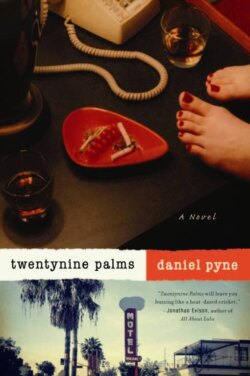

Читать книгу Twentynine Palms - Daniel Pyne - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеone

The merciless heat.

The whine of tires on asphalt, growing louder, louder, louder, loud.

A blue belly lizard charges up out of a rivulet creasing the pebbles of the shoulder, skitters to the broken line of white paint that splits the black road in two. It cranes its neck, head jerking up and down, jowls flaring, its tiny heart pumping wildly, its eyes narrow slits of fierce darkness and abject fear. The girl who sent the lizard running walks past, feet scuffing pebbles, her path taking her tight along the shoulder of the road. She doesn’t see the lizard. She’s fourteen, overheated, not really pretty yet, sundress, spandex, Day-Glo zinc oxide striped on her nose and cheeks like war paint.

Her icy blue eyes squint to study the horizon, hopeful, behind egg-shaped sunglasses. The heat comes up through the soles of her Converse All-Stars and sears her feet. She shifts the small Hello Kitty backpack to her other shoulder and takes a swallow from her big bottle of purified water.

Mechanical bumblebee sounds buzz from her backpack. Reaching to a side pocket and finding a flip phone, she has to cup her hand and shade the screen to read the text:

heyyyysup?

The salutation and question. Small fingers flick across the keypad of the phone and text back:

ssdd.

Same stuff, different day.

She senses the car behind her before she hears it. She turns around, legs still pushing her east.

What seems only a mirage—a dazzling black cartoon car—suddenly materializes out of the shimmering puddle of heat distortion on the highway horizon and hovers over it, growing quickly larger. Blaring rock-and-roll music from open windows, the car, a Buick sedan, races forward, at, then directly over and past, the blue belly, its life spared by a miracle of time and place.

The lizard tumbles wildly in the wake of the car, fifty, sixty feet down-highway. Its tail separates from its body, a useless tactic of survival that here only serves to cheat the creature of future mobility, and probably hasten its surrender to the food chain.

Thumb out, the girl watches the Buick whip past her, tossing her hair and dress around. No brake lights, it’s not stopping. She smoothes her dress, fixes her hair, keeps walking.

Her bumblebee ring tone offers comfort:

wysiwyg.

What you see is what you get.

A falcon swoops across the highway, catches the blue belly in its talons, and soars again gracefully out over the brown desert. The lizard thrashes desperately, and in doing so executes itself on the point of a sharp talon.

The girl never sees it, walking and texting:

iyss.

If you say so. And then, an afterthought:

icbw.

It could be worse.

The falcon settles lightly on the top of a broken knob of rock, high on the hill above the highway, and eats a late lunch in the afternoon sun.

r u ok?

gr8. 404. nbd.

kewl.

yup.

The screen indicates no service. The battery icon flashes, low. She folds the phone and puts it away.

A few miles west, on either side of the highway, modular slant-roofed homes squat defiantly on their parceled acres of Mojave Desert. Fierce-looking, wind-whipped zealots with rusted TV aerials for hats, they wait for the God of Fast Food Chains and Mini-malls to send property values skyrocketing, or for the Big Earthquake to put them out of their misery. Higher up, in the ragged hills among giant, broken, burnt-orange boulders turned bloody by the sun, the larger stucco tract homes with industrial air-conditioning and polarized windows and upside-down loans gaze back emptily at traffic that hurries past as if embarrassed.

Joshua trees, thick and spiny thugs with multiple arms held aloft, swarm in from the south in an outrage at the invasion of men; tens of thousands of trees storming the interlopers’ highway and then retreating into the barren, scraped-out, labyrinthine valleys to the north, where the poor subsist, and the wealthy hide their multi-million-dollar desert homes, and where, at the end of a rutted road, Tory Geller and his wife Hannah have thirty-five acres and a purposefully crooked house designed by a famous young Chinese architect.

Inexplicably, just beyond the RESUME 55 speed-limit sign that establishes the eastern boundary of Joshua Tree city proper, the horde stops short, as if what lies ahead, in Twentynine Palms, discourages it. The only Joshua tree in Twentynine Palms is planted in the asphalt courtyard of the Rancho Del Dorotea motel, right next to the bleached turquoise swimming pool.

