Читать книгу Marikana - PETER DUKES ALEXANDER - Страница 1

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление

MARIKANA

Voices from South Africa’s Mining Massacre

Peter Alexander

Luke Sinwell

Thapelo Lekgowa

Botsang Mmope

and Bongani Xezwi

ohio university press

athens

Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701

www.ohioswallow.com

All rights reserved

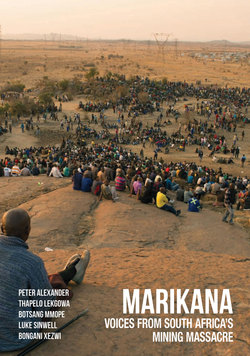

Cover photograph: A view from the mountain. Photograph taken from the top of the mountain on 15 August 2012. The area with trees is the hillock. Nkaneng informal settlement lies beyond, on the right near the top of the photograph. The pylons carry electricity to Lonmin, but none of this goes to the settlement. The area between the hillock and Nkaneng is the killing field, where the first deaths occurred on 16 August.

The following photographs are acknowledged and credited:

Greg Marinovich: front cover and p33; Peter Alexander: pp17 and 41; Reuters/The Bigger Picture: p37, bottom photo, and p149; Amandla magazine: p37, top and middle photos; Thapelo Lekgowa: pp49, 59, 63, 141 and 145; Asanda Benya: p55; Joseph Mathunjwa: p137

First published by Jacana Media (Pty) Ltd in 2012

Revised edition 2013

10 Orange Street, Sunnyside, Auckland Park 2092

South Africa

+2711 628 3200

www.jacana.co.za

© Peter Alexander, Thapelo Lekgowa,

Botsang Mmope, Luke Sinwell and Bongani Xezwi, 2012

© Front cover photograph: Greg Marinovich

© Maps: by John McCann

To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax).

First published in North America in 2013 by Ohio University Press

Printed in the United States of America

Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper ƒ ™

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

hardcover isbn: 978-0-8214-2077-5

paperback isbn: 978-0-8214-2071-3

e-isbn: 978-0-8214-4476-4

Cover design by Maggie Davey and Shawn Paikin

Alexander, Peter, [date] author

Marikana : voices from South Africa’s mining massacre / Peter Alexander, Thapelo Lekgowa, Botsang Mmope, Luke Sinwell, Bongani Xezwi.

pages cm

First published: Auckland Park, South Africa : Jacana Media, 2012.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8214-2071-3 (pb : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8214-4476-4 (electronic) — ISBN 978-0-8214-2077-5 (hc : alk. paper)

1. Strikes and lockouts—Miners—South Africa—Rustenburg. 2. Police shootings—South Africa—Rustenburg. 3. Miners—South Africa—Rustenburg—Interviews. I. Lekgowa, Thapelo, author. II. Mmope, Botsang, author. III. Sinwell, Luke, author. IV. Xezwi, Bongani, author. V. Title.

HV6535.S63A44 2013

968.241068—dc23

2013020687

190

About the authors

Peter Alexander is a professor of sociology at the University of Johannesburg and holds the South African Research Chair in Social Change. In the UK, he gained degrees from London University, was an academic at Oxford University, and held leadership positions in the Southern Africa Solidarity Campaign, Anti-Nazi League, Miners’ Defence League and Socialist Workers Party. He moved permanently to South Africa in 1998. His interests include labour history, specifically Witbank miners, and community protests. He is a co-author of Class in Soweto, published by the University of KwaZulu-Natal Press at the beginning of 2013.

Thapelo Lekgowa is a freelance research fieldworker working with the South African Research Chair in Social Change. After school he worked for a platinum mine. He is a full-time political activist, who learns and teaches on the street. A co-founder of the Che Guevara Film Club and a member of the Qinamsebemzi Collective, he is a member of the Marikana Support Committee.

Botsang Mmope is a herbal healer associated with Green World Africa. Over the past seven years he has worked on various projects with the University of Johannesburg, including research on class, strikes and, recently, the Chair in Social Change’s ‘Rebellion of the Poor’. He is an active member of the Soweto Electricity Crisis Committee.

Luke Sinwell is a Senior Researcher with the Research Chair in Social Change at the University of Johannesburg. He obtained a PhD in Development Studies from the University of the Witwatersrand in 2009. His interests include the politics and conceptualisation of participatory development and governance, direct action and action research. He is co-editor of Contesting Transformation: Popular Resistance in Twenty-First-Century South Africa published by Pluto Press at the end of 2012.

Bongani Xezwi is a freelance research fieldworker who has done work on waste pickers, food production, police brutality and service delivery protests. Recently he conducted life history interviews for the book Mining Faces. He was Gauteng organiser of the Landless People’s Movement and is currently the Gauteng organiser for the Right to Know Campaign.

Acknowledgements

This book includes testimony from strikers who were present at Marikana during the massacre that occurred on 16 August 2012. It offers ‘a view from the mountain’, from the koppie where workers were sitting when police manoeuvres commenced, and where many of our interviews were later conducted. It offers ‘a case to answer’, not the last word, and the judicial commission of inquiry will doubtless yield new evidence about what happened. Nevertheless, given the predominance of official discourse blaming the striking workers for the killings, it is important that their voice is heard.

Funding for our research has come from the Raith Foundation and from the South African Research Chair in Social Change, which is funded by the Department of Science and Technology, administered by the National Research Foundation and hosted by the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Johannesburg. We are grateful to Prof. Rory Ryan, Dean of Humanities, Prof. Lionel Posthumus, the faculty’s Vice Dean for Research, and Lucinda Landen, the Research Chair’s Administration Officer for supporting the project.

Interviews were translated by Bridget Ndibongo, Mbongisi Dyantyi, Andisiwe Nakani and the research fieldworkers. Mamatlwe Sebei helped us by conducting preliminary interviews. We also received assistance from Marcelle Dawson, Shannon Walsh, David Moore and Fox Pooe.

John McCann provided the maps, which add considerably to this book. We are also very grateful to Joseph Mathunjwa, Asanda Benya and Greg Marinovich who kindly provided photographs.

The book was peer reviewed, with the reviewers providing supportive reports and valuable advice. James Nichol, Crispen Chinguno and Rehad Desai also read and commented on parts of the manuscript, as did members of Peter Alexander’s family. Encouraging feedback was received at lectures given in Johannesburg, Detroit, Oxford and London.

Staff at Jacana, especially the editor Maggie Davey, did a superb job, working under considerable time pressures.

Most of all we are grateful to the Marikana strikers and community members we interviewed. They assisted us despite trauma, the watchful eyes of the police, and sometimes hunger. We were also assisted by Joseph Mathunjwa and other leaders of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, and we are indebted to them as well. Many of those we interviewed participated in a reference group, which helped us correct mistakes, and in this revised edition we have addressed further flaws that were drawn to our attention. Remaining errors of fact, interpretation and judgment are our own. We have conveyed the perspective of workers involved in the massacre to the best of our ability, and we hope they will feel that we have done them justice. We have done our best to be accurate and rigorous, but slips are possible in an enterprise of this kind and we apologise in advance for any we have made.

1

Introduction

Encounters in Marikana

Luke Sinwell, Thapelo Lekgowa, Botsang Mmope and Bongani Xezwi

On a blistering hot afternoon in Marikana just a few weeks after the brutal massacre of 16 August 2012, 10,000 striking workers carrying knobkerries and tall whips waited patiently in the sun. Four of us, researchers from the University of Johannesburg, found ourselves in the midst of the crowd. The mood was unclear, but seemed volatile. The workers were singing ‘makuliwe’ [isiXhosa for ‘let there be a fight’]. We felt the force of the movement. One wrong move by the police could shift this peaceful moment into yet another bloody affair.

