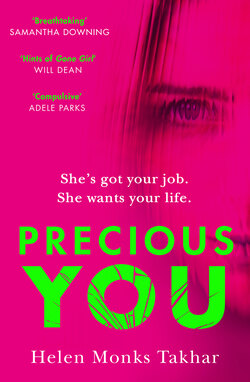

Читать книгу Precious You - Helen Monks Takhar - Страница 15

Chapter 3

ОглавлениеKatherine

This is how catastrophic change begins. Small disturbances at the surface, the first suggestion of the sinkhole opening beneath; the moment in the horror movie the protagonist sees something out of the corner of her eye and dismisses it witlessly. I used to love horror movies. I can’t bear them now.

Even though I felt uneasy about you, I couldn’t wait to see you that second morning. I couldn’t give what I felt a name. I still can’t. The best I can do is say it felt like a kind of imprinting. I’d been let down by my life and orphaned by my friends. I hadn’t talked properly to anyone who wasn’t my partner in so long, it was as if I had an overflowing store of friendship backed-up in me. You. Yes, Lily, even though I wasn’t sure about you, I was that pathetic; I was ready to bury my doubts. This is who you become when no one returns your calls, and the only people troubling your mobile are your GP, your partner, or Vodafone.

On Tuesday morning I spent ages choosing an outfit that might make me look fresh and relevant and not mutton dressed as lamb. I hopelessly tried to do my makeup to achieve a dewy sheen. I wondered if the time was coming when I should let my natural colour come through, or dye my hair something other than black, which seemed suddenly blocky and incongruous against my dulling face. I desperately wanted to collapse the years between someone like you and someone like me.

Part of me was glad when you weren’t at the bus stop. I was disturbed by the horrid dream I was struggling to shake off, but buoyed by the fact my articles would be live on the website and in the shiny new editions on everyone’s desks by the time I got in. You may have changed the cover for the issues they’d distribute at the awards, but this edition would be all mine.

I got to my desk. Still no you. And no coffee from Asif either. I turned to find the two of you nestled next to each other on the old sub editors’ desks, huddled around what looked like proofs of the most recent issue.

‘Good morning. Time for a quick catch up? Katherine?’ Gemma tried to get my attention from the doorway of her office.

‘Be right there,’ I said distractedly, watching Asif run his fingers over his beard as you looked to gauge his reaction to something you’d just said. I watched until I couldn’t anymore, closing Gemma’s office door slowly on the sight of you throwing your head back in glee. Asif looked as if he could just climb right inside you there and then.

‘Congratulations on this.’ She threw a fresh copy of Leadership towards me over her desk. ‘Some great foundations we can really build on.’

‘Thank you.’ Is that it? For 12,000 words from your most senior writer? Patronising.

‘What I want to talk to you about, today, is how we’re going to achieve that.’

‘Yes?’

‘I hope you’ll take what I’m about to say in the spirit in which it is intended … I’d like us to talk about reorganizing our content, making a few tweaks to your writing. So, to that end, I’ve asked Lily to look at what’s working and not working on the website. I should probably tell you, early indications on the two articles she posted—’

‘Two articles? I didn’t see any copy from her.’

‘Asif edited them yesterday evening. Well, they’ve already had more click-throughs and longer combined viewing times than all of your content in the last four weeks put together.’ I watched you through the glass. You were now flicking your fingernails under your chin, before biting your bottom lip as you started to type. I was ready to assume it was your picture byline driving your traffic. ‘She’s young, but she’s a quick learner and she knows how to give online readers in particular what they want, so I’ve booked some time away from the office for you and her. She’s going to help you look again at your writing. There’s no shame in needing to re-boot. You could find this is the best thing to happen at this stage of your career. Details to follow. Now, are you up for the challenge?’

What a slap in the face. The humiliation. You were going to teach me. I didn’t yet know you would teach me the lesson of my life.

I had no choice but to say, ‘Of course I’m up for it.’

You kept trying to talk to me all day, but I gave you the brush off. I needed more of an idea of what I was dealing with before I let you know anything else about me.

I read your pieces. A horrifying truth dawned. You were actually pretty good at this. A natural attention-grabber. Your headlines were nearly as enticing as your picture byline; your copy was as taut as mine was saggy. When I re-read my features, they felt in the reading how they’d felt in the writing: hard work. I was angry, I thought it was at you and Gemma, but it was really at me, for being so tired of it all.

