Читать книгу Resurrection - Derek Landy - Страница 8

2

ОглавлениеWhen the bad thoughts crept up on her, and they did, they came slowly and quietly, slipping in unbidden to the back of her mind, and there they waited, patiently, for her to notice them.

She viewed them as if from the corner of her eye, hesitant to acknowledge their arrival and powerless to make them leave. They stayed like unwelcome guests, filling the space they occupied and spreading outwards. They slowed her down. They dragged on her, made her heavy. When she walked, her feet clumped. When she sat, her body collapsed. It was hard getting out of bed most days. Some days she didn’t even try. She knew what was coming.

She was going to die. And she was going to be on her knees when it happened.

She couldn’t see her death, but she could feel it. Kneeling down to change a car tyre, she had felt it. Kneeling down to clean up after she’d dropped a plate, she had felt it. Kneeling down to play with the dog, she had felt it.

This is how I’m going to die, she’d realised. On my knees.

And always, always, after this had occurred to her there came another thought, the thought that it had already happened, that she was already dead, that her body was growing colder and her blood wasn’t pumping any more. She experienced moments of pure terror when she believed, believed with everything she had, that she was trapped in her own corpse, that nothing worked and that no one could hear her screaming.

And then she moved, or she breathed, or she blinked, and with each new act of living she clawed her way back to the realisation that no, she wasn’t dead. Not yet.

It was mid-afternoon, and it was cold. The cold meant something. It was the last bite of the beast called winter, a beast that had stayed too long already. She could feel it on her face, on her ears; she could feel it seeping through her clothes. It meant she still had a spark of life flickering inside her. That was good. She needed that. But it also signalled a loss of focus, as she found it increasingly difficult to summon the crackling white lightning to her fingertips.

Eventually, she just sat on the tree stump on which she’d placed the tin cans she’d been using as targets. Three of them were scorched. Two were brazenly untouched. Still, three out of five meant that at least her aim was improving.

She hugged herself. It was an old hoody, but she liked well-worn clothes. Her jeans were a state, and she’d forgotten what colour her trainers had once been, but they were comfortable, and more importantly they were her. Lately she’d needed reminding of just who that was.

She looked at the trees. Looked at the sky. Got her mind away from her thoughts. Her thoughts weren’t kind to her. They hadn’t been for quite some time now. She looked at the twigs on the ground. They were dry. It hadn’t rained in two weeks. A rarity for an Ireland still locked in winter’s jaws. She watched a beetle scurry beneath a leaf, caught up in its own little life. To the beetle, she must be a vast, unknowable thing, a hazard to be avoided but not overly concerned about. If a god is going to step on you, it’s going to step on you. You’re not going to waste your little beetle-life worrying about something you have no control over.

She looked up, half expecting to see a giant foot descending, but the sky was blue and clear and free of gods. She waited, nonetheless.

Then she stood, and took the trail back through the trees. She used to walk this path as a child, side by side with her uncle. They talked about nature and history and family and he told her stories and she did likewise. They competed as to who had the goriest imagination, but even when he conceded defeat, with a look of mock-horror on his face, she knew he was holding back. Of course he was. Gordon was the writer of the family.

She remembered walking through this woodland with him. She could recall, quite distinctly, as if looking at a photograph, the angle at which she’d seen him. She was small and he was a grown-up, and his hair was brown and thinning where hers was long and black, but they had the same eyes, the same brown eyes, and when he laughed he had a single dimple, just like she did. It had been twelve years since Gordon had been murdered, twelve years since she’d tumbled into this twilight world of sorcerers and monsters and magic. She’d been twelve when it happened, not even a teenager when she’d started her training. The years, they had thundered by, heavy and unstoppable, a boulder rolling downhill. Bruises and broken bones and bloody knuckles and screams and laughs and tears. A lot of tears. Too many tears.

The house Gordon had left her sat on the hill, visible through the trees ahead. Even after it had officially passed into her ownership, she had been unable to think of it as anything other than Gordon’s house. Every room, and there were many, reminded her of him. Every Gothic painting on the walls, and they were plentiful, brought to mind some comment or other he had once made about it. Every brick and piece of furniture and bookcase and floorboard. It was Gordon’s house, and it would always be Gordon’s house.

Then she’d gone away. Five years she’d spent on a sprawling farm on the outskirts of a small town in Colorado. She had a dog for company, and occasionally company of the human variety, but she kept that to a minimum. She didn’t want to be alone with her thoughts, but she deserved to be. She deserved a lot of horrible things.

