Читать книгу Ministers of Fire - Mark Harril Saunders - Страница 1

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSwallow Press

An imprint of Ohio University Press

Athens, Ohio 45701

www.ohioswallow.com

© 2012 by Mark Harril Saunders

All rights reserved

To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Swallow Press / Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax).

Printed in the United States of America

Swallow Press / Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper ƒ ™

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

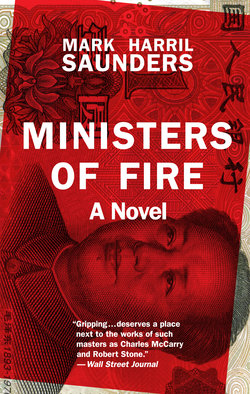

Saunders, Mark Harril.

Ministers of fire : a novel / Mark Harril Saunders.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-8040-1140-2 (hc : acid-free paper) — ISBN 978-0-8040-4048-8 (electronic)

1. International relations—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3619.A8248M56 2012

813'.6—dc23

2011053333

R.A.S.

In love we are incapable of honor—the courageous act is no more than playing a part to an audience of two.

—Graham Greene, The Quiet American

prologue

When april was gone, disappeared into the center of the world, her voice in his head would still insist that he had planned everything—not just the night in Samarkand but all that surrounded it. It was in the Burling character, she said, using his name as she did in the third person, to engineer things according to his own mind, to will them into existence while keeping his distance at the same time. The problem, Burling thought, was people. He was never any good with them. Whether that failure was due to a flaw in his makeup, or just a hedge in case things went to hell, April—the tall, abundant woman with the narrowing gaze that seemed to hide a sly yearning that Burling, in the short time given them, had not been able to fulfill—never had a chance to tell him.

February 14, 1979: to this day no one marks it as significant. November 9, 1989, September 11, 2001, but not the last troubled months of the seventies, when the world we know was born. On that Wednesday, Wes Godwin, survivor of the Philippines, Korea, and the Ia Drang Valley in Vietnam, left the Embassy Residence in Kabul by the rear gate to attend a practice of the Afghan national basketball team, of which April’s husband, Jack, was coach. Lucius Burling, deputy chief of mission and the Agency station chief, rode with Ambassador Godwin in his dusty black car. Plush seats, smell of cigarette smoke, milky sun smeared across the glass. Their route took them through an unpaved lane along walls the color of sand, punctuated at intervals by ancient wooden doors that opened onto courtyards shaded by fruit trees, where dark-eyed children with café-au-lait faces played solemnly in the dust. Burling had been a starting forward at Princeton, at a time when that meant something, but in retrospect he had to admit that his success at basketball had more to do with his natural size and a determined drive than with any great skill as an athlete. Slow-footed but strong, Burling would wait for the quick ones to feed him the ball, then lower his head, make a halting feint one way or the other, and take it to the hole.

Bull, they called him, which was ridiculous and probably in fun.

“More like Ferdinand,” Amelia had teased him.

“I worked harder than they did, that’s all,” Burling said, a bit stung. At that time in their courtship, he was still getting used to her and couldn’t really tell if her tone was affectionate or cutting.

“It’s your big blond head, darling,” Amelia said, reaching up to touch his hair, “with all those big thoughts inside it. The thinking man’s bull.”

He was not much interested in basketball now, not in the kind they had going at home, anyway. He had taken his son to see Georgetown play, but John Thompson’s game had not appealed to him, partly because he knew he wouldn’t have lasted a season in that frenetic kind of scheme. The game in Kabul was not for him either, but some of Jack’s players had ties to the northern tribes, and Burling had a plan to go up there that was lately gaining traction at Langley.

“Going through with this, are you?” Godwin said, face still turned to the world outside the car. At noon the alley was deserted except for a street dog that lapped at the gutter and perked up warily at the sound of the Cadillac, springs complaining as it shouldered through the ruts.

“I don’t look at it that way,” Burling told him.

The ambassador faced him, lips the color of bricks. He still wore his white hair in a military cut, in spite of his civilian appointment.

“We need friends up there,” Burling said.

“He-ell.” Godwin drew two syllables out of the word. “The tribes aren’t anyone’s ‘friend.’ They know Taraki is weak and the Russians are just waiting for an excuse to come across.”

Burling watched him quietly, acknowledging the obvious. Godwin was southern military royalty and therefore, in Burling’s estimation, lacked nuance in the extreme.

“You’re not thinking far enough ahead, Lucius. What about the Chinese? You don’t think they aren’t already in there? Deng Xiaoping’s got his own Moslem problem, and this is his backyard. Mark my words, this’ll blow back, maybe not tomorrow, maybe not for twenty years.”

“By then I hope we’re all in a better place,” Burling said.

The Cadillac reached a crossing ten blocks from the compound. Across the intersection, wires hung from a rusted box mounted on a pole. The place seemed unnaturally quiet under the white sky, and Burling had a vague foreboding, like waking in the morning and not remembering what you’d done—something not in your character, apparently—the night before. Perhaps it was just a case of misplaced respect for a superior. Godwin was only ten years his senior, but the Second World War made the space between them feel wider. In spite of the ambassador’s greater experience, Burling was convinced that he, the younger man, was right.

“How’s your bride feeling?” Godwin asked.

“Better, thanks.”

The ambassador rearranged himself uncomfortably and chuckled deep in his chest. “Some women aren’t made for this life. Doesn’t appeal to them.”

Burling’s heart had begun to flutter. He was aware that he was about to reveal more than he should. “Sometimes I think I wasn’t meant to be married, Wes. I seem to enjoy isolation more than . . .” Lately Burling had begun to leave sentences undone, as if his own thoughts could be read aloud. The habit worried him. “More than the alternative, I guess. At one time Amelia thought she wanted this.”

“Women are changeable. Worst mistake you can make is try to stand in their way.”

“You take Jack’s wife,” Burling began.

Godwin laughed aloud. “No, you take her, man. Too much trouble for me.”

Burling smiled involuntarily, and a deep flush came to his face. Two nights before, in the Residence garden after drinking red wine at a dinner, he had done just that. Or not taken her, exactly, in the way that Godwin meant. The logistics of that he could not imagine. But he had kissed her, surprising himself if not, apparently, April. At first he had stammered an apology, but she had smiled at him as if he were a boy, then kissed him back, one palm placed tenderly against his chest. He couldn’t tell if she was stroking him or pushing him away, and he was trembling slightly as she drew toward him, lips parting on his; he could feel the cleft of her lower back beneath his hand.

“It’s almost as if this country makes sense to her,” he said.

Godwin’s face compressed in a wolfish expression, concentrated around the eyes. A lot of things seemed clear to April, dimensions of how people lived in the world that for Burling were surrounded by a haze of uncertainty. That seemingly amused capacity for taking things as they came was what had drawn him to her. And he was, he realized now, deeply attracted, on a level and in a way that had been working in him since she and Jack had arrived in Afghanistan more than a year ago. “She’s a hippie anthropologist, Lucius. The Wretched of the Earth, all that. I’ve seen her type before in Vietnam. Comes over for the soft stuff, but what she really wants is to get in the shit.”

The prospect thrilled and terrified him.

“You should take her up north, Lucius. Involve her in your little scheme. She’s the one who speaks the languages.”

A sound like a rock hitting glass caused both men to strain forward into the deep space between the seats. A star had formed on the windshield, and Godwin’s driver—a thin, graceful Afghan with delicate fingers that could palm a basketball—slumped against the wheel. Slowly, with a smooth motion, the car rolled across the intersection, and its hood rose up, the radiator exploding behind it, emitting a wicked hiss of steam.

“Holy shit,” Godwin said, sounding deeply perturbed.

Men in police uniforms were grabbing at the handles, and Burling fumbled with the strap of white vinyl on his own door, fighting to keep it shut. Behind him they pulled Wes Godwin from the car. Burling heard the singsong of Pashto or Dari—he couldn’t tell which. The man at his window was gone, and he whipped around, expecting a blow from behind. Through the opposite door he could see Godwin’s midsection, the starched white shirt and navy tie too short on his belly, his naked arms grappling with the men. His sleeves were rolled at the cuffs, and his hands tried to keep his assailants away from him, bobbing like a fighter, grasping at anything. The street outside was bright.

“We’re going to the Serena,” one said in heavily accented English, referring to the Kabul Hotel. “You are going to give us the mujahedin.”