But what had Asif been thinking, putting up two pieces from a day-old intern like that? He sent the odd smile over from his side, but knew me well enough to give me some space. It wasn’t until gone seven when the office had emptied that I heard him come up behind me to say goodnight.

I looked about. You weren’t at your desk, but your machine was still on, so if you were going to file any more sparkling ‘content’, it would have to go through me.

‘Late night at the office, K? Kind of reminds me of old times.’ Asif, hands in his pockets, took a step closer. I guessed he was trying to get back into my good books and it was only to make him feel better that I told him, ‘Ah, the days of yore. I miss them too. But you know me, Mr Khan, there will always be a part of me that’s down with the brown.’ I smiled and turned in my seat to face him.

And I don’t know how, but there you were, right behind him; a millennial spectre clutching an orange Bobble water bottle, complete with a luminous shard of cucumber glowing within. You looked flustered, maybe because you were appalled at the idea of Asif’s buff twenty-six-year-old body against my creaking bones as they had been once. I noted to one day tell you that just because you’d turned his head, you couldn’t undo history. Not even you.

‘Sorry, I thought I’d get a head start transcribing my—I can’t concentrate in my flat.’ You turned to Asif who was by then smirking at his shoes.

‘Don’t worry. I’m off. I’ll bid you ladies goodnight. Don’t work too hard.’

We both started typing and a difficult silence settled.

‘Would you like me to pretend I didn’t hear that?’ you said eventually.

When did young people get so prissy, so unable to take, give, or hear flirting? I had seen this attitude in so many of my interns in recent years. The rebuffed compliment, the blatant distaste when I’ve said something, anything, even faintly sexual. This wasn’t the first time I’d wondered exactly when and why a whole generation became so joyless, so sexless. Then I wondered if your indignation was fired because you’d heard I had a serious partner and believed there was only one way to do that right.

A pause.

‘Shall I tell you something? My partner and I have a code,’ I began. I wanted to shock you now, I had you on the ropes and this would be my one-two jab, to show you up for the wrong-headed innocent you were, give you something else to chew on. ‘There are rules. I meet someone I’d like to have sex with, we discuss our feelings and he signs it off, or he doesn’t. If he comes across someone he’d like to have sex with, I say yes, or I say no. My partner signed off on Asif, once or twice, but then we agreed I should stop. You see, we’re a couple who are first and foremost for each other. That never changes. But if we’re lucky, Lily, we’re a long time alive, and a long time together. People my age are capable of believing there’s more than one way of doing something. My advice to you? Don’t judge what you haven’t tried.’

Suddenly, displaying the full peacock tail of my sexuality, I felt restored; the real me rising from the ashes of the day. But this wasn’t my one-two jab, it was your rope-a-dope: the art of taking blows, letting the other fighter expend themselves before going in for the kill.

‘I wasn’t talking about that, whatever you’re talking about.’ Your face was flushed with righteousness. ‘Racist language in the workplace? It’s a sackable offence.’

You should be careful. How right Iain had been.

And in that moment, I thought I knew what you were. You were here to get me sacked. Plain and simple. Gemma could be the acceptable face of sisters sticking together, middle-aged women doing it for ourselves, but you, her, the faceless head honchos now making up the new board, you all wanted me out.

If only it had just been this.

‘I don’t think I understand, Lily? Exactly what racist language did I use?’

‘I, literally, don’t even want to say it out loud.’

‘Say what?’

‘That racist phrase you just said to Asif.’

‘You have to be kidding.’

You began typing again in silence.

‘Language, between friends, old friends. It’s complicated. Nuanced. Coded. Sometimes, Lily, it’s perfectly possible you might not understand what you’re actually hearing.’

You took a sip of your cucumber water then typed some more. I started to pack my bag as if I was leaving work as normal, trying to act like someone who was definitely not at any risk of being sacked for being racist.

‘There’s a code of conduct?’ you said eventually, voice sweeping up at the end.

‘What, so, we can all work in a “safe space”? There’s a lot more to feeling safe at work than bleeding the joy out of every exchange between grown adults. Trust me.’

A pause.

‘I guess I heard about your time off. I just thought you might need to possibly be a bit more careful?’