Workers had started moving in tight-knit battalions, using these formations to protect themselves, especially the strike’s leaders. In what has become an emblemic feature of this workers’ resistance movement, the group stopped and kneeled about 20 metres from the police vehicles. At this point five madoda [men] stepped forward to negotiate. As the workers explained, ‘we can all sing, but we can’t all speak at once’. The five madoda are the voices of the masses behind them, and they could be alternated at any time depending on negotiating capabilities and who they were speaking with. Their plan was to head for the smelter (where the platinum is processed) demanding that it shut down its operations. At this stage, 95 per cent of workers at Lonmin, the third largest platinum mine in the world, were on strike. The smelter was the only unit still operating and the marchers wanted the workers there to join the strike.

Marikana was in effect witnessing an undeclared state of emergency. Police and Lonmin were on one side, and the workers were on the other. Over the next week, a thousand troops were deployed and orders were given by the police that people must stay off the streets. On this particular day, 12 September, the carloads of local and international media that had been camping out at the scene sped off quickly. It seemed like an evacuation. We wondered if we were in the wrong place at the wrong time. Two of us thought it was unsafe and wanted to flee; the other two felt we should stay and observe. In the end we didn’t have much choice. Suddenly the mass of workers kneeled to the ground. There was no space to drive our car away, so we too kneeled down. We learned later from the workers that this was to ensure a calm and quiet environment for the five madodas’ negotiations. The workers were also very cautious. They crouched with their weapons down and to their side, as they did on 16 August when they were attacked. At the same time, they were ready to pick them up and fight, but only if it was necessary to defend themselves.

There was no academic training that could have prepared us for our experiences that day, or for others that came before and after. Each one offered us new challenges as researchers and, more importantly, as human beings. As we learned more about this merciless and bloody massacre through the workers’ voices and eye-witness accounts, we came to the realisation that this was not only preventable, it had been planned in advance. In contrast to the dominant view put forth by the media, government and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), which suggests that the workers were an unruly and dangerous mob who needed to be controlled and contained, we learned that the workers were, and remain, disciplined, peaceful and very well organised. The consciousness of South Africans and others has been scarred by media footage that makes it seem like strikers were charging the police, and defending themselves against savages. As several of the eye-witness accounts of workers who were on the mountain during the massacre testify, and as Peter Alexander recounts, workers were not on the offensive, but were literally running for their lives on 16 August. Some were even shot in the back or in the back of the head while running away.

This is the first book that attempts to understand the massacre on 16 August. It can only provide a starting point for future scholarship and it does not attempt to explain what happened from the perspective of all stakeholders involved. Moreover, when framing the raw interviews that follow, we have extended beyond superficial journalistic accounts, probing into the experiences and lives of the miners. This has only been possible because of a concern to build relationships of trust in a tumultuous, albeit very short, period of time. Too often, researchers go into a locality in order to obtain information from respondents but have limited commitment and never return. This can create a situation in which locals are sceptical of future researchers and refuse to share what they know. We have sustained relationships with many of the workers and have, in small but certain ways, acted in solidarity with them. Of course it would be naïve to assume that this limited engagement over only a few months could produce ethnographic depth, but we hope that it will be the start of a longer engagement.

While the primary focus of our research and interviews was the men who were on the mountain, our most hard-hitting and heart-wrenching experiences were often with the family members, wives and children of the victims. Interviews and other forms of research can take an emotional toll both on the respondent and on the researchers. For Thapelo and Luke, our most painful experience was visiting the families of the deceased in the Eastern Cape, where we began creating biographies of the 34 men who were killed. We attended two funerals and visited seven families in total; entering hut upon hut, seeing family upon family in their rural villages in the poorest province of South Africa, from which most of the workers have migrated. The families were in their mourning period, but still they opened their hearts to us.

We watched six young children playing—none of them had any idea that their father was dead. Rather, as is the tradition, they were told ‘Daddy won’t be coming home anymore’. It is only later in life that they will learn that their father was killed by police for the ‘crime’ of fighting for his right to a better life. To these children things were just normal. We felt helpless when the families asked us for immediate help. People poured out their problems and told us what the solution might be, hoping that we would pass on the message to the powers that be. The words are still haunting us: ‘Go ask government and Lonmin who will be feeding these kids.’

We stayed late one night in Marikana West, the township where many workers live. Bongani and Luke were interviewing one of the workers who had been arrested on 16 August, but he did not want to give us information without the approval of his lawyer. He asked us to walk, through the dark and empty streets, to his home where he had the business card of his lawyer. When we arrived we realised that he was a backyard dweller who was staying in a tiny zinc shack. As we were about to get to his door his wife came out, very distressed, and stated quietly but firmly and in an angry tone: ‘My brothers, get inside! I want to know why are you here?’ As we went inside she demanded proof of our identities. She then explained:

I am asking because there are people around our area who call themselves researchers. Who come to our houses and take our husbands for an interview. And that will be the end of us seeing our husbands. That thing happened in Bop [Western Platinum] Mine when a husband was taken by interviewers and he was never found.

We tried to explain the purpose of our research and why we were in Marikana. We showed them our University of Johannesburg identity cards. After a few minutes she became calmer and accepted our purpose. As we walked out of the shack we became really aware of the tension the community was dealing with. No one felt safe and people believed that outsiders could even kidnap and kill their loved ones. This was the environment of post-massacre Marikana. We decided to avoid speaking to people at night as much as possible, both because we feared for our own safety and because we did not want to make residents feel more uncomfortable.

Late in the afternoon, Botsang entered Nkaneng, an informal settlement in Marikana from which one can see the mountain where the workers were killed. What follows was remembered clearly: I felt uneasy and I shivered. I had never walked in that settlement alone and I did not know how the people there would react to me. It seemed as if everyone was looking at me, and with my yellow University of Johannesburg bag, they could tell that I was a stranger. I was taken by a man into a one-room shack where a woman, a widow of one of the mineworkers killed on 16 August, sat on the bed. One young girl was in the room making tea. That one room was used for sleeping, as a living room, for bathing and for cooking.

The widow and I were left alone and I explained to her the purpose of the research we were doing—so that the next generation could understand what happened during the massacre. She began to open up. I asked her if her husband had ever discussed what happened during the strike. She explained that her husband was earning about R4,000 before he passed away. Her husband’s back, she said, had been full of scars. He was a rock drill operator (RDO), the group that initially led the strike in Lonmin, and the rocks would fall on his back, injuring him. She recounted that on 16 August he was arrested and murdered by the police while he was on strike with others fighting for better pay. The family found him in a mortuary in Rustenburg. It looked as though his skull had been slashed with something like a panga, and the mortuary refused her and the family entry when they wanted to see the rest of the body. She then asked me:

Actually, who ordered the police to kill our husbands, was it Lonmin? Or, was it the government that signed that the police must kill our husbands? Today I am called a widow and my children are called fatherless because of the police. I blame the mine, the police and the government because they are the ones who control this country.

I then proceeded to ask her about the future of her children and she responded:

Our future is no more and I feel very hopeless because I do not know who will educate my children. My husband never made us suffer. He was always providing for us. The government has promised us that they will support us for three months with groceries, but they only gave us three things: 12.5 kg of mealie meal, 12.5 kg of flour and 12.5 kg of samp. That’s it. My husband was sending us money every month and we had enough to eat. Now the mine has killed him. The children of the police who killed him eat bread and eggs every morning while my children eat pap with tea.

Her family consists of six children, five of whom are in school while one is looking for work. The other day, the younger son was asking his older sister: ‘Why is Daddy not coming home?’ He had heard that his father and others were fighting with the police at the foot of the mountain. ‘Where is he?’ he inquired further. A nine-year-old girl asked her [mother], ‘Mommy, why are the police killing Daddy, while we are still so young?’

