Читать книгу Summit Fever - Andrew Greig - Страница 8

It’s There If You Want It

ОглавлениеA near-stranger makes an outrageous offer 17–23 November 1983

Climbing was something other people did.

I was quite content that it should stay that way, until one wet November evening Mr Malcolm Duff walked in and turned my life upside down.

An evening at home in South Queensferry, idly watching television. Kathleen was reading, the wood stove hissed, the cats twitched in their dreams. Life was domestic, cosy and safe – and just a little boring. But what else could we expect? Then a sharp bang on the window made us start. Enter Malcolm: alert, weathered, impelled by restless energy. We’d met briefly twice and he’d reminded me of an army officer who was contemplating becoming an anarchist. He seemed, as always, to be in a hurry; a brief Hi and he went straight to the point.

‘It’s there if you want it, Andy.’

I looked at him blankly. ‘What’s there?’

‘The Karakoram trip. The Expedition will buy any gear you need, pay your flight out and any expenses. What you do is climb on the Mustagh Tower with us and write a book about the trip. Rocky’s really keen on the idea.’ He prowled restlessly round our kitchen. ‘Well, what do you think?’

I couldn’t think. I was running hot and cold together inside, like a mixer tap. Turning away, registering what had been offered yet unable to take it in, I went through the motions of making coffee, asked if he took sugar. That was how little we knew each other. I remembered now a drunken evening over my home-brew, how he’d said he’d liked my book of narrative climbing poems, Men On Ice, that he was going on an expedition to Pakistan. And I’d made some non-sober, non-serious remark about how it would be interesting to go on a mountaineering trip and write about it. And he’d said he would phone a man called Rocky Moss who was financing the climb …

‘Er, Malcolm … you do realize my book was purely metaphorical? I can’t climb.’

For a moment he looked taken aback. ‘I’ll teach you. No problem.’

‘And I’m scared of heights. They make me feel ill.’

‘You’ll get used to it.’

‘To heights, or feeling ill?’

‘Both.’ The sardonic – satanic – grin was to become all too familiar.

‘It’s just …’ Just what? Wonderful? Outrageous. Exciting? Stunning. I played for time and said I’d need to think about it.

‘Sure,’ he replied. We leaned against the fridge and chatted for a few minutes. I wasn’t taking in much. He drained his coffee, stubbed his cigarette and made for the door. ‘Let me know inside a week.’ Then he paused, grinned. ‘Go for it, youth,’ he said, and was gone.

Leaving me sweating, staring through the steam of my mug at a mountain I’d never seen or even heard of – the Somethingorother Tower – waiting for me on the other side of the world. A week to decide.

What does an armchair climber feel when offered the chance to turn daydream into reality? Incredulity. Euphoria. Panic. Suddenly the routines of ordinary life seem deeply reassuring and desirable. Why leave them? Familiar actions and satisfactions may at times seem bland, but they are sustaining. Armchair daydreams are the salt that gives them savour, nothing more.

And yet …

I talked it round and round that evening with Kathleen. She was torn between envy and worry. She didn’t want me to go. She wanted to go herself. I didn’t know what I wanted. If I stayed to finish a radio play – about two climbers, as irony would have it – we could afford to go somewhere interesting, hot and safe.

As we talked it out, I wondered how often this scene had been enacted. It’s the one the adventure books always omit. Conflicting desires and loyalties, leaving someone behind. Any adventurer who is not a complete hermit must go through that scene. It makes some apparently callous and ruthlessly clear about where their priorities lie.

I had none of that certainty. Yet how could one turn down an offer like this?

‘Try saying No,’ Kathleen suggested.

I phoned Malcolm the next evening to say I hadn’t made up my mind but maybe it would be a good idea for me to find out more about the Expedition. Such as what, where and who. At the end of five minutes my head was spinning and my notepad was crosshatched with names, dates and places, and some alarming vertical doodles.

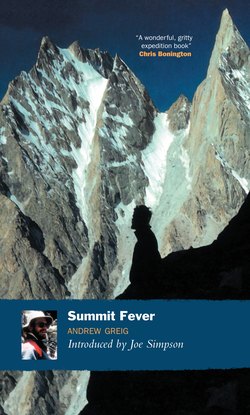

The mountain was called the Mustagh Tower. It had been climbed only twice, and that twenty-eight years ago; we were going for the Joe Brown–Tom Patey route. I tried to make knowledgeable, approving noises. It was just under 24,000 feet high, in the Karakoram which were apparently part of the Himalayas, ‘third turning on the left before K2’. At least I’d heard of that.

We’d be leaving in June, for two or three months. Our second objective was called Gasherbrum 2, some 26,000 feet high. I was pleased to hear I wasn’t expected to do anything on it. That ‘gash’ bit sounded vicious, and the ‘brum’ was resonant with avalanche. At the moment there were four British lead climbers, a doctor and myself, four Nepalese Sherpas and three Americans whose experience was limited largely to being guided. One of them was the intriguing Rocky Moss who was paying for the trip. I wondered what he had against writers. The plan was to fix ropes on the steep section up to a col at 21,000 feet – that would be my summit – then the lead climbers would try to finish the route, establishing one or two more camps on the way, and the Sherpas would give the less experienced climbers a chance of the top. No oxygen, except two cylinders at Base Camp for emergency medical use. An American Slave, to serve us at Base Camp.

