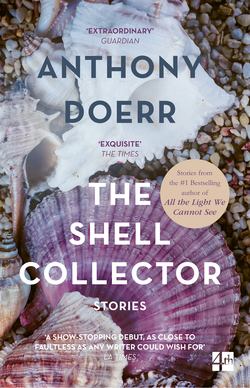

Читать книгу The Shell Collector - Anthony Doerr, Anthony Doerr - Страница 8

THE HUNTER’S WIFE

ОглавлениеIt was the hunter’s first time outside of Montana. He woke, stricken still with the hours-old vision of ascending through roselit cumulus, of houses and barns like specks deep in the snowed-in valleys, all the scrolling country below looking December—brown and black hills streaked with snow, flashes of iced-over lakes, the long braids of a river gleaming at the bottom of a canyon. Above the wing the sky had deepened to a blue so pure he knew it would bring tears to his eyes if he looked long enough.

Now it was dark. The airplane descended over Chicago, its galaxy of electric lights, the vast neighborhoods coming clearer as the plane glided toward the airport—streetlights, headlights, stacks of buildings, ice rinks, a truck turning at a stoplight, scraps of snow atop a warehouse and winking antennae on faraway hills, finally the long converging parallels of blue runway lights, and they were down.

He walked into the airport, past the banks of monitors. Already he felt as if he’d lost something, some beautiful perspective, some lovely dream fallen away. He had come to Chicago to see his wife, whom he had not seen in twenty years. She was there to perform her magic for a higher-up at the state university. Even universities, apparently, were interested in what she could do.

Outside the terminal the sky was thick and gray and hurried by wind. Snow was coming. A woman from the university met him and escorted him to her Jeep. He kept his gaze out the window.

They were in the car for forty-five minutes, passing first the tall, lighted architecture of downtown, then naked suburban oaks, heaps of ploughed snow, gas stations, power towers and telephone wires. The woman said, So you regularly attend your wife’s performances?

No, he said. Never before.

She parked in the driveway of an elaborate and modern mansion with square balconies suspended at angles over two trapezoidal garages, huge triangular windows in the facade, sleek columns, domed lights, a steep shale roof.

Inside the front door about thirty name tags were laid out on a table. His wife was not there yet. No one, it seemed, was there yet. He found his tag and pinned it to his sweater. A silent girl in a tuxedo appeared and disappeared with his coat.

The foyer was all granite, flecked and smooth, backed with a grand staircase that spread wide at the bottom and tapered at the top. A woman came down. She stopped four or five steps from the bottom and said, Hello, Anne, to the woman who had driven him there and, You must be Mr. Dumas, to him. He took her hand, a pale bony thing, weightless, like a featherless bird.

Her husband, the university’s chancellor, was just knotting his bow tie, she said, and laughed sadly to herself, as if bow ties were something she disapproved of. Beyond the foyer spread a vast parlor, high-windowed and carpeted. The hunter moved to a bank of windows, shifted aside the curtain and peered out.

In the poor light he could see a wooden deck encompassing the length of the house, angled and stepped, never the same width, with a low rail. Beyond it, in the blue shadows, a small pond lay encircled by hedges, with a marble birdbath at its center. Behind the pond stood leafless trees—oaks, maples, a sycamore white as bone. A helicopter shuttled past, winking a green light.

It’s snowing, he said.

Is it? asked the hostess, with an air of concern, perhaps false. It was impossible to tell what was sincere and what was not. The woman who drove him there had moved to the bar where she cradled a drink and stared into the carpet.

He let the curtain fall back. The chancellor came down the staircase. Other guests fluttered in. A man in gray corduroy, with BRUCE MAPLES on his name tag, approached him. Mr. Dumas, he said, your wife isn’t here yet?

You know her? the hunter asked. Oh no, Maples said, and shook his head. No I don’t. He spread his legs and swiveled his hips as if stretching before a foot race. But I’ve read about her.

