Читать книгу Lady Ann - Donald Henderson Clarke - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Five

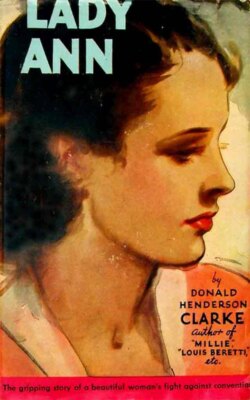

ОглавлениеAnn Steele never could have disguised herself as a boy. She had wavy brown hair which looked red in the sun, and big hazel eyes which shone with the fire of youth and health. Her forehead was sweetly moulded, her eyebrows were dark and clearly defined, and her eyelashes long. A faint powdering of freckles ran over the bridge of her nose, which was neither too small for character nor too large for beauty. Her lips were red and full, her teeth white, rather larger than the average, and her chin was well developed. Ann had a beautiful neck, round and columnar, breasts that promised plenty of food for babies and comfort for weary little heads, and a pelvis which assured babies of a comfortable entrance into life. Even at fourteen, she carried with her an intense feminine aura.

Men and boys couldn’t any more help turning and looking after her than the earth can help revolving around the sun. Old Si Brockaway, whose case of locomotor ataxia generally was credited to a wild youth, said:

“The first time I seed that filly I cried because I wasn’t young any more.”

Si was walking uncertainly, with the aid of a cane, down his front walk when Ann walked down the road barefooted. Her brown hair was blowing in the breeze and her hazel eyes were glowing in the late afternoon August sun which made highlights on her crimson lips and white teeth.

Dr. Benham, driving his old Sam in the opposite direction, waved at Si, smiled and raised his floppy yellow straw hat to Ann, and vanished up the winding road.

Si hurried faster with awkward, spraddling steps. His disease was such that he couldn’t tell where his feet were going to hit ground once he’d lifted them from it. He piped:

“Hi, Annie! Wait a minute.”

Ann stopped, smiling, and said:

“Good afternoon, Mr. Brockaway.”

Si’s gaunt face was smooth shaven. His iron-gray hair was so long that it clustered down on his neck. He wore a shirt with a stiff bosom, but no collar or coat, and his blue serge trousers, supported by white suspenders, were creased. He said:

“If I was a boy you wouldn’t be walkin’ alone, Annie.”

Ann blushed, but held her hazel eyes on his blue ones.

“I might be,” she said, mildly.

Si tossed back his head and cackled delightedly.

“By cracky,” he cried, “that’s one for you, Annie.”

Ann’s blue-and-white checked gingham dress fluttered in the breeze, which caught the fresh young scent of her and bore it to Si Brockaway’s nostrils. He crossed thin, blue-veined hands over the curved handle of his cane, polished from long use.

“A cow’s breath is sweet,” the old man said, “but the smell of a pretty young girl is sweeter.”

Ann instinctively bent her head and sniffed at herself.

“I do not smell,” she protested.

Si snorted scornfully.

“Huh!” he ejaculated. “You don’t even understand what it is to be young. There was a poet once who wrote that ‘Truth is beauty.’ He was wrong, Ann. Youth is beauty. But you don’t know it. You have to get old to know it.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Ann asserted.

“You’d say that whether you did or not because you are a female of the species, and therefore contrary,” Si Brockaway announced. “But I stick to what I said. You’ve got all your hair, and prettier than most. You’ve got all your eyesight, and all your teeth, and your digestion, and you’re sound in wind and limb, without a blemish, and there’s a sparkle in your eye that shows the sap is running strong.”

Ann looked at him doubtfully.

“What are you talking about?” she asked.

“The most beautiful sight in the world, which is a pretty young girl,” Si replied.

However, before she could make any comment on that remark, he added:

“What I really wanted to ask was if you would mind driving our cows back along with yours?”

Ann turned her head slightly to one side and looked at Si out of the corner of her eyes.

“Of course, I will, Mr. Brockaway,” she said, heartiness in her husky contralto. “I’d love to.”

“Thank you, Ann,” Si Brockaway said. “If I were younger I’d drive the cows for you.”

