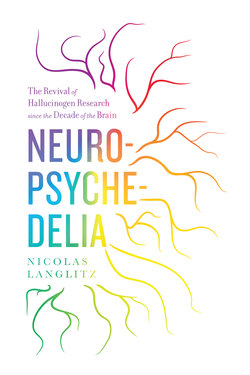

Neuropsychedelia

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Nicolas Langlitz. Neuropsychedelia

Отрывок из книги

The Revival of Hallucinogen Research

since the Decade of the Brain

.....

In this respect, Neuropsychedelia can indeed be read as a contribution to the ethnographic archive documenting human unity and diversity. The French anthropologist Philippe Descola (2005, 2006) has mapped and analyzed the distribution of four ontological predispositions—animism, totemism, analogism, and naturalism—across cultures, or what naturalist anthropologists take to be “cultures.” For the ordering of the world in terms of nature and culture is no more ontologically neutral than an animistic worldview that regards plants as persons to be communicated with through hallucinogenic drugs or, as in totemism, groups particular human beings with particular nonhuman animals instead of other humans belonging to a different ethnic group. Just like the other three ontologies, naturalism, as Descola defines it and as I will continue to use the term throughout this book, is a dualist scheme of metaphysics. It is characterized by the assumption of continuity in the exterior realm (a biological nature shared not just by all humans but by humans and animals alike) and discontinuity in the interior realm (each ethnos is distinguished by its own Volksgeist or culture; animal minds are fundamentally different from the human mind because they lack an immortal soul, consciousness, reason, language, etc.).8 Descola demonstrates that this cosmology has become and continues to be hegemonic among modern Euro-Americans while being ethnologically and historically contingent. For example, Margaret Lock’s (2002) cross-cultural study of the reconceptualization of death as brain death shows how the idea of a living body, in which the person is no longer present, was adopted quite willingly in Europe and North America while meeting fierce resistance in Japan. Descola, however, also argues that, more recently, the bipartite ontology of naturalism thus understood has become unstable and is about to give rise to and will possibly be replaced by a different scheme. This emergent ontology not only promises to leave behind the timeworn modern dichotomies of nature and culture or mind and body but will break with the more fundamental underlying dualism, which, according to Descola, has structured all previous ontologies: a genuine anthropological revolution, it would seem. As an ethnographic case study, this book examines this ongoing transformation of dualist naturalism into monist materialism. It focuses on a mystical variety of the latter, eventually looked at in a perennialist framework that emphasizes recurrence over radical novelty (thereby diverging from Descola’s ontological trajectory and analytic approach).

Since the 1980s, many Anglo-American sociocultural anthropologists (most prominently Asad 1986) have come to question the value of such ethnographic archives in light of doubts about cross-cultural translatability of supposedly universal anthropological categories. Yet this study, although contrasting the United States and Switzerland (and sometimes Germany), does not presuppose or reveal any kind of incommensurable cultural difference. It would be put to good use if readers decided to compare it with other, especially non-Western ethnographic cases—and I will briefly gesture at animistic hallucinogen use in Amazonia when examining an animal experiment with a synthetic ayahuasca concoction in chapter 5.

.....