The above encounters highlight that we did not go to Marikana untouched by people’s experiences with life, death and struggle. The neutral researcher who is detached or not affected by his or her own positionality and perceptions of what is taking place is an illusion. The call to end the strikes and the statement that the workers were threatening the economy or the value of the rand, something we read in the newspapers every day, are providing one story. There is another, that, when compared with their bosses, the workers deserve R12,500, which was their demand, and that they were brutally murdered in the interests of capitalist labour relations of production. While the former ignores the structural and actual living and working conditions of the miners, the latter has received virtually no attention in mainstream analyses.

Perhaps nowhere has the conflict between working-class power and capitalist interests been more acute, and rarely has it spilled more blood. The Marikana Judicial Commission of Inquiry, launched on 1 October 2012 without the knowledge of the families or victims, and with very few workers actually present, may conclude otherwise. It aims to provide ‘truth and justice’ on the basis of evidence presented to the commissioners, but it has not observed working conditions underground and operates in a courtroom environment alienating for ordinary people. In fact, key leaders of the workers’ committee have been arrested, intimidated and tortured during the time in which the commission has taken place, and we therefore question the extent to which the commission is able to provide a space that is not biased against the workers’ perspective. One of the main aims of this book is to fill this gap. On the basis of evidence presented, we maintain that Marikana was not just a human tragedy, but rather a sober undertaking by powerful agents of the state and capital who consciously organised to kill workers who had temporarily stopped going underground in order to extract the world’s most precious metal—platinum.

But not all has been bleak. While we have been saddened, we have also been inspired. The strike at Lonmin symbolised, as much as ever, raw working-class power—unhindered by the tenets of existing collective bargaining and middle-class politics. The workers developed their own class analysis of the situation at Lonmin and, instead of being silenced and falling back when the steel arm of the state mowed down 34 of their colleagues, they became further determined, and more workers united until all of Lonmin came to a standstill.

Workers realised that NUM was too close to the bosses and obstructed their struggle, and that the other union involved, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU), lacked the formal bargaining rights that could advance their demands. In order to be strong, they needed to unite amongst themselves. There had been earlier meetings of representatives from the various shafts, but it was the first general meeting, held on 9 August, that brought together all Lonmin’s RDOs in order to formulate a memorandum that reflected the demands of the entire work population—for a salary of R12,500. An independent workers’ committee was elected representing the three segments of Lonmin—Eastern, Western and Karee—and it became directly accountable to the workers.

The leaders were elected on the basis of their historical leadership in recreational spaces, the community and the workplace. Mambush, or ‘the man in the green blanket’, one of the leaders who was killed during the massacre, had obtained his nickname from a Sundowns’ soccer player named ‘Mambush Mudau’. He was chosen since he had organised soccer games and always resolved minor problems in the workplace. He was particularly well known for having a mild temperament and for his conflict-resolution skills both at the workplace and at his home in the Eastern Cape. Others were chosen because they had previously dealt with emergencies that had occurred in the communities where the miners had originated, including the Eastern Cape, Lesotho, Swaziland, Mozambique and elsewhere. When someone passes away in Wonderkop, workers often show their leadership by taking responsibility for the process of alerting the family of the miner and organising to ensure that the body gets to the respective home and that miners are transported to the funeral. They also manage and collect donations from co-workers to give to the family of the deceased. The workers’ committee was reconstituted several times—some gave up, others were killed, while some remained on the committee from its inception on 9 August until after the strike.

This workers’ agency and leadership is no obscure radical rhetoric or theory of ivory tower academics or non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Rather, it is the unfettered praxis of the working class—which could not be contained, even with national security, the ANC, NUM, and the ideology of the ruling class pitted against it. This book provides a history from below—a story of ordinary people who had previously been relegated to the margins of society. Here, we acknowledge them for their involvement in the strike and for their bravery during an extraordinary and tragic moment in time. The pain of the workers seeps through their stories. It is tangible, sometimes gut-wrenching. We hope you can understand the massacre through the lens of the victims, those who continue to mourn the deaths of their loved ones and colleagues.

In the core of the book, we let the Marikana workers speak for themselves. NUM leaders deny certain of the testimonies given. We undertook more than 30 formal interviews, joined workers’ and community representatives for their meetings, participated in protests, and engaged in countless unrecorded conversations. Finally, we were privileged to be able to meet with a reference group of 14 strikers, many of them part of the leadership, six representatives from the community and two AMCU leaders. We included interviews in this book that are largely representative of the workers’ voices. The interviews that we excluded do not challenge the narrative put forward in the book. Rather, they tend to confirm it.

A large number of the interviews were conducted under the mountain, where workers held meetings in the open air, others were on the streets and some were in people’s homes. Some of the interviews contain material that deals with personal biographies of mineworkers in order to help the reader to understand how and why they came to Marikana. We do not draw this out extensively, but rather allow the readers to form their own impressions.

In the beginning we engaged with almost anybody prepared to talk with us, but later were able to interview leaders of the strike. The people we interviewed stood a very real chance of being victimised by the police or Lonmin, so we have made them anonymous. Anonymity was an undertaking made to our interviewees, and it is one that perhaps contributed to gaining testimony unvarnished by public exposure. For the most part our research was completed before lawyers started taking statements, at which point narratives may have become formalised and less spontaneous. We do not know of previous academic interviews gained so soon after a massacre, and we hope that this contributes to the unique character of the volume.

For the book, space constraints compelled us to make a selection from our main interviews. These are preceded by three background interviews. The first of these is with the president of AMCU, a union that sympathised with the strikers and to which many of them belonged. We think the interview is important because the union’s voice has been under-represented and widely misrepresented in the media, sometimes maliciously so. A second interview is with an RDO, who talks about his job, and a third is with a miner’s wife. We then include sections of three speeches given in the days immediately after the massacre; the first two by strike leaders, the third by the general secretary of AMCU. Ten interviews with mineworkers follow the speeches.

Before the interviews and speeches, there is a narrative account of events leading up to the massacre. The five maps at the start of the book assist the reader in following the story. The reference group enabled us to correct important details, but any mistakes are ours and ours alone, and we apologise, to the workers especially, for any errors. The narrative is the beginning of a history from below, and will be expanded and modified by evidence presented to the inquiry (which will be valuable even if the commission interprets it in ways with which we and the workers disagree). Our main aim in this book has been to indicate what happened, and offer proximate explanations. A deeper history providing a better account of motivations and sociology will require, in particular, attention to life history. In the analysis and conclusion that complete the book we contextualise the massacre to propose a preliminary assessment of its wider significance.

We hope that by the end of the book the reader will have a clearer understanding of what happened in Marikana and why. We hope that you will share with us a sense of the strain and pain of the miners’ lives and labour, the bravery of their struggle, the cruelty tied to their boss’s drive for capacious profits, the corruption of NUM and, most awful of all, the unnecessary police brutality that resulted in the largest state massacre of South African citizens since the Soweto Uprising of 1976.

2

The massacre

A narrative account based on workers’ testimonies

Peter Alexander

On 16 August 2012 the South African police massacred 34 strikers participating in a peaceful gathering on public land outside the small town of Marikana. The workers’ demand was simple. They wanted their employer, Lonmin, to listen to their case for a decent wage. But this threatened a system of labour relations that had boosted profits for Lonmin, and had protected the privileges of the dominant union, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). It was decided to deploy ‘maximum force’ against the workers. Our narrative includes brief accounts of events prior to 16 August, when ten people died, and offers insights into why workers were prepared to die for their cause. It draws mainly on interviews with strikers conducted in the six weeks following the event, and a selection of this testimony appears later in the book.