Ann laughed as she began to walk again.

“I believe what I see,” she said over her shoulder.

Ann stopped at the foot of the hill and picked a handful of choke cherries. Eating them, she went a few rods further to the gate of the Smith pasture. Instead of dropping the bars, she stepped up on the lower bar and swung her left leg over the top one, followed it with her right leg, and slid down into the pasture. The cows all were down at the lower end, near Big Brook. Ann had plenty of time. She moved quickly toward the brook, making quick side steps to avoid cow dung, and keeping an eye open for snakes.

Gold Tooth Billy Bangs, discharged the day before from Eastham County Jail after serving three months for vagrancy and assault, stopped still when he rounded a turn in the road and saw Ann enter the cow pasture. He caught his breath when Ann’s dress, rucked up as she slid off the bar, bared tender white skin. He slipped between the bars, and cautiously followed.

“Dis’ll make me sixt’,” he mumbled, trembling.

Ann arrived at Big Brook and walked down it a few yards until she was sheltered by pine trees which grew thick on both banks. No sun penetrated this cathedral-like solitude, where the only sound was the murmur of flowing water.

She unbuttoned her dress in the back and pulled it over her head. Her balbriggan undervest and cotton drawers followed. Cupping her breasts in her hands, she dipped a toe in the brook.

Gold Tooth Billy stood a dozen feet away, concealed partly by a rock and partly by heavy undergrowth. He watched her as she tested the water again with her toe and then stepped gingerly into it at a point where Nature had formed a pool and carpeted it with sand.

Soon she was in to her waist. Holding her breasts, she sank to her neck. The outline of her body was dimly visible through the clear water. She scooped up water in her hands and washed her face. She swam six breast strokes, when she swallowed some water, and scrambled to her feet coughing.

Billy crept closer to Ann’s clothes, wriggling slowly along on his stomach. He dropped, silent, behind a thick pine not three feet from the cheap garments. There he waited, his right hand clutching a rock.

Ann waded ashore, stepping gingerly to avoid slipping on the smooth rocks near the bank. She stood on a broad stone, which rapidly became wet from the moisture which ran down her legs in tiny streams and dripped from her arms and torso.

Billy rose cautiously to his feet and began the single step that was to take him within arm’s length of the girl. A dry twig snapped under his foot. He said:

“Christ!”

Ann whirled and dodged, with arms raised to protect her head. Billy barely missed hitting her head with the rock, which grazed her right shoulder. His shoe slipped on the wet stone, and he lost his balance. He clutched at Ann, his nails leaving deep scratches on her arm.

She pushed him away with all her young strength. The push added momentum to his falling motion, which had begun with the misstep. He pitched down the bank, his head cracking against a flat rock and snapping beneath him. He lay still.

Ann drew a long, quivering breath. A crow back in the pines cawed. A frog splashed into the pool. A cow bawled. The scratches on her arm were bleeding. An angry bruise was visible on her shoulder. She stared, fascinated, at Billy’s sprawled figure.

Then she sprang into life. She scrambled into her shirt, drawers and dress, unmindful of her damp body or her bruises. She started to run, glancing back over her shoulder. She stopped, hesitated a minute, returned to the inanimate shape and dropped on one knee beside it.

Billy’s body looked pitifully thin. His face was thin. He looked quiet and strangely inadequate lying beside the brook. His eyes, visible through slightly opened lids, were glassy.

Ann remembered her mother in her coffin, and her father in his coffin. Pictures of dead fowl, dead fish, a dead fox, and dead woodchucks went through her mind. This tramp wasn’t breathing. He was dead.

Death in itself had no horrors for Ann. It was a state into which animals you ate, or that human beings, frequently were translated. She herself, with the aid of an ax, had helped a couple of dozen chickens into this condition of permanent inanition. Death also was something that happened to other people, not to her.

She leaned over, absorbed in an unconscious study of this shell from which the motivating force had departed. He was a terrible-looking man. It was lucky for her he was dead.

Unconscious that she was performing an ancient rite, she closed Billy’s eyes, pulled his feet together, and crossed his hands on his chest.

