Читать книгу Kahlo - Gerry Souter - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

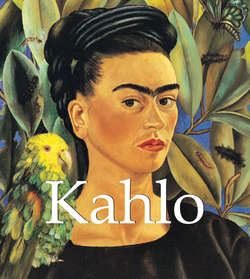

ОглавлениеThe painter and the person are one and inseparable and yet she wore many masks. With intimates, Frida dominated any room with her witty, brash commentary, her singular identification with the peasants of Mexico and yet her distance from them, her taunting of the Europeans and their posturing beneath banners: Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, Expressionists, Surrealists, Social Realists, etc. in search of money and rich patrons, or a seat in the academies.

Frida Kahlo at the age of 18

1926

Photograph of Guillermo Kahlo

And yet, as her work matured, she desired recognition for herself and those paintings once given away as keepsakes. What had begun as a pastime quickly usurped her life.

Her internal life caromed between exuberance and despair as she battled almost constant pain from injuries to her spine, back, right foot, right leg, fungal diseases, many abortions, viruses and the continuing experimental ministrations of her doctors.

Self-Portrait with Velvet Dress

1926

Oil on canvas, 79.7 × 60 cm

Bequest of Alejandro Gómez Arias

The singular consistent joy in her life was Diego Rivera, her husband. She endured his infidelities and countered with affairs of her own on three continents, consorting with both strong men and desirable women. But in the end, Diego and Frida always came back to each other.

The Accident

1926

Crayon on paper, 20 × 27 cm

Coronel Collection, Cuernavaca, Morelos

Diego stood by her at the end, as did a Mexico slow to realise the value of its treasure. Denied singular recognition by her native land until the last years of her life, Frida Kahlo’s only one-person show in Mexico opened where her life began.

Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderon was born on July 6, 1907 in Coyoacan, Mexico.

Pancho Villa and Adelita

c.1927

Oil on canvas, 65 × 45 cm

Museo del Instituto Tlaxcala de Cultura, Tlaxcala

Her mother, the former Matilde Calderon, a devout Catholic and a mestiza of mixed Indian and European lineage, held deeply conservative and religious views of a woman’s place in the world. On the other hand, Frida’s father was an artist, a photographer of some note who pushed her to think for herself. Amidst all the traditional domesticity, he fastened onto Frida as a surrogate son who would follow his steps into the creative arts.

Portrait of Miguel N. Lira

1927

Oil on canvas, 99.2 × 67.5 cm

Museo del Instituto Tlaxcala de Cultura, Tlaxcala

He became her very first mentor to set her aside from traditional roles accepted by the majority of Mexican women. She became his photographic assistant and began to learn the trade. Frida Kahlo was spoiled, indulged and impressionable. In 1922, to assure her a better than average education, she was also entered into the free National Preparatory School in San Ildefonso.

Portrait of Alicia Galant

1927

Oil on canvas, 107 × 93.5 cm

Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño, Mexico City

She devoured her new freedom from mind-numbing domestic chores and hung out with a number of cliques within the school’s social structure. She found a real sense of belonging with the Cachuchas gang of intellectual bohemians – named after the type of hat they wore. Leading this motley elitist mob was Alejandro Gomez Arias, who reiterated in countless speeches that a new enlightenment for Mexico required “optimism, sacrifice, love, joy” and bold leadership.

Portrait of My Sister Cristina

1928

Oil on wood, 99 × 81.5 cm

Collection Otto Atencio Troconis, Caracas

She remained a committed and vocal Communist for the rest of her life. The atmosphere in Mexico City was alive with political debate and danger, as volatile speakers stepped forward to challenge whatever regime claimed power only to be gunned down in the street, or absorbed into the corruption. Diaz fell to Madero who lasted 13 months until he stopped a lethal load of bullets from his general Victoriano Huerta.

Portrait of Alejandro Gómez Arias

1928

Oil on canvas, Bequest of Alejandro Gómez Arias,

Mexico City

Later, Venustiano Carranza assumed power as Huerta fled Mexico, and was no better than the lot who had preceded him. Into this vacuum were thrust the proletariat ideals of the Communist revolution that had swept Russia following the assassination of the Czar and his family in 1917. The socialist theories of Marx and Engels looked promising after the slaughter of the seemingly endless Mexican revolution.

Girl in Diaper

1929

Oil on canvas, 65.5 × 44 cm

(Portrait of Isolda Pinedo Kahlo)

Private collection

And yet, for all this progressive political dialectic and debate, Frida retained some of her mother’s Catholic teachings and developed a passionate love of all things traditionally Mexican. During this time, her father gave her a set of water colors and brushes. He often took his paints along with his camera on expeditions and assignments.

The Bus

1929

Oil on canvas, 25.8 × 55.5 cm

Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño, Mexico City

Frida became a casual student at the Preparatory School, enjoying the stimulation of her intellectual friends rather than the formal studies. During this period, she learned the minister of education had commissioned a large mural to be painted in the Preparatory School courtyard. It was titled Creation and covered 150 square meters of wall. The muralist was the Mexican artist, Diego Rivera, who had been working in Europe for the past 14 years.

Portrait of Virginia

1929

Oil on masonite, 77.3 × 60 cm

Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño, Mexico City

To Frida, the creation of the growing scene spreading its way across the blank wall was fascinating. She and some friends often sneaked into the auditorium to watch Rivera work. From a very early age, Frida had been taught by her father to appreciate the art of painting. As part of her education he encouraged her to copy popular prints and drawings of other artists.

Self-Portrait “Time Flies”

1929

Oil on masonite, 86 × 68 cm

Private collection, USA

To ease the financial situation at home, she apprenticed with the engraver Fernando Fernandez. Fernandez praised her work and gave her time to copy prints and drawings with pen and ink – as a hobby, a means of personal expression, not as “art” because she had no thought of becoming a professional artist. She considered the skills of artists such as Diego Rivera far beyond her capabilities.