The hunter watched as a tall, remarkably thin man stepped through the front door. Hollows behind his jaw and beneath his eyes made him appear ancient and skeletal—as if he were visiting from some other leaner world. The chancellor approached the thin man, embraced him, and held him for a moment.

That’s President O’Brien, Maples said. A famous man, actually, to people who follow those sorts of things. So terrible, what happened to his family. Maples stabbed the ice in his drink with his straw.

The hunter nodded, unsure of what to say. For the first time he began to think he should not have come.

Have you read your wife’s books? Maples asked.

The hunter nodded.

In her poems her husband is a hunter.

I guide hunters. He was looking out the window to where snow was settling on the hedges.

Does that ever bother you?

What?

Killing animals. For a living, I mean.

The hunter watched snowflakes disappear as they touched the window. Was that what hunting meant to people? Killing animals? He put his fingers to the glass. No, he said. It doesn’t bother me.

The hunter met his wife in Great Falls, Montana, in the winter of 1972. That winter arrived immediately, all at once—you could watch it come. Twin curtains of white appeared in the north, white all the way to the sky, driving south like the end of all things. They drove the wind before them and it ran like wolves, like floodwater through a cracked dyke. Cattle galloped the fencelines, bawling. Trees toppled; a barn roof tumbled over the highway. The river changed directions. The wind flung thrushes screaming into the gorge and impaled them on the thorns in grotesque attitudes.

She was a magician’s assistant, beautiful, sixteen years old, an orphan. It was not a new story: a glittery red dress, long legs, a traveling magic show performing in the meeting hall at the Central Christian Church. The hunter had been walking past with an armful of groceries when the wind stopped him in his tracks and drove him into the alley behind the church. He had never felt such wind; it had him pinned. His face was pressed against a low window, and through it he could see the show. The magician was a small man in a dirty blue cape. Above him a sagging banner read THE GREAT VESPUCCI. But the hunter watched only the girl; she was graceful, young, smiling. Like a wrestler the wind held him against the window.

The magician was buckling the girl into a plywood coffin that was painted garishly with red and blue bolts of lightning. Her neck and head stuck out one end, her ankles and feet the other. She beamed; no one had ever before smiled so broadly at being locked into a coffin. The magician started up an electric saw and brought it noisily down through the center of the box, sawing her in half. Then he wheeled her apart, her legs going one way, her torso another. Her neck fell back, her smile waned, her eyes showed only white. The lights dimmed. A child screamed. Wiggle your toes, the magician ordered, flourishing his magic wand, and she did; her disembodied toes wiggled in glittery high-heeled pumps. The audience squealed with delight.

The hunter watched her pink fine-boned face, her hanging hair, her outstretched throat. Her eyes caught the spotlight. Was she looking at him? Did she see his face pressed against the window, the wind slashing at his neck, the groceries—onions, a sack of flour—tumbled to the ground around his feet? Her mouth flinched; was it a smile, a flicker of greeting?

She was beautiful to him in a way that nothing else had ever been beautiful. Snow blew down his collar and drifted around his boots. The wind had fallen off but the snow came hard and still the hunter stood riveted at the window. After some time the magician rejoined the severed box halves, unfastened the buckles, and fluttered his wand, and she was whole again. She climbed out of the box and curtsied in her glittering slit-legged dress. She smiled as if it were the Resurrection itself.

Then the storm brought down a pine tree in front of the courthouse and the power winked out, streetlight by streetlight, all over town. Before she could move, before ushers began escorting the crowd out with flashlights, the hunter was slinking into the hall, making for the stage, calling for her.

He was thirty years old, twice her age. She smiled at him, leaned over from the dais in the red glow of the emergency exit lights and shook her head. Show’s over, she said. In his pickup he trailed the magician’s van through the blizzard to her next show, a library fund-raiser in Butte. The next night he followed her to Missoula. He rushed to the stage after each performance. Just eat dinner with me, he’d plead. Just tell me your name. It was hunting by persistence. She said yes in Bozeman. Her name was plain, Mary Roberts. They had rhubarb pie in a hotel restaurant.