Jack cannot see it from his balcony.

The balcony in Room 203 looks west, to the lurching litter of civilization that is Joshua Tree and Yucca Valley, strung together like cheap plastic jewelry along Highway 62. It makes Jack smile.

He considers the dying day, and the lights beginning to glow across the desert, and for a moment he can’t remember why he’s here. Sometimes the world is clear to Jack; sometimes it’s an impenetrable abstract of shapes, colors, vectors, and emotions, strange values and stranger contrast.

His shirt is soaked through. The rasping of crickets soothes him. From his pocket he takes a pack of filterless cigarettes, then a platinum lighter, fires up and smokes, holding the cigarette between his thumb and forefinger like a movie star. After a moment, he balances the cigarette ash-up on the balcony railing, and starts to unbutton his shirt.

Inside, the air-conditioning control knob is broken off, stuck on the highest setting, blowing frigid air, while the open balcony door blows desert heat. Jack strips to the bathing suit he’s been wearing since he left Los Angeles. There are those thin, abrasive motel towels in the bathroom. He finishes his cigarette, flicks it off the balcony in a shower of ash, then closes both doors and walks down the stairs to the pool to take up residence under the solitary Joshua tree, on a vinyl-woven chaise that is almost brand-new.

For a few minutes he’s still hurtling down the highway. With his eyes closed Jack can feel the speed, conjure landscapes to flicker past in his peripheral vision.

Slowly, his body sinks into the warm plastic webbing, and he brakes. A liquid heat washes him. He arranges the towel over his eyes, inhales the pungent smell of industrial laundering and disinfectant. The setting sun scrapes its hot needles across his skin. Now, finally, perhaps he will sleep.

“Zach. Zachary, don’t you go in the deep end!”

Splashing sounds bring Jack to consciousness under the towel. He’s missed sunset, and the desert sky glows cobalt blue. Pale orange neon lights that rim the eaves of the motel are sputtering to life.

Jack adjusts the towel. The water in the pool at his feet is choppy, someone in it, splashing.

“If you go into that end, young man, we’re going back inside.” A woman’s voice ricochets, hollow, around the concrete courtyard, followed by more splashing, and a child’s imitation of an outboard motor. Lips to water.

“Zach—”

Jack doesn’t look up. He doesn’t need to. He paints a mental picture of the pale, plump woman with jet-black perm standing flaccid-thighed in plus-size swimwear at the end of the pool, glowering as her little tyke flails his way toward the five-foot mark, deaf to her threats. Former high-school prom princess turned pumpkin, her lips flattened into a humorless slit. Foam flip-flops slap over wet concrete, water churns—

“Ooowww!”

“You heard me.”

“That hurts!”

“Out.”

“I could still touch bottom.”

“Let’s go.”

The boy’s reluctant, soggy footsteps recede into the shadows, and Jack sits up in time to catch the greenish-white, fleshy backs of a woman’s legs as she leads her son toward a unit on the ground level, at the far end of the motel. Her white shorts gleam iridescent, lit from below by the pool lights.

What is Tory’s theory? Something about women, marriage, children, the time bombs mothers plant deep inside their daughters; hard body spoilage, breasts drooping, butts dropping, faces inflating like bread dough, the tight hats of sensible hair, car pools, Botox, and the desperation. Jack rises from the chaise and leaps out over the pool, arching his back, knifing into the tepid water.

Opening his eyes to the sting of chlorine, Jack grazes the pool bottom with his stomach, and then lets his momentum bring him back slowly to the surface. The hot night air inexplicably gives him goose bumps.

Jack floats easily.

“I lost the sight in my left eye when I was twenty.” Three gentle taps to the business end of Jack’s unlit cigarette, then he spins it in his fingers, forestalling the inevitable trip outside to smoke it. “If you look close, the pupil is distorted. Like a teardrop. But I don’t consider myself disabled or anything. I don’t even think about it all that much anymore.” Salisbury steak is the blue plate special, and Jack ordered his at the bar. “You adjust,” Jack says, answering what he always assumes is the unasked question. “I’m supposed to wear glasses, clear lenses, for protection. Of the, you know, good eye.” Jack is making conversation, enjoying the thrum of his own voice. “I don’t know why I never have.”

The lean bartender nods, cutting limes.

