Читать книгу The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 385, August 15, 1829 - Various - Страница 1

HAMPTON COURT

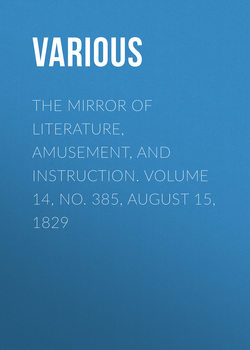

ОглавлениеHere is a bird's-eye view of a royal palace and domain "cut out in little stars." It is copied from one of Kipp's Views in Great Britain in the time of Queen Anne, and affords a correct idea of Hampton Court in all its olden splendour.

The palace is situated on the north bank of the Thames, two miles west from Kingston. It was magnificently built by Cardinal Wolsey. After he became possessed of the lease of the manor of Hampton, "he bestowed," says Stow, "great cost of building upon it, converting the mansion-house into so stately a palace, that it is said to have excited much envy; to avoid which, in the year 1526, he gave it to the king, who in recompense thereof licensed him to lie in his manor of Richmond at his pleasure; and so he lay there at certain times;" but it appears that Wolsey after this occasionally inhabited the palace (perhaps as keeper;) for in 1527, when some French ambassadors were in England, the king sent them to be entertained by the Cardinal at Hampton Court. The preparations for this purpose are detailed in a MS. copy of Cavendish's Life of Wolsey, in the British Museum, and afford the reader some idea of the magnificent taste of the prelate in matters of state and show. The Cardinal was commanded to receive the ambassadors with surpassing splendour; then "my Lord Cardinal sent me (Mr. Cavendish) being his gentleman usher, with two other of my fellows thither, to foresee all things touching our rooms to be nobly garnished"—"accordingly our pains were not small nor light, but daily travelling up and down from chamber to chamber; then wrought the carpenters, joiners, masons, and all other artificers necessary to be had to glorify this noble feast." He tells us of "expert cookes, and connyng persons in the art of cookerie; the cookes wrought both day and night with suttleties and many crafty devices, where lacked neither gold, silver, nor other costly things meet for their purpose"—"280 beds furnished with all manner of furniture to them, too long particularly to be rehearsed, but all wise men do sufficiently know what belongeth to the furniture thereof, and that is sufficient at this time to be said." Wolsey's arrival during the feast is described quaintly enough: "Before the second course my lord came in booted and spurred, all sodainely amongst them proface;1 at whose coming there was great joy, with rising every man from his place, whom my lord caused to sit still, and keep their roomes, and being in his apparel as he rode, called for a chayre and sat down in the middest of the high paradise, laughing and being as merry as ever I saw him in all my lyff." The whole party drank long and strong, some of the Frenchmen were led off to bed, and in the chambers of all was placed abundance of "wine and beere."

Henry VIII. added considerably to Wolsey's building, and in the latter part of his reign, it became one of his principal residences. Among the events connected with the palace are the following:—

Edward VI. was born at Hampton Court, October 12, 1537, and his mother, Queen Jane Seymour, died there on the 14th of the same month.2 Her corpse was conveyed to Windsor by water, where she was buried, November 12. Catharine Howard was openly showed as Queen, at Hampton Court, August 8, 1540. Catharine Parr was married to the King at this palace, and proclaimed Queen, July 12, 1543. In 1558, Mary and Philip kept Christmas here with great solemnity, when the large hall was illuminated with 1,000 lamps. Queen Elizabeth frequently resided, and gave many superb entertainments here, in her reign. In 1603-4, the celebrated conference between Presbyterians and the Established Church was held here before James I. as moderator, in a withdrawing-room within the privy-chamber, on the subject of Conformity. All the Lords of the Council were present, and the conference lasted three days; a new translation of the Bible was ordered, and some alterations were made in the Liturgy.3

Charles I. retired to Hampton Court on account of the plague, in 1625, when a proclamation prohibited all communication between London, Southwark, or Lambeth, and this place.4 Charles was brought here by the army, August 24, 1647, and lived in a state of splendid imprisonment, being allowed to keep up the state and retinue of a court, till November 11, following, when he made his escape5 to the Isle of Wight.

In 1651, the Honour and Palace of Hampton were sold to creditors of the state; but previously to 1657 it came into the possession of Cromwell, who made it one of his chief residences. Elizabeth, his daughter, was here publicly married to the Lord Falconberg; and the Protector's favourite child, Mrs. Claypoole, died here, and was conveyed with great pomp to Westminster Abbey.

The palace was occasionally inhabited by Charles II. and James II. King William resided much at Hampton Court; he pulled down great part of the old palace, which then consisted of five quadrangles, and employed Sir Christopher Wren to build on its site the Fountain Court, or State Apartments. In July, 1689, the Duke of Gloucester, son of the Princess, afterwards Queen Anne, was born here. The Queen sojourned at Hampton occasionally, as did her successors George I. and II.; but George III. never resided here. When his late serene highness William the Fifth, Stadtholder of the United Provinces, was condemned to quit his country by the French, this palace was appropriated to his use; and he resided here several years. The principal domestic apartments of Hampton Court are now occupied by different private families, who have grants for life from the crown.