I know how you do it, he said. The feet in the sawbox are dummies. You hold your legs against your chest and wiggle the dummy feet with a string.

She laughed. Is that what you do? she asked. Follow a girl to four towns to tell her her magic isn’t real?

No, he said. I hunt.

You hunt. And when you’re not hunting?

I dream about hunting. She laughed again. It’s not funny, he said.

You’re right, she said, and smiled. It’s not funny. I’m that way with magic. I dream about it. I dream about it all the time. Even when I’m not asleep.

He looked into his plate, thrilled. He searched for something he might say. They ate. But I dream bigger dreams, you know, she said afterward, after she had eaten two pieces of pie, carefully, with a spoon. Her voice was quiet and serious. I have magic inside of me. I’m not going to get sawed in half by Tony Vespucci all my life.

I don’t doubt it, the hunter said.

I knew you’d believe me, she said.

But the next winter Vespucci brought her back to Great Falls and sawed her in half in the same plywood coffin. And the winter after that. After both performances the hunter took her to the Bitterroot Diner where he watched her eat two pieces of pie. The watching was his favorite part: a hitch in her throat as she swallowed, the way the spoon slid cleanly out from her lips, the way her hair fell over her ear.

Then she was eighteen, and after pie she let him drive her to his cabin, forty miles from Great Falls, up the Missouri, then east into the Smith River valley. She brought only a small vinyl purse. The truck skidded and sheered as he steered it over the unploughed roads, fishtailing in the deep snow, but she didn’t seem afraid or worried about where he might be taking her, about the possibility that the truck might sink in a drift, that she might freeze to death in her pea coat and glittery magician’s-assistant dress. Her breath plumed out in front of her. It was twenty degrees below zero. Soon the roads would be snowed over, impassable until spring.

At his one-room cabin with furs and old rifles on the walls, he unbolted the crawlspace and showed her his winter hoard: a hundred smoked trout, skinned pheasant and venison quarters hanging frozen from hooks. Enough for two of me, he said. She scanned his books over the fireplace, a monograph on grouse habits, a series of journals on upland game birds, a thick tome titled simply Bear. Are you tired? he asked. Would you like to see something? He gave her a snowsuit, strapped her boots into a pair of leather snowshoes, and took her to hear the grizzly.

She wasn’t bad on snowshoes, a little clumsy. They went creaking over wind-scalloped snow in the nearly unbearable cold. The bear denned every winter in the same hollow cedar, the top of which had been shorn off by a storm. Black, three-fingered and huge, in the starlight it resembled a skeletal hand thrust up from the ground, a ghoulish visitor scrabbling its way out of the underworld.

They knelt. Above them the stars were knife points, hard and white. Put your ear here, he whispered. The breath that carried his words crystallized and blew away, as if the words themselves had taken on form but expired from the effort. They listened, face-to-face, their ears over woodpecker holes in the trunk. She heard it after a minute, tuning her ears into something like a drowsy sigh, a long exhalation of slumber. Her eyes widened. A full minute passed. She heard it again.

We can see him, he whispered, but we have to be dead quiet. Grizzlies are light hibernators. Sometimes all you do is step on twigs outside their dens and they’re up.

He began to dig at the snow. She stood back, her mouth open, eyes wide. Bent at the waist, he bailed snow back through his legs. He dug down three feet and then encountered a smooth icy crust covering a large hole in the base of the tree. Gently he dislodged plates of ice and lifted them aside. The opening was dark, as if he’d punched through to some dark cavern, some netherworld. From the hole the smell of bear came to her, like wet dog, like wild mushrooms. The hunter removed some leaves. Beneath was a shaggy flank, a brown patch of fur.

