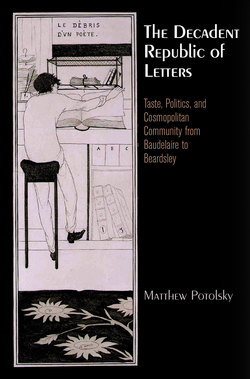

The Decadent Republic of Letters

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Matthew Potolsky. The Decadent Republic of Letters

Отрывок из книги

The Decadent Republic of Letters

Taste, Politics, and Cosmopolitan Community from Baudelaire to Beardsley

.....

Beginning with his praise of the artistic schools, Baudelaire speaks to and for a literary and artistic elite that abides within the modern world but operates according to its own laws and institutions. It is a self-selected community within the broader society, a decadent republic of letters. As Walter Benjamin recognized, Baudelaire was the first poet to understand the nature of the modern literary public; he writes “to whose who are like him.”12 Benjamin here refers to the shrinking audience for lyric poetry, but the point applies to Baudelaire’s other audiences as well. Baudelaire appeals to the aesthetic elite as “friends” and “unknown sympathizers [partisans inconnus]” (OC II, 779; PML 111), and characterizes this elite as an aristocracy. “I think,” he writes in the Salon de 1859, that “artistic affairs should only be discussed between aristocrats, and … that it is the scarcity of the elect that makes a paradise” (OC II, 633; AIP 168). Perpetually impoverished and a product of the stolid middle class, Baudelaire by no means saw himself as a part of any actually existing sociopolitical aristocracy. Rather, and in a manner that would influence the often deceptive class politics of later decadent writers (who were overwhelmingly drawn in both France and England from the provincial middle classes), he maps the traditional prerogatives of aristocratic life—its leisure, its history of artistic patronage, and, crucially, its perceived sense of responsibility for the commonweal—onto the ideal of an artistic life. The marginality of nineteenth-century artists mimics the leisure that enabled aristocrats in earlier republics to serve the public good. Creating beauty and exercising the faculty of taste are acts of civic virtue, a contribution to the betterment of the polis.

Gesturing toward the hereditary nature of aristocratic rule, Baudelaire defines his elite as a kind of family. The language of kinship, with its weight of nature and familial obligation, might seem to sit uncomfortably with Baudelaire’s civic humanist ideal, but it is in fact essential to it: artistic genius is a birthright, like aristocratic blood. Membership in Baudelaire’s elite is wholly elective, however. It is necessary yet chosen, at once natural and constructed. The language of kinship also underscores the bonds of sympathy that unite the members of the elite. They are an unnatural family, kindred spirits born into membership and bound by artistic affiliation, not by blood; the only lineage they recognize is artistic tradition, with the relationship between master and disciple supplanting that of parent and child, and recasting the republican virtue of universal fraternity. In the Salon de 1846, I noted above, Baudelaire contrasts the “family circle” of an artist’s true disciples with the “artistic apes,” who borrow from any and every master. The most authentic family is brought together by theory and the faculty of taste; the “artistic apes,” by contrast, are a “race,” their artistic failure figured as biological inferiority.

.....