“We’re not going anywhere,” Godwin told them, breathing hard now, still fighting. “We’re not holding any soldiers of God.”

“Wes,” said Burling. “It’s a kidnapping, an exchange.”

“Hell with that.” Bullets began to hit the car again.

In spite of his position, Lucius Burling was a peaceful man. An intelligence analyst, not an ex-soldier like Godwin, or Jack Lindstrom, spoiling for a fight. He had come to this country, as he had more than a dozen years before to Vietnam, to assess the situation and to offer help, a way forward. A man had a few things to lean on or comfort him in life, and the integrity of this position was one of Burling’s.

“Get down, Wes!”

Burling ducked, and the back window shattered. One of the kidnappers’ bodies was flung against the trunk. Automatic fire came from three sides, and the men dressed as police crouched down and returned it with pistols and shotguns. Burling began to crawl across the seat, intending to pull Wes to safety. He was unprepared for how loud the firing was at close range. The man who had struggled with Godwin was hit in the back and thrown against the tufted leather of the door, his chest ripped open like a suitcase.

Wes was unprotected now. Burling watched him trying to push the dead man off his legs, but he couldn’t do it without leaving cover. Godwin turned a quarter of the way toward Burling; his shirt bloomed red, and he fell on his side across the seat. Burling’s ears were plugged. The rattle of gunfire sounded far away. A bearded face in a keffiyeh appeared in the space where the windshield had been. Burling thought briefly of Amelia, and a great, lonely sadness overwhelmed him. That he would die now, could die, with so much silence and distance between them. I really didn’t know this could happen, he thought.

Wes Godwin’s life left his body in a spasm.

Burling swallowed and his hearing returned to him, like a train approaching from far away. The broken car was running with a tick, then a rasp. He closed his eyes to squeeze out the water. When his vision cleared he realized that he was alone.

in the days after the killing, the organism of the city broke down and its hungers were exposed. Kabul came under siege. The city lay in a pale bowl of light, and every movement seemed magnified. April insisted it was a troop of Jack’s basketball players who attacked the compound wall one windy, hot afternoon, but Lindstrom said they’d disappeared.

“Gone up north to fight the Russians, just like they told me they would.”

Jack was sitting in the garden late that night as Burling returned from his office to the Residence, where all remaining personnel had retreated in precaution. Lindstrom spoke up as Burling approached, answering an unasked question from the darkness of the overhanging branches above a bench.

“They killed the American ambassador,” Burling said, “so they ran.”

From the tip of a brass pipe the shape of a cigarette, an ember glowed in front of Lindstrom’s face. “Keeping you up, is it?”

“I’m the guy that’s left behind.”

“Me, too,” Lindstrom said, exhaling a plume of blue smoke. He stood up slowly, a head shorter than Burling but possessed of a taut strength, like a wrestler. Burling saw that he was wearing a sidearm, as if in the aftermath of the attack he had returned to his former life as a marine. He peered up into Burling’s face. “You know what I’m talking about?”

Burling took a step backward on the uneven path. “I need to get back to Amelia.”

“The mujas didn’t kill Wes, your buddies in the government did.”

“I was there, Jack.”

“Then you should have seen it for what it was: a cluster fuck.”

“The mujahedin wanted to grab Godwin. Taraki’s people tried to stop it and shot him by mistake.”

“You don’t wonder how the government forces knew what was about to go down?”

“I wonder about a lot of things. Apparently you have a theory about this one?”

“It’s just stoned thinking, Lucius. You go on back now. Tonight might be your last chance for a while.”

Burling stared uncomprehendingly at him in the dark. Strangely, there was no sound of birds or bugs here at night. The dry air was luminous and still. Far away he heard the pop of gunfire. “Why, what’s happening tomorrow?”

“I’m a married man, too,” Lindstrom said, “so I know how it goes. The mysterious rhythms.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Man, you really don’t, do you? You don’t keep track of that shit at all.”

From an open window of the Residence came the sound of a television, the volume unnaturally loud. An American newsman was talking about hostages. “What are you smoking in that thing?” Burling asked.

“Thai stick. Grass soaked in opium. Very mellow, but I wouldn’t recommend it if you want to make love to your wife.”

Burling tried to hide his astonishment, but the effort made him seem prim. Lindstrom’s vaguely Asiatic eyes held two counterimages of the match, like tiny blazing question marks, as he lit the pipe again.

“We’ve been married for twenty years,” Burling told him. For some reason, the contemplative menace in Lindstrom’s face made Burling want to reach out to him. Or maybe, he thought, it’s because we have April in common. “There’s just not the urgency now.”

“Between the two of you, no.”

“What’s happening tomorrow, Jack? I really want to hear.”

“Half of the staff won’t show up,” Lindstrom told him, squinting as he waved the smoke away with his hand. “The masons you ordered from north of the city won’t come to fix the wall.”

“Your players told you this?”

“A month ago or more.”

“And you neglected to pass it on.”

“You didn’t want to hear it. You were so sure you had this thing nailed.”

A sound of boots on gravel startled them, and a flashlight raked the wall behind the trees: the duty marine checking the perimeter at the beginning of his watch. Above the wall the sky was a dirty yellow from the streetlights that hadn’t been shot out. “So you wouldn’t let April ride in the car with us that day. You made her come to the gym with you and said it was because she was going to show your players her jump shot.”

“I wasn’t joking,” Lindstrom said, but Burling thought he sounded evasive, in the way of a petty informer. “They didn’t think a woman could do it. I said, how do you think she got a scholarship to Georgetown?”

Jack’s pride in his wife was affecting, but it made Burling wonder what still existed between them. “What would make you think they’d understand a thing like that,” he asked, envy stirring, “when you see the women here?”

“You don’t give them any credit, Lucius, that’s your problem. All they wanted was to get their people back, the ones Taraki was torturing.”

“Why won’t the masons come tomorrow, Jack?”

“Because they’ve gone off to fight, man, just like they have since the British—shit, since Genghis Khan was here. If they don’t show up tomorrow, that’ll be our signal to get the hell out.”

the morning after, jack proved to be right. the masons didn’t come, and by afternoon the rats had chewed a tunnel through the wall from the open sewer running outside. Burling and two marines tried to patch it with a rotting bag of mortar they found in a shed, but the rats seemed to like it—for the salt—and made the hole larger than before. Like the siege of Krishnapur, no one in the embassy cared anymore—except Burling.

In the three days it took to get dependents out, he worked with a calm insistence, as if he’d been waiting for this all his life. He felt vaguely guilty at how much he relished it, and how much the work left room for nothing else.

Late on Friday afternoon he left Godwin’s office, which he had taken over, to bring his wife the news. He had kept his own family here while others got out because that only seemed right; now it was their turn. The gift of what Amelia wanted, to leave him, he bore sadly through the Residence gate. The sun was sharp from the west, and marines had taken up positions around the ornamental garden where he had kissed April, then learned that her husband had been perfectly willing to let him be kidnapped or killed. Crossing that threshold, breaking into their lives, had set something real and true in motion inside him. He had begun to believe that he was meant to understand things, about women, about the whirl of borders where he had been sent in his country’s service. He saw more clearly the factions involved in Godwin’s murder, the role of the northern tribes, even the future as it involved the United States, its enemies and allies, perhaps a Third Force, and how these things fit together in the puzzle of nations. Kissing April had even allowed him to set aside his anger at his wife, given him the distance he needed to treat Amelia with compassion, as he should. But even as he thought fondly of pleasing her, longing, hard as a stone, rose up in his throat. It’s all turned around, he thought. I actually want her to go.

Burling found his wife and son on the path near where Lindstrom had predicted the future. Jack had the information, all right, because that was his role, but Burling was meant to parse it, to understand. Godwin’s death, his plan to work with the mujahedin, seemed ordained.

“Mom killed it,” Luke said. They were huddling above a lank brown body, its coarse hair matted with blood. The boy was twelve, and his round eyes and freckled face couldn’t decide whether to be impressed or horrified. He hadn’t known his mother, a savior of birds, would beat a rat to death with a shovel.

“I am finished,” she said.

Her voice seemed unstable, and Burling wondered if she’d been drinking. He could smell something strong but not quite sweet in the air, pungent and headier than alcohol. Then it came to him: the smell of Godwin’s car.

“I know,” he said to his wife. He felt mourning coming on, prematurely: the strength it took to hold up against it steadied him. Being a man entailed equal measures of risk and resignation. He touched her on the shoulder. “It’s all pretty horrible, but you’ll be out of here tomorrow.”