The palace consists of three grand quadrangles: the western quadrangle, or entrance court is 167 feet 2 inches, north to south, and 141 feet 7 inches, east to west. This leads to the second, or middle quadrangle, 133 feet 6 inches, north to south, and 91 feet 10 inches, east to west; this is usually called the Clock Court, from a curious astronomical clock by Tompion, over the gateway of the eastern side; on the southern side is a colonnade of Ionic pillars by Wren. On the north is the great hall: as this is not mentioned by Cavendish, probably it was part of Henry's building. It certainly was not finished till 1536 or 1537, as appears from initials of the King and Jane Seymour, joined in a true lover's knot, amongst the decorations; this hall is 106 feet long, and 40 broad. Queen Caroline had a theatre erected here, in which it was intended that two plays should be acted weekly during the stay of the Court; but only seven plays were performed in it by the Drury Lane company,6 and one afterwards before the Duke of Lorraine, afterwards Emperor of Germany. The theatrical appurtenances were not, however, removed till the year 1798. Adjoining the hall is the Board of Green Cloth Room, of nearly the same date, and hung with fine tapestry.

The eastern quadrangle, or Fountain Court, erected by Sir Christopher Wren for King William, in 1690, is 100 feet by 177 feet 3 inches. Here is the King's Gallery, 117 feet by 23 feet 6 inches, which was fitted up for the Cartoons of Raphael. On the eastern side of the court is a room in which George I. and George II. frequently dined in public. North-west of the Fountain Court stands the chapel, which forms the southern side of the quadrangle; this was partly built by Wolsey, and was finished by Henry VIII. in 1536, or 1537. The windows were of beautifully stained glass, and the walls decorated with paintings, but these embellishments were demolished in the troublous times of 1745. The chapel was, however, restored by Queen Anne; the floor is of black and white marble, the pews are of Norway oak, and there is some fine carving by Gibbons; the roof is plain Gothic with pendent ornaments.

It is hardly possible for us, within the limits of our columns to do justice to the magnificence of Hampton Court. The grand facade towards the garden extends 330 feet, and that towards the Thames 328 feet. The portico and colonnade, of duplicated pillars of the Ionic order, at the grand entrance, and indeed, the general design of the elevations, are in splendid style. On the south side of the palace is the privy garden, which was sunk ten feet, to open a view from the apartments to the Thames. On the northern side is a tennis court, and beyond that a gate which leads into the wilderness or Maze.7 Further on is the great gate of the gardens.

The gardens, which comprise about 44 acres, were originally laid out by London and Wise. George III. gave the celebrated Brown permission to make whatever improvements his fine taste might suggest; but he declared his opinion that they appeared to the best advantage in their original state, and they accordingly remain so to this day. The extent of the kitchen gardens is about 12 acres. In the privy garden is a grape house 70 feet in length, and 14 in breadth; the interior being wholly occupied by one vine of the black Hamburgh kind, which was planted in the year 1769, and has in a single year, produced 2,200 bunches of grapes, weighing, on an average, one pound each.

The grotesque forms of the gardens, and the mathematical taste in which they are disposed, are advantageously seen in a bird's-eye view as in the Engraving, which represents the tortuous beauty of the parterres, and the pools, fountains, and statues with characteristic accuracy. The formal avenues, radiating as it were, from the gardens or centre, are likewise distinctly shown, as is also the canal formed by Wolsey through the middle avenue. The intervening space, then a parklike waste, is now planted with trees, and stretches away to the village of Thames Ditton; and is bounded on the south by the Thames, and on the north by the high road to Kingston.

The palace is open to the public, and besides its splendid apartments, and numerous buildings, there is a valuable collection of pictures, which are too celebrated to need enumeration. A curious change has taken place in the occupancy of some apartments—many rooms originally intended for domestic offices being now tenanted by gentry. The whole is a vast assemblage of art, and reminds us of the palace of Versailles, which is about the same distance from Paris as Hampton Court from London.

1

An obsolete French term of salutation, abridged from Bon prou vous, i.e. much good may it do you.

2

Stow's Annals.

3

Fuller's Church History.

4

Rymer's Foedera.

5

Clarendon's History of the Rebellion.

6

Cibber tells us that the expenses of each play were £50. and the players were allowed the same sum. The King likewise gave the managers £200. more, for all the performances. For the last play, the actors received £100. One of the plays acted here was Shakspeare's Henry VIII—thus making the palace the scene of Wolseys downfall, as it had been of his splendour.

7

For an Engraving of the Maze, see MIRROR, vol. vi. page 105.