Some background to the strike

Poverty drove our interviewees to work at Lonmin, and fear of losing their jobs means they tolerate some of the most arduous and dangerous working conditions imaginable. The second background interview in this book provides a glimpse of work undertaken by rock drill operators (RDOs), the category of employees who led the strike. Other underground workers also perform heavy manual work, often doubled up, under the threat of rock falls and machinery accidents. Making matters worse, the air underground is ‘artificial’ and full of dust and chemicals. TB is widespread and illness is common. Of course there are safety regulations, but according to Mineworker 8, who was qualified as a safety officer: ‘We work under a lot of pressure from our bosses because they want production, and then there is also intimidation. They want you to do things that are sub-standard, and if you don’t want to do that and follow the rules... they say they will fire you or beat you, things like that.’1He recalled a worker who had lost his leg because he had been forced, through threat of a ‘charge’, to work in a dangerous place. Peer pressure, too, is a factor. Mineworker 7, a woman, told us: ‘When you start saying “safety, safety, safety”, they say “What should we do? Should we not take out the stof [blasted ore-bearing rock], and just sit here, because you don’t want to be hurt?”’. For the Marikana strikers, the fear of death, present on 16 August, was not a new experience.

In South Africa, a typical working day lasts eight hours, but Lonmin workers we spoke to said they could not ‘knock off’ until they had reached their target, which often meant working 12 hours, sometimes more (Mineworker 8 mentioned working a 15-hour shift). Mineworker 7 complained: ‘They do not even give you time to eat lunch. They just say your lunch box must remain on the surface’. Referring to incessant pressure to reach targets, Mineworker 5 protested that ‘conditions in the mines are those of oppression’. Moreover, it is taken for granted that mine labour also involves anti-social hours, with shifts starting at 05:30 or 21:00 and Saturday-working being a requirement. A group of wives that I spoke with agreed in chorus that their husbands always returned home exhausted. My sense is that today’s Lonmin workers often slave for more hours a week than the 1920s colliery workers I studied, and they probably work harder.2

What does a worker get paid for such hazardous and strenuous work? With few exceptions, those we spoke to said they received between R4,000 and R5,000 per month. These were ‘take home’ figures, and included, so we were told, a standard housing, or ‘living out’, allowance.3Figures vary and calculations are affected by exchange rates, but miners in Australia and the UK can expect to earn about ten times this amount. Workers complained that bonuses and overtime payments were negligible. General assistants claimed they received under R4,000 and a supervisor said he received a little more than R5,000. Such money goes quickly. Many of the workers were oscillating migrants with one family in the rural area and another in Marikana. Inevitably this entailed added costs, especially if the ‘wives’ were unemployed, which was common.4Major expenditure includes rent for a shack (about R450), food (with prices rising rapidly), school and medical expenses, and interest on loans.5Inequality accompanying low pay provides added anguish. For instance, Mineworker 4 observed: ‘You will hear that stocks are up, but we get nothing’. Highlighting the continuing salience of ‘race’, he added: ‘The white people reprimand us if we do not do our work properly or make a mistake. It would have been better to be reprimanded knowing that we were getting pay’.

Several workers had long-standing gripes about their union, NUM, for its failure to support them over critical issues, such as safety and pay. Mineworker 8 claimed that ‘NUM, truly speaking, it always sides with the employer.’ He added: ‘When a person gets hurt here underground, the employer and NUM change the story. They say: “that person got hurt in his shack”.’ Another worker, Mineworker 4, complained: ‘We have been struggling while the union leaders were comfortable, drinking tea. When they have a problem, the management helps them quickly. Even their cellphones are always loaded with airtime, R700, R800’.

Matters came to a head at the end of May 2011, following NUM’s suspension of its popular branch chairperson at Karee, one of Lonmin’s three mines at Marikana. Mineworker 8 provides an account of events. According to him, members ‘loved’ the chairperson, Steve, because he refused to take bribes from management and ‘he always came with straight things... things that NUM never wanted us to know’.6The suspension followed a dispute about a payout from a trust fund established to enable workers to benefit from profits made over the preceding five years. The workers responded to Steve’s suspension by engaging in an unprotected strike. NUM did not support their action, and Lonmin sacked the entire Karee labour force, about 9,000 workers.7Whilst this was a set-back for the workers, nearly all of them were rehired. Because they were ‘re-hired’ rather than ‘re-instated’, workers had to join the union anew. Understandably, few requested membership of NUM, so, significantly (and ironically), the union lost its base at Karee.

According to Mineworker 8, for the next three months ‘the situation was bad’. He then explained: ‘It was very bad because if you do not have a union the employer can do whatever he likes to you’. Nevertheless, workers continued to meet in a semi-clandestine manner, with individuals anonymously convening meetings by pinning a ‘paper’ on a notice board. Even though NUM had been discredited, some workers considered bringing it back, believing that any union would be better than none. However, the majority were opposed to this scenario, and it was at this point that most of the Karee workers went over to the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU). By early 2012, AMCU had gained representation rights at Karee, had won some support at Eastern Mine and had a few people at Western Mine.8AMCU’s presence at Marikana is, then, a recent phenomenon, and, as with the union’s formation back in 2001, the catalyst was NUM’s suspension of a popular leader.9

By July 2012 there was widespread dissatisfaction over pay.10This was particularly acute among RDOs at Karee Mine, who complained that, since they had to work without an assistant (unlike their counterparts at Eastern and Western), they were doing two jobs, and should be remunerated accordingly. The implication was that their pay should be raised from about R4,000 per month, to about R7,500.11Following a mass protest at Karee on 1 August, the manager there awarded his RDOs a bonus of R750 per month.12Elsewhere, RDOs working with an assistant received an extra R500 and assistants got an additional R250. Now, nobody was happy. The Karee men still felt underpaid and RDOs on other mines wanted the same higher increase.13To add to the mix, the Karee RDOs had secured a partial victory without involving NUM, thus boosting their confidence while antagonising the NUM leadership. With RDOs now protesting at different shafts, management took the view that their demands should be presented to central Lonmin structures rather than handled locally.14This provided added stimulus to co-ordinated action, and by 6 August representatives from across the company had established an informal committee. This body then convened a meeting for all Lonmin RDOs.

The strike starts

The assembly took place on Thursday 9 August, Women’s Day, a public holiday, at Wonderkop Stadium (see Map 2). At a rally held two days after the massacre, one of the leaders, Tholakele Dlunga (known as Bhele) narrated as follows: ‘For those of you who do not know, this started on the ninth, when workers of Lonmin gathered to try and address the issue of wage dissatisfaction... to try get our heads together and find a way forward.’15Various demands were being raised, and it was agreed that there should be a common proposal for R12,500 per month.16 However, the objective was to secure a decent increase, and the specific figure was seen as a negotiating position. Mineworker 1 expressed himself thus: ‘Yes, we demanded 12.5 but we... only wanted to talk. We wanted management to negotiate that maybe at the end we will get around 8.9’. NUM was not advancing workers’ claims for better remuneration, and the big problem was getting Lonmin to talk directly with the workers. For Mineworker 1 the thinking was: ‘We will go to the employer on our own and ask for that money... we will go to the employer ourselves because the work we do there is very hard and is killing us.’ The practical conclusion was that workers would deliver their demand to the management the following day.

The meeting brought together workers from across Marikana and it elected a committee that reflected the diversity of the workforce. According to one source, the original committee included two workers from the Western shafts, three from the Eastern shafts and three from those in Karee.17NUM was still the dominant force in Western and Eastern while AMCU prevailed in Karee, but union affiliation was not the issue. Another worker recalled that the committee was ‘representative of all cultural constituencies. It had to be made up of people coming from different provinces’.18Women were not represented, however. According to Mineworker 7, a woman, this was because they were more vulnerable to victimisation by the employer—because there were fewer of them, so more obvious. Responding to the question ‘If they were not afraid they would have been elected?’ she said: ‘They would have been nicely elected’.19Later on, the committee was expanded, and included people who had responsibility for organising the funerals and for welcoming and providing information for visitors.20Significantly, a key responsibility of the original committee was, as Mineworker 3 put it, its ability to maintain ‘peace and order’. He argued: ‘[In] other strikes, people mess up and damage stores and beat people, things like that. So those people [the committee] were able to control people.’ Mineworker 1 added that, in electing the committee, workers ‘wanted to make sure there was order’. In light of subsequent events, this commitment to peace and order, embodied in the leadership of the strike, is highly pertinent. As we will see, the workers were prepared to defend themselves, but they did not initiate violence.