After she had driven the cows home, and Clarence had milked them, she and Clarence ate supper in the kitchen. Rebecca was spending the day and night with her unmarried sister, Helen, and her father. Clarence drank cider which he had brought up from the cellar in a blue crockery pitcher. Ann drank milk with the cold beans and German fried potatoes, apple pie and cheese.

Clarence poured another glass of cider and took a deep drink, wiping his mustache with his fingers and sipping stray drops from the hairs. He still was in his suspenders. Conspicuous on the right strap was the star which revealed him as the town constable. The star was gold and blue enamel, and it shone in the soft light of the kerosene lamps, in brackets in the wall over the table.

Clarence watched Ann as she arose and began to carry the dishes to the iron sink connected by hand pump with a rain-water cistern in the cellar. Drinking water came from a covered well twenty feet out from the door of the kitchen. A ten-inch speckled brook trout was lord of that well. His job was to eat up insects and any other small life which might appear in the water.

Ann poured boiling water from a kettle into the dishpan. Clarence stuffed a pipe with tobacco and lighted it. There was a choking whiff of sulphur from the slow-lighting match and then a pungent odor of tobacco. Clarence sighed, arose, stretched, yawned, and said:

“Gimme a dish towel and I’ll wipe.”

“You go out and set,” Ann said. “These won’t take me a second.”

“I like to help,” Clarence said, a trifle weakly.

Ann smiled.

“Washing and wiping isn’t men’s work, Uncle Clarence,” she said.

She had heard her mother and Rebecca both say that. He put two big brown hands on her shoulders. With her hands still in the dish water, she twisted her neck and looked up at him.

“Anything botherin’ you, little girl?” he asked. “You seemed kind of quiet tonight.”

“I’m all right, Uncle Clarence,” she said.

She raised her face as if she might be expecting a kiss. Clarence petted her cheek, and said:

“If you ever should have any troubles, you tell your Uncle Clarence. Won’t you, Little One?”

She nodded, busy with the dishes. He took a muslin bag of tobacco from the shelf over the sink, filled and lighted a pipe, and stepped into the yard, Tack at his heels.

Next morning before sunrise Ann was brewing coffee and making griddle cakes and frying sausage. She made coffee by putting in one heaping tablespoonful of coffee to each cup of water, with an extra tablespoonful for the pot. Then she broke an egg, shell and all, into the grounds and mixed them up. After the mixture boiled five minutes, it was ready to drink.

She made the griddle cakes of sweet milk, adding baking soda to the flour and beating the mixture with an egg beater instead of a spoon.

“It smells good,” Clarence said, coming in from the sitting room and going to the sink.

He took an agate washbasin from the shelf, set it under the cistern pump, and moved the iron handle up and down.

“But you could have had your beauty sleep,” Clarence said. “I’d just as soon milk before I eat.”

“I like to cook,” Ann said.

Clarence picked up the basin filled with water in one hand, and a towel, a cake of yellow soap, and a comb in the other. Balancing the basin, he stepped into the woodshed, off the kitchen, where he began to splash, puff and blow.

“It’s going to rain today,” he said, drying himself vigorously.

“Breakfast is ready whenever you are,” Ann announced.

After Clarence had eaten twelve wheat cakes, a half-dozen sausages and three cups of coffee, and had lighted his pipe, Ann said:

“There’s a dead tramp down in our pasture by the brook.”

Clarence took his pipe from his mouth and stared at Ann, blue smoke oozing from his nostrils and mouth.

“A what?” he asked.

“A dead tramp,” Ann repeated.

Clarence stroked his mustache and exclaimed:

“Well, I’ll be!”

He held his blue gaze on Ann’s hazel eyes. Ann’s face was inscrutable; her eyes held a curious blank expression.

“Why in the Dickens didn’t you tell me last night?” Clarence demanded, getting up from the table.

“I don’t know,” she replied.

He pushed back his chair and arose, running his hand through his hair. He smoothed his mustache, looking at her curiously. He snorted:

“You ain’t just trying to fool me, are you, Little One?”

Ann shook her head earnestly.