He’s on his back, the hunter whispered. This is his belly. His forelegs must be up here somewhere. He pointed to a place higher on the trunk.

She put one hand on his shoulder and knelt in the snow above the den. Her eyes were wide and unblinking. Her jaw hung open. Above her shoulder a star separated itself from the galaxy and melted through the sky. I want to touch him, she said. Her voice sounded loud and out of place in that wood, under the naked cedars.

Hush, he whispered. He shook his head no. You have to speak quietly.

Just for a minute.

No, he hissed. You’re crazy. He tugged at her arm. She removed the mitten from her other hand with her teeth and reached down. He pulled at her again but lost his footing and fell back, clutching an empty mitten. As he watched, horrified, she turned and placed both hands, spread-fingered, in the thick shag of the bear’s chest. Then she lowered her face, as if drinking from the snowy hollow, and pressed her lips to the bear’s chest. Her entire head was inside the tree. She felt the soft, silver tips of its fur brush her cheeks. Against her nose one huge rib flexed slightly. She heard the lungs fill and then empty. She heard blood slug through veins.

Want to know what he dreams? she asked. Her voice echoed up through the tree and poured from the shorn ends of its hollowed branches. The hunter took his knife from his coat. Summer, her voice echoed. Blackberries. Trout. Dredging his flanks across river pebbles.

I’d have liked, she said later, back in the cabin as he built up the fire, to crawl all the way down there with him. Get into his arms. I’d grab him by the ears and kiss him on the eyes.

The hunter watched the fire, the flames cutting and sawing, each log a burning bridge. Three years he had waited for this. Three years he had dreamed this girl by his fire. But somehow it had ended up different from what he had imagined; he had thought it would be like a hunt—like waiting hours beside a wallow with his rifle barrel on his pack to see the huge antlered head of a bull elk loom up against the sky, to hear the whole herd behind him inhale, then scatter down the hill. If you had your opening you shot and walked the animal down and that was it. All the uncertainty was over. But this felt different, as if he had no choices to make, no control over any bullet he might let fly or hold back. It was exactly as if he was still three years younger, stopped outside the Central Christian Church and driven against a low window by the wind or some other, greater force.

Stay with me, he whispered to her, to the fire. Stay the winter.

Bruce Maples stood beside him jabbing the ice in his drink with his straw.

I’m in athletics, Bruce offered. I run the athletic department here.

You mentioned that.

Did I? I don’t remember. I used to coach track. Hurdles.

Hurdles, the hunter repeated.

You bet.

The hunter studied him. What was Bruce Maples doing here? What strange curiosities and fears drove him, drove any of these people filing now through the front door, dressed in their dark suits and black gowns? He watched the thin, stricken man, President O’Brien, as he stood in the corner of the parlor. Every few minutes a couple of guests made their way to him and took O’Brien’s hands in their own.

You probably know, the hunter told Maples, that wolves are hurdlers. Sometimes the people who track them will come to a snag and the prints will disappear. As if the entire pack just leaped into a tree and vanished. Eventually they’ll find the tracks again, thirty or forty feet away. People used to think it was magic—flying wolves. But all they did was jump. One great coordinated leap.

Bruce was looking around the room. Huh, he said. I wouldn’t know about that.

She stayed. The first time they made love, she shouted so loudly that coyotes climbed onto the roof and howled down the chimney. He rolled off her, sweating. The coyotes coughed and chuckled all night, like children chattering in the yard, and he had nightmares. Last night you had three dreams and you dreamed you were a wolf each time, she whispered. You were mad with hunger and running under the moon.

Had he dreamed that? He couldn’t remember. Maybe he talked in his sleep.