The main decision of the meeting was that the following day, 10 August, the RDOs would strike. At this stage other employees were expected to work normally, though, in reality, without the RDOs, at least according to Mineworker 8, production would be minimal.21The strikers marched to the offices of Lonmin’s local senior management, located at the so-called ‘LPD’ (Lonmin Platinum Division). They were met by a white security officer who said the managers would respond in 15 minutes. But there was no response, and after waiting for three hours the workers’ leaders pressed the matter, only to be informed that their demands had to be channelled through NUM.22Had the management met the protesting RDOs, the deaths that followed could have been averted, but NUM opposed this course of action. Mineworker 10 used the language of paternalism to express his frustration: ‘We blame the employer for not caring about us, because as a parent, as a head office, if there is a dispute in the family he will go and address it, find out what is the problem, so that his children will lay their hearts on the table [and] tell him “this is our problem”’.

Rebuffed, the protesters returned to the stadium. There they agreed that the strike should be expanded to include other workers, starting with the night shift. They also convened a meeting of all workers, to be held at the stadium the following morning.

During the night of 10/11 August, NUM ferried employees into work. The Inquiry heard from Malesela Setelele, Chair of NUM’s branch at the Western Mines, that the local leadership had responded to reports of intimidation and the cancellation of the mine bus service, ‘by using the NUM vehicle, a Toyota Quantum, to transport [employees] to work throughout the mine.’ He explained: ‘this vehicle was not owned by NUM but had been made available to us by Lonmin… for bona fide NUM business’. He added: ‘also, in the early hours of 11 August 2012, [I] used a loudhailer whilst driving around, to inform people that the strike was not endorsed by the NUM and that they should report for duty.’23Setelele regarded his actions as fully justified. From his perspective, he was acting on behalf of his union in response to a strike that was unprotected and unofficial. For him, there was nothing peculiar about risking violent retribution to undertake a task the company itself was unwilling to perform. There were skirmishes that night, and he could be regarded as rather brave. Others, though, will see his role differently, defining him as a ‘scab’. In any case, NUM’s actions surely reduced its credibility among the strikers and intensified existing tensions.

The NUM shootings

That next morning, 11 August, the meeting agreed to follow management’s instruction and put their case to NUM. Some of the workers justified this decision in terms of correct protocol. Mineworker 1, for instance, told us: ‘We decided to go to the NUM offices so that they can tell us what we should do now, because we went to the employer on our own and they [NUM] went and stopped us from talking to the employer, and we wanted them to tell us what to do.’ Mineworker 10 put the matter this way: ‘We acknowledged that we made a mistake, that even though we did not want them [NUM] to represent us, we should have at least informed them that we were going to approach the employer’. Bhele said: ‘We admitted that we took a wrong turn’.24Between 2,000 and 3,000 strikers marched in the direction of the NUM office, located less than a kilometre away in the centre of Wonderkop. It is important to note that they were not armed, not even with traditional weapons. According to Mineworker 10, ‘We were singing, and no one was holding any weapon’. In answer to the question, ‘did you have your weapons then?’, Mineworker 8 responded: ‘No we did not have our weapons on that day.’

After passing the mine hostels, strikers turned left towards the NUM office (see Map 3).25But they never reached their destination. Before them, at a point where the main road ahead was under construction, there was, according to workers, a line of armed men wearing red T-shirts; some carried traditional weapons and some had guns. The strikers halted their march close to the main taxi rank to the right. The armed men open fire. The strikers scattered, mostly in the direction from where they had come. But two men were left behind, badly injured.

At the time there were press reports that these men had been killed, and it is possible that even the police thought this was the case.26Jared Sacks, who researched the event two weeks later, concluded: ‘Once striking RDOs were about 100–150 metres away from the NUM office, eyewitnesses, both participants in the march and informal traders in and around a nearby taxi rank, reported without exception that the “top five” NUM leaders and other shop stewards, between 15 and 20 in all, came out of the office and began shooting at the protesting strikers’.27The implication is that the men in red T-shirts included some of NUM’s local leadership. Apparently security guards were also present, but fired their guns into the air.28

Sacks’ account was corroborated by the testimony we collected. None of the workers who described the scene doubted that the gunfire came from NUM. Mineworker 8 stated: ‘When we were near the offices we found them outside, those people, our leaders, I can put it like that, they came out. Our leaders came out of the offices already having guns, and they just came out shooting’. Mineworker 4’s account is similar: ‘We were not fighting them. They [NUM] were the ones who shot at us... It was the union leaders, the union committee. They were the ones who shot at us.’ Mineworker 9 provided an interpretation: ‘They [NUM comrades] started shooting at us... It became clear that we were not accepted by the very union we voted for, and it also showed that they had strong relationships with our employers’. Similarly, Mineworker 8 concluded: ‘They [NUM leadership] don’t want us getting the money and I am very sure of that... because they are the ones who are always standing with management.’ Mineworker 10 was shocked by NUM’s response: ‘When the NUM saw us approaching its offices it didn’t even ask, it just opened bullets on the workers,’ he said, adding: ‘We thought, as its members, it would welcome us and hear what we had to say, and criticise us, because it had the right to criticise us after we went over its head’.

According to contributors in our Reference Group discussion, one of two workers hit by bullets managed to clamber over the fence that separates the road from the hostels, and was able to escape. The second man got as far as the smaller taxi rank just inside the hostel grounds, where he allegedly died.The inquiry heard testimony from the man who eventually escaped through the fence. He described how he had been shot in the back and then, having collapsed, was badly wounded on his head, by men who, he claimed, said they wanted to finish him off. He was able to identify his assailants, and it is possible that an attempted murder charge will now be brought against them. Evidence was presented that the second man was also shot in the back.29

In his opening address to the Farlam Commission, Karel Tip, acting on behalf of the NUM, accepted that some of the union’s members used firearms. He argued that this was ‘justified’ in the circumstances. It is now agreed that the two strikers who were shot did not die, but it is understandable that many workers thought that this was the case. The two men were, however, seriously injured and hospitalised, and it was, it would seem, a matter of good fortune that they were not killed.30

It is highly likely that many of the strikers who were attacked were members of NUM. This claim is based partly on a deduction. On 10 August Lonmin took out an injunction against the striking RDOs, naming 3,650 individuals. Of these, 13% had no union affiliation, 35% belonged to AMCU and 52% were members of NUM (which reflected the fact that AMCU was only dominant at Karee). Possibly a disproportionately high number of NUM RDOs refused to join the march (NUM claimed that some of its members only joined the stoppage because of intimidation), and perhaps some marchers were not RDOs, so we cannot assume that Lonmin’s percentages reflected the numbers outside the NUM offices. However, from our Reference Group and from the individual testimonies we recorded it is clear that a high proportion of the marchers were NUM members. Moreover, when it came to the massacre on 16 August, 10 of the 34 men who died were members of NUM, demonstrating continuing support from NUM members throughout the conflict.