“I see like a camera. Everything’s flat. Compressed. But if I move my head, slightly, like this,” Jack shifts imperceptibly, “I’m taking two pictures, my mind compares them, measures the difference, and I get my sense of depth.”

“Okay.”

“At first it was hard, though.”

“I know some soldiers, lost eyes in Iraq. They say they have trouble shaking hands. Parking the car. Chopsticks.”

“Chopsticks are tough for everybody,” Jack allows.

There are few customers tonight in the Roundup Room. Jack prefers the anonymity of his corner stool at the bar to the checkerboard-cloth-covered wagon-wheel tables for six and slide-in booths in the over-lit dining area. When was the last time, he wonders, there were six people having dinner together in here? Two couples, marines from the nearby combat training facility and their dates, are the only diners. The jarheads are having the all-you-can-eat popcorn shrimp, and their ketchup-splattered plates suggest it has become a how-much-will-they-cook situation. Three heat-jacked, love-shot, middle-aged gals sit in a booth with a pitcher of margaritas, sharing their perky loneliness. Another marine, older, in street clothes but with the unmistakable high-and-tight haircut, gunnery-sergeant set to his mouth, and intricate, indecipherable tattoos on both biceps, sits hunched at the opposite end of the bar from Jack, nursing a lite beer and occasionally glancing up, hopeful, at the door.

“I’ll tell you what, though,” Jack continues, unable, for some reason, to shut up, “it makes you greedy, about what you do see. It forces you to see more clearly. You don’t waste your time on the visual garbage. A man with one eye wants to focus on the things that are worth seeing.”

The bartender rolls out some more limes. “So I guess you spend your free time surfing porn sites on the web.”

“He’s a comedian,” Jack says, smiling. Shut up, Jack tells himself. Shut up, go outside, have your smoke.

Salisbury steak with Brussels sprouts and cactus shavings is an attempt, Jack guesses, at nouvelle Western cuisine. He eats hungrily, without thinking about it. It’s his first meal since an Egg McMuffin and Diet Coke breakfast, on the grey, fog-bound road back from Santa Barbara at dawn.

For a moment he wonders if he dreamed it.

“Been out here before?” The bartender is bored. Just grinding through another shift.

“I’ve got this friend, married a swimsuit model. She’s filthy rich and they’ve got a house in the north hills. Usually I stay up there.”

“Not this time?”

“No.”

“Swimsuit model. That’s sweet.” Jack pushes his plate back, politely trying to put a punctuation on the conversation, but, apropos of nothing, now the bartender waxes on: “Before he got married, my cousin Cody was, like, this major poozle hound. He had a theory that, before you get serious about a girl, you want to meet her mother. Seriously. Because, according to Cody, the mom is what she’s going to look like when, you know, the fruit goes past ripe.”

“Past ripe.”

The bartender smiles. “Hey. Two pictures.”

“What?”

“Two pictures, one eye. Like you were saying. It’s the multiple pictures that give you the depth of perception.”

“It’s bullshit, though,” Jack says. “Don’t you think?”

The bartender shrugs, suddenly on the defensive for his cousin. “So, your friend, did he ever meet the swimsuit girl’s mother?”

Jack thinks. “He did, yeah.”

“And?”

There’s a commotion in the kitchen. Raised voices, pans clattering. Everyone in the restaurant pretends not to notice. The bartender takes Jack’s empty plate away and replaces it with a cup of coffee and brandy snifter filled with two fingers of Sambuca. Jack swirls the glass, trying to rinse a stray bean back down with its buddies.

Abruptly, the kitchen doorway bangs open, a lanky cook appears pushing ahead of him a sullen girl with a Hello Kitty backpack. He scolds her in Spanish, she says nothing, her Day-Glo sunscreen smeared across her cheeks, her unscreened arms sunburned painfully red. The girl just stares at her feet until the cook gets tired of yelling and goes back into the kitchen with a sense of finality.

“Hey.”

The girl looks up and locks eyes with Jack.

“I’m Jack. What up?”

The front door opens and closes on Jack’s blind side; Jack glances toward it out of habit, and discovers he can’t stop looking at the young woman who enters, his breath literally caught for an instant in his chest before he remembers to breathe again, she’s that pretty.

“Rachel,” the Hello Kitty girl tells him, but Jack’s not listening anymore.

Hitching up her short green dress, the woman lifts herself onto a bar stool halfway between Jack and the marine sergeant. Her legs cross gracefully to let one green high-heeled pump dangle. Then she takes it off, puts it up on the bar, and rubs her foot.