“You’re not coming with us,” she said.

“I can’t, Amie.”

“You don’t want to.”

“We’re going home?” Luke asked, disappointed.

“I am done,” Amelia said.

later that night he was back in the embassy, arranging the journey up north. Sleeves rolled up past his elbows, blue pencil touching the map. Godwin’s office smelled of rugs, books, and furniture polish. The pool of light from the desk lamp ringed a pleasurable solitude. Amelia had changed, or misrepresented herself, while he had simply stayed the same. What had been an adventure when they married, what had drawn her to him, she despised in him now. His sense of purpose was a burden. That was why he’d turned to April. It was not what he had wanted, but he would have to take it on.

“Burling.”

It was as if he had fallen into the map: he wasn’t sure how much time had passed. April, dressed in a white djellabah, was leaning inside the door.

“I’m sorry, but I just can’t call you Lucius,” she said, seeing the look on his face. To his surprise, her presence was unwelcome. “It doesn’t fit you somehow.”

“It was my father’s name,” said Burling.

“Where I’m from they’d call you Junior. Something else if you were black.”

No other person in the embassy would dare to affect native dress, but April wore it as a provocation. Like her languages, the robe was almost a weapon, or a camouflage. Inside the open neckline, he could see the low swell of her breast.

“I haven’t seen you since . . . ,” she began, then immediately laughed at herself, collapsing slightly to one side so that her knuckles bore her weight on the credenza. A deceptively strong woman, she tossed her fine blond curtain of hair behind her shoulders, as if its luxuriance annoyed her. Not exactly beautiful, Burling observed. Amelia would have turned more heads at the Chestnut Hill parties where she and Burling had come of age. April’s eyes were a bit too light, the skin across her wide cheekbones sprinkled in places with the pockmarks of a childhood disease. But her neck led gracefully into her muscular shoulders and long, slender arms, wrists cuffed with tight bracelets; and her breasts, while substantial, looked firm. His father could have drawn her in three or four finely arcing strokes, his pencil describing a long thigh and hip, a cheekbone on the opposite side and above, perhaps the hair and slender shoulder to bring the composition into balance. From her waist to her toes, which were painted and bare, she was perfect. Irritation at her presence dissolved into something warmer, desire.

“You meant since Wes was killed.”

“That’s what I was talking about, yes,” she said, coming around to his side of the desk where he could see her whole length. The djellabah rippled across the space between her thighs. “But you were thinking of kissing me in the garden.”

Burling’s words caught deep in his throat. “I can’t stop thinking about it, to be honest.”

“You’re a good man, Lucius Burling,” she said. “One kiss is not that big a deal.”

“Since Wes died, things are not . . . No, I don’t want to put it on that.”

April turned and went to the tray on the windowsill, where a cut-glass bottle of arak, a pitcher of water and glasses, shared space with Burling’s African violets and creeping philodendron. “You brought your tray in here,” she observed.

Weary with lust, Burling rose. “My plants,” he said.

“You’re funny.”

“I’ve kept them alive for a long time,” he told her, picking up the long tendrils of the philodendron in his hands and rubbing his thumb on a waxy leaf.

“Most men don’t keep plants.”

“These are easy to care for.”

April poured them each a measure of the clear liquor. Adding water clouded the liquid to the color of milk. A smell of licorice rose from the glasses.

“My father raised vegetables,” she told him. “He would make them come up out of the ground like a sorcerer. Rocky ground it was, too, but fertile just the same.”

“Did you and Jack have a garden in Berkeley?”

She laughed, somewhat ruefully, and handed him a glass. “Jack is more like one of those bitter weeds that grow out of the cracks in a sidewalk. You have to respect his kind of strength. Hack him down, he just keeps growing back.”

“How did you meet?”

April sighed and lowered herself on the long leather couch, and Burling stood above her, tentatively drinking. “When I entered the program at Cal, I felt very detached. All the other kids were privileged, very stoned and theoretical. I went down to a gym in Oakland to see if I could teach the girls from the neighborhood basketball. And there was Jack, just back from his first tour. His grandfather’s mission had funded the gym.”

“I just realized,” Burling said, feeling his height and sitting down on an ottoman. Their knees were almost touching.

“What did you realize?”

“That I don’t want to talk about Jack.”

April smiled, which narrowed her eyes. “We’re not going to make it here, you know,” she said, watching for his reaction over the rim of the glass, “in Godwin’s office.”

“Was that supposed to be on the agenda tonight?”

“I’m probably not even your type,” she said, bringing the glass again to her lips. They were plump, of a rare shade of pink, defined by clean lines against her pale skin. He thought again how they had felt against his, the slight pressure receiving him, and the hardness of her teeth inside.

He had to take in breath to gather himself. “Why do women always say that to me?”

“That we’re not your type?”

“Yes, but why?”

“Because under most circumstances, you wouldn’t even look at a girl like me.”

“I would find it impossible not to.”

“That’s sweet, and I know you’re not lying, right this minute, but if I had come to your office, the summer I interned at State, you wouldn’t have been any more than polite.”

Burling took a quick gulp of the arak to steady himself. She wouldn’t have found him at the Department of State, of course, but she would certainly be aware of that. Jack would not have been reticent on that score. “Why do you think so?”

“Because you’re a sophisticated man. Worldly. Handsome, but not so good looking that people wonder.”

“No?”

She smiled to acknowledge his feigned disappointment. “You move like you played a sport, football or basketball, maybe had an injury or two, but you’re careful so as not to hurt anyone smaller than you. You went to private schools, and you’re probably rich, or at least well off compared to most people, and now you’re being groomed for one of the top political appointments—deputy national security advisor, or number two at CIA.”

“Shhh,” said Burling, pointing at the ceiling where the microphones would be. Taraki’s government had the benefit of Soviet security expertise. “Who says that?”

“Jack. Besides, you married a debutante.”

“Not quite,” Burling said. “When I met her, Amelia was rebelling against being a society girl. Drinking and going to jazz concerts with men. It’s her money, by the way. My family lost ours long ago.”

“What luxury!” said April. “To reject what others want more than anything.”

“What do people want? Amelia and I are about as conventional as can be. The problem is what goes on in my head. I tend to disappoint people.”

“Are you going to disappoint me?” April asked, pointing to his nearly empty glass.

“I’ll have one more, if that’s what you mean,” he said, draining it.

April got up. She seemed somewhat hardened now, yet still he couldn’t help feeling encouraged. When he envisioned the journey up north, she was already with him in his mind. Up to Samarkand, over the Pass. Translating Dari and Pashto and whatever else they ran across. It was probably a very bad idea to take a woman, but he was making up reasons that it had to be done for the sake of the mission, and he had already begun to believe them.

“I need you to stay with me,” he said.

She looked at him over her shoulder, half-angrily, half-wanting. At least that was what he hoped. “I already told you, I can’t do that.” She said it softly, as if to the glasses she was filling.

“That’s not what I meant,” Burling said, accepting the fresh drink. They stood close, their glasses resting against each other in salute. “When the charter flight leaves tomorrow, I need you to stay. Come over here.”

“Be careful,” she warned. “Jack is probably out in the garden right now. He’s getting high again, and when he does that he likes to talk to the marines.”

“That’s why I can’t take him with me,” he said, setting down his glass on the corner of the desk, “even though he knows the terrain.” On a yellow legal pad, he wrote, I have to go up North, to Mazar-i-Sharif, to talk to the mujahedin. “Things are happening faster than I thought, and I need someone with languages.”

“I came out here to help with girls’ education,” she said, sounding slightly desperate now. “Just because I speak Dari doesn’t mean I understand what these men are up to. And I don’t care what Jack says, killing Godwin didn’t make any sense.”

“Oh, yes, it did,” Burling said, sampling the new, stronger, mixture. “Ever heard of Franz Ferdinand?”

“That’s another problem. I’m not as smart as you are.”

“Now you’re patronizing me,” Burling said. “You know what I think?”

April raised her eyebrows. “I wish I did.”

“You’re perfect for this.”

sunday morning, burling’s family left, boarding the DC-3. Only Luke, young and game enough still for the flight on an airplane to excite him, looked back across his shoulder at his father. Amelia stared resolutely at the seatback in front of her, and their daughter Elizabeth already had her nose in a book about Emily Dickinson. Jack Lindstrom sat in front of them, “headed for an epic druggie meltdown in the States,” as April put it.

