Читать книгу Rivera - Gerry Souter - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Discovering Europe

ОглавлениеDiego Rivera was twenty years old when he arrived aboard the steamship King Alphonse XIII in Santander, Spain on January 6th, 1907.

When Rivera arrived in Madrid, he was the sum of everything he would be for the rest of his days. His life, as the gypsies say, was written in the lines of his palm. His work ethic was brutal; his politics were as yet unformed but inclined toward the lowest level in the trickle-down economy in which his father had been broken by the bosses. His art had no direction, but he was also an empty vessel anxiously waiting to be filled.

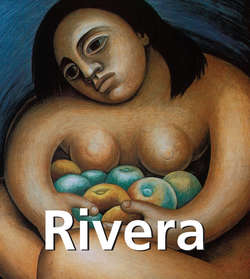

Study for “The Jug”

1912

Gouache on paper, 28.5 × 23 cm

María Rodríguez de Reyero Collection, New York

Diego was ready to learn about women, but he already possessed sensitivity, a gentle nature and an ability to lie with great sincerity as he created stories that would become the myths of his life. He would always have women.

The next day, he presented himself at the studio of one of Madrid’s premier portrait painters, Eduardo Chicharro y Agüera. Diego proffered his letter of introduction from Dr Atl and was led to a corner of the studio he could call his own. The other students scrutinised the fat Mexican farm boy and were unimpressed. A heady perfume of paint and turpentine, open tins of linseed oil, raw canvas and pine wood for stretchers filled the room, and he set to work at once. He painted for days, arriving early and leaving late. Gradually, with his sheer brute concentration and resolve, the value of his stock rose among his fellow classmates and he became part of their social circle. And, here in Madrid, an interesting quirk of content appeared amidst his self-generated themes. No religious paintings by young Diego have ever been recovered or noted. Holy scenes from the Bible were big sellers and the more slickly rendered the better. Diego, however, who had bad memories of the Church, and of his father’s anti-clerical teaching and writing, eschewed the gaudy morality plays of Madrid’s commercial painters. He continued as he was, a young Mexican man living off a free ride and working hard to find his own vision and style.

Adoration of the Virgin

1912–1913

Oil and encaustic on canvas, 150 × 120 cm

María Rodríguez de Reyero Collection, New York

Portrait of the Painter Zinoviev

1913

Oil on canvas, 97.5 × 79 cm

Private collection

Diego’s brush with the Madrid avant-garde found him embroiled in an anti-modern art movement (el Museísmo) which demanded the abandonment of modern art for the 300-year-old El Greco paintings. This move was hardly a plunge into the future, and Rivera’s painting from his isolated two years in Spain was conventional, slick and bland.

While Picasso was creating the revolutionary Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Rivera ground out The Forge, The Old Stone and New Flowers and The Fishing Boat. The paintings were handsome if only because of their superb technique, but they would also have looked at home in any mercado tourist shop.

Woman at Well

1913

Oil on canvas

Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico City

The bohemian lifestyle eventually laid Diego low, so he stopped drinking and went on a vegetarian diet. He took hikes and began reading very serious books: Aldous Huxley, Emile Zola, Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche, Charles Darwin, Voltaire and Karl Marx. He devoured books on mathematics, biology and history, drowning his over-indulged body with intellectual stimulation.

After sticking it out for two years, Rivera, apparently flush with winnings gathered from a Spanish casino, took a train to Paris. No sooner had Diego put down his bags than he was out the door, down the hill and across the Seine heading for the Louvre.

Still Life

1913

Oil on canvas, 84 × 65 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

The Paris art scene must have overwhelmed him. In the two months he spent in the city, very little time was wasted as he got out his paints and brushes, joining other Paris-struck painters on the banks of the Seine. He wandered through the galleries peering at the works of Pissarro, Monet, Daumier and Courbet. Gallery and museum walls glowed with colour and ways of seeing and techniques so foreign to his well-ordered provincial realism.

However, his feverish absorption of French art had to be shelved for much of June as he ended up on his back, sick with chronic hepatitis, a malady that would return again throughout his life. The illness did give him time to plan a trip to Brussels. Enrique Friedmann, a Mexican-German painter, accompanied him.

The Eiffel Tower

1914

Oil on canvas, 115 × 92 cm

Private collection

As summer settled over Europe, Rivera and Friedmann travelled from the Brussels museums of Flemish masters to the small city of Bruges, thought by many to be the home of Symbolism. While there, he began the painting House on the Bridge, one of many paintings he completed in Bruges, rising at dawn and painting until the light was gone. This introspection mirrors his early Mexican landscapes and picks up his feelings of being the observer, the outsider looking in, seeing through his gift of artistic translation.

Portrait of Kawashima and Fujita

1914

Oil and collage on canvas, 78.5 × 74 cm

Private collection

One day, while living on the cheap, Rivera and Friedmann wandered into a Bruges café to grab a bite before catching some sleep in the railway station waiting room as though they were waiting for the next train. A sign outside the café offered “Rooms for Travellers”. Hoping for a good deal they entered and took a table, a brioche and two coffees. Rivera was eating when he looked up and discovered María Blanchard, his girlfriend from Spain, grinning at him from the café’s doorway. He stood and held his arms wide. Next to her stood a “…slender blonde young Russian painter…” named Angelina Beloff.

Zapatista Landscape (The Guerrilla)

1915

Oil on canvas, 144 × 123 cm

Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City

After a period in London, the then inseparable four returned to Paris, where Diego finished the House on the Bridge begun in Bruges and started a new painting, Le Pont de la Tournelle, in which he transposed the remembered London mist with its unique pinks and greys to the banks of the Seine. This painting shows workers unloading wine barrels from a barge onto the quay. To Rivera it represented a first look at what was emerging as his own style and it signalled the arrival of his empathy for the toil of the worker. He credited this new class sensitivity to his relationship with Angelina Beloff and the writings of Karl Marx.

Portrait of Martín Luís Guzmán

1915

Oil on canvas, 72.3 × 59.3 cm

Fundación Cultural Televisa, Mexico City

The Salon des Indépendants accepted six of his paintings: four Bruges landscapes, La Maison sur le Pont and Le Pont de la Tournelle.

He had reached a point in his technique where he could paint in any manner he chose, paint like any artist he chose; any artist but himself. He had been abroad for four years and while he had grown considerably into his twenty-four years, he was still homesick.

Portrait of a Woman, Mrs. Zetlin

1916

Gouache on paper, 16 × 13 cm

Claude and Pierre Ferrand-Eynard Collection, Paris