In December it never got warmer than fifteen below. The river froze—something he’d never seen. Christmas Eve he drove all the way to Helena to buy her figure skates. In the morning they wrapped themselves head to toe in furs and went out to skate the river. She held him by the hips and they glided through the blue dawn, skating hard up the frozen coils and shoals, beneath the leafless alders and cottonwoods, only the bare tips of creek willow showing above the snow. Ahead of them vast white stretches of river faded on into darkness. An owl hunkered on a branch and watched them with its huge eyes. Merry Christmas, Owl! she shouted into the cold. It spread its huge wings, dropped from the branch and disappeared into the forest.

In a wind-polished bend they came upon a dead heron, frozen by its ankles into the ice. It had tried to hack itself out, hammering with its beak first at the ice entombing its feet and then at its own thin and scaly legs. When it finally died, it died upright, wings folded back, beak parted in some final, desperate cry, legs rooted like twin reeds in the ice.

She fell to her knees and knelt before the bird. Its eye was frozen and cloudy. It’s dead, the hunter said, gently. Come on. You’ll freeze too.

No, she said. She slipped off her mitten and closed the heron’s beak in her fist. Almost immediately her eyes rolled back in her head. Oh wow, she moaned. I can feel her. She stayed like that for whole minutes, the hunter standing over her, feeling the cold come up his legs, afraid to touch her as she knelt before the bird. Her hand turned white and then blue in the wind.

Finally she stood. We have to bury it, she said. He chopped the bird out with his skate and buried it in a drift.

That night she lay stiff and would not sleep. It was just a bird, he said, unsure of what was bothering her but bothered by it himself. We can’t do anything for a dead bird. It was good that we buried it, but tomorrow something will find it and dig it out.

She turned to him. Her eyes were wide; he remembered how they had looked when she put her hands on the bear. When I touched her, she said, I saw where she went.

What?

I saw where she went when she died. She was on the shore of a lake with other herons, a hundred others, all facing the same direction, and they were wading among stones. It was dawn and they watched the sun come up over the trees on the other side of the lake. I saw it as clearly as if I was there.

He rolled onto his back and watched shadows shift across the ceiling. Winter is getting to you, he said. In the morning he resolved to make sure she went out every day. It was something he’d long believed: go out every day in winter or your mind will slip. Every winter the paper was full of stories about ranchers’ wives, snowed in and crazed with cabin fever, who had dispatched their husbands with cleavers or awls.

The next night he drove her all the way north to Sweetgrass, on the Canadian border, to see the northern lights. Great sheets of violet, amber and pale green rose from the distances. Shapes like the head of a falcon, a scarf and a wing rippled above the mountains. They sat in the truck cab, the heater blowing on their knees. Behind the aurora the Milky Way burned.

That one’s a hawk! she exclaimed.

Auroras, he explained, occur because of Earth’s magnetic field. A wind blows all the way from the sun and gusts past the earth, moving charged particles around. That’s what we see. The yellow-green stuff is oxygen. The red and purple at the bottom there is nitrogen.

No, she said, shaking her head. The red one’s a hawk. See his beak? See his wings?

Winter threw itself at the cabin. He took her out every day. He showed her a thousand ladybugs hibernating in an orange ball hung in a riverbank hollow; a pair of dormant frogs buried in frozen mud, their blood crystallized until spring. He pried a globe of honeybees from its hive, slow-buzzing, stunned from the sudden exposure, each bee shimmying for warmth. When he placed the globe in her hands she fainted, her eyes rolled back. Lying there she saw all their dreams at once, the winter reveries of scores of worker bees, each one fiercely vivid: bright trails through thorns to a clutch of wild roses, honey tidily brimming a hundred combs.

With each day she learned more about what she could do. She felt a foreign and keen sensitivity bubbling in her blood, as though a seed planted long ago was just now sprouting. The larger the animal, the more powerfully it could shake her. The recently dead were virtual mines of visions, casting them off with a slow-fading strength like a long series of tethers being cut, one by one. She pulled off her mittens and touched everything she could: bats, salamanders, a cardinal chick tumbled from its nest, still warm. Ten hibernating garter snakes coiled beneath a rock, eyelids sealed, tongues stilled. Each time she touched some frozen insect, some slumbering amphibian, anything just dead, her eyes rolled back and its visions, its heaven, went shivering through her body.