As the plane took off, leaving a trail of oddly black exhaust, and tilted across the mountains to the east, Burling thought about his children. Another secret thing he cherished was a potent love for Betsy and Luke, but he had probably lost them, too, if he had ever really had them. They were beautiful, but he had thrown off the delicate balance of that beauty through his failure with their mother. It made what he was about to do all the more important, so that someday they would understand, and the pieces could be put back together into a larger, more beautiful whole.

That afternoon he took April on a different kind of plane, a light Cessna of the type they had used in Vietnam. Its spartan cabin shook as the engines choked to life. In the front seats rode the pilot and a young Afghan man named Abdul Hadi who worked as a liaison to the government, but was run as an asset by Burling. In the narrow seats aft, pushed together by the tapering fuselage, sat April and Burling. As the Cessna climbed above the mountains to the north, April smiled at him quickly from behind her shining hair. She wanted to be a part of his world, but what did he want from her? In his office, sharing the arak, he hadn’t kissed her again, but the possibility had hung between them like a strong magnetic field. It crackled there now, at the margins. The hard stuff—as Godwin had called it—excited her. He knew that he was taking advantage of that, and yet he didn’t, couldn’t seem to, stop himself.

“On the way back—” Burling was talking above the engines to the pilot, pointing his finger at the windshield—“we may have to get in down there.”

A spine of dry, trackless hills hunched up before them, and the pilot nodded, taking a drink from a flask and offering it to Burling, who politely refused it.

“Is this where the ones who killed Godwin went?” April asked.

Abdul Hadi turned to look at her. He was uncomfortable with her presence, and Burling felt it as a judgment on him. The Afghan might be on his payroll, but where Abdul’s ultimate loyalties lay—to the Americans, Taraki, or his clan—was definitely a matter of concern. “She’s merely cover,” Burling had told him. “When we get to Samarkand, she’ll be my wife.”

“Hey, Lucius,” said the pilot, cocking his head to one side. They looked down at the pocked, ochre dirt.

“Mines,” said Burling, nodding. The plane’s feathery shadow blew across the expanse. “That’s the Soviet border down there.”

in samarkand, the minarets were silent. the madrassah with its symmetrical blue-tiled façade was empty of life. In the center of town, an old hotel faced a large, shaded square. Its lobby had the stale, dour feeling of a place for English travelers on the Continent; the old British ladies who played bridge in the cool dusty corner by the stairs seemed right at home. On the roof was a terrace strung with multicolored lights, and on the night following their arrival, Burling boarded the creaky old lift with April, to eat “en plein air,” as he said. He had dressed in khakis and his white linen shirt, as if playing the part of a colonial in a play. His hand spread gently across April’s back as he helped her to her chair.

Children ran through the tables while their parents sat smoking over the wreck of their meals. The night air was blue with their fetid tobacco, which smelled as strong as Jack’s dope, and the savor of herbs and roasted meat. In one corner of the roof a raggedy band sat on the edges of folding chairs, war medals flapping on their chests in time with the swing.

“Dance?” Burling said.

On the floor, the touch of their hands seemed quite harmless, refined.

“I’ve never been asked like that,” she told him when her cheek was close to his. He could feel the slight tremble returning, and he didn’t answer her for fear he would stutter, something he had struggled with as a child. “In southwest Virginia the boys don’t typically ask, they just take you.”

No one else joined them, and the old English ladies nodded their approval; their milky blue eyes tacked from April to Burling as the couple drew more closely together beneath the star-strewn globe of the sky. The ladies said they hadn’t seen a man dance like that since the Blitz, and they fixed April with watery stares that were fond and regretful. The music was flat, an uneasy rendering of the big bands that Burling used to play in the living room at home—his Washington home—in a time that seemed long ago now. The music felt wrong in this dry, spicy air. No scratch of cicadas with their manic crescendo, no scent of honeysuckle sweetening the night. So far from Amelia advancing through the soft, firefly dusk toward the picnic table, flowered apron tied loosely across her hips, leaning over to pick up plates. No Glenn Miller from the open kitchen window behind her. The arid Soviet night had an electric taste of betrayal and he and April glided through it with ease while the people talked about them in Russian and English and the keening of Dari.

“Why did you really bring me up here, Lucius Burling?”

Across the tables, the lift opened and a young Chinese man emerged. Burling knew from the sharp concentration of her eyes that April had seen him. Her body stiffened, which improved their dancing, as if she had taken the lead. Behind the younger Chinese came a short, fat man about Burling’s age, his thin hair combed across his scalp. The thought ran through Burling’s mind that he wanted to spoil this now, to save himself. Bringing the Chinese in complicated the whole thing beyond what he was able to predict.

“I’m serious,” said April. “If you brought me up here just to fuck me, that I can understand. And Jack can’t seem to do that anymore, in case you didn’t know, so I might just be up for it. But if you pretend there’s something else, if you’re just putting on a show . . .”

“I don’t know how to do this properly,” Burling told her, watching the Chinese colonel take his seat. “Even those ladies over there, watching our every move, I don’t know how people think about things like this.”

“I think you do but you like to think otherwise.”

He furrowed his brows to signal that he didn’t understand.

“I think that people like you like to tell yourselves that you don’t understand what people think about in the darkness of their minds, what they do with each other. That way you’re protected from the consequences.”

“People like me?”

“Powerful ones. You can screw up people’s lives and hide behind your ‘properly,’ your discretion.”

“You have me all wrong,” Burling told her. “I couldn’t do this without you.”

Her laugh was thrilling, and warm. “No shit, Chief.”

after dinner, he and april rode the lift to the lobby, agreeing without a word that they would not go to bed, not just yet, if that’s what they were going to do. The old elevator jerked downward, and the drop in Burling’s stomach disoriented him: along with the possibility that he would sleep with April tonight came the thought that his rush to fulfill one desire might be a willed distraction from the enormity of what he was about to set in motion with the Chinese. Working with them to arm the mujahedin against the Russians was a line of attack that had only glancing support at the Agency, if it had any support at all. If Amelia found out about April, or if the deputy director hung him out to dry when the operation backfired, he would be in the wilderness for a very long time.

He and April sat close, her hip touching his thigh, on a hard wooden bench in the square, framed by short, dusty trees. A public security car trolled the streets around for black marketeers. Up the crumbling steps from the bare little park they could see the brown, implacable face of the hotel, its roof bleeding color and music into the sky.

“I wasn’t making it up, when we were dancing,” Burling said. “I don’t think you understand.”

Between her thumbs April broke a pink grapefruit she had taken from the table. The fruit smelled ripe, a bit funky, and her face was sly but reluctant in the shadows. Explain yourself, she seemed to be saying. If you can.

“The first time I saw a Viet Cong dead,” Burling told her, “it was early in the war, before the marines even landed at Da Nang.”

“Where Jack got his ‘million dollar wound,’” April said with fond sarcasm, tearing the peel.

“That was Tet. This was long before that, in the fall of ’62. We were there in an advisory capacity, helicopter support. The ARVN had killed this VC in a village outside Soc Trang, and we went up to look at him, because we’d never seen one before.”

“Like killing a cougar,” April said. She handed him a section of grapefruit, the strands of pink flesh sticking to her fingernails. “When I was a little girl all the cougars, the mountain lions, were supposed to be gone from the hills behind my father’s house, but he and my brothers swore they were there. They wanted to kill one to prove they existed.”

“Did they ever get one?”

“They never did, but that didn’t stop them from believing it. If they ever had killed one, I don’t know what they’d have done.”

The security car moved soundlessly behind the trees, a cigarette glowing inside, showing dark figures slumped against the seats. The Chinese colonel, with whom Burling was to meet next morning, came down the steps and looked this way and that.

“When Wes was murdered,” Burling ventured, “the first thing I remembered was that Viet Cong. Two of the men dressed up as police, or maybe they were police, we don’t know; anyway, they were dead, too, one of them lying there on the ground beside the car. No one had closed his eyes yet. I looked at him, and he had that same sort of meditative look, almost thoughtful, and he was terribly slender, just like the VC, and I thought again that we were in trouble, now—how’d you put it?—now that we know it exists.”

April got up an inch and sat down, the way women do to shake off a subject from themselves. Above the trees to the west the sky was the color of amber, liquid and dirty from the marketplace stalls.