‘I wasn’t on holiday. And I was led to believe confidentiality was enshrined in the new Code of Conduct.’

‘I’m sorry. I must have heard Asif or one of the interns say something.’ You tucked your hair behind your ears and looked back at your screen before deciding to power down. I logged off too, watching for a second as the light drained away from my machine, mesmerised by the little white dot in front of me, feeling the exhaustion in my bones, my brain. A sensation rushed in around me with sickening familiarity: the compulsion to lie down and never get up again. I didn’t even notice you’d come to stand by my chair, so when I turned to leave, your body blocked my path. I gasped. Awake again.

‘Katherine. Would you consider going for a drink with me? Tonight? Now? Give me a chance to clear the air? I’m sorry, I think I’ve really overstepped the mark. I’m still feeling my way with this place. With Gem.’

Your black eyes seemed to plead with me. And I thought I saw it again, that loneliness. Your need to connect with another person. Perhaps we would end up getting a burger and talking like we’d known each other forever after all?

‘Alright. OK,’ I said, nodding dumbly, taken aback by the glint of a feeling shared.

You handed me my leather from the nearby coat stand.

‘Shall we?’ you said, smiling.

‘Give me one second.’

I nipped to the loo to text Iain:

Snowflake wants to go for a drink. Don’t worry about dinner. See you later xx

I couldn’t remember the last time I’d sent a ‘Going for a drink, be home late’ text over some spontaneous invitation, maybe one of the girls finding themselves on the Southbank or London Bridge and thinking Sod it, let’s see if Rossy’s up for a drink. Iain knew how good it would have felt for me to be able to say I wasn’t coming home yet. He texted back:

That’s fab. Enjoy xxxx

You and I left the office, and that’s when we really started to talk.

I don’t think I’ve ever really seen you laugh, but you’re very beautiful when you smile. I remember thinking that you smiled a lot that night and how good that made me feel about myself. You were enjoying my company, my stories. You weren’t watching the clock, not like my old mates towards the end. And unlike them, with you, there was no sense of you waiting for the moment when you might, in not so many words, suggest I ‘pull myself together,’ or inevitably get to asking if there was any way whatsoever it would be possible to get some money back after The Film. Talking without these things hanging over the conversation made me feel more like me again. And you asked so many questions that let me hear something of my old voice again. You knew how we all love a great listener, didn’t you?

Looking back, I can see there was a tinge of something pre-rehearsed about some of your questions, and somewhere I clocked you’d all but had a personality transplant since your almost total indifference to me in the cab on Monday. But I jumped clean over my doubts and right into telling you my life story.

Chatting to another woman again about my career, my reflections on life so far, was like slipping into a warm bath. How I wanted to soak away the aches and the pains of the last few years. The imprinting process in full swing as I tried to forget all the friends who’d abandoned me. First, the ones who had babies left me, though I could understand why. I was terrible around children. Who would want the scary lady in the leather jacket who never smiled near their kids? Then, The Film did for some of the women I’d cared about most. That hurt, a specific pain I’d not known before. I suppose it was like being dumped, but I didn’t know because I’d never been dumped. My luck had run clean out. My girls, my main girls were ‘pressing pause’ on me, that’s what they said. But they never came back. Finally, there were a couple of remaining second circle friends who hadn’t invested in The Film. But they didn’t know what to do with me when the beige began to blow in. They left me too. Soon enough, the only things left standing were my work and my Iain.

‘So, where did it all start for you, being a journalist? I’d love to know. I’m so early in my journey, I know how much I need to learn!’

‘Well, I came down to London late nineties, worked in a pub for a bit, this was in the days when you could rent a room in Walthamstow for forty quid a week. I know, fucking ridiculous, right? I applied for work experience at every local paper all over London, but with no training, no degree and no connections, no one would look at me. Then one night, I was out seeing some mates in Islington and I saw these two guys start on some bloke. They had baseball bats. It was … ugly. My mates ran off home, fair enough, but I watched from across the way, got out my notepad and started getting down the details. Someone called the police and an ambulance. I managed to get some other eyewitness quotes and something from the police too. I told them and everyone else I was a reporter from the Islington Gazette. Then, I scooted back up the Victoria Line to my room, begged one of my housemates to borrow his PC, and filed the story to the Gazette. Just 250 words, but it was enough to persuade them I could come and do work experience. Pretty cool, eh?’

