Читать книгу The World of Sicilian Wine - Bill Nesto - Страница 12

Оглавление1

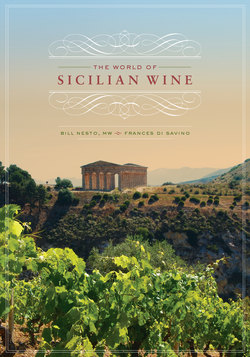

THE ORIGINS OF SICILIAN WINE AND CULTURE

The culture of wine in Sicily is both ancient and modern. There is evidence of vine training and wine production from the earliest settlements of the Phoenicians on Sicily's west coast and the Greeks on Sicily's east coast from the eighth century B.C. In the long parade of foreign powers and people who have invaded and settled Sicily, it was the Greeks who brought an established culture of wine to this island. For the Greek settlers from mainland Greece and its islands, Sicily was the fertile and wild frontier on the western edge of their Mediterranean world. The gods and heroes of Greek mythology also ventured to Sicily. Upon sailing to Sicily, the protagonist-hero of Homer's Odyssey, Odysseus, together with his crew of men, approached the mighty Mount Etna and the untamed land of the Cyclops with more than a little trepidation. The Cyclops are the giant one-eyed creatures who in ancient mythology dwelled on Mount Etna (and who were reputed to eat wayward explorers). Homer gives us the following account of this forbidding race:

At last our ships approached the Cyclops’ coast.

That race is arrogant: they have no laws;

and trusting in the never-dying gods,

their hands plant nothing and they ply no plows.

The Cyclops do not need to sow their seeds;

for them all things, untouched, spring up: from wheat

to barley and to vines that yield fine wine.

The rain Zeus sends attends to all their crops.

Nor do they meet in council, those Cyclops,

nor hand down laws; they live on mountaintops,

in deep caves; each one rules his wife and children,

and every family ignores its neighbors.1

From these twelve lines, probably written around the time of the earliest Greek settlements in eastern Sicily, Homer tells us much about the image and reputation of Sicily among his fellow Greeks since Odysseus's mythical time during the Mycenaean Age, between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries B.C. He describes the island as a lawless but wildly fertile place. The natives are beasts who lack any farming skills or tools. The Sicilians, according to Homer, lack culture (i.e., the essential skills to cultivate soil). And yet the wheat, the barley, and the “vines that yield fine wine” thrive all the same. We also learn that the indigenous people are an insular patriarchal tribe who ignore even their own neighbors. Homer then adds that such creatures are neither explorers nor artisans but inhabit a generous land which a little industry could make an island of plenty.

The Cyclops have no ships with crimson bows,

no shipwrights who might fashion sturdy hulls

that answer to the call, that sail across

to other peoples’ towns that men might want

to visit. And such artisans might well

have built a proper place for men to settle.

In fact, the land's not poor; it could yield fruit

in season; soft, well-watered meadows lie

along the gray sea's shores; unfailing vines

could flourish; it has level land for plowing,

and every season would provide fat harvests

because the undersoil is black indeed.2

What is so striking about this description is how little the outsider's image of Sicily and Sicilians has changed in the intervening 2,700 years. Many of the cultural shortcomings and natural qualities that Homer chronicles are writ large throughout much of Sicily's history, for reasons that this chapter will explore. That may make Homer as much an epic prophet as an epic poet. The history and culture of Sicily, however, are far richer and more complex than any literary representation of them. Sicily has been defined and dominated by outsiders since its earliest time. Odysseus and his fellow Greeks were among the first. They would be followed in turn by Romans, Vandals, Goths, Byzantines, Muslims, Normans, Germans, French, Spanish, Austrians, and Northern Italians. Sicily's fertile land, sun-filled climate, and strategic position in the Mediterranean made the island enticing plunder for the pillaging forces of these various outside powers. And yet the Sicilians themselves have played a central role in their land's history of glory, subjugation, violence, and unrealized promise. In the thirteenth-century world map known as the Ebstorf Mappamundi (which was the largest on record prior to its destruction by Allied bombing over Hanover, Germany, in World War II), the island of Sicily was portrayed as a plump heart-shaped apple or pomegranate smack in the center of the area between Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Sebastian Münster's sixteenth-century book of world geography, known as the Cosmographia, depicts Sicily as the cross-bejeweled orb (the symbol of Christian temporal power) in the right hand of the “Queen Europe” map. But by the end of the twentieth century, Sicily would sadly have no place in the popular cultural landscape beyond Corleone, the Mafia town made famous by The Godfather. For the modern wine lover, however, the search for Sicilian terroir demands an understanding of place beyond the conventional historical and cultural narratives.

GREEK ROOTS AND SHOOTS

Before the Greeks and the Phoenicians reached the shores of Sicily, there were at least two groups of “indigenous” peoples, the Sicans on the western side and the Sicels on the eastern side. The Sicans are thought to have come from the Iberian Peninsula and the Sicels from Calabria (the toe of Italy). There were also settlements in northwestern Sicily near modern-day Erice, Segesta, and Contessa Entellina of a people called the Elymians, believed to have migrated from ancient Troy (in modern-day Turkey). While documented archaeological evidence does not substantiate that these early settlers trained vines or made wine, there is botanical evidence of wild grapes during this prehistoric period. There is also speculation that the Mycenaean Greeks, who had an established culture of wine by the thirteenth century B.C., introduced wine and other luxury products to Sicily well before the earliest Greek colonies settled there in the eighth century B.C.3

In an oft-quoted passage in the same book of the Odyssey that introduces us to the Cyclops, Homer offers a critique of the quality of Sicilian wine in comparison with the strong, full-bodied Maronean wine from the southern Balkan region (known as Thrace in his time) that Odysseus carried on board his ship. After Odysseus offers a taste of his wine to the Cyclops named Polyphemus, the native beast declares:

Surely the earth, giver of grain, provides

the Cyclops with fine wine, and rain from Zeus

does swell our clustered vines. But this is better—

a wine as fragrant as ambrosia and nectar.4

According to Homer, a natural Sicilian wine made from wild grapes was no match for Greece's finest wines. To the modern reader, this might sound like the chauvinism of a connoisseur of Old World wines assessing the wines of the New World. However, it is well established that the Greek colonists brought their cultivated knowledge of vine training and winemaking to southern Italy and Sicily beginning with their earliest settlements. It is also believed that the Greeks brought distinct vine varieties from the Aegean to Sicily. Homer describes the vineyard of Odysseus's father, King Laertes, on the Greek island of Ithaca as having “some fifty rows of vines, each bearing different grapes—so many kinds—that ripened, each in turn and in its time.”5 As a testament to the influence of the Greek settlers on Italian viticulture, the ancient Greeks referred to southern Italy and Sicily as Oenotria ("The Land of Trained Vines").6 In the wooded hills above the town of Sambuca in southwestern Sicily, a young winegrower by the name of Davide Di Prima brought us to a clearing in a forest on a high plateau to see a stone pigiatoia ("outdoor winepress") from the fifth century B.C. These ruins are believed to be a place where a Sican settlement crushed and vinified grapes. While the age of this site does not predate Phoenician or Greek settlement on the island, it does point to an indigenous culture of wine that coexisted with such settlements.