In any case, the event was a turning point. Workers fled from the scene and headed towards the stadium. But security guards refused them re-entry, threatening to use force if necessary. The workers then headed for Wonderkop Koppie, the so-called ‘mountain’, two kilometres further west. This would be their home for the next five nights and days, though, of course, they did not know this at the time. One advantage of staying on the mountain is that it provided a good view. According to Mineworker 9, ‘The mountain is high [and] we chose it deliberately after NUM killed our members, so that we could easily see people when they come’. Though some workers went home at night, he and Mineworker 8 both refused to do so, because they had a fear of being killed (probably by NUM). Mineworker 8 described life on the mountain: ‘We were singing, talking and sharing ideas, and encouraging each other, that here is not the same as your house, and one has to be strong... You are just sitting here, and making fire and putting money together’. Mineworker 9 added: ‘We were helped by the people in the nearby shacks who brought us food’.

It was only at this point, after the shooting of their comrades, that workers gathered their traditional weapons. Mineworker 8 responded to the question ‘So it was NUM that pushed you into carrying weapons?’ with: ‘Yes, because they shot at us and we were afraid that they will come back. We do not have guns, and so we thought it will be better that we have our traditional weapons.’ Mineworker 1 provided valuable insight on the issue. ‘My brother’, he began, ‘what I can say about the... spears and sticks [is] that we came with [them] from back home. It is our culture as black men, as Xhosa men... Even here... when I go look at anything... at night [such as the cows]... I always have my spear or stick... or when I have to go urinate, because I don’t urinate in the house... I take my stick’. Then he added: ‘A white man carries his gun when he leaves his house, that is how he was taught, and so sticks and spears that is the black man’s culture’.

Deaths

The next morning, workers again went to remonstrate with NUM officials. Again they numbered between 2,000 and 3,000, but this time some were carrying their weapons. Beyond the stadium, inside the hostel area, they were stopped by mine security (who included two ‘boers’) and ‘government police’ who had a Hippo with them.31According to Mineworker 4: ‘The mine security guards shot at us. But we did not go back. We kept going forward.’ From subsequent conversations with workers we learned that two security men were dragged from their cars and killed with pangas or spears. Their cars were later set ablaze, and we saw the remains of one of these, which was located on a corner by the small taxi rank inside the hostel area. These new killings occurred close to where the striker had allegedly died the day before (see Map 3).

Later the same day, 12 August, two NUM members were stabbed to death. These were Thapelo Madebe and Isaiah Twala. The following day, a third NUM member, Thembalakhe Mati, was killed, this time by gunshot.32The circumstances surrounding these killings are obscure, and there is no evidence that they were ordered by strike leaders or AMCU officials. However, they contributed to a sense of outrage, especially within the NUM leadership.

Monday, 13 August, was another day of bloodshed. Early in the morning, strikers received information that work was being undertaken at Karee No. 3 shaft (known as K3). Since this was the first full day of the strike it was not surprising that there was an element of scabbing, and a relatively small contingent was despatched to explain to the workers that they were expected to join the action. Accounts of the size of this ‘flying picket’ (to use a term from the UK) vary from under 30 to about a 100. See Map 2 (this shows that the entire journey would have been about 15 kilometres there and back). Mineworker 2 provides a detailed account that is corroborated in other interviews and by versions we received from workers in loco. At K3 the deputation spoke with security guards, who said that, while they would look into the matter, as far as they knew nobody was working. According to the workers, the guards told them that rather than returning to the mountain via the K3 hostel and Marikana, which would have been the easier route, they should take paths across the veld (mostly flattish rough ground with occasional thorn trees and other shrubs). For the hike back to the mountain the group may have grown a little, but all our informants placed its size at under 200 people.

At first the route follows a dirt track alongside a railway line. After a detour around a small wetland, the workers found their way blocked by a well-armed detachment of police that had crossed the railway line on a small dirt road and turned left onto the track (see Map 4). The precise size of the police contingent is unclear, with Mineworker 2 saying the police included ‘maybe three Hippos and plus/minus 20 vans’ and a Reference Group contributor specifying about 14 Hippos but not mentioning vans (possibly treating armoured police ‘vans’ as ‘Hippos’). The police forced the workers off the path and encircled them (with a line of police stretched out along the railway line). The response, it seems, came from Mambush, later famous as ‘the man in the green blanket’ and probably the most respected of the workers’ leaders. He is reported to have said that, while they were not refusing to give up their weapons, they would only do so once they reached the safety of the mountain. Mineworker 2 recounts that a Zulu-speaking policeman then warned that he would count to ten, and if they had not conceded by then he would give the order to fire. After the counting had started the workers began singing and moved off together towards the weakest point in the police line, which was probably to the north-east, the direction of the mountain. At first the police gave way but, according to Mineworker 2, after about ten metres they started shooting. In the commotion that followed, three strikers and two police officers were killed. One of the strikers and two of the police were killed to the west of the dirt road that crosses the railway line (see Map 4). There is a suggestion that one of the police may have been shot, accidentally, by another police officer.33On the other side of the road, a wounded civilian was hidden inside, or next to, a shack, but this was noticed by the police, who pursued him and then shot him several times at close range. The fifth fatality occurred north of the shack and to the east of the river (see Map 4). This worker was clearly fleeing.

Photographs of the two deceased police officers were widely and rapidly circulated within the police service, mainly through cellphones (mobiles). These showed the grisly remains of men who had been hacked to death, thus, one assumes, re-enforcing a desire for retribution. It would be surprising if the railway line event, and the way it was handled by the police, were not a factor in the subsequent massacre.

Failed negotiations

On Tuesday, 14 August, a police negotiator arrived at the mountain, accompanied by numerous Hippos. He was a white man, but addressed the workers in Fanakalo, which was regarded as novel for a white policeman.34He said that he came in peace, in friendship, and just wanted ‘to build a relationship’ (a formulation used in a number of interviews). He entreated the workers to send five representatives, five ‘madodas’ to talk to him (Mineworker 3). ‘Madodas’ literally means ‘men’, but it sometimes carries the connotation of self-selected or traditional leadership, thus implying a certain ‘backwardness’, in contrast to trade unions. In reality, as we have seen, the workers operated through an elected and representative workers’ committee, one typical of well-organised modern strikes. As requested, the strikers selected five representatives, and sent them to talk to the negotiator. Mineworker 3 provides a detailed account of proceedings. The representatives claimed that the negotiator and his team refused to leave the Hippo and speak to them on the same level, face to face. They also refused to provide their names, which was disconcerting to the workers, and at some point, later on, an amadoda tried to take a photograph of the police on a cellphone, but this was stopped. A worker who was part of the delegation claimed that one of the senior police was a white woman and that a company representative was also sitting in the Hippo. Apparently this was denied by the police.35Nevertheless, the five madodas conveyed the view that all they wanted was to talk with their employer. They wanted him to come to the mountain, but, if necessary, they would go to him. The police departed, leaving workers with the impression that they would inform the employer of their request. However, when they returned the next day, Wednesday, 15 August, it was without a representative of the employer.36Lonmin was refusing to talk to its striking workers. According to a strike leader, only three of the five madoda would survive the massacre that was imminent.37Later on Wednesday, towards sunset, Senzeni Zokwana, president of NUM, arrived in a Hippo. Mineworker 10 complained that: ‘We didn’t see him, we were just informed to listen to our leader.’ Mineworker 1 concurred: ‘He was not in a right place to talk to us as a leader, as our president, this thing of him talking to us while he is in a Hippo. We wanted him to talk to us straight if he wanted to.’ When he did speak, his message was simple, crude even. ‘Mr Zokwana said the only thing he came to tell us was that he wanted us to go back to work, and that there was nothing else he was going to talk to us about’.38Apparently the workers repeated their demand that they only wanted their employer to address them, not Zokwana.39About five minutes after Zokwana left, Joseph Mathunjwa, president of AMCU, arrived, and although he was accompanied by a Hippo, he came in his own car.40According to Mineworker 6, Mathunjwa said that he was sympathetic to the strikers, but cautioned them that he too had been denied access to the employers. However, he added that because he had members at Karee he would try again to meet them the following day.