“What exists, Lucius? I ask you why you brought me up here, and you tell me a story about dead Viet Cong, about the soldiers of God. You tell me it’s real. What is real?”

“Sacrifice.”

“For you? For me?”

“Love.”

“Who were the Chinese on the roof?” April asked him.

the next afternoon they took off again, the pilot flying low above the ruinous desert country to the east, shaped by wind, through the jagged peaks and chilly, verdant valleys to the landscape of rocks that was home to the mujahedin. The flat, rocky ground came up to meet them, the pink horizon rocked back and forth, and April grabbed Burling’s hand with a disarming strength that reminded him sharply of the night before. At first she had led him, for which he was grateful, but as soon as he felt her with nothing between them, all the impediments around them ringed like forces held at bay, he’d begun to believe he was truly in love. What a fool I am, he thought.

“What is it?” she asked, drawing back.

The wheels banged across the slabs of the landing strip, jolting him out of his dream. The airfield had been built by the British after the war, part of their own misadventure in this remote, empty place. The plane shimmied as the engines and brakes dragged it down, then choked to a stop before a rusting Quonset hut. A hundred yards along the tarmac sat a Chinese military plane, with a Land Rover parked beside the tail. When the pilot opened the hatch there was no sound but the wind.

A rumpled guard roused himself from his seat against the corrugated steel of the hut, scratched his new coils of beard, and dragged his rifle out to see Burling’s papers of introduction, his bona fides from Jack. Somewhere a piece of metal banged against itself.

“How did the Chinese get here?” April asked.

“Overland,” Burling said. “The borders are pretty porous up here, but they can’t fly that plane into Samarkand.”

“I don’t see them, though.”

“I know. Neither do I.”

April tried to ask the guard in her limited Dari, a language of which she was proud for the very obscurity of it, but the guard was like a man waiting for a storm: as Burling’s papers flapped before him unremarked, he kept looking at the featureless sky. Abdul Hadi climbed from the plane and watched her with dark-eyed contempt.

Where had he been last night? she wondered.

“What on earth possessed you to learn a language like Dari in the first place?” Burling asked as they waited. “Apparently even the natives don’t trust it.”

She could see that Burling was trying to place the guard.

“They didn’t tell me that at Georgetown,” April said. The guard uttered a few rusty, atonal syllables she didn’t understand. “They were more about Pashto, the language of the rulers.”

“Did he say that they were coming?”

Abdul nodded before she could open her mouth, and suddenly her irrelevance coursed through her like a shock. The guard seemed to be suppressing an emotion, although it was unclear if the twitch around his mouth was mirth or rage.

“He speaks the languages, too,” she whispered fiercely to Burling. “Apparently some that I don’t.”

“There are a lot of them,” he said, “but I don’t trust him as far as I can spit. Come on. Roy!”

He hailed the pilot and turned toward the plane, but before he took another step they had begun to hear the sound of a small band of men riding down from the hills—not a sound exactly, but a sudden disturbance in the ceaseless wall of wind, the creak that is made by tack flailing the muscles of lathering horses. The pilot, smoking by the wing of the plane, reached for the holster on his hip, but Burling made a damping motion with his hand. Shapes emerged from the brown pack until each was an individual rider and animal, bearing down across the hardpan in a clatter of hooves and drawing up, veins bulging in necks dark with sweat. April watched them with her mouth half open, her hands raised slightly from her hips as if she were about to appeal to them for something. Mercy was the word in her mind. The air had stopped in her mouth. Saliva seeped from the insides of her cheeks, but her throat was bone dry. This was the first place she had been where she knew that being American didn’t matter.

The leader, who rode a bay stallion two hands taller than the rest of the horses, dismounted in a whipping of cloth. The loose jacket of April’s suit lifted in the wind, chilling her. Her hands were plunged deep in the pockets of her pants, stretching the coarse cotton across her hips and the backs of her thighs. She had always been strong, tough; her physical qualities had served her well while making her different and hiding her mind, her emotions, from men in particular. Burling had seemed to cut through those traits: while he clearly admired her body, wanted her openly like a younger man would, he seemed genuinely moved by her manner, intrigued by her mind. He made love as she’d thought he would, carefully, restraining, controlling a massive emotional and physical force. He moved forward now, a grim smile set on his face. The wind stung April’s cheeks. Slowly, he and the leader looked each other up and down. In a moment they were shaking hands vigorously and nodding, the leader looking to his comrades and flashing his gleaming white teeth, pointing and laughing as if he’d won a bet.

“Abdul!” The leader, an uncle to Jack’s power forward, gave the man a kind of greeting that April had seen in Kabul, grasping both shoulders, shaking him. “Come.”

“You stay here with Roy and the plane,” Burling told her, sotto voce. “If you see Abdul Hadi come out of that Quonset hut without me, he may have sold us up the river.”

“What do we do then?”

His eyes met hers as if to say that no matter what happened, it had been worth it, but she wasn’t so sure. Something told her that his own romantic dream would survive, with her as only a memory.

“I want to come with you.”

“That would be more dangerous than staying here,” he said. “I’m doing this for you, believe me.”

“Burling!” the leader said heartily. “We go?”

Together they started toward the hut.

The other riders drew their mounts together, the smallest man holding the reins of the leader’s incredible horse. April shuffled back toward the wing of the plane, where the pilot was smoking a cigarette. The mujahedin—because that’s what they were, “the soldiers of God” whose names she had taken in vain the night before—were nothing like she’d expected: up close, they were scruffy and rancid, with nervous faces and intense, dark, sorrowful eyes—not mountain lions at all, but scary in the way of stray dogs, unpredictable. They reminded her of hollow boys back home.

April said a few words to them in Dari, and they replied with a slur against women. The pilot, Roy Breeden, raised his eyebrows at her.

“They say they want to rape me,” April told him, although that was not exactly what they’d said. “I think a stake may be involved.”

“Like a Joan of Arc number?” Breeden squinted through his smoke.

“I could go for that maybe, if they didn’t smell so bad.”

The pilot took a pensive drag. A scar cleaved his upper lip, and when he smiled it made his mouth look like a beak. “These boys might not take you up on it,” he said. “They’ll be fed grapes by seven thousand virgins if I shoot them right now.”

April looked at the mujahedin. Suddenly their shifty demeanor seemed more menacing than before. Lucius had used the word “sacrifice” about them, equating it with love.

“What a load of shit,” she said aloud. The horses had moved more closely together, and she couldn’t see the hard desert light between their bodies anymore. Her own bravado went brittle. This might work with the hollow boys in the gravel lot behind the high school, as the vapor lights wore out from the game, but she’d miscalculated here: she’d never been outside of Kabul. Two other riders dismounted, and for the first time she noticed the rifles lashed across the pommels—long, black, shining automatics like Jack’s own M-16. Breeden flipped his cigarette toward the nearest hoof, reached back into the plane, and casually brought out a shotgun—a twelve-gauge like her father’s—holding it as if it were as harmless as a broom. April turned to the men, who had drawn their horses back at the sight of the weapon. “I’m the closest thing to heaven they’ll ever get.”

“You’re a hell of a woman, all right,” the pilot observed. “I can’t decide if I like you or not.”

“Do you think these boys know Jack?”

“Might.”

She couldn’t tell if he was implying that knowing Jack might not be an asset right now. He held out the carved walnut stock for the men to inspect. The one who’d been holding the leader’s reins handed them up to the man beside him, who still sat his horse. Then he came forward and weighed the shotgun like an offering in his palms.

The near proximity of the dismounted men, who gave off a rank odor of horses and sweat, was causing fear, the real thing, to run through her like a current. She was guilty, she realized, not only of coming up here with Burling, but of thinking she could handle this. She had run with the boys all her life, run from her brothers straight to Jack, which had upset her mother and scandalized her graduate student friends at Berkeley, with their stoned existentialist boyfriends who didn’t care what women thought, even whipsmart scholarship girls like April Wheeling, who could drink harder and quote Jean-Paul Sartre, Lévi-Strauss, and Fanon better than they could. When Jack went off to Vietnam for the second time, April had finally realized she could want more than boys could give her, but it was hard to break their grip. Beyond the horses, she could see Lucius Burling and the leader coming back across the runway. No Abdul. What did that mean? Trailing them was the stout Chinese man she had seen on the roof of the hotel. The man who’d been holding the leader’s horse barked something at his clan, in a dialect she could barely understand. He removed a thick knife, about twelve inches long, from his garment. Fear gripped her heart when she realized what the man had said.

