Читать книгу A Girls' Guide to the Islands - Suzanne Kamata - Страница 1

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSuzanne Kamata

A Girls’ Guide

to the Islands

Suzanne Kamata is the author of the award-winning young adult novel Gadget Girl: The Art of Being Invisible, and the author or editor of a range of books. Originally from Michigan, she now lives in Tokushima, Japan, with her family, and teaches EFL at Tokushima University. Suzanne holds an MFA from the University of British Columbia.

First published by Gemma Open Door for Literacy in 2017.

Gemma Open Door for Literacy, Inc.

230 Commercial Street

Boston MA 02109 USA

www.gemmamedia.com

© 2017 by Suzanne Kamata

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

Printed in the United States of America

978-1-936846-57-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for

Cover by Laura Shaw Design

Map on page 98 by Buyodo.

Gemma’s Open Doors provide fresh stories, new ideas, and essential resources for young people and adults as they embrace the power of reading and the written word.

Brian Bouldrey

Series Editor

Open Door

To Lilia, travel companion extraordinaire.

1

How can I get out of the promise that I made to my twelve-year-old daughter, Lilia?

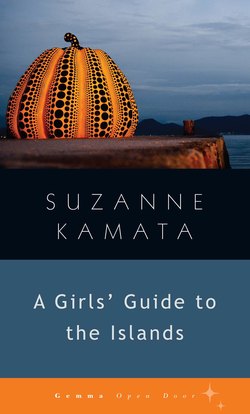

A few weeks ago, I invited her to go with me to Osaka. We would take in an art exhibition. The latest works of the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama would be on display at the National Museum of Art. The show finishes at the end of March.

Kusama is famous for her polka-dotted pumpkin sculptures. I’ve been interested in this artist for a while. This seemed like the perfect opportunity to get to know her work better. At first, I’d been planning on going alone. Maybe I could go while my twins were at school. It occurred to me, however, that Lilia was old enough to appreciate Kusama’s art. Plus, if we went together, I wouldn’t have to worry about hurrying back to pick her up from school. My son would be okay left alone for a few hours. My daughter is multiply disabled. She often needs help.

Of course, when I proposed this outing, Lilia was eager to go. Art! A bus trip to Osaka! Polka dots! What’s not to like?! So we made plans. Now Lilia is entering spring break and the exhibit is drawing to a close. I am dreading the trip. I doubt that my daughter can keep herself entertained on the long bus ride to and from Osaka. If I go by myself, I can read, daydream, and doze. With Lilia along, I might have to chat in sign language for hours. It wouldn’t be relaxing.

Also, it would be tiring. Usually, going to a big city involves a lot of walking. We’d be wandering around the museum. I’d probably have to push Lilia’s wheelchair up inclines. I might even have to carry her. At the thought of physical exertion, I just want to cancel everything. I’d rather stay home. But Lilia reminds me.

“We’re going to look at paintings tomorrow!” she signs.

“Um, yeah,” I say. I try to think of some excuse not to go.

Well, we aren’t really prepared. I was planning on showing her a film I’d bought about Kusama’s life and work. Afterward, I’d imagined I would discuss it with her. I’ve read the artist’s autobiography, Infinity Net. I know that she made macaroni sculptures because she was afraid of food. She created phallic sculptures because she was afraid of sex. I know that due to mental illness, she has lived in a psychiatric hospital in Tokyo for the past thirty years or so. She credits her art with keeping her alive. If she did not paint, she says, she would kill herself. In other words, I’ve done a bit of research about the artist. I have some context. However, Lilia doesn’t. Not yet. Maybe we aren’t ready for this.

Then again, it was me who wanted to see the Kusama exhibit in the first place. If I don’t take advantage of this chance, I’ll regret it later. And how can I allow myself to be lazy? Friends and family older than me are running marathons, for Pete’s sake.

On top of that, my daughter hasn’t been out of the house in three days. It’s partly because I’m too lazy to push her wheelchair. It’s partly because Lilia is too lazy to wheel herself. Kusama, who uses a wheelchair, could be inspiring to Lilia.

Also, Kusama works with simple motifs. Lilia is an aspiring artist herself. Some paintings and drawings make my daughter twist her cheek with her thumb and forefinger. This is the Japanese sign for “difficult.” But Kusama’s art is easy to understand. Lilia could imitate the dots and the line drawings. She could try to glue macaroni onto mannequins. Also, like my daughter, Kusama paints in spite of various challenges.

I want Lilia to understand the many hurdles the artist has had to overcome. As a child, Kusama hallucinated. She heard the voices of flowers and animals. She grew up in a wealthy but dysfunctional family. Her mother forbade her to paint. She did it anyway. She even found a way to go to New York City. In America, she made a name for herself. If Kusama could get herself halfway around the world, we should be able to make it to a museum a couple of hours away.

2

Lately I’ve had to literally drag my daughter out of bed in the mornings. True, Lilia can’t walk. She can’t hear without her cochlear implant. Even so, she is physically capable of getting out of bed all by herself. She can go to the toilet, wash her face, and change her clothes.

During spring break, she has been lazy. I don’t really blame her. But on the morning of our expedition, she is motivated. She rises even before I do. She composes a funky outfit. She wears a black shirt with white polka dots on top. On the bottom, she dons black-and-white striped tights. Her socks are striped with blue and yellow. Perfect, I think, for a viewing of the art of Yayoi Kusama.

Lilia prepares her Hello Kitty rucksack and a handbag. She makes sure that she has her pink wallet, paper and pen, and books to read. She’s ready to go before I am.

I didn’t buy bus tickets in advance, but I manage to get front-row seats. They are the most accessible seats on the bus. Thanks to the Japanese welfare system, Lilia’s fare is half price. We will also be able to get into the museum for free.