The police presence had increased on the Wednesday, and on the Thursday morning, 16 August, more forces arrived. This time the police were accompanied by ‘soldiers’, probably para-military police dressed in similar uniform to soldiers.41Trailers carrying razor wire (which the workers mostly refer to as barbed wire) also arrived.42Mineworker 9 says that workers ‘shouted’ for other workers to join them. In the early afternoon on this fateful day, Mathunjwa returned, this time without any escort.43According to Mineworker 10, he told his audience that the employer never ‘pitched’ for their scheduled meeting, using the excuse that he was at another gathering (presumably with police chiefs).44Mineworker 10 added that Mathunjwa told the strikers they should return to work, because if they stayed on the mountain any longer a lot of people might die. There was some scepticism about this advice. For instance, Mineworker 2’s response was that Mathunjwa should ‘go back, because we are not AMCU members, we are NUM members’. Mineworker 8’s response was that, on the mountain, they had been eating together and making fire together, and it was like home. They weren’t leaving, he said, adding that ‘we do not want any union here’. Mineworker 9’s account was slightly different again. According to him: ‘We said, Comrade, go home. You did your best, but we will not leave here until we get the R12,500 we are requesting, and if we die fighting, so be it.’ The last phrase resonated with a famous speech by Nelson Mandela, and Mineworker 9 pursued this, albeit with a twist. He said: ‘We should talk and negotiate through striking, that is how Mandela fought for his country.’ Mathunjwa made one last attempt to convince the workers. He went down on his knees and begged them to leave.45Few accepted his plea. Twenty minutes later the massacre began.

The massacre of 16 August 2012

There are photographs of the assembled workers when Mathunjwa was addressing them, just before he left the scene (see inside back cover for example). They are a large crowd, roughly 3,000 strong, spread between the mountain, the hillock to its north and lower ground between the two (see Map 5). They look peaceful, not threatening anyone. Yet, additional armed police were rapidly brought to the field around the mountain, and some were manoeuvred into new positions, almost encircling the workers. Much of this build-up was watched by strikers still sitting on the mountain. The media quickly retreated from just below the mountain to a safer position, from where they would record the opening of the massacre.46Mineworker 8 reveals Lonmin’s direct involvement. Two ‘big joined buses from the mine’ arrived delivering yet more police to the scene. Also ‘soldiers’ appeared on top of their Hippos. We later learned there were vehicles from each of the neighbouring provinces, but it seems there was even one, perhaps more, from the Eastern Cape. Mineworker 4 tells of strikers talking to homeboys from towns in the Transkei, and a witness quoted by Greg Marinovich mentioned that he’d been told that an Eastern Cape policeman had claimed ‘there was a paper signed allowing them to shoot’.47Mineworker 8 says: ‘What really amazed me was that the truck that carries water and the other one that carries tear gas, they were nowhere near, they were standing right at the back’. Ominously, mine ambulances were already present when the shooting started.48

A major concern for the strikers was seeing the police rapidly reel out the razor wire using two or more Hippos. See Map 5. This shows the approximate position of the wire, which was positioned in a line northwards from a pylon close to the electrical power facility and then took a turn to the right in the direction of a small kraal (the first of three in that area). Mineworker 2 said they were being ‘closed in with a wire like we were cows’, and one of the miners’ wives said that the fencing was for ‘rats and dogs’.49The comments are significant because the police had begun treating the workers as if they were no longer human beings. A group of the miners’ leaders, including Mambush, tried to remonstrate with the police near a point marked + on Map 5. Their plea that a gap be left open, so that strikers could leave like human beings, fell on deaf ears. With guns aimed at the workers, it was clear that the police were now ready to shoot. A large number of the strikers rushed north-eastwards in the direction of Nkaneng, where many of them lived.

It was about now that the first shot was fired. According to members of our Reference Group, this came from behind the miners who were heading towards Nkaneng, hitting a worker at a point close to the second + on Map 5. Some fleeing strikers, including several leaders, now turned to the right, hoping to escape through a small gap between the wire and the first kraal. Most continued onwards, so there were no hoards of armed warriors following this leading group, as suggested in some media coverage though not by TV footage. One woman, a witness, later made the point that the strikers were running with their weapons down, and so were not a threat, and this can be seen in some photographs.50 It was too late. The leaders’ path was blocked by Hippos, and they were trapped. Mineworker 2 recalled: ‘People were not killed because they were fighting... We were shot while running. [We] went through the hole, and that is why we were shot.’

The order was given to fire. The command may have come from a white man, who did so, according to Mineworker 6, using the word ‘Red’.51There were no warning shots.52According to Mineworker 2, who was clearly present, ‘the first person who started to shoot was a soldier in a Hippo, and he never fired a warning shot, he just shot straight at us’. Within seconds seven workers had been slain, killed by automatic gunfire right in front of TV cameras (see Map 5). In photographs, their bodies are pictured in a pile, with a shack nearby. Moments later, another group of five men were killed, their bodies crushed against a kraal, as if cornered without any possibility of escape. Mineworker 8 questioned: ‘I get very amazed when the police say they were defending themselves, what were they defending themselves from?’

Some of the leading group were able to turn back. They joined other workers scattering in all directions. Many fled north; some went westwards in the hope of reaching Marikana; others just ran as far as they could and as quickly as their legs would carry them; and one, at least, crawled a long distance across rough ground, hoping to dodge bullets and Hippos.53It is difficult to imagine how terrifying and disorienting the situation must have been. There were armoured vehicles all around; there were helicopters in the sky; horses charging to and fro; police sweeping through on foot; stun grenades making a noise as loud as a bomb; tear gas; water cannons; rubber bullets; live rounds; and people being injected with syringes. This was not public order policing, this was warfare. A strike leader remarked: ‘Water, which is often used to warn people, was used later on, after a lot of people were shot at already’.54Perhaps confirming this, on 20 August we found blue-green water-canon dye in an arc well to the west of the mountain, far from the initial front line. Similarly, Mineworker 10 asserted: ‘They lied about rubber bullets. They did not use them.’ I have not heard of the use of injections before, and it remains to be seen why they were used and to what effect. There were many complaints that workers were trampled to death by Hippos.55Some had been made dizzy by tear gas and some had stumbled perhaps.56Some people we spoke to described deceased workers whose bodies were so badly crushed they could only be identified by finger prints. Helicopters used a range of weapons.

Of the 34 workers who were slaughtered on 16 August, 20 died in the opening encounter or very soon after and close by. The remainder were killed in one small location. This is the place known by some as Kleinkopje. But South Africa is littered with small koppies and it seems more appropriate to call it Killing Koppie. Here, some 300 metres to the west of the mountain, on a low rocky outcrop covered with shrubs and trees, the police killed 14 workers. On a grassy plane with few large bushes this was an obvious place to hide from bullets and Hippos, but it was relatively easy for the police to encircle and then move in for the kill. Workers told us that two helicopters came from the north, depositing their paramilitary cargo, and two or three Hippos moved in from the south. Mineworker 9 recalled: ‘That is where some of our members went in and never came back... the people who ran into the bush were ones being transported [in ambulances and police trucks]’. On 20 August, when we were directed to the Killing Koppie, we not only found letters on the rocks that had been spray-painted in yellow, marking sites from where bodies had been removed, we also saw pools and rivulets of dried blood discoloured by the blue-green dye. Mineworker 5 was present on the Koppie; one of those lucky to survive. He recalls: ‘You were shot if you put up your hands.’ Needless to say, he did not raise his hands. Rather, he says: ‘I was taken by a gentleman who was of Indian ancestry. He held me and when I tried to stand up I was hit with guns, and he stopped them.’ A drop of humanity in a sea of bestiality. Allegedly, some workers were disarmed and then speared by the police (we heard this from a number of strikers including Mineworker 5). Whatever view one takes of the initial killings, it is clear that the men who died on the Killing Koppie were fleeing from the battlefield. Moreover, the precise locations of deaths and the autopsy evidence tend to reinforce the account provided by Mineworker 5, leading one to the conclusion that Killing Koppie was the site of cold-blooded murder.57

Immediate aftermath

Those who were arrested had to suffer ill-treatment and torture. Soon after his arrest, Mineworker 5 was told by police, spitefully it seems to me: ‘Right here we have made many widows... we have killed all these men.’ As with most of the other arrested survivors, he was initially held at a Lonmin facility known as B3. He pondered: ‘It seemed as though the police did not belong to the government, but that they belonged to the company.’ Later he was taken to a police station, where he had to sleep on a cement floor without a blanket (in the middle of winter), received only bread and tea without sugar, was unable to take his TB medication, and was refused a call to his children even though he was a widower. Other detainees were tortured. Early in the struggle, Mineworker 8 thought the police would protect the workers from NUM. After the massacre he was venomous: ‘I will just look at them and they are like dogs to me now... when I see a police now I feel like throwing up... I do not trust them anymore, they are like enemies.’