‘My god, yes! Amazing! Then what?’

‘I got there, loved it, worked my tits off, got on staff. The money was shit though. I knew I’d earn more on a trade mag. Junior news and features writer on Leadership was the first thing I applied for.’

‘And you got it.’

‘And I got it.’

‘And quickly became indispensable, then the youngest editor in the title’s history.’

‘Yes … Yes, that’s me. How did you—’

‘I’ve been proofing biographies for the awards supplement?’

I nodded. It sounded feasible.

‘I want you to know, I have, like, so much respect for your experience and how you’ve come up the ranks. It’s inspiring. I also really want you to know, I’m so embarrassed about the Gem-making-us-do-copy-camp-thing. I basically begged her not to make us do it. But she’s got her “own ideas” about how she’s going to run things, even though she has basically zero experience in journalism. But who are we to talk her down?’

We.

I liked how that sounded, so much. Too much. It resonated around my loneliness, arousing something deep and dormant. You and me: friends. The cub reporter and the grizzled editor, an alliance across generations against ‘the man’, or woman, in this case.

‘Don’t worry about it. I’m sure it’ll be fine,’ I said, swallowing the end of my second gin.

‘But I really do. I’m such a worry-wort. Are you a worrier? Sorry, I’m not talking about, you know, your time off or anything.’

‘My beige period?’ I tried to laugh.

‘Could I ask … was there a trigger for what happened to you?’

I sighed and looked at you side on, my head cocked to show you I was trying to decide whether to share my private thoughts with you or not. But at that point, it was just that: a show. The sad fact was, I was dying to tell you everything about me. While I was still, apparently, thinking about it, you added, ‘You don’t need to worry about me. You can trust me.’ And I wanted to believe you. I wanted to forget about the taxi ride and your holding back the truth about how you came to my magazine. I wanted to put all that to one side, chalk it up to coincidences and let myself believe the only thing for me to worry about was my failing talent. I wanted to let you convince me this was the case and at times like those, you were so dreadfully convincing.

‘I’m not worried about you.’ Probably the greatest lie I told myself about you, worse than convincing myself you were a friend-in-waiting.

‘Because I think you’ll find I could be very good for you. If you give me a chance.’

And your smile shone at me again as you moved one hand out across the table in my direction, reminding me of my young self again, that combination of steel and softness.

It’s then I saw it clearly: I could mentor you. We could go through the whole copy camp charade, but I’d bring you round to my way of doing things, share with you everything I knew. I would mentor you and in return you could teach me the ways of your digital world. We’d be unstoppable. We’d propel the magazine and website into the stratosphere. More readers, more advertisers, more sponsors, more everything. I would initiate our partnership by conceding to your absurd millennial vocabulary.

‘Triggers for my illness … Well, I would say it wasn’t just one thing and I’m not sure I wholly believe in triggers, not for me anyway. I’d had hard times before and they hadn’t got me down, not down-down. If anything, the dark days got me up, off my feet. Then when I got ill, it was just … total. I felt flattened, the world didn’t look like the world anymore. It’s hard to explain, but I don’t think it was just a case of, “Oh my god, we’re broke,” or “Oh my god, am I really celebrating my fortieth birthday at Leadership?” or any one thing that pushed me over the edge. It was nothing and everything.’ I shrugged, as if I was talking about some mysterious thing that had happened to me a very long time ago. You changed tack.

‘Wow. So from the late nineties to now, that’s like, a whole bunch of time. Leadership must be like a home-away-from-home.’

‘It is, or it was, before everything changed.’

‘Maybe it can be again?’ you said softly and I had to look away so you couldn’t see how much you’d moved me.

‘Sometimes I … I feel as if I’ve let Leadership down. I’ve let myself down. I know we’re going to be OK; I know we can survive using a rolling buffet of interns to keep the lights on and sponsored content to pay me.’ You visibly bristled at this, I ignored it. ‘But I can still see it, we’re slipping behind editorially. Readers, they’re so fickle these days. I’ve seen the data. They skip through a story that took a week to put together for the magazine in fifteen fucking seconds on the website and I don’t know why. You know, I did see the digital revolution coming? I thought I could ignore it, but it got bigger and bigger, so much bigger than I thought it ever would, until it changed fucking everything and it feels like I don’t get anything anymore.’ I saw some bubbles of spit land on my sleeve on the ‘m’ of ‘more’. I was literally, as you would say (correctly for once), frothing at the mouth. ‘Sorry. I—’ I began and you rubbed my forearm. ‘I don’t usually spill my guts like this.’