And then she’d come home to Ireland, and realised that in those intervening years Gordon’s house had changed, somewhere in her thoughts. Now it was just a house, and so she called it by its name, for names were important. Gordon’s house became Grimwood House, just as Stephanie Edgley had once become Valkyrie Cain.

She started up the hill, stopped halfway to turn and look beyond her land, to the farms that spread across North County Dublin like a patchwork quilt of different shades of green and yellow. Here and there the patchwork failed, replaced by neighbourhoods of new families and the roads that linked them. There was talk of a shopping mall being built on the other side of the stream that acted as a border to her property – a stream that Gordon liked to call a creek and that Valkyrie liked to call a moat. Maybe she’d get a drawbridge installed.

She climbed the rest of the hill, approaching the house from the rear. Xena saw her coming and perked up, came trotting over to greet her. With her fingers scratching the German shepherd behind the ears, Valkyrie unlocked the back door and let the dog go in ahead of her. She closed the door once she was inside. Locked it again.

Her phone was on the kitchen table. She had three missed calls. One message. She played the message. It was from her mother.

“Hey, Steph, just calling to let you know that I’m doing a roast chicken for Sunday, if you want me to make enough for you. I know it’s only Tuesday right now, but I’m planning ahead and, well, it’d be good to see you. Alice is always asking where her big sister is.” She introduced a little levity into her voice there, to pass it off as no big thing. “OK, that’s all. Give me a call when you can. We know you’re busy. Love you. And please stay safe.”

The call ended, and Valkyrie checked who the other calls were from, though she needn’t have bothered. They were both from him.

She left the phone where it was and showered, and when she came back downstairs the phone was ringing again. She answered.

“Hey,” she said.

His voice, smooth and rich, like velvet. “Good afternoon, Valkyrie. Are you busy?”

She was standing barefoot in the warm kitchen, her hair still wet and water trickling down the back of her T-shirt. “Kinda,” she said.

“Would you be able to spare some time? I could do with your help.”

She didn’t answer for a bit.

“Valkyrie?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “I don’t know if I’m ready. Give me a few weeks. In a few weeks, I’ll have myself sorted out and then I’ll be able to lend a hand.”

“I see.”

“Listen, I have to go. I’ve got things to do and I haven’t charged my phone so it’s going to die at any moment.”

“You’ll be ready in a few weeks, you say?”

She nodded to the refrigerator like it was he himself standing there. “Yep. Give me another call then and we’ll meet up.”

“I’m afraid things are a bit more urgent than that.”

She bit her lip. “How urgent?”

“Me-driving-through-your-gate-right-now urgent.”

Valkyrie went to the hall and looked out of the window, watching as the gleaming black car came up the long, long driveway. She sighed, and hung up.

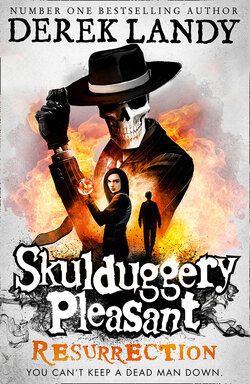

She stayed where she was for a moment, then unlocked the front door. It took a few seconds, as she had installed many new locks, and she pulled it open just as the 1954 Bentley R-Type Continental rolled to a stop outside. He got out. Tall and slim, wearing a charcoal three-piece suit, black shirt and grey tie. He didn’t feel the cold so didn’t bother with a coat. His hair was swept back from his forehead, but his hair didn’t matter. His eyes were sparkling blue, but his eyes didn’t matter. His skin was pale and unlined and clean-shaven, but his skin, that didn’t matter, either. His hands were gloved, and as he set his fedora upon his head – charcoal, like his suit, with a black hatband, like his shirt – his hair and his eyes and his skin flowed off his skull, vanishing beneath the crisp collar of his crisp shirt, and Skulduggery Pleasant, the Skeleton Detective, turned his head towards her and they looked at each other in the cold sunlight.

Valkyrie walked back into the house. Skulduggery followed.

Xena had taken up her usual spot on the couch in the living room, but when she saw Skulduggery she jumped down and ran over. He crouched, ruffling her fur, allowing her to lick his jaw.

“I always feel vaguely threatened when she does this,” he muttered, but let it continue until Valkyrie called her away. He straightened, brushing some imagined dust from his knee. “You’re looking well,” he said. “Strong.”

