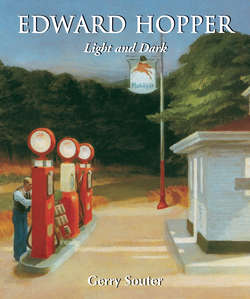

Читать книгу Edward Hopper. Light and Dark - Gerry Souter - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеThe man’s the work. Something doesn’t come out of nothing.

– Edward Hopper

“If you don’t know the kind of person I am

And I don’t know the kind of person you are

A pattern that others made may prevail in the world

And following the wrong god home we may miss our star.”

Excerpt: A Ritual to Read to Each Other

– William Edgar Stafford, 1914–1993

1. Self-Portrait, 1903–1906. Oil on canvas, 65.8 × 55.8 cm. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Josephine N. Hopper Bequest.

Edward Hopper’s realist creations in oil, watercolour and etchings earned him a degree of celebrity throughout America’s interwar years from the 1920s to the 1940s. During the last twenty years of his life, the honours came, the medals, the retrospective exhibitions and the invitations to countless museum and gallery openings, many of which he turned down. He was a recluse, a captive of his overachieving upbringing, a prisoner of humiliating memories of early rejection, the tenant of his failing body and the sole occupant of a darkly silent philosophy that resonated with virtually anyone who confronted his work. Hopper’s creative efforts discovered elements of the American scene that appear to be silent remnants left behind, or events about to happen. His work is his autobiography.

Edward Hopper and his wife, Josephine – in later years almost nobody thought of him without her and so they are linked in art history – were married for forty-three years. He stood six foot five inches and she topped out at five foot one inch with coppery red hair. Virtually everything in their life together orbited around his art. Josephine Nivison Hopper also had modest talent as an artist. Through her contacts, she helped him exhibit his first watercolours. Nevertheless, in Hopper’s solar system there was room for only one artist – himself, the sun at its centre. Yet she insinuated herself into his self-absorbed world. Once they were married, with few exceptions, the only women appearing in Hopper’s small repertory company were painted from Jo’s nude or costumed form.

Besides modelling, in 1933 she began a relentlessly personal diary of their life together adding to a detailed record book of his work: its size, brand of paint used, canvas or paper, oil or watercolour, what gallery accepted it, and its selling price – less 33 % gallery commission. With her own art career in tatters beneath the weight of his creative shadow and callous indifference, she bonded with him as clerk, diarist, house lackey, social prod, financial juggler and creative scold.

Drip, drip, drip, her constant flow of chatty encouragement wore down the resolve of his blockages, his inability to work, his cavernous depressions. She also knew how to push his buttons and twist the guilt knife. He saw no reason to stop reminding her of her second-class status in the household and as an artist. They splashed each other’s psychological vitals with acidic scorn and calculated goading and then battered each other, drawing blood physically and emotionally. But their mutual dependence persisted.

Edward and Jo also had good times as they explored the eastern Seaboard beginning in the 1920s, stopping to sketch and splash on watercolour. They made friends of the people whose homes and boats and special places Edward drew and painted. They tramped together along the streets of New York where they had studied art and were part of the Greenwich Village artist scene.

From the 1920s to the 1960s they both embraced the realist American art movement as other painters and sculptors came and went. Hopper stood like a rock amid the chaos that welcomed, then rejected the Impressionists, dismissed, then lionised the Expressionists, Surrealists and other “ists” that bubbled to the surface. His work needed no manifesto, belonged to no school. A Hopper needed no signature and its value never dropped. Like bankable Alexander Calder and Pablo Picasso, once he hit his own creative personal stride his paintings and etchings always found buyers. Hopper’s two-dimensional world turned in on itself from unpopulated introspective compositions of hills, boats and houses to include a pensive collection of seeming allegories featuring a silent cast of drained characters, each captured with something yet undone, or done and now buried beneath regret, or just waiting to see what might come and change their lives.

From his birth in Nyack, New York in 1882, to his death at the age of eighty-five sitting in his chair in the New York City apartment-studio he occupied for fifty years, Hopper spent his eight decades in pursuit of light and shadow. He mastered executing their delineation of our lives and environment. Thanks to Josephine, his would-be browbeaten Pepys, busy, busy, busy beside him, we have a small and often vitriol-spattered window into his reclusive world. The pursuit is a rich journey through painful creative self-discovery and massive self-denial. We travel through the evolution of technical facility in a schizophrenic labyrinth snaking between commercial and artistic success fuelled by the need for recognition, underscored with self-loathing and ending in his lifetime among the immortals of fine art.

Many writers have taken this trip and for their discoveries and their scholarship, I am grateful. To the museums and institutions that hang his work and archive the papers accumulated by his long life goes more of my gratitude. I also owe much to my years as a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago where, brush in hand, I fought the lonely battle with my own demons. Every day I walked through the galleries on the way to my classes. Every day I walked past Hopper’s Nighthawks and every day, when my mind wasn’t occupied with the detritus of youth, I felt success as a painter slipping away. Only later I discovered that art is supposed to be painful if you do it right. Following Hopper’s tortuous career prickles long dormant memories.

Each writer has come away with a slightly different Edward Hopper. Even though his paths are known, his acquaintances documented, his days and dates authenticated and his body of work is catalogued, what emerges is still an enigma. Hopper the man and artist remains a puzzle box with many hidden compartments and sliding panels. Located within the final secret space may lie a Rosetta Stone, a “Rosebud,” a key to his workings. Since the only paths to the “why” of a creative artist lie in the trace elements left behind and what the artist chose to reveal, these scattered traces and choices cause curious writers to put on comfortable shoes and begin.

– Gerry Souter,

Arlington Heights, Illinois

“No one can correctly forecast the direction that painting will take in the next few years, but to me at least there seems to be a revulsion against the invention of arbitrary and stylised design. There will be, I think, an attempt to grasp again the surprise and accidents of nature, and a more intimate and sympathetic study of its moods, together with a renewed wonder and humility on the part of such as are still capable of these basic reactions.”[1]

– Edward Hopper, 1933,

Notes on Painting (excerpt)

2. Jo Painting, 1936. Oil on canvas, 46.3 × 41.3 cm. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Josephine N. Hopper Bequest.

1

Edward Hopper, Notes on Painting, “Edward Hopper Retrospective Exhibition”, catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, 1933, courtesy: Frances Mulhall Achilles Library, Whitney Museum of American Art