“These shoes are murdering me,” she says. The bartender pours her a Wild Turkey straight up. “No wonder they call them Fuck Me pumps.”

The bartender laughs. The young woman in the green dress manages to look around the entire room without making eye contact with Jack.

“I heard about a guy who makes a thing you can put in the heel to make them more comfortable,” the bartender is saying.

“That’s pretty vague. A guy? A thing?”

“Didn’t occur to me to take notes.”

“Ha ha.”

“I thought you were going dancing in Victorville tonight.”

“I thought this all-you-can-eat shrimp deal was supposed to draw customers.”

“Talk to the boss, m’lady.”

“Yeah. As if.”

They both laugh.

Jack pretends to study the oil-swirls in his coffee, so she won’t think he’s staring. But he is, staring. The dim light that falls on her from old recessed spots softens her face to a pleasant blur of pinkish white framed by dark hair that folds to her shoulder. Smudges of mauve eye shadow, serious, impenetrable eyes. A slur of lavender lipstick betrays the sad smile.

One of the old gals, slender, white-haired, stands up with the empty margarita pitcher and brings it to the bar for a refill. Jack tap-taps his cigarette again.

“Excuse me. The girl who just came in—”

Both the bartender and white-haired woman glance at Jack, wondering if he’s talking to them. Jack waits. The older woman smiles, self-conscious. Jack smiles back. The bartender refills the pitcher, delivers it, and looks at Jack. “Yes sir?”

“I’d like to buy her a drink.”

“The girl?” The bartender’s eyes shift to Rachel, still waiting, behind Jack, having so recently evaporated from his landscape that it takes him a second to realize where the misunderstanding could be.

“No, no—” Jack tilts his head toward the young woman in the green dress and meets the bartender’s expressionless gaze with an easy smile.

The bartender tightens his lips. “Okay, one: don’t call her a girl, she won’t like it. And, two: you’ll have to ask her first, because, as you may have keenly observed with your single eye, my friend, I know her and I don’t want to piss her off. She’s ferocious, when she gets pissed.”

Jack blinks.

The older woman turns with her Margarita refill to go back to her friends. Her feet get tangled. She starts to fall. Jack reacts, grabs the pitcher—it sloshes, doesn’t spill—and simultaneously catches her by the arm, gallant. The old gal’s friends spontaneously applaud, delighted. Jack steadies the woman, hands her the pitcher.

“You all right?”

Blushing fiercely, she nods, “Fine. Yes. I’m—sorry. My feet . . .” Jack cuts his eyes toward the young woman in the green dress again, but discovers Rachel and her backpack sliding purposefully onto the stool beside him, directly in his line of sight.

“Rachel,” she says.

“I know. I heard you the first time.”

“Oh.” She catches the bartender, “Hey, can I have some water, please?”

The bartender frowns, annoyed. “I have to charge you a dollar.”

“For water?”

“Put it on my tab,” Jack says.

The bartender looks at him a little irritably, and moves away to get a glass.

“Thanks.” Rachel studies Jack for a moment, critically, as if he were a math problem, then picks at the nail polish on her thumb.

“Where are your parents, Rachel?”

“I’m not supposed to talk to strangers,” she says in a rote monotone.

The marine sergeant slides heavily off his stool and walks over to the woman in the green dress, who stares straight ahead, measuring his approach in the mirror. Sipping her whiskey and shaking her head slightly in response to whatever the marine is asking her, she never stops smiling, even when the sergeant steps back, almost as if slapped, and runs his thick hand across the level playing field of his flattop. Regrouping, he asks something else. She turns to him, her whole body facing him, and talks to him kindly for a moment longer.

Jack watches this, his heart in his groin. And then, shamelessly, he commits himself, suddenly, predictably, to wanting this woman as much as he has ever wanted anything; to fold her into his arms, soothe the disappointment from her smile, to move into one of those slant-roofed shacks on two hundred acres of barren desert, homestead, depurate himself, court her, win her, earn her. Well, and sleep with her, yes, but—it plays out for him in fast-forward, like a Lifetime channel TV movie, and, Jack realizes with the usual tinge of disappointment, that it actually was a Lifetime movie, a ten-hankie chick flick in which he played the part of the foolish marine who never stood a chance.

