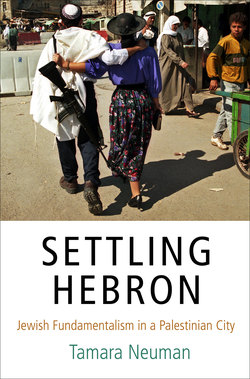

Settling Hebron

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Tamara Neuman. Settling Hebron

Отрывок из книги

Settling Hebron

Tobias Kelly, Series Editor

.....

In order to explain my approach further, let me begin by mapping out key convergences and departures from those of Asad on religion. He understands religious traditions as a way of situating the self with respect to the past from the vantage of the present and contrasts this with secular modern tendencies to look primarily to the future as a form of identification and orientation (Asad 1993, 2003). Asad also reminds us that using the richness of tradition in this way is not the same as being backward. These insights are valuable because they show how uses of tradition entail change; traditions in his view are not “invented” (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983) but always transforming, since they must respond to contemporary challenges in the present, both internal and external, while trying to maintain a general coherence among key defining concepts (Asad 1993). Grappling with changing applications and understandings of a religious tradition for Asad also means rejecting scholars’ use of the category of “fundamentalism” (cf. Marty and Applebee 1991), which he sees as critical of piety more generally, based in part on the accusation of either politicizing or introducing false changes to religion. So Asad would reject the accusation that radical Islam is not true Islam or that settler Judaism is not true Judaism. Using the term “fundamentalism” as a way of characterizing these changes, he and others argue, misrepresents the changing nature of all religious traditions as well as their power dynamics and highlights the lack of reflexivity found in secularist critiques that project irrationality and violence onto religious views alone.

Moreover, Asad rightly points out that there is an important social dimension to religion that cannot be reduced to beliefs alone. He has incisively alerted us to the fact that power and hierarchy shape all religious communities. Asad (1993) also highlights the conditions under which religious “truths” are held to be valid, emphasizing the power dimensions of pedagogy, disciplining the body, and submission to religious authority. Yet in defending a place for religious perspectives and modes of resistance, Asad tends to underplay consolidations of power being ushered in under the sign of religion and the way religious authority can be impervious to critical engagements apart from those offered from within a religious community. Also, in terms of Asad’s explorations of power, he underplays the significance of space (emphasizing the body instead) as the primary medium through which religious subjectivities are shaped and relations of power expressed.11 The social hierarchy that is congealed in the spatial ordering of the built environment, for instance, significantly shapes the ethos of sacred sites and subjective attachments to it in a settler context. Neither involves submission or compliance alone, but they entail direct (and antagonistic) engagements with difference that require the submission of others.

.....