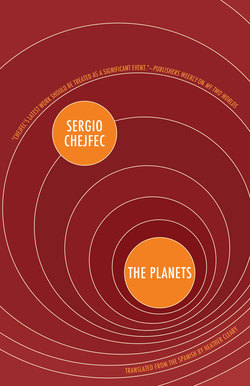

The Planets

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Sergio Chejfec. The Planets

Отрывок из книги

Praise for

Sergio Chejfec

.....

Yet it is also true that it was a mistake not to face her. A mistake and, if it does not sound inappropriately elegant, a gaffe. It was to turn my back on M, who had brought about the encounter (I don’t mean this only in a figurative sense). Mute, with his mother already behind me and probably on her way home, I immediately regretted what I had done—or, rather, what I had not done. So I ran, wanting to make it all the way around the block—Padilla, Gurruchaga, Camargo—and force a new encounter, which this time would be unequivocal. Despite the fact that it was planned, and something of a ruse, it was more real and natural this way. Distracted, I turned the last corner and saw her walking toward me, as I had moments earlier, watching me. Now she, too, was ready to acknowledge me. Sometimes we need to shield ourselves from spontaneity in order to endow our actions with a measure of truth. Never before that afternoon had I seen a face that showed so much, forgetting modesty, fear, and precaution. A face with nothing to hide and nothing to offer: that was the face of M’s mother. Her eyes, fixed on mine, clouded over intermittently, giving her smile an air of melancholy. (We were standing face to face, waiting for who knows what.) All of a sudden, I realized that she was possessed by a deep conviction: that of having lost M forever. This idea, which at the time I myself did not dare to consider, surprised me. I admired this awareness, the certainty of it, because—though morbid—it followed the logic of a profound sense of peace. Yet, strangely, I was unmoved (I felt neither agitation nor grief). She was convinced of the fate of her son: this could be discerned in the veil of uncertainty, of vacillation, that shields people after a loss. Waves of stupefaction swelled from the cobblestones in the street and the trees along the sidewalk. M’s mother seemed to be at once a child, an old lady, and unquestionably a grown woman. At last the tears came—this, too, was inevitable—and before saying goodbye she asked me and, through me, the others, to stop by and see them now and then. Again I found myself at a loss for words. I thought that she—to whom I could say nothing, knowing nothing, particularly about what was going on inside her—demonstrated a remarkable, substantial wisdom by asking that we visit her “now and then,” mainly because she broke the silence from which I had been unable to free myself. As I clung to her shoulders, I understood that it was of secondary importance whether this wisdom was born from her experience, her intuition, or some other thing; what mattered was that it was wise. Some time passed this way, the street also in silence. Then we each continued on our way; some things, at least, had returned to normal. After a few steps it occurred to me to watch M’s mother as she walked away. I imagined that her back could tell me something, who knows, that it might have something to add or a different way of communicating. But I stopped myself before turning; I had the feeling that I was about to ruin something, and that this something was not secondary, but rather meant a great deal. I was only a few meters from her, still within the danger zone that exists between people: R might be able to feel the weight of my gaze from behind her, and doubtless would have considered it crass that I would stop to look at her. She had inspired me to run around the block, that much was clear, and it was she who had rescued me from silence as we embraced. If it had not been for M’s mother, I thought as I walked away, we would have remained joined, fossilized there on the sidewalk like one of those statues that commemorate a foundational moment.

Their first conversation took place one afternoon a few days after they met, when the other asked him about the soccer field a few blocks from his house. “What field?” responded M; he was either distracted or had forgotten. The other had to clarify: “Club Atlanta’s stadium, it’s famous.” He wanted to know whether, given how close it was to his house, he could hear the goals, the chanting of the fans, or even the announcer. M said, with affected confidence, that he could; too emphatically to conceal a swell of pride. The other vacillated, saying that he had thought it would depend on the direction of the wind. Even if he lived nearby, he might not be close enough to hear everything. M conceded that of course he couldn’t hear everything, that wasn’t what the other had asked, but he did live close enough to the field to hear the goals and the chanting, regardless of the wind. When it blew toward his house he heard better and when it blew the other way, not as well, but he could always hear it. In any case, he continued, you couldn’t say that he didn’t live close enough: “My house is five blocks from the stadium if you follow the streets, but only two hundred meters if you follow the tracks,” he explained. The train was the clearest indication of proximity, perhaps even of contiguity, but at the same time, on match days the train’s whistle made it hard to hear the sounds of the stadium and so, he acknowledged, sometimes the distance wasn’t ideal. The other listened silently. The truth is, continued M as he walked, that even if they are playing an important game on a Sunday, it can be hard to hear anything if it’s really windy. Of course, this has nothing to do with the distance; everyone knows that it is impossible to hear in strong wind unless you are very close, even right alongside.

.....