Greek settlers in Sicily brought other vital elements of their wine culture to their new home. Archaeologists have discovered that the earliest Greek settlers traded ceramic wine wares with the Sicel native population in the coastal areas of eastern Sicily, including amphorae, large bowls, and other wine-drinking vessels. Archaeologists discovered a small pouring vessel from the fifth century B.C. called an askos near the central Sicilian town of Enna. It is inscribed with the word vino, among the earliest documented uses of this word prior to its introduction into the Latin language. One object that has not been identified in Sicel archaeological sites is the krater, or mixing bowl, which Greeks used to mix their wine with water in varying proportions depending on the occasion. This leaves open the question of whether the Sicels (like the Cyclops) drank their wine undiluted. Regardless, the evidence of this trading pattern demonstrates an immediate interest by the local Sicels in the consumption and culture of wine. Anthropologists call this process acculturation. This acculturation would have necessarily involved other elements of the Greek wine culture, such as the ritual of the symposium (which literally means “drinking together” in Greek). The Greek symposium was an extended after-dinner wine-drinking celebration (men only) that often involved the recitation of poetry, the playing of music, dancing, and other earthly pleasures. Archaeologists theorize that wealthier Sicels adopted certain elements of the symposium into their own cultural traditions. With the eventual intermarriage of the Greek colonists and the native Sicels, the assimilated Greek Sicilians added a new activity to their wine parties: the drinking game of kottabos. Kottabos was played toward the end of the party, when celebrants had emptied their cups and spirits ran high. The aim of the game was for each player to fling the remaining wine drops and sediment in his cup toward a suspended disc or other target to bring it crashing to the ground. The game became associated with Sicily, and its popularity spread to Greece as a fashionable staple of the Athenian symposium.

Beginning in the sixth century B.C., Greek Sicilian poets, playwrights, and philosophers were honored in the classical Greek world. The stature of such cultural figures in Greece suggests that literary exchanges were an integral part of the Greek Sicilian symposium. The Greek word symposium also refers to a category of literature regarding food and wine. Epicharmus, the Sicilian playwright and philosopher from the late sixth and early fifth centuries B.C. (who was also a student of Pythagoras), is considered the father of the Greek comic play. The Greek word for comedy derives from comus, "wine lees,” and literally translates as “lees song.” In ancient Greece, drunken, rowdy processions in honor of the Greek god of wine, Dionysos, accompanied the harvest festivals. Epicharmus was the first playwright to introduce the drunkard as a stock comic character. The remaining fragments of his plays are also replete with references to the culinary delights of his fellow Greek Sicilians in the city of Syracuse.7 Epicharmus preached moderation and perhaps was using the vehicle of comedy to caution his fellow Greek Sicilians on the pitfalls of excess wine and food consumption. One of the many moral maxims attributed to him exhorts: “Be sober in thought! Be slow in belief! These are the sinews of wisdom.”8

The Sicilian-born poet Theocritus, who is credited with creating the genre of bucolic poetry in the third century B.C., celebrated the beauty of the Sicilian countryside and the joy of country life. In one of his idylls, Polyphemus (the milk-guzzling Cyclops of Homer's Odyssey) is a fellow Sicilian countryman who sings a love poem about the natural glory of Mount Etna, including the “sweet-fruited vine.”9 From Theocritus we learn that Greek Sicilians even savored aged wine. In the idyll called “The Harvest Home” the poet refers to a four-year-old vintage opened for a harvest feast.

Darted golden bees; all things smelt richly of Summer,

Richly of Autumn; pears and apples in bountiful plenty

Rolled at our feet and sides, and down on the meadow around us

Plum-trees bent their trailing boughs thick-laden with damsons.

Then from the wine-jar's mouth was a four-year-old seal loosened.10

Sicily by this time was widely regarded as the gastronomic epicenter of the classical Mediterranean world. Sicilian chefs were renowned in ancient Greece as the Ferran Adriàs and Thomas Kellers of their day. Sicilian raw ingredients, including cheese and tuna, were also prized as luxuries on the Greek table. Archestratus, a Greek Sicilian of the fourth century B.C., wrote a detailed poem titled “Gastronomy,” “Art of Cooking,” or “Life of Luxury” depending on the translation. In it, he describes and ranks the food and wine of the entire Mediterranean basin. Like Theocritus, he confirms that “gray-haired” wine is for special occasions.11 Like our modern wine journalists, he also assesses the relative merits of wines from various places. In one passage, the author compares the wines from the Greek island of Lesbos with the Bibline wine from Phoenicia, concluding that the Bibline wine is more aromatic than the Lesbian wine but inferior on the palate. Archestratus boasts that unlike other writers of his day, who just “like to praise what they have in their own land,” he is able to critique wines from everywhere.12

In chronicling the distinctions among various wines and foods throughout the Mediterranean, the poetic works of Archestratus and the Greek Sicilian Philoxenus provide ample evidence that Sicilians by the fifth century B.C. understood and appreciated the concept of place and its impact on flavor and quality. What was essential to this understanding and appreciation was the flow of people and goods between the Greek settlements in Sicily and the Greek mother cities (metropolises). Sicilian athletes regularly went to Greece to compete in the Olympics, and Sicilian cooks traveled through Greece as celebrity chefs on tour. In this same period the Greek city now known as Agrigento, on the southern coast of Sicily, built its magnificent temples with the wealth derived in no small measure from the exporting of wine and olive oil to North Africa. In time, merchants from other Sicilian city-states also entered the export wine trade and began to compete successfully with Greek wine merchants throughout the Mediterranean and as far north as Gaul in modern-day France. In the third century B.C. the ruling tyrant of Syracuse, Hiero II, commissioned the construction of a massive “garden ship” named The Syracusan. The top deck was carpeted with flower beds and an arbor of ivy and vines. Capable of carrying more than three thousand tons of crops and other cargo, the ship was renowned for both its opulence and its tonnage. Like Agrigento, the celebrated city-state Syracuse built its wealth on the production and export of abundant grain, olives, and wine. Hiero II himself controlled vast agricultural holdings and even wrote a handbook on agronomy. Both the poets and the merchants of the classical Greek world recognized the quality of Sicilian wine and food. The era of Sicily as a wine-producing and wine-exporting region had arrived.