Valkyrie folded her arms, the fingertips of her right hand tapping gently against the edge of the tattoo that peeked out from the short sleeve of the T-shirt. “Gordon had his own personal gym installed in one of the rooms on the second floor.”

Skulduggery tilted his head. “Really? I’ve never been in there.”

“Neither had Gordon, from what I can see. The equipment was never used. It’s pretty good, though. State of the art twenty years ago. I had similar stuff in Colorado.”

“So that’s how you’re spending your time?” Skulduggery asked, walking over to the bookcases. “Lifting weights and punching bags? What about the magic? Have you been practising?”

“Just stopped for the day, actually.”

“And how’s that going?”

She hesitated. “Fine.”

“Do you have any more control over it?”

“Some.”

“You don’t sound overly enthused.”

“I’m just rusty, that’s all. And it’s not like I can ask anyone for advice. I’m the only one with this particular set of abilities.”

“The curse of the truly unique. But yes, you’re absolutely right. We don’t even know the limits to what you can do yet. If you’d like me to work with you, I’d be happy to do so.”

“Ah, I’m grand for now,” she said, watching him examine the books. “Why are you here?”

He looked round.

“Sorry,” she said quickly. “I didn’t mean to sound so … unwelcoming. You said there was trouble.”

“I did. Temper Fray has gone missing.”

“OK,” she said, and waited.

“That’s, uh, that’s the trouble I mentioned.”

“Temper’s a big boy,” Valkyrie told him. “I’m sure he knows what he’s doing.”

“Barely.”

“Well, he seemed really competent to me.”

“You met him once.”

“And during that meeting he struck me as someone you don’t have to worry about.”

“I sent him undercover. I think they might have figured out that he’s not on their side.”

Valkyrie sat beside Xena, whose ears perked up, expecting a cuddle. “I can’t do this, Skulduggery. I’m not ready to go back.”

“You’re already back,” he countered. “You made the decision to return, didn’t you?”

“I thought it’d be easier than it has been. I thought it’d be like I’d never left. But I can’t. So much has changed, and not only with me. After Devastation Day, after the Night of Knives … so many of our friends are dead and I don’t understand how things are now. I just need more time.”

Skulduggery sat in the chair opposite, elbows on his knees and hat in his hands. “You’re freezing up,” he said. “I’ve seen it happen. In war. In conflict. Soldiers see things; they do things … I don’t have to tell you about the horrors of combat, of taking lives, of people trying to take yours. With that kind of trauma, there is no easy fix. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution. You get past it however you can.

“But one thing I do know, from my own experience, is that the longer you leave it, the harder it gets. Fear is cold water rushing through your veins – if you don’t start moving, that water will turn to ice.”

“How do you even know I can still do this?” Valkyrie asked. “Physically?”

“You proved that you could when Cadaverous Gant and Jeremiah Wallow went after you.”

“That was five months ago,” she responded.

“I’m not worried about the physical,” he said. “Your instincts will come back to you. Your training will kick in.”

She looked at him, her eyes to his eye sockets. “Then what about the mental? I’ve been through a lot. Might not take much more to break me.”

“Alternatively, as you’ve been through a lot, there might not be much more that could break you,” Skulduggery said “I’m going to need you with me on this, Valkyrie. I’m a better detective with you as my partner, and I’m a better person with you as my friend. The world is a lot different to the one you walked out on. The Sanctuary system has changed, Roarhaven has changed … sorcerers have changed. There are very few people I can trust any more, and there’s something coming. Something big and something bad. I can feel it.”

“There’s always something big and something bad coming,” Valkyrie said. “Sometimes it’s you. Sometimes it’s me.”

“And sometimes you and me are the only people who can stand against it. You’re not meant to hide away here, Valkyrie. You’re not built for it. You’re built to be out there helping people, doing what you can because you don’t trust anyone else not to mess it up.”

“That was the old me. These days I can quite happily leave the big jobs to others.”

“Prove it,” Skulduggery said, getting to his feet and holding out his hand. “Come with me for twenty-four hours. If you can walk away after that, I’ll let you go and won’t ask you again until you tell me you’re ready.”

She hesitated, then sighed. “OK. But I’m not taking your hand. It’s silly and I’d feel stupid doing it.”

Skulduggery nodded. “See? You’re already making me a better person. Grab your coat, Valkyrie – Roarhaven awaits.”