Portrait of a Lady in White

c.1929

Oil on canvas, 119 × 81 cm

Private collection, Germany

And then everything changed forever. In Kahlo’s words to author, Raquel Tibol:

The buses in those days were absolutely flimsy; they had started to run and were very successful, but the streetcars were empty. I boarded the bus with Alejandro Gomez Arias and was sitting next to him on the end next to the handrail.

Moments later the bus crashed into a streetcar of the Xochimilco Line and the streetcar crushed the bus against the street corner. It was a strange crash, not violent, but dull and slow, and it injured everyone, me much more seriously…

Self-Portrait

1930

Oil on canvas, 65 × 55 cm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The scene of the accident was gruesome. The iron handrail had stabbed through her hip and emerged through her vagina. A gout of blood hemorrhaged from her wound.

Nude of Frida Kahlo

Diego Rivera, 1930

Lithography, 44 × 30 cm

Signed and dated on bottom, right hand corner: D. R.30

Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño, Mexico City

In the chaos, one bystander insisted the hand rail be removed from her. He reached down and tore it from the wound. She screamed so loud the approaching ambulance siren could not be heard.

The devastation to Frida Kahlo’s body can only be imagined, but its implications were far worse once she realized she would survive.

Portrait of Dr. Leo Eloesser

1931

Oil on masonite, 85.1 × 59.7 cm

University of California, School of Medicine, San Francisco

This vital, vivacious young girl on the brink of any number of career possibilities had been reduced to a bed-bound invalid. Only her youth and vitality saved her life. Her father’s ability to earn enough money to feed his family and pay Frida’s medical bills had diminished with the Mexican economy. This necessitated lengthening her stay in the overburdened, undermanned Red Cross hospital for a month.

Window Display in a Street in Detroit

1931

Oil on metal plate, 30.3 × 38.2 cm

Private collection

After being pinned to her bed, swathed in plaster and bandages, she was eventually allowed to go home. Gradually, her indomitable will asserted itself and she began to make decisions within the narrow view she commanded.

By December, 1925, she regained the use of her legs. One of her first painful journeys was to Mexico City.

Frida and Diego Rivera or Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera

1931

Oil on canvas, 100 × 79 cm

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Albert M. Bender Collection, bequest of Albert M. Bender, San Francisco

Shortly thereafter, she was felled by shooting pains in her back and more doctors trooped into her life. Her three undiagnosed spinal fractures were discovered and she was immediately encased in plaster once again. Trapped and immobilised after those brief days of freedom, she began realistically narrowing her options. As days of soul searching continued, she passed the time painting scenes from Coyoacan, and portraits of relatives and her friends who came to visit.

Portrait of Eva Frederick

1931

Oil on canvas, 63 × 46 cm

Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño, Mexico City

The praise her paintings elicited surprised her and she began deciding who would receive the painting before she started. She gave them away as keepsakes. With this painting, she began a remarkable lifetime series of fully realized Frida Kahlo reflections, both introspective and revealing, that examined her world from behind her own eyes and from within that crumbling patchwork of a body.

Nude of Eva Frederick

1931

Crayon on paper, 60.5 × 47 cm

Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño, Mexico

By 1928, Frida had recovered enough to set aside her orthopedic corsets and escape the narrow world of her bed to walk out of La Casa Azul once again into the social and political stew that was Mexico City. She began reexploring the heady world of Mexican art and politics. She wasted no time in hooking up with her old comrades from the various cliques at the Preparatory School. Soon, as she drifted from one circle to another, she fell in with a collection of aspiring politicians, anarchists and Communists who gravitated around the American expatriate, Tina Modotti. During the First World War and the early 1920s, many American intellectuals, artists, poets and writers fled the United States to Mexico, and later to France, search of cheap living and political idealism.

Paisaje con cactus (Landscape with Cactus)

Diego Rivera, 1931

Oil on canvas

Private collection

Study of the Portrait of Luther Burbank

1931

Crayon on paper, 29 × 21 cm

Collection of Juan Coronel Rivera, Mexico

They banded together to praise or condemn each other’s works and drafted windy manifestos while participating in one long inebriated party that lasted several years, lurching from apartment to salon to saloon and back. These expatriates fashioned a sentimental vision of the noble peasant toiling in the fields and promoted the Mexican view of life as fiestas y siestas interrupted by the occasional bloody peasant revolt and a scattering of political assassinations.

Portrait of Luther Burbank

1931

Oil on masonite, 86.5 × 61.7 cm

Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño, Mexico City

Into this tequila-fueled debating society stepped the formidable presence of Diego Rivera, the prodigal returned home from 14 years abroad and having been kicked out of Moscow. Despite his rude treatment at the hands of Stalinist art critics and the Russian government’s unveiled threats of harm if he did not leave, Diego embraced Communism as the world’s salvation.

Portrait of Lady Cristina Hastings

1931

Red chalk on paper, 47 × 29 cm

Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño, Mexico

Soon after his arrival in 1921 he sought out pro-Mexican art movements, Mexican muralists and easel painters, photographers, and writers. Within this deeply Mexicanistic society, Tina Modotti’s circle of expatriates and fellow travelers fit right in to the party circuit. Frida drifted into this stimulating circle. As Frida recalled her first meeting with her future husband:

We got to know each other at a time when everybody was packing pistols; when they felt like it, they simply shot up the street lamps in Avenida Madero.” “Diego once shot a gramophone at one of Tina’s parties. That was when I began to be interested in him although I was also afraid of him.”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Купить книгу