The massacre was an intensely traumatic experience for all its victims. Mineworker 1 recalled: ‘We had pain on the 16th, but it was more painful... on the 17th... because [if] one [comrade] did not come back... we did not know if he had died or what’. Mineworker 8 drew on his knowledge of history, but this did not hide his suffering. ‘Hey my man,’ he started, ‘my head was not working on that day and I was very, very numb and very, very nervous, because I was scared. I never knew of such things. I only knew of them like what had happened in 1976 and what happened in 1992, because of history.’ Linking this back to the present, he continued: ‘I would hear about massacres you see. I usually heard of that from history, but on that day it came back, so that I can see it. Even now, when I think back, I feel terrible, and when I reverse my thinking to that, I feel sad, still.’58For Mineworker 10, trauma was linked with a political assessment. He started: ‘I am still traumatised by the incident. Even when I see it on TV, I still get scared because I could not sleep the days following the incident.’ He then concluded: ‘It is worse because this has been done to us by a government we thought, with Zuma in power, things would change. But we are still oppressed and abused.’

The bloodshed, cruelty and sorrow of the massacre could have led to the collapse of the strike. That is what Lonmin, the police and NUM had expected. But it was not to be. Somehow, surviving leaders managed to rally the workers and stiffen their resolve to win the fight. This must have taken great courage and determination. Eventually, the company did agree to talk to the workers. Having done so, it conceded large increases in pay (22 per cent for RDOs) plus a R2,000 return-to-work bonus.59When this was announced on 18 September, it was greeted by the workers as a victory, as indeed it was. The scale of this achievement was soon reflected in a massive wave of unprotected strikes, led by rank-and-file committees, which spread from platinum mining, into gold, and on to other minerals, with ripples extending further into other South African industries. 34 workers were murdered by the police on the battlefield at Marikana, but they did not die in vain.

3

Background interviews

Undertaken by Thapelo Lekgowa and Peter Alexander

Joseph Mathunjwa, President, Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union

Joseph Muthunjwa: I was born in 1965. I am from the family of priesthood under the Salvation Army. The relatives of my mother were located around Johannesburg, Witbank, Ermelo. Some were mineworkers. After my high school I came to Witbank looking for a job. I couldn’t go to further education, my father was not getting paid enough to assist. I started working in construction around Witbank, close to the mines. Then I went to Tweefontein Colliery. I was not long there. Then I went to Douglas Colliery. I was working in a laboratory and later in the materials department, but these were not regarded as white-collar jobs, because within the very same departments those jobs were also classified for coloureds, Indians and whites. We were under categories 3 to 8 in those days, but they were on higher categories.

Interviewer: Do you remember the 1987 strike? As I recall one of the issues in Witbank was about workers wanting to make the hostels family hostels.

JM: I remember that one. It lasted for a month. I think it was a combination of many things, not really hostels per se. It was called by NUM.

Interviewer: From then, through to when AMCU was formed, it was 13 years or something like that, do you have strong memories of work in that period?

JM: I think from ’86 my presence at work was felt because I didn’t wait to join a union to express how I see things. Firstly, when I realised that we were confined in the hostel, [with] no transport for black workers to take them to the locations [townships], to stay with their families, I was the first black person who jumped into a white [only] bus in 1986, forcing my way to the location. Subsequent to that I was the first black person to enter into a white recreation club within the mine. That led me to many troubles with mine management. I was the first person at Douglas who led a campaign [for] workers to have houses outside the mine premises. So I led many campaigns. That was ’86, ’86. NUM was there, but it was not really, what can I say, more instrumental about living outside the mine. It was more focused on disciplinary hearing[s], but not this global approach on social issues.

Interviewer: How did you organise?

JM: I would go to the meetings, and people would hear about myself. Then I would go to the general managers’ office. All things started when I boarded the white transport by force. Then the managers had very much interest. ‘Who is this guy?’ They said: ‘There’s the union’. I said, the union does not address these issues. Then they asked: ‘What other issues?’ Then I made a list of those issues, and I started a campaign for those issues.

Interviewer: Are there things you remember during the 1990s?

JM: I still remember, there was a Comrade Mbotho, from Pondoland, who passed on, from Pondoland. He was very strong. He was like a chairman of NUM at Van Dyk’s Drift. He was a very strong Mpondo man. I remember he organised a big boycott of using those horse-trailer buses, for transporting you from hostel to shaft. How can I explain this? You have the head of the truck which has a link and it pulls like a bus, but semi bus. You cannot see where you are going, you are just inside, like you are transporting horses, race horses. He [the manager] changed the buses to give proper buses to the workers.

Interviewer: Later on you were expelled from NUM, so at some stage you must have joined?

JM: Yes. The workers were aware that there is this young man working in the mine and they said: ‘You have to be part of NUM in order [to fight for] all the issues that are affecting workers.’ Then I joined NUM, and the management didn’t like the manner in which things were raised, and I was transferred... When they saw that I was attending most of the meetings [and] becoming more influential to the workers, they sent me to one of the stores. It’s called Redundant Store, where all items that are no longer in use will be parked there. It was like a Robben Island of some sort. You cannot be among the workers; you cannot attend meetings. To attend meetings I had to travel more than 20 kilometres, [and] when you get there the meeting is finished. But nevertheless being part of the NUM, I was elected as a shaft steward. Then I represented workers. I still remember when there was a fatal underground [accident], and the worker died in a very mysterious way, then we were called in. That was my first experience. They [the attorney for the company] wanted us to sign some documents, a prepared document. I said: ‘Why should we sign this document?’ They said: ‘No, it’s about the person [who] passed on [so that] we all cover ourselves.’ I said: ‘Why should we cover ourselves as shaft stewards, when we are not working in that area?’ So I defied. Most of the shaft stewards signed those documents.

Interviewer: Were you a shaft steward just for your department, or on the mine itself? How were you organised as an NUM branch?

JM: For the department, on the surface. You’ve got your branch executive and your shaft steward council. One branch covers one colliery.

Interviewer: And then workers would take their grievance to this shaft steward?

JM: Yes, to the shaft steward. And then shaft steward to the council, because we do have our ‘during-the-week meetings’, [collecting] all the grievances from different department[s]. Then we go to the mass meeting. We tell them what’s happening; then we formulate an agenda to meet with management.

Interviewer: And these days is there complete separation between AMCU and NUM on each of the mines, or are there places where they come together, as shaft stewards perhaps?

JM: We are completely separate. NUM will have their shaft steward council and AMCU will have its own. And the only [place] where we meet together, it’s where we are dealing with issues like health and safety, employment equity and all those forums, because those are the legislated forums, which don’t define a union. But where we are the majority, so AMCU will run the show; in as much [as] NUM is the majority, then they will run the show.

Interviewer: Let’s go back to your NUM days.