Even from my limited reading of mountaineering books, it sounded a very strange expedition, more like a circus. I’d never heard of anyone being guided up a demanding Himalayan peak.

I sat by the fire, frowning at the notepad and trying to memorize the jumble of figures, names and places. They all sounded vague, unlikely, entirely fanciful. Yet these names could acquire faces, the places could be all around me, and they could all become part of the most powerful experience of my life. The rap on the window, the surfeit of home-brew, my book of metaphorical climbers, could propel me into the one great adventure we all daydream about.

Or into fiasco, failure, or worse.

A week to decide. The world outside me went on, but neglected as a flickering TV during a barroom brawl. I went through the motions of living and working, blind to everything but my inner debate. A couple of climbing acquaintances eagerly filled me in on the quite astonishing variety of ways of croaking in the Himalayas. Falling off the mountain seemed the least of my worries. Strokes, heart attacks, pulmonary oedema, cerebral oedema, frostbite, exposure, pneumonia, stone fall, avalanche, crevasse, mountain torrents and runaway yaks – each with a name and an instance of someone who had been killed that way. Climbers seemed to love good death-and-destruction stories, and at first their humour appears callous and ghoulish.

I could picture them all, every one. My fingers turned black from frostbite while clenching a fork, ropes parted as I pegged out the washing. I stood on the col bringing in the milk, then was bundled into oblivion by avalanche as I let in the cat. I chided myself for being melodramatic; the truth was I had no idea what I was up against. All I knew was that many people had died in many ways in the Himalayas – how prepared I was to take a chance on it? Life was too pleasant and interesting to lose, yet to turn down an experience like this …

My enthusiasm diminished noticeably by nightfall. By the time I lay in bed, exhausted by visions of blizzards, bottomless crevasses, collapsing cornices, avalanche, it was clear I wouldn’t go. The only realistic decision. I was not a climber, nor meant to be.

In the morning, contemplating another quiet day at the typewriter set against the adventure of a lifetime in the great mountains of the world, it was obvious: go, you fool. Enough shifting words around a ghostly inner theatre. I’d always hungered after one big adventure. Then I’d come home, hang up my ice axe and put my boots in the loft. There was some risk, but that was the condition of adventure. It seemed inevitable that I’d end up going.

On the evening of 20 November, Kathleen threw an I Ching hexagram.

‘This is uncanny. Want to see?’

I looked at the reading:

Hexagram 62. Hsiao Kuo: Preponderance of the small.

Success. Perseverance furthers.

Small things may be done; great things should not be done.

It is not well to strive upward,

it is well to remain below.

My eye skipped on

…. Thunder on the mountain. Thunder in the mountains

sounds much nearer.

I put down the book, thought about it. ‘Were you asking about yourself or me?’

‘Both of us.’

‘Doesn’t pull any punches, does it?’

Silence from Kathleen. Then, quietly, ‘Please don’t go.’

I visited a climbing acquaintance to sound out his opinion. My wellbeing and safety rested largely on Mal Duff’s judgement and abilities. I scarcely knew him as a person, and not at all as a climber. What was his reputation in the climbing world?

‘Mal Duff? Can’t say I know him that well. A lot of people would put a question mark beside his name, but I don’t know why. Envy, maybe – he’s one of the very few who almost make a living from climbing. There was some kind of financial screw- up … No one’s ever suggested he can’t climb.’

I accepted a whisky and let him talk on. The climbing world appeared very intense, gossipy yet reticent, full of allegiances and rivalries. I was just beginning to learn to read the coded messages, and to try to sort out a sound assessment from bias.

‘He’s done a lot in Scotland in winter, some in the Alps. I think he was out on Nuptse twice, so he’s had some Himalayan experience. He’s possibly not as good as he thinks he is – but nor am I! I’ve heard of this other chap, Sandy Allan, but the rest of the Brit climbers mean nothing to me. The Mustagh Tower is a classic – did you know it was once called “the unclimbable mountain” and “the Himalayan Matterhorn”? – but it sounds a very odd expedition with these semi-climbers along. I’d be very surprised if anyone gets to the top.’

I nodded, looked into the bottom of my glass. How much of what I was hearing was envy? How much was climbing bullshit and how much accurate assessment? We talked a while longer about Malcolm and the trip – in that warm, Edinburgh flat it all seemed extremely hypothetical – till I asked the obvious question: is it possible for someone with as yet no mountaineering experience at all to go to 21,000 feet on a Himalayan peak?

‘Yes, it’s possible. Whether it’s desirable …’ He laughed, seemed to find the whole project amusing. But then he’d found being shipwrecked off Patagonia amusing. He’d obviously lost a few brain cells along the way. ‘Yes, if you’re very fit, can take the altitude, have considerable determination and are lucky – ’

‘That doesn’t sound like me at all,’ I interrupted him.