ROMAN BREAD AND WINE

By the beginning of the second century B.C., Sicily was firmly under the control of Rome and would be relegated to serving as the granary of the Roman Empire for almost six hundred years. The fertility of Sicily, which had made it the land of plenty for Greek settlers and their vines beginning in the eighth century B.C., also made it the bread basket for the Romans and the succeeding foreign powers that came to control and exploit the island. In the mythology of ancient Rome, Ceres, the goddess of agriculture and grain, made her home in Sicily and as the creator of the art of husbandry was considered the first giver of laws to mankind. Unlike the cultivation of wine grapes and olives, which required intensive skill-based farming and harvesting, the growing of grain was more efficiently accomplished on large expanses of land. These vast farms, known as latifundia, were managed by wealthy absentee landowners (both Roman and Sicilian) and worked by local or imported unskilled slave or peasant labor. Following the end of the Roman era many of these latifundia were in the hands of the Catholic Church and increasingly a growing class of landed “nobility.” During Roman rule the absentee landowner, as would be the case with ecclesiastical and noble landowners in subsequent epochs, would lease out significant holdings of land to an intermediate “tenant-in-chief,” who in turn would wield enormous control over the peasant tenant farmers who worked the land. This pattern would ultimately become the foundation for the feudal economy that suffocated Sicily into the nineteenth century.

The extent of Sicily's wine production and wine exports during the period of Roman rule is not precisely known. However, there is historical evidence that several Sicilian wines were known and prized on the Roman table. Amphorae have been discovered in the ruins of Pompeii (itself a celebrated wine zone in ancient Rome) bearing the inscription “Mesopotamium,” the Latin name of a wine from the southeast coast of Sicily. In his treatise from the late first century B.C. and early first century A.D., the Greek geographer Strabo states that the district around Messina “abounds in wine” called Mamertinian, which “vies with the best produced in Italy.”13 Strabo also gives us a description of the volcanic terroir of Mount Etna that could come right out of a modern wine book: “However, after the burning ashes have occasioned a temporary damage, they fertilize the country for future seasons, and render the soil good for the vine and very strong for other produce, the neighboring districts not being equally adapted to the produce of wine.”14

The Latin agricultural treatises of the Roman writers Pliny (Natural History) and Columella (On Agriculture) of the first century A.D. and the Greek literary work known as The Learned Banqueters by Athenaeus of Egypt in the second century A.D. include several specific references to the esteemed wines and foods of Sicily. Columella also praises the written contributions of learned Sicilians to the science of husbandry.15 Pliny cites the Hybla region of Sicily as producing some of the finest-quality honey, being that it is “obtained from the calyx of the best flowers” and ferments in its first few days “like new wine.”16

The notable Sicilian wines that Pliny, Columella, and Athenaeus catalogue include the esteemed Mamertine wine from near Messina that was named Potitian after its original grower and was an early example of “ ‘château-labelling’ of a good growth.”17 In reference to the Eugenia vine variety, which was transported from Sicily to the Alban Hills southeast of Rome (the equivalent of a Roman grand cru), Pliny wrote that “with its name denoting high quality” it was “imported from the hills of Taormina to be grown only in the territory of Alba, as if transplanted elsewhere it at once degenerates: for in fact some vines have so strong an affection for certain localities that they leave all their reputation behind there and cannot be transplanted elsewhere in their full vigour.”18 Pliny's statement provides ample proof that the idea of terroir is indeed ancient.

Two other Roman vine varieties believed to be of Sicilian origin were Murgentina and Aminnia. Murgentina was exported from Sicily to the region of Mount Vesuvius and was the principal variety in a wine aptly called Pompeiana or Vesuvinum. Aminnia, on the other hand, was part of a group of vine varieties identified with both the Italian mainland and Sicily and was the only varietal wine classified among the most permissibly expensive by edict of the Roman emperor Diocletian at the end of the third century A.D.19 The migration of vine varieties and viticultural knowledge from Sicily to Rome evolved out of the original migration of Greek viticulture to Sicily beginning with the earliest Greek settlements in the eighth century B.C.

The founding legend of Rome is based on the story of a mythical hero, Aeneas, who spends formative time in Sicily on his epic voyage from Troy to central Italy. The Roman poet Virgil, writing in the first century B.C., recounts the adventures of Aeneas in the epic Latin poem the Aeneid. Like the Odyssey, the Aeneid takes place after the legendary conquest of Troy by the Mycenaean Greeks, believed to be sometime between 1300 and 1100 B.C. Aeneas, the last surviving prince of Troy following its defeat by the Greeks, is compelled to reach the shores of Italy in order to fulfill a divine prophecy that he will found Rome. On their voyage to the Italian mainland, he and his countrymen travel by ship around the Sicilian coast and land in northwestern Sicily. King Acestes, who is also of Trojan lineage and who founded the Elymian cities of Eryx, Segesta, and Entella, gives Aeneas a gift of Sicilian wine before Aeneas sets sail for Italy. After Aeneas and his men have shipwrecked on the shores of Carthage and the men have all but given up any hope of ever reaching their longed-for new home in Italy, Aeneas

. . . shares

the wine that had been stowed by kind Acestes

in casks along the shores of Sicily:

the wine that, like a hero, the Sicilian

had given to the Trojans when they left.20

Aeneas “soothes [the] melancholy hearts” of his men with the wine gifted by the heroic Sicilian king.21 Unlike in the Odyssey, where it is the Greek hero who offers ambrosial wine to the brutish Sicilian Cyclops, in the Aeneid it is the gracious Sicilian king who gives the precious gift of wine and solace to the Trojan hero. Virgil, who was writing seven centuries after Homer, would have been well aware of the influence of Greek culture and viticulture in Sicily. The founding legend of Rome, however, envisioned a Sicily whose culture was built by its mythological ancestors, the last surviving Trojan kings and princes, not by the Greeks. In reality, Sicily—apart from tourist attractions like Mount Etna and the ancient ruins of Syracuse and Agrigento—did not have a high profile in the official annals of the Roman era. Its utility was based principally on the quality and reliability of its production of summer wheat, a commodity. In purely mythological terms, however, Sicily and Sicilian wine played a seminal role in the epic narrative of Roman history as told in Virgil's Aeneid.

