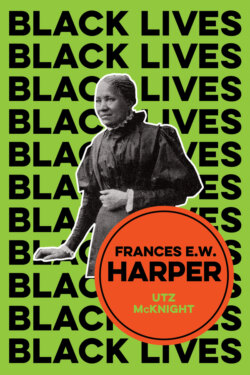

Frances E. W. Harper

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Utz McKnight. Frances E. W. Harper

CONTENTS

Guide

Pages

Black Lives series

Frances E. W. Harper. A Call to Conscience

Preface

1 Frances Harper’s Poetic Journey. A life of consciences

Frances Harper in the 1820s and 1830s

Frances Harper in the 1840 and 1850s

African American print culture

Always free

A private life

Frances Harper in the 1860s and 1870s

Frances Harper in the 1880s, 1890s, and 1900s

2Iola Leroy: Social Equality

The plot

Racial healing

Intimacy

Ways of being

The call to action

White equality

Conclusion

3Trial and Triumph: The Public Demand for Equality. Responsibility and judgment

The plot

Race and public opinion

After slavery

Turning race inside out

Christianity

Conclusion

4Sowing and Reaping: Personal Solutions and Conviction. Complicity

The plot

The vote

The personal is political

Women in private and in the public

The plot

Gender and race at home

Of money and fame

Conclusion. Moral choices

Of the women

5Minnie’s Sacrifice and the Poetic License. Politics

Minnie’s Sacrifice

The plot

The poetry of a people

Nation building

A Black faith

The power of prayer

The common struggle

6 Conclusion: Of Poems and Politics

Mourning

The reader: the call to conscience

Bibliography

Index. A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

R

S

T

U

V

W

Y

POLITY END USER LICENSE AGREEMENT

Отрывок из книги

Elvira Basevich, W. E. B. Du Bois

Utz McKnight, Frances E. W. Harper

.....

The space of the public in which lectures and political speeches occurred was deemed the province of men, and women were to be granted access only exceptionally. Frances Harper was determined to become a regular public speaker, and she succeeded, but not through the direct intervention of her cousin William Watkins Jr., who was involved in the Abolitionist Movement in the New York area (Washington, 2015, p. 71). She participated in the Movement through the organizational efforts of women. She negotiated her moral stance with her audience as she lectured – as a single woman, later when married, and then as a widow after 1864 – and constantly answered for her erudition, as some accused her of not being Black simply because they lacked experience of Black people with an education (Still, 1872, p. 772; Yee, 1992, pp. 112–14).

Andreá Williams argues that Frances Harper, in her capacity as a single woman for much of her public speaking career, modeled the idea of “single blessedness” (Williams, 2014). Alongside the traditional characterization of single women in public as pernicious and immoral was a social capacity to define the single woman as contributing to the sanctity of marriage, through the single woman’s labor in support of this ideal. As Williams points out, the single woman could also be thought of along a continuum from the “kind Aunt who assists her overwhelmed married sister to the unwed churchgoer who masters fundraising” (Williams, 2014, p. 101). The single woman could in this conceptual frame justify in public their assistance of an anti-slavery cause and organization, in support of the moral probity that this political activism represented; they had found a community that, from this perspective, could make positive use of their single status (Williams, 2014, p. 113). As Williams points out, the support that Frances Harper provided for the widow of John Brown after Harpers Ferry falls within this category of the single woman providing assistance to support marriage, where her status as single allows her to aid the widow unconditionally (Still, 1872, p. 763; Williams, 2014, p. 111).

.....