Their first winter passed like that. When he looked out the cabin window he saw wolf tracks crossing the river, owls hunting from the trees, six feet of snow like a quilt ready to be thrown off. She saw burrowed dreamers nestled under the roots against the long twilight, their dreams rippling into the sky like auroras.

With love still lodged in his heart like a splinter, he married her in the first muds of spring.

Bruce Maples gasped when the hunter’s wife finally arrived. She moved through the door like a show horse, demure in the way she kept her eyes down but assured in her step; she brought each tapered heel down and struck it against the granite. The hunter had not seen his wife for twenty years, and she had changed—become refined, less wild, and somehow, to the hunter, worse for it. Her face had wrinkled around the eyes, and she moved as if avoiding contact with anything near her, as if the hall table or closet door might suddenly lunge forward to snatch at her lapels. She wore no jewelry, no wedding ring, only a plain black suit, double-breasted.

She found her name tag on the table and pinned it to her lapel. Everyone in the reception room looked at her then looked away. The hunter realized that she, not President O’Brien, was the guest of honor. In a sense they were courting her. This was their way, the chancellor’s way—a silent bartender, tuxedoed coat girls, big icy drinks. Give her pie, the hunter thought. Rhubarb pie. Show her a sleeping grizzly.

They sat for dinner at a narrow and very long table, fifteen or so high-backed chairs down each side and one at each head. The hunter was seated several places away from his wife. She looked over at him finally, a look of recognition, of warmth, and then looked away again. He must have seemed old to her—he must always have seemed old to her. She did not look at him again.

The kitchen staff, in starched whites, brought onion soup, scampi, poached salmon. Around the hunter guests spoke in half whispers about people he did not know. He kept his eyes on the windows and the blowing snow beyond.

The river thawed and drove huge saucers of ice toward the Missouri. The sound of water running, of release, of melting, clucked and purled through the open windows of the cabin. The hunter felt that old stirring, that quickening in his soul, and he would rise in the wide pink dawns, take his fly rod and hurry down to the river. Already trout were rising through the chill brown water to take the first insects of spring. Soon the telephone in the cabin was ringing with calls from clients, and his guiding season was on.

Occasionally a client wanted a lion or a trip with dogs for birds, but late spring and summer were for trout. He was out every morning before dawn, driving with a thermos of coffee to pick up a lawyer, a widower, a politician with a penchant for native cutthroat. After dropping off clients he’d hustle back out to scout for the next trip. He scouted until dark and sometimes after, kneeling in willows by the river and waiting for a trout to rise. He came home stinking of fish gut and woke her with his eager stories, cutthroat trout leaping fifteen-foot cataracts, a stubborn rainbow wedged under a snag.

By June she was bored and lonely. She wandered through the woods, but never very far. The summer woods were dense and busy, nothing like the quiet graveyard feel of winter. You couldn’t see twenty feet in the summer. Nothing slept for very long; everything was emerging from cocoons, winging about, buzzing, multiplying, having litters, gaining weight. Bear cubs splashed in the river. Chicks screamed for worms. She longed for the stillness of winter, the long slumber, the bare sky, the bone-on-bone sound of bull elk knocking their antlers against trees. In August she went to the river to watch her husband cast flies with a client, the loops lifting from his rod like a spell cast over the water. He taught her to clean fish in the river so the scent wouldn’t linger. She made the belly cuts, watched the viscera unloop in the current, the final, ecstatic visions of trout fading slowly up her wrists, running out into the river.