MUSLIMS AND NORMANS BEAR FRUIT

After the fall of the Roman Empire, first Vandals and then Goths, two different Germanic tribes, overran Sicily. Beginning in the sixth century A.D. the emperors from Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), the capital city of the Eastern Christian Empire, took control of Sicily. Then, in the first quarter of the ninth century, a sizable army of Arabs, Berbers from North Africa, and Spanish Muslims began to invade Sicily. As for previous conquerors, Sicily's strategic position in the Mediterranean and its lush fertility were powerful draws for the Muslim invaders. It would take approximately seventy-five years for the Muslims (referred to by medieval chroniclers as Saracens) to complete their conquest of the island and to supplant Sicily's Greek culture with a Muslim one (except in the northeastern part of the island known as Val Demone, which remained predominantly Greek).

The period of Muslim control lasted almost two hundred years (878–1061) and ushered in a golden age for Sicilian agriculture. Based on the system of Islamic fiscal administration in the Muslim strongholds of Libya and Tunisia, the Muslims in Sicily imposed a fixed-rate annual land tax (called the qānūn or kharāj) that landowners had to pay regardless of their crop yield.22 This incentivized the productive use of cultivatable land. (By contrast, with certain limited exceptions, the baronial class in Sicily following the decline of the Normans would jealously resist any taxation based on their agricultural landholdings until the middle of the nineteenth century, even when their foreign sovereigns urged them to undertake such tax reform.) The Muslim rulers used a portion of the revenue from land taxes to make land grants of small farms to soldiers, creating a broad base of free landholders. The Muslim laws of inheritance led to the further fragmentation of farms among families over generations, thus providing an additional incentive for the efficient and intensive cultivation of land by the heirs of ever-smaller parcels. These smaller landholdings, while not supplanting the latifundia established in the Roman era, were concentrated in hamlets around the island (particularly around the cities) and provided peasant farmers with the opportunity to own and work their own land. The Muslims also provided exemptions from the land tax to certain classes of disadvantaged landowners—such as widows and the blind—as well as young married couples and immigrants for a period of time, as a direct incentive to “establish their new household and their new lands.”23

With an advanced knowledge of irrigation and intensive farming, the Muslims created a polyculture of small farms, orchards, and gardens principally in the western and southeastern areas of the island. They cultivated a variety of new food plants and other crops in Sicily, including hard durum wheat. Beginning in the Muslim era, the market gardens of Palermo brimmed with lemons, bitter oranges, melons, apples, pomegranates, pears, peaches, grapes, quinces, mulberries, eggplant, saffron, date palms, dried figs, sugarcane, apricots, bananas, mangoes, sesame seeds, pistachios, hazelnuts, and almonds.

During this period, however, there was less emphasis on the cultivation of wine grapes than during the Greek and even Roman eras. Still, although Muslim law prohibits the drinking of wine in public, it is unlikely that the cultivation of wine grapes and the production of wine ceased in Sicily (any more than it did in Prohibition-era United States). The Muslim Sicilian poetry of the twelfth century is replete with references to wine and the pleasures of wine drinking. While such poetry is consistent with a Muslim genre that uses the image of wine metaphorically, it also reveals an intimate familiarity with an established wine culture in Sicily. In one of his odes recalling the idyllic pleasure of his youth in Sicily prior to the Norman conquest, the Muslim poet Ibn Hamdis describes in familiar detail the qualifications of a wine expert:

A youth who has studied wine until he knows

the prime of the wines, and their vintage

He counts for any kind of wine you wish

its age, and he knows the wine merchant24

In the lines of another Arabic poem, written by an anonymous poet believed to be an emir in Palermo during the period of Muslim rule, the imagery of the garden paradise is intricately woven with the recollections of a self-avowed wine lover who savors “a well-matured wine, more exquisite than youth itself.”25

Notwithstanding the nostalgic image of Sicily as a garden paradise in Muslim Sicilian poetry, internal strife among the various Muslim factions controlling the island ultimately created ripe conditions for its conquest by the Normans in the second half of the eleventh century. The first Norman ruler, Count Roger, came from northwest France and was of Viking lineage. The unique legacy of the Norman line of kings, beginning with Count Roger's son, King Roger II, was the degree to which these foreign rulers established centralized authority in Sicily and incorporated a professional class of Greek and Muslim Sicilians into their administrative, military, and court regimes. For the first and only time, an all-powerful and resident sovereign ruled the island, directly enforcing the rule of law, the payment of taxes, and the administration of justice—for baron, landowner, and peasant alike. The early Norman rulers even established almost complete control over ecclesiastical matters.

During the initial period of their rule, the Norman kings maintained the Muslim pattern of existing small farms while carving out the majority of the island as bigger landholdings for themselves and a tight group of fellow mercenaries-cum-barons. Many of the land grants that the early Norman rulers made to the new barons did not, however, convey rights of inheritance. In addition, because the Norman rulers employed a professional army and navy (using Muslim troops and expertise), they were not as dependent as their feudal counterparts in northern Europe on their baronage. As a result, the new Sicilian baronial class was politically weak. The Norman kings set and steered the economic, political, military, judicial, and cultural course of Sicily from their palace courts in Palermo. The court of Roger II and his successors was a dazzling synthesis of Latin, Greek, and Muslim traditions and influences. As under Muslim rule, Sicilian agriculture and commerce thrived under the efficient governance of the Norman kings. Small farmers continued the intensive cultivation of fruit trees and vines along with grain. The Book of Roger, written in the twelfth century by King Roger II's Muslim court geographer, al-Idrisi, describes Sicily as a garden paradise where exquisite fruit and other cultivated crops abound. It also celebrates the presence of perennial water and identifies grapevines as being well adapted to certain locations, such as Caronia on Sicily's north coast and Paternò on Mount Etna.