‘Well, get used to it, boss. OK? Shall we get a bottle of something red and warming?’

‘Yes! Allow me. Fuck it all, right?’

I noticed you recoiled slightly whenever I swore. I suppose I naturally swear a lot, but I’d always thought most journalists were prone to sweariness, whatever their age. As much as I believe people like you need to toughen-up, I didn’t like the faint tell as the skin under your eyes tightened at each curse. Before too long into our night, I stopped the ‘fucks’ and ‘cunts’ and even the ‘arseholes’. I started to feel less angry in doing so. You helped me soothe myself. Maybe you millennials were actually onto something.

It began to feel, as we sat there in the corner of The George that night, when tourists and beery workmates came and went around us unnoticed, that you and I were really communicating. I felt the warmth of a couple of gins and a bottle of Rioja and the full flush of releasing all the conversation I had pent up in me. And it was thrilling to observe your pristine complexion up-close, the swell of your cheeks, the way you tapped the white triangle of skin above your tangerine v-neck from time to time. My skin once glowed like yours.

We both looked at our glasses, only a drip in each of them. You poured the remainder of the bottle into my glass. I sensed our evening drawing to a close. I didn’t want it over yet.

‘Writing was a real escape for me. Not just journalism, writing my own stuff too. I wrote my first manuscript, just for me, to get my head together about … childhood stuff, I suppose. Does your blog help you get your head straight?’

‘I guess. That and my diary. I try to work out my future by processing the past and reporting on the present there.’

‘I used to keep my notepad with me at all times in case I ran into a story, but also if I had a thought about something or other I wanted to get down. Iain used to call it my “little book of lottery tickets”. One of them had the winning line on it, the one that would help me write the next manuscript. The One. The one that would save me, get me out of Leadership and put my life where it deserved to be …’

‘Wow. It sounds like, what did you say your husband’s called again, Iain? He sounds super-supportive.’

‘Iain. My partner, not my husband.’

You’d invited him into the conversation and then I really let myself go, encouraging you to excavate me, draw things to the surface. Because when I spoke about Iain, it felt so good to share all the gestures, big and small, that made him so wonderful. When our relationship seemed of interest to you, he and I became my proudest achievement. I seemed to be educating you about proper, grown-up partnerships. You asked me more and more questions.

‘How did you know Iain was right for you?’

‘I suppose I fell for him, hard. I sort of realised when I met him, I thought I’d been walking forward into my life. I mean, I had, but I’d been limping on one leg, because now I felt complete, balanced, a left leg to the right.’

And then I started telling you how Iain and I had come to sleep with other people, figuring I could educate you about the world, how things could be. ‘We were at a party and I had this thought that we shouldn’t deny ourselves, even though we knew we were going to be together for a long time, maybe forever. He knew exactly what I meant. That’s why we work, Lily. We have rules, like I said. We talked about everyone before and after.’

‘Who were the other guys you were with?’

‘God, all sorts really. Contacts. Friends. Friends of friends. A good many colleagues. Interns. Lots of interns.’ I immediately regretted saying this as your face twitched when I said ‘interns’ and I instantly tried to cover my tracks. In truth, there had been fewer takers over recent years, which couldn’t have helped me much. It suggested either that I wasn’t as attractive as I was when I was younger and/or most of the millennial generation were as ridiculously puritanical about sex in the workplace as I suspected. It’s hard to say which I found intuitively more disappointing. ‘I mean, yes, interns, but not for a while. Mostly when I was closer to their age. The thing with Asif? We have a bit more of a connection than interns from back in the day. He’s like my work-husband. We don’t play that way anymore, by the way. My idea.’

‘Sure,’ you nodded, giving nothing away. ‘So, what’s Iain’s type?’

‘Well, he doesn’t do wallflowers. He likes the firecrackers. Women who aren’t backwards in coming forwards, if you know what I mean.’