Jack wants to sleep with her, and he knows from experience that he probably will, it’s just a matter of mechanics now. The real sergeant has retreated, fallen back to his stool and beer and is standing there, looking at nothing, square shoulders round, defeated. The young woman in the green dress sips her drink, nonplussed, eyes straight ahead again. Jack considers his opening gambit.

Serendipitously, Rachel, petulant and feeling ignored, takes the glass of ice water the bartender has delivered and tilts decisively off her stool; she stands directly behind Jack and pours most of it down the neck of her sundress, front and back. Water splatters onto the waxed, worn linoleum under her feet.

She’s got Jack’s full attention now. She’s got the whole restaurant’s attention. She makes a squeaking noise. The water is cold.

“The hell are you doing?!” the bartender growls, and starts to come from behind the bar, but Jack intercepts him calmly, acutely aware that the woman in the green dress must be watching all this, too.

“I’m sorry. She’s with me,” Jack says, about Rachel. “It’s okay. She’s my sister.” He takes the towel off the bartender’s shoulder, tosses it at the girl’s feet and starts to mop up the ice water. “She’s got—issues,” Jack is ad-libbing, and he says this loud enough to be heard halfway down the bar. “Impulse control issues. I’m really sorry, man. I’ll clean it up.” The old ladies in the booth are buying it, their faces showing sympathy and relief (that Rachel isn’t their problem). The bartender knows it’s bullshit, but seems relatively disarmed by Jack’s complete commitment to the role. The jarheads never look up from their plates, just want to eat before the shrimp gets cold; their dates look like they will probably believe anything.

“Are you hungry?” Jack asks Rachel, for the benefit of his intended audience just down the bar, but she’s on his blind side and Jack can’t tell if the woman in the green dress is even paying attention anymore.

“A little,” Rachel says, going with the performance.

Jack flags the waitress, who’s hurrying past with empty shrimp plates. “My sister wants to order some dinner,” he says. “Can you put it on my tab?”

“You like shrimp, hon?” the waitress asks absently.

Rachel shivers, cold, her dark eyes never leaving Jack. “Deuteronomy 10: ‘And whatsoever hath not fins and scales ye may not eat; it is unclean unto you.’”

“’Scuse me?”

“It’s against my religion.”

“Shrimp?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“And your religion is—?”

“No shrimp.”

The woman in the green dress laughs out loud. The waitress shoots a slightly wounded look at her, and lets it slide contemptuously across Jack and Rachel before retreating into the kitchen. “Why’nt you look at a menu, I’ll be back.”

Jack nods at Rachel. “Have a seat. Sis.”

Rachel’s mouth is an ineluctable straight line. “Okay. Bro.”

He gestures to a booth. She picks up her backpack and crosses to a banquette, where she flops down to wait, wet, staring grimly back at him. No one else in the restaurant meets her wandering gaze.

“You coming?” she says, innocently. He pretends he doesn’t hear her.

Barely another moment passes before the pretty young woman stands up, smoothes her green dress, takes her glass and her shoe and limps, one shoe on, one shoe off, down the length of the bar to sit next to Jack. She still hasn’t looked at him.

The marine sergeant drains his beer.

“I’ve seen some elaborate flirting in my time,” the woman says, “but that was positively Baroque.”

Jack smiles at her. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

The woman in the green dress puts her shoe between herself and Jack. “I noticed you earlier. Out by the pool, under the tree. L.A., no?” Now she looks at him.

“Yes.” But Jack feels the need to qualify it, “Santa Barbara, originally. I’m Jack Baylor.”

“Mona Malloy. Nice to meet you, Jack.”

The waitress returns from the kitchen with an order pad and crosses to the booth where Rachel is fiddling with her cell phone. The bartender asks Jack if he’d like some more coffee. Jack nods and notices, back down the bar, two bills left alone on the counter where the marine had been sitting. He is already gone, the door swinging shut behind him.

Game, set, match.

“That girl’s not really your sister, is she?”

They both look at Rachel, who raises her phone and takes their picture.

“No, she’s not,” Jack admits, grinning winningly, he thinks, and then, before he can stop himself, asks, “The jarhead give you any trouble, Mona?”

Mona’s eyes flash amusement. “Why? Were you gonna come to my defense, too?”

Fuck! Jack thinks. “If it came to that,” he says, trying to salvage his play. Jesus. Shut up.

“You ever fought a marine, Jack? Even a fat, drunk one?”

Jack has still never swung, in anger or in fear, at anyone in his life. There was the one time, with Tory, but that wasn’t a fight, as it turned out. “I took some Hapkido.”