The wealth of the Norman kingdom of Sicily under Roger II was astounding. By one account, his revenue from the city of Palermo was greater than that of the first Norman king of England, William the Conqueror, from the entire country of England. Another account tells of the retinue of ships sailing from Sicily with King Roger II's mother, Adelaide, on her way to become the queen of Jerusalem, laden with “wheat, wine, oil, salted meats, arms, horses and, not least, an infinite amount of money.”26 Under Norman rule Palermo was esteemed as one of the great cities of the civilized world, along with Cordoba, Cairo, and Baghdad. Shipwrecked on the eastern coast of Sicily on his return from Mecca, a Muslim scholar named Ibn Jubayr chronicled his travels across the island on his way home to the royal court of Granada. He had left Spain on a pilgrimage to Mecca as penitence for having been pressured into drinking a cup of wine. His chronicles alternate condemnation of the ruling Norman infidels with praise for the richness of Sicily and its rulers. On the final leg of his voyage to the port of Trapani on Sicily's western coast to board a ship bound for Spain, Ibn Jubayr recounted how the fertility of the Sicilian soil, both tilled and sown, was unlike any he had seen before and surpassed even the choiceness of Cordoba's countryside.27 As further testament to the prosperous and vibrant culture of Norman Sicily, a Norman chronicler writing under the name Hugo Falcandus described Palermo as a luxuriant garden under the last king of pure Norman origin, William II.28 While his language is consistent with the rhetorical flourishes of a public eulogy for a royal patron, the image and detail cannot be ignored for what they reveal about Sicily's agricultural wealth under Norman rule.

In addition to its creation of magnificent palaces, churches, and parks, the period of Norman rule was exceptional for its protection of Sicily's islandwide natural resources: water, plains, woodland, and marshes. The Norman rulers also assumed responsibility for maintaining the kingdom's roads. The continued vibrancy of Sicilian agriculture during the Norman era must have been served well by the safeguarding of the public's interest in these vital resources. The common good was served not just by the Norman kings and their feudal nobles but by the boni homines ("good men") of the local countryside, who honored their civic responsibilities to defend public property (res publica).

Alas, there was trouble in paradise. By the middle of the twelfth century a growing and restive baronial class was pushing for greater political power and autonomy. Unlike the city-states of Tuscany and northern Italy, Sicily's Palermo, Messina, and Catania had no independent urban merchant class to balance the power of the landowning baronage. The synthesis of Latin, Greek, and Muslim cultures in the courts and palaces of the Norman rulers also never reflected a true integration among the cultures throughout the island. The building tensions between Christians and Muslims ultimately erupted in open violent conflict. Muslims escaped to the interior of the island or were exiled to other parts of the Mediterranean. The loss of Muslim farmers and culture fundamentally eroded the splendid quality and diversity of Sicilian agriculture. Upon the death of the last Norman Sicilian king, William II, the chronicler Hugo Falcandus grasped what was at stake for Sicily and prophetically asked what his fellow Sicilians were prepared to sacrifice to maintain their freedom and prosperity: “What plan do you believe the Sicilians will pursue? Will they believe that they must name a king and fight against the barbarians with united forces? Or rather with diffidence and a hatred of unaccustomed labor make them slaves of circumstance: Will they prefer to accept the yoke of a prodigiously difficult slavery, rather than defend their reputation and their dignity and the liberty of their land?"29

This would tragically remain Sicily's unanswered challenge. The Norman kings were succeeded by a line of German (Swabian) kings, who inherited the mantle of Norman rule through Henry VI's marriage to Constance, the daughter of King Roger II. Although the succession of these German kings, culminating with King Frederick II in the first half of the thirteenth century, would in many ways extend the prosperity enjoyed by Sicily under their Norman predecessors, Sicily following their reign would never again be an independent or self-sufficient state. It would once again, as under Roman rule, become a granary of continental European empires. In the end, both distant kings and local barons would exploit Sicily's cherished fertility.

WINE-DARK AGES

The last king in the Swabian line died in the middle of the thirteenth century, and during the next five centuries Sicily became an increasingly impoverished and backward corner of western Europe. The island was treated as geopolitical chattel by the French, Spanish, Piedmontese, Austrians, and Bourbons before becoming unified with the Italian mainland in the middle of the nineteenth century. Instead of a heart-shaped apple or pomegranate, Sicily would have been more accurately depicted in a map during this period as a soccer ball kicked around by the power players of continental Europe. The easy historical narrative dwells on this external reality and hardship. And while Sicily's prolonged subjugation to foreign powers undoubtedly was a root cause of its people's poverty and ignorance, this was not the only cause. As the Norman kingdom disintegrated, the noble class in Sicily grew in size and wealth. Beginning with the first waves of Norman and German mercenaries who ventured to Sicily to fight for and support their new sovereigns and who were awarded with land grants and noble titles, the island's baronage consisted largely of the second (and third and fourth) sons of continental Europe, who came to Sicily to make their fortunes and buy their stripes. This was neither an indigenous upper class nor a noble class with shared values and a common purpose. In contrast with the Florentine Republic (a Tuscan city-state dating from the early twelfth century), which began to emerge from the Middle Ages by the end of the thirteenth century, Sicily declined into its own “dark ages” at that time. The Renaissance never flowered in Sicily. And while vines were widely planted and wine was continuously made for local (and even foreign) consumption by Sicilians during the following centuries, the science, art, and business of viticulture and vinification languished in Sicily. If a true culture of wine represents the most cultivated expression of agriculture, then it can be fairly stated that the five centuries following the fall of the last Swabian kings were Sicily's “wine-dark ages” in terms of its agricultural evolution.30

With certain notable exceptions, the Sicilian barons fought to preserve their rights and privileges as feudal lords over their ever-expanding lands, including the powers of taxation and justice, without honoring their historical duties of military service or protection of the public good on behalf of their sovereign. The Sicilian baronage succeeded in preserving the benefits while burying the responsibilities of feudalism. This was a perverted form of feudalism, with deep roots and a rotten core. The foreign sovereigns of Sicily, for their part, were prepared to give the Sicilian barons almost complete local control over their feudal lands in exchange for their subservience. Owning property in Palermo exempted nobles from the taxation of their latifundia in the countryside. Although the Sicilian nobles controlled only one of the three houses in the Parliament based in Palermo, they almost fully controlled the apportionment and collection of taxes to be paid to their foreign rulers. Rather than assuming the payment of taxes based on their vast landholdings, the nobles pushed taxation down to the level of the peasants who worked their lands. Beginning in the sixteenth century, a regressive tax called the macinato was implemented, taxing the milling of grain by tenant farmers. The large landowning barons compelled their tenant farmers to pay multiple additional taxes—for the protection of the baron's property on which they toiled, the right to press olives and grapes in the baron's press, the right to hunt on the baron's land, the right to use the baron's poultry yard, and even the right to attend Mass in the baron's private church. As late as the end of the eighteenth century, some baronial landowners compelled their tenant farmers to pay such taxes by forcing them to grind their grain at the barons’ mills and to crush their olives and grapes in the barons’ presses.31 A baron exercising his ancient rights as a feudal lord could even impose a marriage tax as a condition of granting permission for his tenant farmers’ daughters to marry. In effect, these latifondisti created a private system of taxation to squeeze (in Italian, sfruttare) as much as possible from their tenant farmers.