I liked talking about the women of yesteryear, who I really was and how I played things before living made me sick. It was all so amazingly sexy then. Until it wasn’t. Until it started to feel like an effort, like every other plate I had to keep spinning in my life. Even before I got properly ill, I’d barely looked at another man for months. Iain had calmed right down too. We’d fallen into a slower rhythm. Gone was the bed-hopping high summer, and in came a calmer September which risked heading to the freezing dead of winter if I wasn’t careful. And I wasn’t careful enough in the end, because of you.

‘What about you? Is there anyone special in your life?’

‘No, not at the moment. Hey, I’d love to meet Iain one day.’

And I let you leave it there. Because I immediately had an image of the three of us together: sat around a table, wine and conversation flying between us. We’d laugh; I’d catch Iain’s eye and he’d send me a smile that told me he was glad I’d met you, happy I had someone new to share my thoughts with, enlivened by the idea you’d be good for me, and therefore, for both of us.

‘What are you doing this weekend? Why don’t the three of us have lunch?’

‘Hey, that’d be perfect.’

We swapped numbers.

You made me take a selfie with you. It felt stupid and foreign, holding my phone on high in an unpractised way. You corrected the angle of my arm at first, your thin fingers grasping the muscles on the inside of my upper arm. I could smell all of you.

‘No, higher up. You never done this before?’

‘Erm, yeah, not as much as you lot …’ Then, in friendly frustration, you took my phone off me before scrunching into my side and miraculously working out how to put on the flash and some kind of flattering filter before handing my phone back. I loved how good we both looked in that picture. How close. In age. In comradery. In friendship. You were giving me a direct line to who I used to be: young and fun, someone you would fight to be friends with, not avoid.

I’ve looked at that picture you took of us a million times. It was far enough away that you can’t see my pissed redness, my dark circles, my desperation. Nor could I see the black energy hiding behind your eyes. Like our selfie, I vowed that at our planned Sunday lunch with Iain you would see the very best of me again.

It got to chucking-out time and you said you needed to get your bike from the yard behind the office. As we started to leave, I was overwhelmed by the idea of hugging you. I felt like we’d breached something, moved somewhere together. I stood up woozily. I remember you holding my forearm to steady me and that somehow becoming a prolonged embrace. I could feel something between us, something powerful. I didn’t want the night to end. We finally pulled away from each other.

‘You going to be OK, cycling half-cut? You could leave it overnight; I could pick up a couple of bottles along the way. We could keep talking.’

‘Think I’ll sit the next dance out, thanks all the same. I’m not actually that much of a drinker?’

I faltered for a second and clawed back an image of a finger of wine untouched in the bottom of your glass.

I was mortified.

I’d drunk and blathered on about myself and my life, while you’d listened on soberly, watching as I gulped down the booze, telling you another one of my difficult little secrets, throwing in a good amount of intimate and revealing details about Iain for good measure. You’d topped me up again and again, but you hadn’t refilled your own glass once. Was it because you were one of those oh-so-serious twenty-odd-year-olds who barely drinks, needing to wake up with a clear head in order to optimise their days? Or perhaps you felt bad because you hadn’t money to pay for any of the drinks? Or was it more deliberate than this? Paranoid anxiety needled me. But I didn’t know who I should trust less, myself, or you. And I desperately didn’t want to take the sheen off those moments where we seemed to connect.

Yet dread still rose to the surface of my uncertainty and embarrassment: the sense of you wanting me malleable, that you set out to expose me and you’d succeeded. I had the idea you somehow knew the ways to see me for what I really was. And once again, I’d spent time alone with you and discovered almost nothing about you in return.

I didn’t say much else before I sloped off into the night, moving with the drinkers spilling out of Borough Market pubs in the direction of London Bridge, pissed and alone. I know you watched me as I walked away, waiting a minute or so before turning in the opposite direction. I felt it.

Lily, I knew somewhere you were no good for me, that I was unravelling again and you were tugging hard at the threads. But whatever your interest in me, you were interested.

I had been seen.

I wasn’t invisible.

I had someone new to talk to, someone I could see on the weekend, someone who had some insight into my most ancient pains. So if it seemed to me you’d barged your way into my life and under my skin, I was ready to plough right back into yours. You can’t unlearn how to fight.

And there was something else. Somewhere, I had the idea that you liked me even though you didn’t want to.