“Roy?”

The man on the horse trained his rifle on the pilot.

“They said we’re not leaving,” April told him.

Breeden moved his hand to the holster, but the rifle gestured him to take it away. Breeden didn’t do as he was told. She saw him unsnap the holster, and the rifle went off above her, a quick burst that cut Breeden down. He was on his knees, screaming obscenities, as the horses crowded around her. At first it made her feel safer, their bellies pressing against her, the familiar sweet, sharp smell. She had a flash of her father, his long legs in blue jeans hiked high on his backside, climbing stiffly up the hill toward his broken-backed barn, winter sun in the bare trees behind it. Then she felt herself being lifted; her feet no longer touched the ground. Through the dust she saw the knife raised above Breeden’s head.

book

one

Lindstrom’s plane picked up speed as it sliced through the clouds; below the cover, fires burned on the ground. Smoke rose from the crossing of twin brown tracks, and he saw red-brick communes surrounded by fields. The man in the seat beside him—a tall, stiff German with muttonchop sideburns and rectangular glasses that turned an odd purple shade in the sunlight—stirred at the abrupt drop in altitude and slapped himself sharply on the knees.

“Well, now, Jack,” he said, angling an elbow between Lindstrom’s ribs. The German’s use of his first name seemed vaguely insinuating, maybe even coercive. “You are coming to see me, yes?”

The plane settled after floating on a deep breath of air. The German was director of a joint venture power company in Shanghai: earlier in the flight he had invited Lindstrom to his plant, to show him how energy was revolutionizing China.

“I’d like to,” Lindstrom answered, and wondered if he would. It was his tendency to view industry with suspicion. “But I have these plans in Nanjing.”

“Right, right,” the German said heartily. “The missionary business.” He dismissed it with a chop of his hand.

The plane crossed the Yangzi River, its lumbering surface flashing bronze in the hazy spring sun. From a dock along this river, almost seventy years ago now, Lindstrom’s grandfather had embarked with other missionaries up into the gorges in Hubei for a summer retreat, the whole junket paid for by a brewer from Tsingtao. A man of obvious and violent contradictions, Lindstrom’s grandfather hadn’t had any scruples about accepting the invitation, although by that time he was temperate to the point of fanaticism. The gorges they’d visited were about to be dynamited by the German and his indigenous partners for a dam.

“I’m really not a religious man,” Lindstrom said, “but I’ve never been able to resist the possibility of revelation.”

“And that is why you are coming to China?”

“To see the church that my grandfather built.”

“This will be the occasion for your revelation.”

Lindstrom was about to reply, but explaining his motives would only draw attention to himself.

“As a businessman,” the German said, “one cannot be concerned with such things. Nevertheless, power can be—what is the word?”

“Corrupting?”

The German accepted Lindstrom’s trope with a ruthless sort of calm. The plane was cutting through frayed wisps of cloud, and the sun gave off a soiled and monotonous glare. The German’s lenses grew darker. “I’m not speaking in metaphors,” he said. “In China whoever controls the generation of power can be a force for reform. I must believe this.”

Lindstrom let the subject lie. A geopolitical discussion with a power company executive, no matter how endless the potential store of puns, would probably not be that illuminating. Since September 11, everyone possessed a theory about world historical order: doomsday philosophy was epidemic even compared with the 1960s. It rivaled the paranoid epic of the late Cold War. Outside the window, the cruciform shadow of the plane stretched and rippled across the towers and cables of a bridge. The plane moved faster above the water. The fence around the airport approached, and he experienced a pleasurable rush of fear. Beyond the concertina wire stretched a dry landscape of yellow-green grasses and flame-like trees that reminded him of Vietnam.

“You come to my plant,” the German told him as the plane jammed down on the tarmac. He sighed like a man who has just made a lot of money from some defect in human nature. “You will see.”

As the plane slowed to taxiing speed, the Chinese passengers began to get up and trip over each other in the aisle. Outside, a stairway was wheeled across the slabs. Stooping under the bulkhead, the German pulled on a corduroy blazer that had gone out of style in the seventies but was coming back in now. The new global capitalists were adopting a retrograde camouflage, several sizes too small.

Lindstrom slid from his seat and moved forward past studious men and bantering elderly couples, Taiwanese businessmen in clashing Hawaiian shirts, all silenced by the German’s unusual height. Lindstrom shadowed him, grateful for the cover. As he emerged behind the German from the hatch of the plane, heat met them like a curtain, and they flailed for a moment in the new, thicker element. Lindstrom felt himself awakening slowly in an old, familiar place, at once comfortable and frightening. Backstage again, behind the ancient drama of the East, where each person, object, strand of phrase you caught above the diminishing whistle of the engines might be trotted out for use under the great proscenium of communist government.

“You come to see us,” the German said pointedly, “when you are done with the church.”

They were hurrying now across the tarmac, through the greetings and luggage; every face they passed looked amazed. Beyond a low chain-link fence, a BMW waited, with the license plate letters signifying foreigners, followed by the regional number for Shanghai. Lindstrom felt a wave of paranoia. Behind the Bimmer was a tiny, ornamented cab.

“You’re not flying on to Shanghai?” he asked.

The German’s shaggy hair lifted in the wind. “Ever since the Chinese government deregulated the airlines, it is impossible to get a flight from Frankfurt to Shanghai. Impossible,” he yelled above the sound of a plane taking off, as if the word could explain the whole country.

the taxi was cramped, and its dashboard was covered with talismans. From the homemade bodywork, Lindstrom could tell that it was an unregulated cab. The driver squeezed them onto the road between two stinking trucks, and the diesel burned the back of his throat as the driver, playing with the knobs on the radio and steering with one hand, overtook the frontmost truck in a torrent of blue exhaust. The truck was filled with reed baskets and great chunks of Styrofoam; its pilot grimaced through the windshield at the pale disk of sun.

The road lay straight as a canal between fields. As the taxi gained momentum, moist air funneled through the windows, thinning the fumes and the odor of hot vinyl seats and painted metal. Bicycles pumping against a flickering background of trees. In the paddies, workers with pants rolled up to their knees spread floods of blue water. Lindstrom checked the pulse in his neck to gauge his excitement and found that his skin had a cold, clammy feel. The air wept huge, grimy drops on the windshield, then held the rest in.

As they neared Nanjing, the spindly poplars of the windbreak gave way to giant Himalaya trees, their peeling branches trained upward like arthritic fingers around the wires. Long strips of bark lay curled in the dust at their feet. Caustic smoke hung thickly above the city, and Lindstrom realized he had not given the driver an address. The taxi pressed into the crowd, buses and bicycles everywhere, ringing their bells. The driver turned and showed him a rictus of rotting teeth.

“Jingling,” he said. “Jingling Hotel.”

Of course, Lindstrom thought. Where else would a Westerner be going? Still, the prescience wasn’t encouraging. In Saigon, if you weren’t in uniform, the drivers would take you to where a bomb was about to go off, thinking you were a journalist, or a missionary priest. With his shaved head and quarter-Asian eyes, Lindstrom had often been mistaken for a priest.

The taxi rounded a rotary, hazy with neon. The radiating streets showed wet treads from the watering truck. On the far side, some citizens loitered, staring up through the gates at the Jingling Hotel. A recent joint venture between the Chinese and a Scandinavian hospitality chain, its slick white concrete and gray glass belonged in Helsinki. The unlicensed cabbie couldn’t pull onto its driveway, so Lindstrom gave him some yuan he had traded for in Tokyo and asked him to wait.

The lobby was filled with garment designers and Overseas Chinese. Security cameras bristled from the capitals of marble columns, and all the porters and check-in attendants had been given English names. Lindstrom held a small argument with a porter for show, then allowed the man to disappear with his suitcase while he checked in under the name on his passport, John Tan, and went up in the glass-sided elevator. Looking down on the lobby, at the double-breasted businessmen checking their watches, he thought of the lobby of the Hotel Nikko San Francisco, where his own desk sat empty now, his brass nameplate removed to the closet where the manager kept the names of all the wayward concierges who had gone out in the world to find themselves, only to return less sure of who they were but much more broke and in need of a job. Lindstrom had been on duty there, eight months ago now, listening to an Indonesian salesman explain, in the code of Asian businessmen, that he wanted a girl, when Alan Rank had appeared in the queue. At first Lindstrom hadn’t recognized him, but when they faced each other two hours later across a table in the Nikko’s sushi bar, Lindstrom had seen behind the dry tucks of skin around Rank’s eyes, through the salt-and-pepper beard, and there was the gangly kid from Flatbush whom he had known on the Batangan Peninsula more than thirty years before. When the pretty Cantonese waitress brought their drinks, Rank had already told him that he wanted Lindstrom to smuggle a dissident out of mainland China.