Sicily's polyculture from the Muslim and Norman eras devolved over the succeeding centuries largely into a monoculture of grain: hard durum wheat. Barons extended their power and prestige by acquiring greater tracts of lands. They used the revenue from their holdings not to improve the quality of agriculture on their lands but rather to acquire more lands and to establish new town settlements under their sole legal, fiscal, and judicial jurisdiction. Such wealth also funded the opulent urban lifestyles to which this noble class had become deeply attached. The nobles commonly became absentee landlords who shunned the active management of their lands and in many cases were ignorant of the boundaries of these lands.

In stark contrast with the Norman era, when there was a strong central authority based in Palermo and the unwavering rule of law islandwide, in the five centuries from the end of the thirteenth century until the end of the eighteenth century, there was not one set of laws or one ruler to enforce them in Sicily. The island had one set of laws and courts for clergymen and different legal systems and forums for nobles, merchants, and peasants. The debts and taxes of nobles remained unpaid at the same time that the same nobles hired brigands and gangs to enforce (with the emphasis on force) the subjugation of their sharecropper tenants to the “law” of their lands. As the nobles expanded their landholdings, they hired former field workers and local strongmen to aggressively manage their lands in a form of tenancy called gabella. The gabella usually involved a three-to-six-year lease on the whole estate and required the manager, known as the gabelloto, to pay his rent up front. The gabelloti in turn became the tyrannical enforcers of their overlords’ lands, collecting rents and taxes and meting out “justice” to the peasant sharecroppers. The sharecroppers were subject to short-term leases, which gave them no security of tenure on the land and thus no incentive to invest in capital- or labor-intensive arboriculture such as vines or olive, nut, or fruit trees. Short-term leases also resulted in severe overcropping and the destruction of precious woodland to create more pasturage and farmland. The sharecropper farmers (and itinerant day laborers) had only the most primitive tools and often had to travel hours each day to work the land. In the end, the short-term interests of the nobles and their gabelloti led to severe long-term problems of soil erosion, landslides, and the disappearance of rivers and streams. The export market for Sicily's durable hard wheat was also dwindling, given its high costs of production and the emergence of ships that could more quickly transport northern Europe's less-durable summer wheat to market.

Given the difficulty of collecting taxes from the nobles, Sicily's foreign rulers resorted to other revenue-raising measures. They sold all manner of noble titles and privileges. In the seventeenth century alone, the Spanish king granted 102 new princedoms in Sicily.32 The competition in the baronial class for social rank and prestige was astounding, even by the standards of the foreign sovereigns and their emissaries.33 The Sicilian nobles, by and large, were not educated or even literate. They poured their agricultural revenue into ornate palaces and grandiose lifestyles in Palermo, Messina, and Catania. Many spent themselves into poverty and became borrowers from their gabelloti underlords. The gabelloti, as the new so-called buon signori ("good men") or galantuomini ("honorable men") of the countryside, then aspired to noble titles and palaces themselves. Unlike the boni homines of the Norman era, they—and their noble bosses—were unconcerned with the res publica. In marked contrast with the power of the urban mercantile class in the Tuscan and northern Italian city-states, Sicily's cities had no robust intellectual, merchant, or artisan class to check the power of the bulging noble class. These urban classes were dependent on the nobles and largely servile to their unilateral interests, not the public good. By one account, there was not one bridge built or fixed in all of Sicily for a two-hundred-year period.34 With the island's deep valleys and steep mountains, the lack of a proper road system further alienated the country peasantry from the urban landed nobility. The divisions within and among the classes of society (and Sicily's principal cities) ran deep. The conditions for lawlessness and violence were ripe as barons, gabelloti, merchants, and peasants all took the law into their own hands. There are historical accounts of noble families hiring armed bandits to settle scores against rival noble families in broad daylight in Palermo.35 Other accounts provide evidence that even justice was for sale, with nobles being able to buy their way out of criminal convictions and jail sentences.36 These criminal elements would grow and harden with time, and it can hardly be doubted that the seeds of the Mafia took root in this climate of lawlessness and injustice.

For one brief, shining period during the seventeenth century, there was a form of landholding that had the potential to create the conditions for an agricultural renaissance in Sicily. It was called the enfiteusi ("emphyteusis") and involved long-term leases (sometimes as long as twenty years) whereby the tenant farmer rented small parcels of land for his home and his farming. He also had the legal right to prepay the balance of the long-term lease and effectively buy this land. The word enfiteusi derives from a Greek verb that means “to plant and to graft.” In other words, this form of long-term tenancy gave the peasant farmer the opportunity to plant his crop, harvest it, and then select which plants to graft to improve his crop. This form of farming is precisely the kind that fosters the careful cultivation of grapevines and olive and fruit trees, with crop rotation and selection for quality improvement. This was the method of farming that in northern Italy and France permitted the selection of vine varieties and other crops for quality over centuries. The use of the enfiteusi was concentrated near Menfi in the Val di Mazara, Vittoria in the Val di Noto, and Mount Etna in the Val Demone. Nobles who acquired licenses from the ruling Spanish viceroys in Palermo created hundreds of new town settlements throughout the island built on this form of land tenancy in the 1600s. Sadly, this experiment in land reform did not survive into the eighteenth century beyond specific locales. Barons were desperate to revert to shorter-term tenancies that gave them greater protection against inflation. The degeneration of Sicilian agriculture throughout most of the island was ensured.

