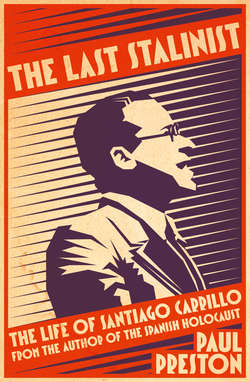

The Last Stalinist: The Life of Santiago Carrillo

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Paul Preston. The Last Stalinist: The Life of Santiago Carrillo

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PREFACE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

1. The Creation of a Revolutionary: 1915–1934

2. The Destruction of the PSOE: 1934–1939

3. A Fully Formed Stalinist: 1939–1950

4. The Elimination of the Old Guard: 1950–1960

5. The Solitary Hero: 1960–1970

6. From Public Enemy No. 1 to National Treasure: 1970–2012

EPILOGUE

ABBREVIATIONS

NOTES

PICTURE SECTION

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

A NOTE ON PRIMARY SOURCES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Отрывок из книги

Title Page

.....

Since the existing electoral law favoured coalitions, Gil Robles eagerly sought allies across the right-wing spectrum, particularly with the Radical Party. The election results brought bitter disappointment to the Socialists, who won only fifty-eight seats. After local deals designed to exploit the electoral law, the CEDA (Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas – or Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Right-Wing Groups) won 115 seats and the Radicals 104. The right had regained control of the apparatus of the state and was determined to use it to dismantle the reforms of the previous two years. The President, Niceto Alcalá Zamora, did not invite Gil Robles to form a government despite the fact that the CEDA had most seats in the Cortes although not an overall majority. Alcalá Zamora feared that the Catholic leader harboured more or less fascist ambitions to establish an authoritarian, corporative state. So Alejandro Lerroux, as leader of the second-largest party, became Prime Minister. Dependent on CEDA votes, the Radicals were to be Gil Robles’s puppets. In return for dismantling social legislation and pursuing harsh anti-labour policies in the interests of the CEDA’s wealthy backers, the Radicals would be permitted to enjoy the spoils of office. Once in government, they set up an office to organize the sale of state favours, monopolies, government procurement orders, licences and so on. The PSOE view was that the Radicals were hardly the appropriate defenders of the basic principles of the Republic against rightist assaults.

Thus the November 1933 elections put power in the hands of a right wing determined to overturn what little reforming legislation had been achieved by the Republican–Socialist coalition. Given that many industrial workers and rural labourers had been driven to desperation by the inadequacy of those reforms, a government set on destroying these reforms could only force them into violence. At the end of 1933, in a country with no welfare safety-net, 12 per cent of Spain’s workforce was unemployed, and in the south the figure was nearer 20 per cent. Now employers and landowners celebrated the victory by cutting wages, sacking workers, evicting tenants and raising rents. Even before a new government had taken office, labour legislation was being blatantly ignored.

.....