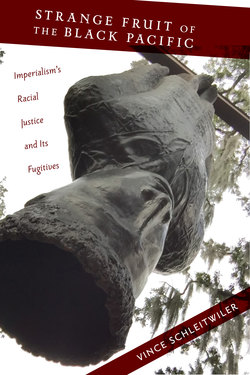

Strange Fruit of the Black Pacific

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Vince Schleitwiler. Strange Fruit of the Black Pacific

Отрывок из книги

STRANGE FRUIT OF THE BLACK PACIFIC

General Editors: Rachel Buff, Matthew Jacobson, and Werner Sollors

.....

This distinction develops through a complex staging of racial and gendered dynamics involving the frustrated romance between Ann Darrow, the beautiful unknown cast by Denham as his film’s lead, and Jack Driscoll, the macho first mate, a committed sailor hesitant around modern women. In an extended sequence after the crew’s initial encounter with the islanders, whose chief had offered six native women to purchase Ann for the still-unidentified Kong, the shooting script shows Ann speculating about Kong’s identity with Charley, who exits suddenly in pursuit of a playful monkey named Ignatz (King Kong shooting script 38–39). On a ship full of men, only the reassuringly asexual cook and the comical simian mascot allow her to relax. The film elides this introduction, getting straight to the dramatic action: a chance encounter on the moonlit deck, where Ann tells Jack the islanders’ drumming has kept her awake. Jack confesses to fearing for her safety, then to fearing her, and finally, to being in love. When she retorts, “You hate women,” he awkwardly replies, “I know, but you aren’t women,” and they kiss. Then, after the captain calls him away, two islanders suddenly appear to kidnap her. Jack returns, finds only Charley, and heads off to her cabin, but then Charley discovers a cowrie bracelet on the deck and sounds the alarm, declaring: “Crazy black man been here!”

The modifier black, in the Chinese cook’s broken English, does not identify the absent kidnapper as African or Negro. Rather, it signifies his racialized capacity to violently assert masculine heterosexual prerogative—unlike Jack or Charley, who are not man enough to act upon their natural desires to possess the white woman. This racialized capacity is merely transferred to the kidnappers as the agents of Kong, to whom the white woman will be offered; at a further remove, it transfers from the islanders to Ann and Jack via the drumming that aurally conditions their previously blocked embrace. While Charley’s own interest in Ann is laughable—in a comic bit of business, he tries to join the search party, waving his meat cleaver and babbling, “Me likey go too. Me likey catch Missy,” before the white men, armed with guns and explosives, wave him away—he provides a cautionary tale for Jack’s white manhood. Just as the decline of Asiatic civilization resulted in emasculated, servile “Chinamen,” Western modernity risked falling into decadence through its supposed disruption of traditional gender roles. The figure of a beautiful young woman, driven by ambition to venture, without husband or father, first to New York City and then to a savage ocean on a boat of rough men, is terrifying enough to send the valiant, virile Jack scampering to the company of other sailors. What might forestall this collapse into decadence is a tonic infusion of primal, violent sexuality, the essence of a blackness embodied by Kong—“neither beast nor man,” Denham puts it, but “monstrous, all-powerful.”

.....