It is no coincidence, however, that in two of the areas where the enfiteusi leaseholds were most firmly rooted, Mount Etna and Vittoria, grapevines were systematically planted and wine production thrived through the end of the nineteenth century. Beginning in the late sixteenth century, the bishop of Catania, in his capacity as the count of Mascali, granted long-term leases in tracts of land on the fertile plain between the Ionian coast and the eastern slopes of Etna to bourgeois families in exchange for their payment of the tithe based on the land's annual production. These families, in turn, subleased parcels of their land to long-term tenant farmers, who transformed Mascali from an uncultivated forest into the flourishing wine zone that it became by the eighteenth century. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Mascali had more land under vines than any other area of Sicily and was a vibrant center for wine production and export to England, Naples, and Malta. Mascali's success as a wine-producing area created the conditions for the freer flow of capital and a nascent middle class to take hold. In the growing towns of Giarre and Riposto, wine merchants, barrel makers, shipbuilders, artisans, shopkeepers, lawyers, and other professionals all played vital roles in strengthening the agricultural and maritime economy of Mascali during this epoch.

From the beginning of the eighteenth century through the first half of the nineteenth century, three succeeding foreign powers, the Piedmontese, the Austrians, and the Bourbons, recognized the need for fundamental, islandwide reform in Sicily. They had concluded that with its fertility and other natural resources, there was no objective reason for Sicily to be destitute. The island exported raw materials such as silk, cotton, sugarcane, and sulfur as commodities to overseas commercial industries, only to buy back the finished goods at a premium. Four principal reforms were required. First, the rule of law would have to be restored and enforced if Sicily ever hoped to develop the conditions for entrepreneurship and commerce. Second, land reform would be required to improve the agricultural economy in Sicily. Third, Sicily would need a public infrastructure of roads and bridges to facilitate the movement of people and goods. Fourth, the hundreds of different weights and measures used across the island would need to be made uniform. In response to the various reforms proposed by these successive foreign rulers, the Sicilian baronage actively resisted and ultimately defeated any changes that would diminish its own wealth or stature.

The Sicilian nobles were extravagant consumers of foreign luxuries such as clothing and wine. With limited exceptions, they had the affectations and pretenses of northern European nobility without the commensurate education or culture. They imported French chefs, called monzù, for their kitchens and French wine for their cellars. Rather than improve domestic sugarcane production by allowing the imposition of an import tax on refined sugar, the Sicilian nobles refused any such reform that would raise the price of their most precious imported commodity. In 1839 Sicily spent twenty-five times more on sugar than coal.37 The Sicilian nobles jealously vied for social status based on the outward demonstration of wealth, not its production. A continuous cycle of social engagements—weddings, baptisms, promenades, balls, theatergoing, gambling, religious festivals, funeral ceremonies—consumed the competitive zeal and precious capital of the Sicilian nobility. As a class, they demonstrated little attachment to the people or fruit of their lands, just the lavish trappings bought (and more frequently borrowed) with its revenue.

With the exception of select Sicilian nobles and clergymen who vigorously improved their lands and advanced the science of agriculture in Sicily, the larger story is of a noble class that abandoned its responsibilities to the land. At a time when the ruling classes of England, France, and Germany were embracing revolutionary improvements to the sciences of agronomy and botany and increasing their agricultural output dramatically, the landed nobility of Sicily were robbing Sicily and its true farmers of their agricultural patrimony.

In his iconic novel The Leopard, Giuseppe di Lampedusa (himself the last prince of an old-line impoverished noble family on the verge of extinction in the late 1950s) provides a nostalgic look at the fading baronial class on the eve of Sicily's unification with mainland Italy in 1860. The protagonist is the prince of Salina, Don Fabrizio. He is the Leopard of the novel's name, an archetype of the noble class that had ruled Sicily since the fall of the Norman/Swabian kings. He dabbles in astronomy and neglects the productive use of his vast lands. In the center of the book, the Leopard is offered the opportunity to become a senator and represent Sicily in the national parliament of the newly unified Italy. In declining this honor, he declares that nothing in Sicily will ever change and that its history is doomed to repeat itself. In his flowery soliloquy, he states that “in Sicily it doesn't matter whether things are done well or done badly; the sin which we Sicilians never forgive is simply that of ‘doing’ at all.”38 This is Sicilian fatalism in its purest form. The Leopard's words are often quoted, even by modern-day Sicilians, as prophetic. But they are not. The Leopard of Lampedusa's book is not the sympathetic Burt Lancaster figure of Luchino Visconti's film. He is no prophet. He is the ghost of Sicily past, a man of great privilege who, in keeping with his decadent class, has squandered the opportunity to do something fruitful with his life.

When the reader first meets the prince of Salina in chapter 1, it is in the formal garden of his Palermo palace. “It was a garden for the blind: a constant offense to the eyes, a pleasure strong if somewhat crude to the nose. The Paul Neyron roses, whose cuttings he had himself bought in Paris, had degenerated; first stimulated and then enfeebled by the strong if languid pull of Sicilian earth, burned by apocalyptic Julys, they had changed into things like flesh-colored cabbages, obscene and distilling a dense, almost indecent, scent which no French horticulturist would have dared hope for.”39 Lampedusa's vivid description of the rotting garden is the perfect metaphor for what the garden paradise of Muslim and Norman Sicily had become in the intervening centuries. When the prince of Salina visits his country estate in the second chapter, he wanders through the garden gazing at the nude statuary and lost in his aimless musings. It is his young and vital nephew, Tancredi, who calls to him to take notice of a grafted peach tree that has yielded beautiful fruit.

“Uncle, come and look at the foreign peaches. They've turned out fine.” . . . The graft with German cuttings, made two years ago, had succeeded perfectly; there was not much fruit, a dozen or so, on the two grafted trees, but it was big, velvety, luscious-looking. . . .

“They seem quite ripe. A pity there are too few for tonight. But we'll get them picked tomorrow and see what they're like.”

“There! That's how I like you, Uncle; like this, in the part of agricola pius—appreciating in anticipation the fruits of your own labors.”40

The “foreign peaches” are an exquisite symbol of Sicily's promise as a garden paradise governed by dutiful farmers (singular: agricola pius) who appreciate the fruits of their labor. In direct contrast with the prince's oft-quoted speech about the irredeemable Sicily, this small scene and Tancredi's simple words reveal what could have been a true path for Sicily's redemption. Unlike the French roses in the prince's Palermo garden, which had been left to wither in the blistering heat, the foreign peaches in his country garden are the product of the gardener's careful selection and a symbol of practical agriculture (as embraced by the foreigners of northern Europe, such as the English, the French, and the Germans). The prince seems disappointed by the small yield, but Tancredi intelligently appreciates the fruit's quality. At the end of this scene, the prince glimpses Tancredi's servant bringing a “tasselled box containing a dozen yellow peaches with pink cheeks” as a gift for the local beauty—who also happens to be the daughter of the mayor, a local strongman and the biggest new landowner in town.41 Even if only in symbolic terms (in place of the prosaic dozen roses), Tancredi surely sought to convey an enlightened noble's appreciation of his land and its promise with this offering.

