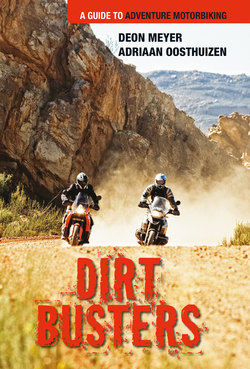

Читать книгу Dirt Busters - Деон Мейер - Страница 6

ОглавлениеIntroduction – Deon Meyer

‘What’s so great about riding a motorbike anyway?’

That’s the question I get asked time and again, usually accompanied by the same sceptical look children have on their faces when their mother lectures them about the nutritional value of Brussels sprouts. In the past, when I still believed it was possible to describe the endless pleasures of motorbiking in words, I always started with the story of the elephant.

Dave Briggs and I passed through the border post at Chirundu far too late one afternoon, thanks to a bothersome Zimbabwean customs official. Dave was on a K75, I on my old R1100 GS. We had to be at Kariba before sundown because in northern Zimbabwe you don’t ride in the dark – there are buck and bushpigs, cattle and horses to contend with, not to mention the hazards presented by pedestrians.

So we went full throttle. Just before the turn-off to Mana Pools National Park we came around a wide bend at 150 km/h and there he was in the golden light of an African dusk: a giant elephant bull, casually strolling across the road. We really had only one choice, since it was too late to brake: we had to slip past his trunk on the narrow strip of tar left between ivory tusks and the edge of the road.

For that instant, captured by our synapses like a cerebral Kodak moment, we were right in front him, next to him. We could see the wrinkles on his rough skin, his big, black eye and those incredibly long eyelashes, and, I swear, we could even smell his elephant scent.

‘You’re saying it’s about the adrenaline rush,’ people would pronounce after hearing this story, needing a label.

Yes, sometimes it is about the adrenaline, I would answer patiently. Sliding down an impossibly steep slope of some obscure jeep track, rear brake locked, squeezing the front brake as you try to navigate stones and gullies … yes, it’s pure, undiluted adrenaline. But that’s not really what it’s all about.

‘So what is your thing then?’

Bikes for adventure touring. And then I would start to prepare for the inevitable explanation as you see them struggling to grasp what you mean. These are motorbikes, I’d say, which are made to perform as well on tar as on dirt roads. Even in the roughest of African terrain, like that footpath across the Makatini Flats along which legendary off-road instructor Jan du Toit led us, thorn branches whipping our shoulders, as we navigated ditches, curves, streams …

These bikes have panniers with enough room for a tent, sleeping bag, gas lamp and provisions, and they are built for long-distance comfort with a broad, firm seat and a shield to keep off the worst of the wind. On the gravel road you need to stand up for better control and the footrests and handles are designed so that you can do this for hours at a stretch.

‘Sort of like a four-by-four.’ I would actually see the lights go on.

Only better, I’d say.

‘Oh?’

Then I’d tell them about the early-morning ride Jan and I took through the Namib. How I felt the chill desert breeze against my skin and smelled the faint scent of grey grass and quiver tree and damp sand. We rode from Aussenkehr, following a dry stream bed into the valleys to the top of the mountain, where the plateau opens in a gentle curve in front of you. A herd of springbok suddenly joined in the game, cutting in behind us, then running with us, bouncing and tossing their heads playfully, before vanishing just as swiftly as they’d appeared. A moment so magical that we stopped, switched off our engines and sat there smiling wordlessly.

Or I’d tell them about splashing through the rivers of the Baviaanskloof with my wife, Anita, every sense engaged. You hear the shurrrr as you push through the streams, see the spray glinting silver in the sunlight. You smell the fruitfulness of earth and feel the cold, wet mountain water as it splashes through the raised helmet visor.

You go places that even 4×4s can’t – like the sandy footpaths between Melkbosstrand and the West Coast road, the spooky bluegum forest on Jan’s farm in Amersfoort and the swimming hole at Klipbokkop Mountain Reserve near Worcester. I describe, with growing passion, the thick, white sand of Mozambique. I explain how you can gallop with giraffe through the Pongola Game Reserve, explore muddy mountain trails on paunchy ridges protruding from Lesotho, beyond Rhodes. I so badly want them to understand, to fire them up. If they could only once share in the camaraderie of four or five or six motorbikes in high-speed convoy, or experience the sensation of a sliding rear wheel that you straighten out with the power of the accelerator round a curve.

But not everyone gets it. I never say so, but I think it must be in your genes. I imagine how a million years ago there must have been primitive people who, when they saw a game trail winding up a mountainside, felt an irrepressible urge somewhere deep inside them to follow it. Just to see what was on the other side and to keep on walking.

This, I suspect, is at the heart of the matter: the longing to discover remote places, to get away from the hustle and bustle and to feast on new horizons. The only reason the peoples of the Stone Age had to do it on foot was that adventure-touring bikes didn’t exist back then.

Over the years I have come to accept that my answers usually fail to convince people. When someone these days asks me what is so great about riding a motorbike, I smile politely and steer the conversation in a different direction. But, when I get home, Anita and I will spread out the road map and search for a faint, new line that begs to be followed.