In September the big-game hunters came. Each client wanted something different: elk, antelope, a bull moose, a doe. They wanted to see grizzlies, track a wolverine, even shoot sandhill cranes. They wanted the heads of seven-by-seven royal bulls for their dens. Every few days he came home smelling of blood, with stories of stupid clients, of the Texan who sat, wheezing, too out of shape to get to the top of a hill for his shot. A bloodthirsty New Yorker claimed only to want to photograph black bears, then pulled a pistol from his boot and fired wildly at two cubs and their mother. Nightly she scrubbed blood out of the hunter’s coveralls, watched it fade from rust to red to rose in the river water.

He was gone seven days a week, all day, home long enough only to grind sausage or cut roasts, clean his rifle, scrub out his meat pack, answer the phone. She understood very little of what he did, only that he loved the valley and needed to move in it, to watch the ravens and kingfishers and herons, the coyotes and bobcats, to hunt nearly everything else. There is no order in that world, he told her once, waving vaguely toward Great Falls, the cities that lay to the south. But here there is. Here I can see things I’d never see down there, things most folks are blind to. With no great reach of imagination she could see him fifty years hence, still lacing his boots, still gathering his rifle, all the world to see and him dying happy having seen only this valley.

She began to sleep, taking long afternoon naps, three hours or more. Sleep, she learned, was a skill like any other, like getting sawed in half and reassembled, or like divining visions from a dead robin. She taught herself to sleep despite heat, despite noise. Insects flung themselves at the screens, hornets sped down the chimney, the sun angled hot and urgent through the southern windows; still she slept. When he came home each autumn night, exhausted, forearms stained with blood, she was hours into sleep. Outside, the wind was already stripping leaves from the cottonwoods—too soon, he thought. He’d lie down and take her sleeping hand. Both of them lived in the grips of forces they had no control over—the November wind, the revolutions of the earth.

That winter was the worst he could remember: from Thanksgiving on they were snowed into the valley, the truck buried under six-foot drifts. The phone line went down in December and stayed down until April. January began with a chinook followed by a terrible freeze. The next morning a three-inch crust of ice covered the snow. On the ranches to the south cattle crashed through and bled to death kicking their way out. Deer punched through with their tiny hooves and suffocated in the deep snow beneath. Trails of blood veined the hills.

In the mornings he’d find coyote tracks written in the snow around the door to the crawlspace, two inches of hardwood between them and all his winter hoard hanging frozen now beneath the floorboards. He reinforced the door with baking sheets, nailing them up against the wood and over the hinges. Twice he woke to the sound of claws scrabbling against the metal, and charged outside to shout the coyotes away.

Everywhere he looked something was dying ungracefully, sinking in a drift, an elk keeling over, an emaciated doe clattering onto ice like a drunken skeleton. The radio reported huge cattle losses on the southern ranches. Each night he dreamt of wolves, of running with them, soaring over fences and tearing into the steaming, snow-matted bodies of cattle.

Still the snow fell. In February he woke three times to coyotes under the cabin, and the third time mere shouting could not send them running; he grabbed his bow and knife and dashed out into the snow barefoot, already his feet going numb. This time they had gone in under the door, chewing and digging the frozen earth under the foundation. He unbolted what was left of the door and swung it free.

A coyote hacked as it choked on something. Others shifted and panted. Maybe there were ten. Elk arrows were all he had, aluminum shafts tipped with broadheads. He squatted in the dark entryway—their only exit—with his bow at full draw and an arrow nocked. Above him he could hear his wife’s feet pad silently over the floorboards. A coyote made a coughing sound. He began to fire arrows steadily into the dark. He heard some bite into the foundation blocks at the back of the crawlspace, others sink into flesh. He spent his whole quiver: a dozen arrows. The yelps of speared coyote went up. A few charged him, and he lashed at them with his knife. He felt teeth go to the bone of his arm, felt hot breath on his cheeks. He lashed with his knife at ribs, tails, skulls. His muscles screamed. The coyote were in a frenzy. Blood bloomed from his wrist, his thigh.