One Sicilian noble who was guilty of the “sin of doing” was Prince Biscari, the antithesis of the fictional prince of Salina. In the eighteenth century, Prince Biscari, Ignazio Paternò Castello of Catania, personally funded the construction of an aqueduct to reach his rice fields, excavated the ruins of a Greek theater, created one of the most respected private museums to showcase Sicilian antiquities and natural history, imported foreign artisans to bolster the local production of linen and rum, and largely fed the entire city of Catania for a month. His palace and museum in Catania were must-sees on most grand tours in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Prince Biscari surely was more deserving than the prince of Salina of the moniker the Leopard.

During Sicily's wine-dark ages there were other real-life Sicilians—nobles, clergymen, farm managers, peasants, and other boni homines—who contributed magnificently to their land and its culture. Antonino Venuto, a farmer (agricoltore) from Noto in southeastern Sicily, authored the first agricultural treatise in Sicily to focus exclusively on the cultivation of fruit trees and vines, De Agricultura Opusculum. This work, first published in 1516, has individual chapters for twenty-five types of fruit trees (including orange, mulberry, cherry, carob, fig, pomegranate, almond, pear, and apple) and an eight-chapter “treatise about vines and the soil they like,” describing how to plant, prune, and propagate grapevines.42 Another distinguished Sicilian from the sixteenth century was a Dominican friar named Tomaso Fazello. Fazello discovered ancient Greek ruins in Agrigento, Palazzolo Acreide, and Selinunte and wrote a multivolume history of Sicily from its earliest age. The work is a thousand-page tome called De Rebus Siculis and was published in 1558. Fazello's first volume begins by extolling Sicily's rich fertility. He describes fruit trees and grapevines planted in the mountains, where the richness of the soil, the sweetness of the water, and the freshness of the air made them as fruitful in winter as in summer. While chronicling Sicily's place in ancient history, Fazello makes reference to the area of Entella, modern-day Contessa Entellina, as celebrated since Roman days for its wines. King Acestes's gift of treasured wine to Aeneas comes to mind. Fazello states that by his time, Entella had been all planted to grain and thus was ruined for wine.43 This observation echoes the historical record that many small farms in western Sicily formerly planted with vines and olives were consolidated as part of latifundia planted almost exclusively with grain during this period. Regardless of this historical reality, Fazello claimed, whether from provincial or justified pride, that the Sicilian wines of his day were celebrated because they were as fine as any in Italy. He described them as sweet, soft, and good for the stomach because they were capable of long aging without the need for reinforcement with alcohol spirits.44 As evidence for Fazello's praise of Sicilian wine, a century before, King Alfonso, the Aragonese ruler of Sicily, commanded his Sicilian officials to send the wines of Trapani, Corleone, Aci, and Taormina to his court in Naples to prove they served him well. The wines he ordered from Trapani and Aci included “some newly pressed, some two to three years old and some ‘of the oldest you can find.’ “45

What is known about vine varieties and wine production in seventeenth-century Sicily comes directly from the written works of two other distinguished Sicilian clergymen, Francisco Cupani and Paolo Boccone. Cupani was a Franciscan botanist in charge of a botanical garden outside Palermo. He is the author of a book titled Hortus Catholicus ("Catholic Garden"), which was published in 1696 and formally classified Sicilian plant and vine varieties. Boccone was a Cistercian monk from a noble family who, prior to his entry into the Cistercian order, had been a professor of botany at the University of Padua and the official botanist for the grand duke of Tuscany. He wrote more than a dozen respected works on botany, including a classification of Sicilian flora.

At the end of the eighteenth century, a Sicilian clergyman named Abbot Paolo Balsamo became the first professor of agricultural science and political economy at the Royal Academy in Palermo. Balsamo had spent three years studying advanced agricultural methods and rural economics in England and France. He returned to Sicily armed with the conviction that his island home was capable of achieving agricultural excellence, asserting that if Sicily were “cultivated with the same attention and care with which England, for example, is cultivated, it would certainly produce at least four times more than it does at present.”46 In a published journal reporting on the state of agriculture in Sicily in 1808, Balsamo exhorted Sicily's landowners and farmers to dedicate themselves to “every sort of useful cultivation” based upon a “real love of the soil.”47 He describes a former feudal property that had been divided by order of the Bourbon king among many small tenant farmers. Prior to this division, the land “was wild and desert, and nearly a third of it barren and uncultivated, and from that time it has so changed in appearance and become so rich in farm houses, trees and shrubs of various sorts, that it may now be called one continued village, and one of the most delightful retreats. . . [, and] of the plantations that of the vine is beyond comparison the chief.”48 From this experience, Balsamo concluded that “the culture of the vine is superior in effective value to that of corn,” provided that the soil is adapted to it, the land is not too expensive, and the wine finds a ready market at a reasonable price.49

A Sicilian baron named Filippo Nicosia was one of Sicily's truly noble farmers. In 1735 this baron of Sangiaime published a manual on arboriculture that distilled decades of his personal observations and field experience. The book, called II Podere Fruttifero e Dilettevole ("The Fruitful and Delightful Farm"), paid homage to the glories of the fruit orchard and the cultivation of grapevines (probably not a book in the Leopard's library). As a young man, Baron Nicosia had inherited his country estate in the center of Sicily (near Enna), and instead of taking up residence in Catania, where his noble family had its origins, he went to live on and improve his farmland. He was among the first Sicilians, following Venuto, Cupani, and Boccone, to treat the science of agriculture in a serious written work. He understood that agriculture was the foundation of Sicily's wealth, and he dedicated himself to its betterment. Baron Nicosia represented the ancient Greco-Roman ideal of the agricola pius, who appreciated the fruits of his own labors. In tending his trees and vines with his own hands, he could never have been mistaken by any latter-day Odysseus as part of that arrogant race of Cyclops who planted nothing and plied no plows. While the Age of Enlightenment largely bypassed Sicily, there were Sicilians of both noble and humble birth who advanced their island's culture and carried the torch for Sicily during these wine-dark centuries.