in Mawu

Forging alliances: 1984 stayaway

Uneven political responses

Transitional politics

Chapter Eighteen. Weakening the socialist impulse; civil war in Natal: 1987–1994

Uneasy truce: Fosatu and Inkatha

BTR Sarmcol: the trigger

Unionists under attack

Workers and communities divided

Union response to violence

Union culpability?

Chapter Nineteen. Civil war in Transvaal: 1989–1994

Numsa targeted

Peace initiatives

Unitary vision breaks up

Lack of unified vision

Chapter Twenty. New politics: 1987–1990

Freedom Charter: contested terrain

Contestation and consensus: 1986–1989

Politics of campaigns

LRA campaign

Chapter Twenty-One. Disinvestment: pragmatic politics 1985–1989

Negotiating disinvestment

Disinvestment: bargaining weapon

Chapter Twenty-Two. Compromising on socialism: Legacy of the Alliance 1989–1995

Forging alliances

Maxwell Xulu: independent Marxist?

Alliance: complex proposition

Inserting worker perspective

Shaping economic reform

Influencing policy: reconstruction accord

A vision diluted

Conclusion

Theories of trade union power

Notes

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Index. A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

X

Y

Z

Отрывок из книги

METAL THAT WILL NOT BEND

National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa 1980–1995

.....

Numarwosa first decided to approach Africans in late 1972, while it was still in Tucsa. To circumvent the law, it used the tactical device of forming UAW as a parallel to the white and coloured unions which were covered by industrial relations laws, but with amalgamation into one union as the long-term aim. In Tucsa, parallel coloured and African union leaders were appointed by the white union executive and they were neither developed nor encouraged as trade unionists. In a break from this practice, UAW’s members elected leaders to an independent executive and sat with Numarwosa on a joint advisory committee.47 It is not often acknowledged that the independent UTP (Urban Training Project) associated with Tucsa also played a role in UAW’s early formation. Numarwosa and UTP assisted in the launch of UAW, and in 1975 UTP helped to establish a Pretoria branch and trained Dorah Nowatha to become an organiser. A UTP organiser, Michael Faya, became UAW’s first national secretary in 1974.48

UAW struggled to survive in its early years and organising Africans was a slow and secretive business. Workers were fearful, and union resources meagre. Yet beneath Africans’ cautious facade lay long-standing grievances, particularly around racial discrimination and unfair dismissal. The foremen’s sweeping powers included granting leave, giving permission to use toilets and decisions on wage increases, retrenchments and dismissals. An industrial relations director at General Motors joked: ‘The biggest optimist in the workforce was the guy who brought his sandwiches to work, because he had no assurance that he’d still be there at lunch time.’49 Formal complaints and appeal procedures were unheard of.

.....