“Honest I’m not,” she said. “There’s a tramp there, dead. At least, I think he is a tramp.”

Clarence bored her with his gaze. Ann smiled nervously, turned her head sidewise, and looked at him from the corner of her eyes.

“What are you staring at me like that for, Uncle Clarence?” she asked.

Clarence looked solemn and shook his head.

“Because there’s something funny about this,” he said. “I don’t understand it. It’s got me beat.”

An hour and a half later, Clarence and Dr. Benham, who also was the County Physician, approached the body of Gold Tooth Billy Bangs. They stood for a moment, silent. Clarence spat a stream of tobacco juice and said drily:

“Laid out purty, ain’t he?”

Dr. Benham nodded. He bit off the end of a fresh cigar, and then slowly extracted a pair of gold-bowed spectacles from a case and put them on.

“Give me a hand, Clarence,” he said.

He grunted as he kneeled by the body. He peered in the face, felt the head, ran expert fingers over the torso. He examined the hands. He grunted again as he arose to his feet, and coughed as he steadied himself on Clarence’s arm.

“My eyes aren’t so good, Clarence,” he said, holding out his right hand. “What do you make of that?”

Clarence took several long strands of feminine hair from the doctor. They were brown with reddish glints. Clarence raised his eyes to Dr. Benham’s.

“There’s some skin under the cadaver’s nails,” Dr. Benham added, stripping off his spectacles and restoring them to the case with hands which trembled in unison with his head. The doctor now lighted the cigar which he had been holding cold between his teeth. Clarence stood, looking down at the strands of hair.

“Annie,” Clarence said. “I thought there was something wrong.”

Dr. Benham took the cigar from his mouth with his right hand and took Clarence by the arm with his left hand.

“This tramp died of heart failure,” he said, a ghost of a grin on his lips, but his tired, wise eyes fierce. “That’s my official finding.”

Clarence twisted the lengths of hair in big, brown fingers.

“I don’t see why she didn’t tell me,” he said. “I knew something was the matter.”

“No scratches visible on her?” Dr. Benham asked.

Clarence shook his head in the negative.

“Well,” Dr. Benham continued, “then she must’ve been swimming in the brook when this tramp jumped her. She struggled, and she’s a strong, vigorous youngster, and somehow he fell and cracked his head against a rock. And it killed him. The scratches he made are covered by her clothes.”

“Then she laid him out all neat and nice,” Clarence said, “and drove the cows home and fixed supper, without saying a word. It’s beyond me.”

Dr. Benham looked up at the gray sky.

“It’s starting to rain,” he said. “Let’s get out of here.”

Dr. Benham unbuckled the case on the dashboard of his Goddard, and pulled out the storm apron, which he called a boot. Clarence helped him to snap it into place. The reins led from the doctor’s hand through a flap in the apron to the mouth of the black gelding, Tom, who alternated with old Sam in hauling Dr. Benham around the countryside.

“Might take a reef in Tom’s tail,” Dr. Benham suggested.

“Just a minute,” Clarence said.

He crawled sidewise out of the Goddard, leaned over the shaft, caught Tom’s long black tail, and put a knot in it. He was back in the Goddard within thirty seconds. He swept off moisture with a big hand.

“Teeming,” he said.

Dr. Benham chirruped to Tom, who was young and frisky and nervous to be in action, and Tom stepped off, his feet squelching in the mud and splashing in suddenly formed puddles.

Tom laid himself right into his towing job as if he loved it. His handsome head was held so high that the moderate check rein hung loose along his glistening neck. His powerful hip muscles flexed and straightened, giving an impression of living power.

The two occupants of the Goddard looked ahead at the rain-slashed road, winding between stone fences and split rail fences and dripping trees and drenched bushes, through the isinglass window in the boot. It was dry and cozy in the heavy vehicle, rumbling over the narrow road. Clarence cleared his throat. He said:

“What do you make of Annie not saying anything, Doc? Is it natural?”

The doctor kept his eyes on the road. He replied:

“It’s natural for Ann, Clarence. She comes of hard stock—those Steeles.”

