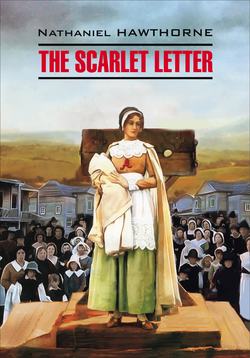

The Scarlet Letter / Алая буква. Книга для чтения на английском языке

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Натаниель Готорн. The Scarlet Letter / Алая буква. Книга для чтения на английском языке

I. The Prison Door

II. The Market-Place

III. The Recognition

IV. The Interview

V. Hester at Her Needle

VI. Pearl

VII. The Governor’s Hall

VIII. The Elf-Child and the Minister

IX. The Leech

X. The Leech and His Patient

XI. The Interior of a Heart

XII. The Minister’s Vigil

XIII. Another View of Hester

XIV. Hester and the Physician

XV. Hester and Pearl

XVI. A Forest Walk

XVII. The Pastor and His Parishioner

XVIII. A Flood of Sunshine

XIX. The Child at the Brookside

XX. The Minister in a Maze

XXI. The New England Holiday

XXII. The Procession

XXIII. The Revelation of the Scarlet Letter

XXIV. Conclusion

Vocabulary

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

Y

Отрывок из книги

A throng of bearded men, in sad-coloured garments and grey steeple-crowned hats, intermixed with women, some wearing hoods, and others bareheaded, was assembled in front of a wooden edifice, the door of which was heavily timbered with oak, and studded with iron spikes.

The founders of a new colony, whatever Utopia of human virtue and happiness they might originally project, have invariably recognised it among their earliest practical necessities to allot a portion of the virgin soil as a cemetery, and another portion as the site of a prison. In accordance with this rule it may safely be assumed that the forefathers of Boston had built the first prison-house somewhere in the Vicinity of Cornhill, almost as seasonably as they marked out the first burial-ground, on Isaac Johnson’s[1] lot, and round about his grave, which subsequently became the nucleus of all the congregated sepulchres in the old churchyard of King’s Chapel[2]. Certain it is that, some fifteen or twenty years after the settlement of the town, the wooden jail was already marked with weather-stains and other indications of age, which gave a yet darker aspect to its beetle-browed and gloomy front. Like all that pertains to crime, it seemed never to have known a youthful era. Before this ugly edifice, and between it and the wheel-track of the street, was a grass-plot, much overgrown with unsightly vegetation, which evidently found something congenial in the soil that had so early borne the black flower of civilised society, a prison. But on one side of the portal, and rooted almost at the threshold, was a wild rose-bush with its delicate gems, which might be imagined to offer their fragrance and fragile beauty to the prisoner as he went in, and to the condemned criminal as he came forth to his doom, in token that the deep heart of Nature could pity and be kind to him.

.....

A lane was forthwith opened through the crowd of spectators. Preceded by the beadle, and attended by an irregular procession of stern-browed men and unkindly visaged women, Hester Prynne set forth towards the place appointed for her punishment. It was no great distance, in those days, from the prison door to the market-place. Measured by the prisoner’s experience, however, it might be reckoned a journey of some length; for haughty as her demeanour was, she perchance underwent an agony from every footstep of those that thronged to see her, as if her heart had been flung into the street for them all to spurn and trample upon. In our nature, however, there is a provision, alike marvellous and merciful, that the sufferer should never know the intensity of what he endures by its present torture, but chiefly by the pang that rankles after it. With almost a serene deportment, therefore, Hester Prynne passed through this portion of her ordeal, and came to a sort of scaffold, at the western extremity of the market-place.

In fact, this scaffold constituted a portion of a penal machine, which was held, in the old time, to be an effectual agent, in the promotion of good citizenship. It was, in short, the platform of the pillory; and above it rose the framework of that instrument of discipline, so fashioned as to confine the human head in its tight grasp, and thus hold it up to the public gaze. There can be no outrage, methinks, more flagrant than to forbid the culprit to hide his face for shame. In Hester Prynne’s instance, however, her sentence bore that she should stand a certain time upon the platform, but without undergoing that gripe about the neck. Knowing well her part, she ascended a flight of wooden steps, and was thus displayed to the surrounding multitude, at about the height of a man’s shoulders above the street.

.....