“Would you believe,” Rank said, holding his sake under his nose when they had consummated the deal, “that there are Americans living in China, old communists from Brooklyn like my parents, living in Beijing as citizens? Been there for fifty years.”

It wasn’t clear if Rank admired them or not.

“What do they do there?” Lindstrom asked. Suddenly the five-star Hotel Nikko, where the rehab gurus placed him years before, had begun to look like a smack bar in Saigon, all mirrors and hustlers and promised games of chance. “Are they happy?”

Rank signaled for the waitress to bring them more sake. “Happy? Why would they be happy? Everything they went there for has gone up in smoke. The girls in Beijing wear the same platform sneakers they do in New York.”

“Why do they stay, then?”

Rank looked at him strangely, slightly turning his head. “You know, you haven’t changed a bit, Jack. Not many people would ask that.”

“But I am asking. Why don’t they just go home to Brooklyn, where they can get a decent bagel, or Florida?”

“Because they have lives, Jack. Friends, a system of being.”

“Yeah, I wonder what that would be like.”

Rank watched the rising bubbles in the fish tank uncomfortably. Whenever Lindstrom tried to broach the subject of his discontent, people looked as if they needed to use the bathroom. Even the shrink the rehab gurus had sent him to had only wanted to talk about the present. All behavioral, he said. What about the past?

“There’s this British guy, Jack, I swear he looks like an overweight golden retriever. Got a crease in his forehead from an accidental discharge, says it happened on a transport in Burma. He’s the one who got in touch with me, not long after I accepted the position at the Center in Nanjing.”

Lindstrom swallowed with alacrity in spite of himself. When you didn’t have a “system of being,” you needed a rush to fill the empty space. It was not unlike going back on the spike, he thought. “You’re saying he’s Six?”

“I don’t know what that means.”

“MI-6, Alan. As in Military Intelligence. James fucking Bond. Don’t play virgin with me.”

Rank shrugged. “All I know is he likes to quote Shakespeare. Seems to think he’s Falstaff, complete with a giant chip on his shoulder for being rejected by the king.”

The flutter had quickened underneath Lindstrom’s ribs, and he took a swig from the fresh drink to quell it. “This is beautiful,” he said, looking around in the aqueous blue light of the bar. Already, it didn’t feel like home. “Spooks who’ve been privatized. I need to know more, Alan. Such as it is, I’d be giving up my life.”

Rank’s head swiveled back and his gray eyes were sharp. “In our current state of post-9/11 madness, the group feels that human rights have been buried. They feel that China is as good a place as any to bring those issues to light.”

“You might tell that to the Afghans,” Lindstrom said.

Rank looked at him quizzically. People tended to forget about April, perhaps willfully, about that chapter in his, in their country’s, collective life. Al-Qaeda had forced them to remember, and in that sense, Lindstrom felt connected to the world for the first time in years.

“Are they professional?” he asked.

“Very,” Rank said, eyes following the waitress as she lay down their sushi on black plates. On Sunday afternoons, she and Lindstrom sometimes met for dim sum and a karate movie—a sad, platonic date. “They say to be ready to go on a day’s notice, but no later than June 1. Someone, Falstaff I imagine, will be in touch.”

lindstrom’s room at the jingling was a sterile affair, looking out across the cowering town. He turned on and off all the lights and the television. At the minibar, he recorded his presence with the room service office by fixing himself a glass of Glenfiddich from an airline bottle. Trying to steady his hand, he realized too late that the ice might be bad. A small lapse of instinct, but it worried him. When his suitcase showed up—attended by Frank, Joe, and Miles—he tipped them all way too much, messed up his bedclothes, took his daypack, and went down to the street.

The driver had moved on beyond the hotel, and Lindstrom had a hard time convincing the gatekeeper that he wanted to go out unaccompanied. Then he had to fight off the black marketeers and the other gypsy cabs. His driver was reading a newspaper and drinking a Coke, and this time Lindstrom told him, “Black Cat.”

The Black Cat Lounge, Rank had said, was like one of those places—three small, thatch-covered rooms of candles, round wooden spool tables, and sweating cement—that the two men had frequented in some of the grislier localities of South Vietnam. Set up in this instance as an exercise in entrepreneurial activity by Rank’s students at the Center for Sino-American Studies, instead of MAC-V, the Black Cat was a mixture of Bangkok and Berlin, dive and cabaret, but its terminal dusk had been startled by the morning. Sharp blades of light cut from the door into the anteroom, which smelled of hemp and rain. Wandering through the requisite beads to the barroom, Lindstrom found a sole American woman in the flush of her early forties, hip on the edge of a stool, discussing a pile of receipts with a Chinese man in a soiled apron and white paper hat. As she slid off the stool, she tried to place Lindstrom’s face with a worried expression.

“I thought word had got around,” she said, slipping her fingers around the bottom of her throat. Her reddish hair was swept up to the back of her head, and the dangling earrings she wore made her neck look unnaturally long. “They shut us down. The police. This morning. For health violations.”

Lindstrom had thought she was talking about his mission, and he swallowed the lump that had risen in his throat. His view of the kitchen did not contradict the police’s decision.

“I just arrived in country today,” Lindstrom told her. “Professor Rank had said I should meet him here.”

“Then you must be his friend, Jack.” She removed her hand from its clutch around her throat and extended it formally to Lindstrom. “I’m Charlotte Brien.”

“Johnny Tan,” Lindstrom said. Her hand was chapped, but strong. “Is Alan here?”

Charlotte Brien looked unhappy for a moment, and Lindstrom wondered if standards of cleanliness were the only reason the bar had been closed. “You must know him from Vietnam,” she said, brightening. “That would explain the ‘in country.’ Alan calls those his ‘Namisms.’ I sometimes think he has too many ‘isms’ mixed together, but then I wasn’t in that terrible war.”

“Neither was Alan.”

Charlotte peered at him sharply through the dimness, like a dog catching a whiff of something bad.

“Alan was with AID,” he explained. “Hearts and minds. Development stuff.”

“I’m with public diplomacy in Shanghai,” Charlotte said.

“At the consulate?”

She nodded—somewhat bitterly, he thought.

“Then I know your boss, Burling.”

“I’m a cultural liaison. I work very little with Lucius.”

“Don’t do the hard stuff, right?”

Her green eyes flashed as the cook reached down beneath the bar.

“No, no,” Lindstrom told him, surprised that he understood English. “It’s a diplomat’s expression. Hard stuff, soft stuff. Still, a drink might be good.”

“It sure would be,” Charlotte said with resignation, feeling her way back onto the stool. She kneaded her temples, and Lindstrom wondered what exactly she was doing here. Her pallor had the desiccated look of a perpetual graduate student, and he considered the possibility that Charlotte Brien was the genuine article, someone who believed you could change a bad country from the inside. In Lindstrom, it sparked a predatory mechanism.

“Sometimes this country makes me nuts,” Charlotte said.

“Did you prefer them as Maoists, rather than—what do they call it now—‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’?”

“That’s what the Party prefers.”

The cook poured something clear from an unlabeled bottle.

“Let me ask you something, then,” Lindstrom said. Accepting the drink, the heel of his hand stuck to the polished veneer of the bar. “We can be honest because we don’t know each other well. Friends of mine back home in California are offended that the Chinese haven’t stayed true to their principles. Since the Soviet Union went down, it’s a slam dunk for capitalism, and that bothers them. For me, I’ve found that being true to your principles can be somewhat . . .”

“Disastrous?” Charlotte looked at him knowingly and held the dirty glass up to the light. “For the young people caught up in the Cultural Revolution, or the Great Leap Forward, or any of Mao’s other lousy schemes, it certainly was.”

“I was going to say self-destructive,” Lindstrom told her, putting his empty glass down on the bar. The cook refilled it immediately. It had tasted like Jameson’s. “But that’s my own lousy trip.”

To her credit, Charlotte let his candor pass. “I’m not sure I understand you.”

“To put it another way, if you stay true to yourself, does it crowd out other people?”