“Is that like Kung Fu?”

“With the sticks.”

“Oh.”

The Hapkido lesson was a special offer at the Fat Burn Easy spa down on Oxford, in Koreatown. At the urging of Jillian, his pre-Hannah Best Friend with Benefits, Jack joined for six months when Jillian had him convinced he was starting to put on weight. Jillian, as it turned out, never joined at all.

“Like Jet Li,” Mona says.

“I’m in pretty good shape. I think I could hold my own.”

Mona laughs. Jack feels the playing field tilting away from him. If he were actually standing on it, he’d be tumbling downslope, away from her, like a cartoon character. This is not going the way he needs it to.

“Pretty good shape? You look like you’re in terrific shape. Mr. Ripply Abs, Bowflex, Buns of Steel.” She leans into him, casual, her shoulder almost touching his, “But, see, fact of the matter is that old leatherneck, Sergeant Symes? He did three tours in Kandahar, blew out his back, got a medal and a medical discharge, and lives out in a desert double-wide, and all day long he’s ex officio over at the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center, training young warriors and thinking about nothing but fighting and killing and getting laid, Jack. In that order. So if he decided to bother me, and you decided to come to my defense, it would probably be a very brief and unpleasant thing. And I’d probably have to step in and save you.” Mona finishes her drink, one big swallow. “Which wouldn’t play at all, would it?”

The middle-aged gals are leaving, tipsy, calming their weepy red-eyed friend, the one who bought the last round and nearly did a face-plant; their cosmetic laminate crinkling and those slurry, collagen smiles, sneakers shuffling across the tile floor, thanking the bartender, brushing limp, sweat-heavy bangs of their sagging perms off their faces. In her booth, Rachel pokes at a vegetarian omelet, sleepy, and tries to text something into the void. No battery. Jack shifts uneasily, figuring Mona’s about to tell him to take a hike. He can’t read her. Everything’s gone flat. Mona stares at him until he feels about two inches tall. Then she looks away, into her empty glass. The sadness in her smile.

“I guess you won’t want me to get you another one of those?” he says softly.

Mona turns her head profile, and looks at Jack curiously out of the sides of her eyes. As if he’s suddenly come into focus.

“No,” she agrees, “no. Not if you won’t stay until I finish it.”

Half a cigarette, balanced ash-up on the edge of a bed stand, glows.

Making a suction sound as it comes off his foot, taking the sock with it, Jack’s antique cowboy boot clunks loudly to the floor and flops on its side. The second boot gives up without a protest. Mona drops it, then pulls off the remaining sock with her fingertips, nose wrinkling.

“Larry Mahan,” she says.

“Huh?”

Jack lies stomach-up on the bed, takes another drag on his cigarette. He’s where he wants to be, and yet didn’t get here in any of the usual ways. Tilt-a-Whirl, he thinks. I’m riding the ride. Mona rocks her hips back, straddles his legs, facing his feet.

“Your boots. Those are Larry Mahan boots. He was World Champion All-Around Cowboy for a few years running, back when bull riders wore Stetsons instead of helmets and the clowns were all drunks. Larry Mahan had a whole line of clothing named after him, hat to boots.” Mona crawls up the bed and flattens herself against Jack’s chest. “I recognize the boots by the smell.”

“I thought that was just my feet.”

“Nope.” The straps of her faded gumball-pink brassiere have dug softly into her shoulders and back. Her pale skin shows crease marks from her clothes. Jack runs his hand along her side, up under the lace and silk of her underwear. “Everybody’s feet smell the same in Larry Mahan boots,” she says, shivering.

“A voice of experience.”

“Lots of guys want to be World Champion Cowboys, Jack.”

He traces a small tattoo on her hip: outline of a heart, thin lines blue as a vein, with the faded red promise “Always Faithful” scrawled through it on a curled banner, in script.

“The helmets have ruined it,” she adds.

Her lips are dry. They skate across his neck, and down his breastbone, and over the slight rise of his stomach. Hair dusts his hipbones. Her slender hands slip under him, cool, and gentle. He feels everything and nothing. She moves slightly, adjusting her body. Small, tight breasts settle on his thighs. He strokes her neck.

There is, in the aching quiet, the dry trill of heat-dazed crickets in the vacant field behind the motel. There is the dry trill of crickets in the bush muhly and the desert needle. There is the dry trill of crickets and the promise of another day.