‘– there’s no reason why not. It may blow your mind a bit, but you’ll be safer than you think. Mind you, the Himalayas make the Alps look like a kiddies’ playground – but you’ve never seen the Alps, have you? And of course,’ he continued, smiling, ‘if something doesn’t go according to plan – and that’s bound to happen – you could be in real trouble. You’ve maybe one chance in twenty of snuffing it.’

We had another whisky and I looked over the photos on his wall. Douglas crawling beneath stomach-turning overhangs, Douglas on Patagonian mountains, Douglas and friends steering a 12-foot inflatable through a Greenland ice pack. A lump of quartz from a Patagonian first ascent. Mementoes of another world. Nice to have some souvenirs like that …

It’s the little vanities that get us going.

‘The trip’s a freebie,’ Douglas said. ‘Take it.’

After five days of indecision – or rather, of constantly changing decisions – I went home to Anstruther to talk it over with my parents. I wanted to hear their opinion; perhaps that would clarify my thoughts.

So, should I go?

Dad paused so long I thought he hadn’t heard me properly. A long, awkward silence, my mother at the other end of the table, waiting for his response. Then he said very slowly, ‘I’m too old to be asked a question like that.’ He looked at me, his eyes pale blue and slightly fogged over, set deep among the ridges, wrinkles, creases and weathering of eighty-four years. ‘You see,’ he said simply, ‘I can no longer see any appeal in experience for its own sake.’

How had I failed to see how old, how very, very tired he’d become in the last year? The hand that held the glass of wine had shrunk to skin and bone. He took a sip, grimaced. ‘I’ve even lost the taste for this. But in your position, at your age … Yes, you should go.’

Then he began to pull out from the vast, shadowy storehouse of his memory bales of stories of scrambling in the Cairngorms as a medical student in the 1920s, seeing the colossal Grey Man of Ben MacDui, the early days of the Scottish Youth Hostel movement, escapades in Ardnamurchan, taking the first motorcar over the old drove road to Applecross, hurrying five miles across a snowbound moor in the dead of winter to deliver a baby in an Angus bothy …

And vitality came back to him like a fitful companion as he talked, and I sensed it was all happening again for him, behind the eyes of this most unsentimental of men. It had been these tales, together with his recollections of dawns in Sumatra and hurricanes in the China Seas, that had first made me long for my own adventures, for those experiences of youth that nothing, not even extreme old age, can take away from you as long as you breathe.

Listening to him confirmed in me what I’d always known. When it came down to it, I’d take the chance.

‘Are you thinking what I’m thinking, Kath?’

‘Yes.’

Pause. Me leaning on the door frame, her grinning on the settee.

‘We’re going then?’

‘Yes.’

And that was the decision made, in an instant, on an impulse. The impulse of life that says, ‘Why not?’

Mal had just gone out the door, and taken most of my reservations with him. He’d filled us in on more details, and they were largely reassuring. He’d promised my Glencoe initiation would not be terminal. I was very aware that my life would depend largely on his priorities and his judgement; in the end, on his character. I’d been watching and listening to him closely. I’d liked him from the start for his great enthusiasm for life. He was interested in practically everything, not just climbing. Now I sensed behind the casualness considerable determination. Behind the romantic was a hard-nosed realist. Behind the restless energy that kept his fingers tap-tapping a cigarette and his right knee jumping as he sat, there was a sense of self-possession. These were not nervous mannerisms, but those of someone who revved his way through life. The sardonic grin, the offhand climber’s humour, the thoughtful frown into the mug of coffee – they all seemed in balance with each other.

He struck me as the kind of person who might get you into scrapes but would probably get you out of them again. (And how prophetic that turned out to be!)

I’d trust him.

A deciding factor was Kathleen’s inclusion. She asked if she could come along with the trekking group who were to accompany us on the walk-in to Mustagh, and cover her costs through writing articles about her trip. Just flying a kite … Mal took it quite seriously and said he saw no reason why not, subject to Rocky’s agreement.

We hadn’t actually said Yes to him but, grinning wildly at each other, we knew we’d decided.

The world was transformed. Being alive felt dramatized and vivid, vibrant with challenge. We couldn’t sit still. Adrenalin propelled us outdoors into a mild November night. We walked fast and aimlessly past moonlit stubble fields, dark cottages, a hunched country church. An owl glided between us and the moon. An omen? The night felt huge and elating as we talked, half giggling, spilling out plans, images, anticipations and fears.

It was like being a teenager again. The same pumped-up energy, the fancies and fantasies swirling through the body, the sense of the world being wide open and there to be explored. The ordinary things around us seemed vivid and precious, shining as the map Kathleen drew with a finger dipped in beer on a polished table in the Hawes Inn that night. ‘Here is Pakistan,’ she said, ‘and here’s Islamabad where we fly to.’ She wetted her finger again and drew a squiggly line. ‘And here, I think, are the Karakoram.’

We sat and stared at the table, silent for a minute as the crude map of our future shone then faded.