For a moment, Charlotte seemed uncomfortable, as if he had given her a line. Then she started to laugh. Her laugh was musical, uninhibited by scorn. “Of course not, Jack. I mean Johnny. Boy, what a guy!” The drink was warming her, clearly. Maybe even unhinging her a bit. “Which one was it again?”

The sound of her laughter warped in his head; the liquor was turning on him.

“Johnny. Johnny Tan.”

“Johnny.” Charlotte reached out, took his wrist in her hand. “Being true to your nature connects you with other people, with history. Being true to your nature makes room.”

She was smiling, but Lindstrom pulled his arm away with a sniff. The predatory reflex came back hard and strong. “How well do you know Burling, anyway?”

“Lucius has been back in D.C. for the past month,” Charlotte said. She stared at him evenly, but her hand went to her neck again, and between the pale fingers he saw a spreading blotch of red. “I think I’d better point you in the direction of Alan. He must be wondering where you are.”

“I’ll leave you then,” Lindstrom said.

“It’s okay.” She picked up on his note of apology, and he wondered if it was genuine. “It’s just the wrong time for drinking and spilling my guts.” Her unsteady hand was pointing past him toward the door. “Alan’s over at the Center.”

The wedge of light from the door stabbed his eyes, and his head began to throb. The pleasant melancholy feeling he had carried from the airport turned into self-loathing.

“I’m sorry. Sometimes I can barely stand my own company,” he said.

Charlotte smiled across the room, recovering herself. He saw that she couldn’t help listening. That, and her ease in this alien country, reminded him of April, before his suffocating presence had made her compassion turn inward and burn itself out.

“Join the club. Two years ago, this was the center of the universe. Now no one even thinks about China.”

Perched on her stool, she seemed to preside above the waters of his discontent. He needed to leave before he asked her to go to the Jingling with him.

“The entrance to the Center’s just down the alley on the left,” Charlotte told him. “You’ll come to it before you even know it.”

Lindstrom left the bar like a scene from a parallel life.

outside, the hutong was cobbled and dusty; its sand-colored walls dazzled his eyes. Above the ruin of houses, the muggy air hung like a tent, scented with a sweetness that prefigured decay. A hundred yards farther, Lindstrom found the gate to the Center and pushed his way inside.

The compound was refreshing to his eyes: green muddy lawns and walks lined with bright poppies and marigolds. He sensed a chance for renewal in the fresh, bitter smell of the garden. At one end of the grounds stood an old mission building with a red-tiled roof and walls of porous gray stone. Directly behind it a newer building loomed, and through its windows he could see young American students in sweatshirts and Nikes, in various attitudes of study.

Rank received him in a room full of overstuffed furniture, lace doilies on the arms of the couches and chairs. It had the empty formality of a funeral home. Rank came forward from the window, shrugging his shoulders in a loose-fitting khaki suit. He seemed to have aged in the three months since Lindstrom had seen him—his high, narrow forehead was creased like parchment, his beard had more gray. On his feet he wore black cloth shoes, which struck Lindstrom as an affectation.

“Sergeant,” Rank said absently. He took Lindstrom’s hand in a loose-jointed grip while he checked his friend’s body for damage. “How is it every time I see you, you look just the same, while everyone else keeps getting older?”

“It’s part of an experiment,” Lindstrom said. “The doctors want to see if certain methods of torture perfected by the Viet Cong retard progression through the normal stages of life. So far it’s been successful.”

Rank’s reaction was shy, and yet there was something smooth and practiced about him as he brushed off the joke and showed Lindstrom a chair. Rank was eerily comfortable with what Lindstrom had always taken to be a collective sort of grief. He had first noticed it in Vietnam, where Rank was nicknamed Oracle, a spiritual consultant of sorts for the recon marines. He had made them believe they were all on a pilgrimage, that the East would heal their psychic wounds and they would all go back to the world knowing a purer way to live. Rank himself was ambivalent—that was part of his draw—but after Lindstrom got home he’d started to see something vaguely unsavory about him. He’d begun to think that Rank might not be so pure after all, or that his purity had been a catalyst to violence.

“To be honest,” Rank said, sniffing reflectively, “I was a little surprised when you agreed to come.”

Lindstrom sat down heavily, peering through the curtains at the lawn. “I met your girlfriend at the bar. She reminded me a bit of my wife.”

Rank’s breath made a whistling sound, and he placed a finger under his nostrils to stay it. “You mean Charlotte? She’s not my girlfriend.”

“Well, whoever she is, you can’t tell me she doesn’t remind you of April.”

“Maybe a little bit, physically, but only in an approximate way. You’re not still on that, are you?”

“It just seemed like one of your tests, Alan, to see how human beings react.”

“I can’t arrange a woman’s physical appearance, Jack.”

“That’s not what we thought in Vietnam.”

Rank grinned, and the trimmed, white hairs of his beard parted, revealing the scar beneath his lip. Inflicted by the one grunt who had thought that Oracle was a fake, it became a sort of stigmata when the man who did it was killed the next day. “In Vietnam it was good to believe those things. It kept your mind open and your instincts sharp. But now we’re back in the world.”

“It feels more like ’Nam to me.”

Rank cocked his head and tugged at his beard.

“My instincts, by the way,” Lindstrom told him, “turned out to be better suited to a shithole like Vietnam than to anywhere else. When I got back home I tended to see things that weren’t really there. Then I willed them to be true. You look worried, Professor.”

Leaning forward, Rank parted the curtains with his fingers. Outside, the lawns were misty and dark. He sighed, and Lindstrom felt his own sense of drama overtaking events. “China is a frightened and tragic country, Jack.”

“Isn’t that why you love it so?”

Rank’s fingers bunched the lace as he gazed at the tower of the Jingling Hotel. When he looked back at Lindstrom, his expression was plaintive. “It’s not the same as Vietnam,” he said with a tremor of conviction. “Here we’re dealing with a communism that’s hardened, gotten older, the same way I gather we have.”

“You mean they don’t believe in anything at all?”

Rank let go of the curtain and settled back in his chair. He studied Lindstrom with avuncular concern. “Is that how you are, Jack?”

Lindstrom threw it off with a laugh. The room smelled of mold. “My grandfather made me believe that you couldn’t have a meaningful life unless you gave it away first to some ideal. In his case, God. I didn’t find out what bullshit that is until I lost the one thing that was good for me.”

Rank watched him evenly. On the wall above his wing chair hung a few courtly, hand-colored prints that resembled cartoons. “You’ve got to move beyond her, Jack. You’ve got to take steps.”

“Is that what you’re doing?”

Rank’s teeth shone for a moment, before he reacted to the sound of the latch. “Ah,” he said, uncrossing his legs, “here we are.”

The door to the hallway opened silently, and through it came the sounds of typing and hushed, earnest talk, the odor of a men’s room. A woman entered with a tray of porcelain cups and a large jug of tea.

“Thank you, Suki,” Rank said, rising formally. “Jack, this is my wife, Su-ki.” The second time he pronounced her name precisely, as if to emphasize his mastery of the language. “Su-ki, this is John Tan. His grandfather built the church in Anhe.”

“So this is what you mean,” Lindstrom said. As he took in her figure, the blue dragons on the teacups shook just enough to make a musical sound. Suki’s beauty made you search for it, as if you weren’t supposed to see it all at once, but once it entered Lindstrom’s mind it remained there like the sun. She made Rank look ravenous, old.

“You are pals,” she said, staring at the teacups. Her idiom made her seem fey.

“Is that what Oracle told you?”

She nodded unsurely and looked at her husband.

“Oracle is a name the men had for me in Annam,” Rank explained.

Suki took a deep breath as if about to recite. “My husband has told me that the war was a very important time for his life,” she said, looking up as she poured the tea.

Lindstrom blanched his irritation by burning his palm on the side of the cup. “It certainly had an effect on him,” he said. “Alan was observing just before you came in that your country is much different from Vietnam.”

Rank was checking the strength of his tea, and he nodded, his pendulous nose cupped by steam. It was a signal between them, and Suki turned to go.

“Many Chinese people go to Annam,” she said, backing out the door, “but their talent for business is not appreciated there. Good-bye, John. Some time I see you in the States.”

“I hope so,” Lindstrom said, but he doubted it would happen. He couldn’t imagine her in Morningside Heights, serving tea to Rank’s students, another object in the old Orientalist’s collection.