When the bus arrives, Lilia hoists herself up the steps. She gets into her seat with little help. I show the driver how to collapse the wheelchair. He stows it in the belly of the bus.

There are few passengers at mid-

morning. The traffic flows freely. It’s sunny, but a bit chilly. Out the window we can see the lush green hills of Naruto. We pass the resort hotels along the beach. We cross the bridge that spans the Naruto Strait. Underneath the bridge, enormous whirlpools form when the tides change.

Next is Awaji Island, with its many onion fields. Finally, we come upon the Akashi Bridge, which connects to Honshu, the largest island in Japan. The glittering city of Kobe sprawls along the coast. It melts into Osaka, our destination.

Once we reach Osaka Station, we approach a cab. I worry that the driver will balk at the wheelchair, but he is kind. “Take your time,” he urges.

I motion Lilia into the backseat. So far, so good. Within minutes, we’re pulling up to the museum. Soon we’re in the lobby, preparing for a look at The Eternity of Eternal Eternity.

3

One might think that Kusama’s works would be inappropriate for children. After all, at one time she was best known for her phallic sculptures and gay porn films. She encouraged nudity in public settings as a form of protest against war. However, most of her paintings and sculptures are, in fact, child-friendly. The artist herself wears a bright red wig and polka-dotted dresses. She seems innocent in spite of her illness. Or perhaps because of it. Much of her work is playful.

Also, children are more likely than most adults to understand a fear of macaroni. In any case, my daughter is not the youngest visitor to the exhibit. Mothers and children in strollers fill the lobby. They share the elevator with us as we descend into the underground museum.

The first gallery features a series drawn in black magic marker on white canvas. It’s entitled Love Forever. I hear a little boy say, “Kowai!” (“That’s scary!”) Is he referring to the centipede-like figures in Morning Waves? Perhaps he’s afraid of the repetition of eyes in The Crowd. At any rate, he gets it. He feels Kusama’s phobia, the fear that led to the work.

The next room is white. It’s filled with giant tulips dotted with large red circles. This is an experiential work entitled With All My Love for the Tulips, I Pray Forever. Lilia is delighted with the surreal space. She enjoys the colors and the giant tulips. I feel as if I’m in a Tim Burton film. We take several pictures, then move on.

Next we look at My Eternal Soul. In this painting, many of the figures that appeared in the black-and-white series return. This time they are in vivid pinks, oranges, yellows, and blues. For a Westerner like me, these colors and images seem joyful. In Japan, where mothers hesitate to dress their children in bright clothes, such hues are unsettling.

Lilia likes the colors. She pauses before the bright paintings. She reads the somewhat baffling titles. Fluttering Flags applies to red banner-like images. This is fairly straightforward. However, the vibrant mood of a pink canvas covered with lushly lashed eyes, a spoon, a purse, a shoe, and women’s profiles contrasts with its somber title, Death Is Inevitable.

My favorite paintings are the self-portraits toward the end of the exhibit. As a foreigner in Japan, I can relate to In a Foreign Country of Blue-Eyed People. This one recalls Kusama’s years in New York in the 1960s. She was a rare Japanese artist among Americans. Red dots cover the face, suggesting disease. Or dis-ease?

Lilia is partial to Gleaming Lights of the Souls. This is another experiential piece. We are invited to enter a small room with mirror-covered walls. Within the walls, dots of light change colors. It gives us the feeling of being among stars or planets in outer space.

Finally, we watch a short documentary about Kusama. There are no subtitles, but Lilia can see the artist at work. She sees the assistant who eases her in and out of her chair. The assistant also helps Kusama to prepare her canvases.

“See?” I want to tell her. “We all need a hand from time to time.” But I don’t want to disturb her concentration. I’m silent and still, letting her take in whatever she can by herself.

On the way home, I feel pleasantly exhausted, but hopeful. The trip was not as arduous as I’d anticipated. I’m also encouraged by Kusama herself, by the fact that she’s found a way to make a living—and to stay alive—through art, in spite of everything.I’m not pushing my daughter toward a career in the fine arts. As a writer, I know how tough it can be. I don’t necessarily expect Lilia to become famous. She doesn’t need to earn money through her drawings or paintings. However, I feel sure that having art in her life will bring her joy and satisfaction. It will enrich her and give her a means of expression.

I’m hoping that with today’s expedition, I’ve pried the world open just a little bit wider for my daughter—and for myself. I start planning future trips in my head. Next, the two of us can go to the islands of the Inland Sea.

4

To celebrate Lilia’s graduation from junior high school, she and I are taking a mother-daughter trip—this time overnight—to Naoshima, an island off the coast of Shikoku.

Naoshima was once used primarily as a site to dump industrial waste. Now it is full of art museums. One of the museums has one of Claude Monet’s famous water lily paintings. Tourists come from all over the world.

Monet admired Japan, and his art is very popular here. His garden in France was designed to look like a Japanese garden. In turn, a garden modeled after the one in France has been constructed farther south in Shikoku, but the painting is on Naoshima. There are no bridges connecting Naoshima to Shikoku. The only way to get there is by ferry. If it’s foggy or the waves are high, the ferry doesn’t run.

I have made a reservation for us at the Benesse House Museum. Each of the ten rooms in the hotel has original artwork and a view of the Seto Inland Sea.

I’ve been planning for us to go by bus, taxi, and then ferry, and to be met by the hotel shuttle bus. This way, Lilia and I will be able to chat in sign language en route. I’ll be able to read and relax. Unfortunately, a light drizzle is predicted for the day of our trip. Dealing with a wheelchair in the rain is never fun. Although I have never driven to the ferry port in Takamatsu before, I decide to go by car.

5