“And the Smiths,” Clarence suggested.

The doctor nodded.

“I pulled three teeth for Annie,” he said, “and she never said boo, just opened her mouth and held up her face and looked at me while I used the forceps. When I vaccinated her you would’ve thought she enjoyed it.”

“She drove the cows home, same as usual,” Clarence said.

The doctor lighted a fresh cigar. He said: “Pioneer stock. Most of us around here are the same, but we’ve softened up a little. Those Smiths and Steeles and Crafts have kept right on being pioneers. If she could take the deaths of her father and mother as easy as she did, I guess she wouldn’t be the kind to worry much over a tramp.”

“That’s so,” Clarence said. “Annie inherited the old New England granite. It’s in her blood. I’m worried about her,” Clarence added. “She’s got fire along with the granite. The boys are after her already.”

Dr. Benham grunted. He said: “If she has any troubles nobody’ll ever hear her complain.”

When they went into Clarence’s house, Clarence called:

“Annie.”

Ann walked into the hall from the kitchen. She had one of Clarence’s heavy socks in her hands. She said:

“How do you do, Doctor Benham? I was just darning some of Uncle Clarence’s socks. It seems as if he pushed his toes through the ends on purpose. Will you have a cup of coffee and a doughnut?”

Dr. Benham laughed.

“You know my weakness, don’t you, Annie. I’ll have the coffee and the doughnut, thank you.”

“It’ll only take a minute,” Ann said.

Dr. Benham winked at Clarence and followed Ann into the kitchen. She was measuring ground coffee into a pot.

“I thought I’d like to put a little something on those scratches you got,” he said.

“How did you know I had scratches?” Ann asked, motionless for an instant.

“I could tell you a little bird told me,” Dr. Benham replied, “but that wouldn’t be fair. The tramp had some of your hair in his hand, and there was skin under his nails.”

Ann’s big hazel eyes were fixed on his face. She took a deep breath. Slowly her head twisted to one side, so that she was looking at him from the corner of her eyes, the gesture inherited, or acquired, from her mother.

“Now, let’s see those scratches,” Dr. Benham continued, opening his medicine bag.

“Just a minute,” Ann said, going to the pantry and returning with an egg.

She broke the egg and dropped it into the pot. Then she measured out five cups of well water from a pail by the sink and set the pot on the stove. Then she unbuttoned her dress, yellow with white dots, and slipped it over her head.

“He scratched you up good, didn’t he?” Dr. Benham said, spectacles already in place. “Wish you’d told me about this last night. Scratches and bites are better cauterized.”

He applied iodine.

“The tramp died of heart failure,” Dr. Benham said while his deft fingers of a physician touched Ann’s skin.

“He hit his head pretty hard,” Ann volunteered.

Dr. Benham grinned and his head began to shake harder.

“That might have been a contributing cause,” he admitted, “but he really died when his heart stopped beating. You can put on your dress again,” he added.

Ann swam into her dress, and Dr. Benham replaced a bottle and cotton in his bag. Then he pumped water into the basin at the sink. He said, as he washed:

“Now, if you’d cleaned the skin from that tramp’s nails, taken your hair from his fingers, and hadn’t laid him out so nice, nobody’d ever have known what did happen.”

“I’m glad he’s dead,” Ann asserted. “He was an awful man.”

Dr. Benham transferred dripping fingers from the pan to the roller towel on the wall at the left of the door leading into the dining room. Drying his hands, he said:

“I prefer that kind dead myself,” he observed, “but you should remember, Ann, that if your Uncle Clarence wasn’t the Constable and I wasn’t the County Physician, you might have had to go to court.”

“I wouldn’t care,” Ann replied. “I didn’t do anything I shouldn’t do.”

Dr. Benham patted her back.

“I don’t think you did, Annie,” he said. “Give me a kiss.”

She held up her face, and he kissed her cheek and then pinched it.

“You’re a great girl,” he said. “I wonder what’ll happen to you when you grow up.”

Ann’s face crinkled in a smile, revealing a dimple in her left cheek.

“Oh, I know,” she asserted. “I’m going to be married and have eight children.”