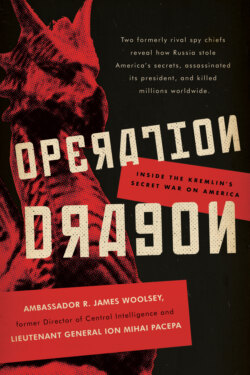

Читать книгу Operation Dragon - Ion Mihai Pacepa - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

SOCIALIST RUSSIA: AN “ILLEGAL” INTELLIGENCE TYRANNY

On September 20, 2004, a senior Democratic Party figure running for the White House said during a PBS radio interview with Jim Lehrer: “Well, let me just say quickly that I’ve had an extraordinary experience of watching up close and personal that transition in Russia, because I was there right after the transformation. And I was probably one of the first senators … to go down into the KGB underneath Treblinka Square and see reams of files with names on them. It sort of brought home the transition to democracy that Russia was trying to make.”

We understand that confusing Treblinka, a Nazi death camp in Poland, with the KGB headquarters at the Lubyanka, in Moscow, could have been a slip of the tongue. But the fact that a main runner for the White House thought that he could claim to understand Russia because he had, on a junket, viewed a few KGB archive files written in a language he could not read, is scary. To romanticize the Russian danger leaves us unprepared to face its reality.

In 2010, the FBI arrested ten Russian illegal intelligence officers, otherwise known as spies, in the U.S. But President Barack Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry deported them to Russia before they were thoroughly interrogated by the FBI about their activities.1

The American media tends to treat the idea of illegal officers akin to a joke—comic book characters, spy novel fodder, or inconsequential sleepers. For the intelligence community, however, illegals are a particularly insidious and dangerous component of espionage. To preserve the secrecy of these agents, the Kremlin goes to dramatic lengths. One example was the dramatic prison break in England on October 22, 1966, of George Blake, a former ranking officer of the British foreign intelligence service (SIS). He had been considered by his superiors as a possible “C” (chief of the entire British foreign intelligence). Sprung from Wormwood Scrubs prison, he was never seen again in the West. Blake was serving an unprecedented forty-two-year sentence for having compromised the West’s highly secret “Operation Gold” to the KGB—a tunnel in East Berlin used to tap Soviet military telephone lines during the Cold War—and the identities of some four hundred SIS and CIA officers and agents involved in that secret operation. After a tip from a Soviet bloc defector, Blake was arrested and sentenced for espionage. As far as we know, the British SIS did not then suspect that Blake was a Soviet illegal officer.

Forty-four years later, a former head of the KGB, Vladimir Putin, installed himself as Russia’s president. Two years after that, a select cluster of former senior KGB officers gathered at Lubyanka, the headquarters of the KGB, to launch George Blake’s book Transparent Walls. Sergey Lebedev, the new head of Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), wrote in the book’s foreword that, despite the book being devoted to the past, it was about the present. Blake’s book was, indeed, a message to all Russian illegal officers around the world: it is again your time.

The term “illegal” has a specialized meaning. Intelligence officers working under the cover of official representatives, such as diplomats, in foreign countries are “legal,” overt “spies.” Officers documented as natives of a foreign target country and embedded in that country for the rest of their operational lives are “illegals.”

Illegal officers might just be your next-door neighbors. They are documented as born in your country, and they speak your language with native fluency. Some might be even ranking members of your country’s administration, like George Blake. All, however, are ready to become operationally active on special occasions, such as for killing political opponents, influencing elections, or replacing the legal agents in times of war when the enemy’s embassies are shut down. Some are even prepared to create skeletons of pro-Russian governments in that country after the end of major wars.

In May 1974, the chancellor of West Germany, Willy Brandt, wrote to the West German president: “I accept political responsibility for negligence in connection with the Guillaume espionage affair and declare my resignation from the office of federal chancellor.”2 Günter Guillaume was an illegal officer of Communist East Germany’s Stasi intelligence service3 who had risen to become a staunch member of the West German SPD party and a trusted adviser to Brandt himself. Sentenced to thirteen years in prison, in 1988 he was returned to East Germany in exchange for Western spies caught in the Eastern bloc. In East Germany, Guillaume was celebrated as a hero. There he published his bestselling autobiography, Die Aussage (The Statement).

KGB officer Panteleymon Bondarenko, aka “Pantyusha,” the first chief of Communist Romania’s political police, the Securitate, starting in 1948, told Pacepa (in vulgar terms) that illegals had changed the face of Europe. Herbert Wehner, the West German SPD party chairman in the Bundestag and minister for “all-German affairs” (meaning relations with East Germany), pretended to have spent World War II as a political refugee in Sweden. In fact, as Pacepa learned from Pantyusha, Wehner had sheltered in Moscow, along with Walter Ulbricht, Matyas Rakosi, Georgi Dimitroff, Klement Gottwald, and Boleslaw Bierut. All became illegal Soviet officers charged to take over the governments of Eastern and Central Europe as soon as those countries were “liberated” by the Red Army. All carried the undercover rank of colonel except for Dimitroff, who became an “illegal” general. “All secretly worked for us,” Pantyusha explained, as Stalin did not give a “fucking kopek” for any foreign communist in Moscow “who tried to weasel out of working with us.”

It is very hard to identify an illegal officer living in the West under a Western biography. General Pacepa approved many of them. All carried original Western birth certificates, school diplomas, pictures of alleged relatives, and even fake graves of relatives in the West. In some important cases, the KGB community also created ersatz living relatives in the West—ideologically motivated people who received life-long secret annuities from the Soviet bloc intelligence community.

One of these illegals was so carefully documented that he rose to ambassador of an enemy nation. His Russian name was Iosif Grigulevich. At the end of World War II, Stalin was at the peak of his glory, but he hated Pope Pius XII, who in 1949 had excommunicated Stalin and his Communist Party. In retaliation, Stalin ordered an illegal to be tasked to kill Pope Pius XII. Grigulevich, documented as Teodoro B. Castro, the supposed illegitimate son of a recently deceased wealthy Costa Rican, was selected because on February 22, 1947, the nephew of Pius XII, Prince Giulio Pacelli (birth name, Eugenio Pacelli) had become the Costa Rican minister plenipotentiary to the Holy See.

In 1949, Grigulevich and his Mexican KGB-recruited wife settled in Rome. He was now known as Teodoro Castro, a rich Costa Rican coffee merchant. Castro bought his way into the Costa Rican diplomatic service and by 1952 had risen to the post of Costa Rican minister plenipotentiary to Italy. KGB archivist Vasili Mitrokhin, who defected to the British in 1993 (and whose information has been described by the FBI as “the most complete and extensive intelligence ever received from any source”), reported seeing Grigulevich’s personnel file in KGB archives with a note saying that as Castro he had “successfully cultivated the Costa Rican nuncio [sic] to the Vatican, Prince Giulio Pacelli, a nephew of Pope Pius XII” and “had a total of fifteen audiences with the Pope.”

On March 5, 1953, Stalin unexpectedly died, and the illegal operation to assassinate Pope Pius XII was cancelled. In 1954, Grigulevich honorably retired from the KGB. Settling down in Moscow under the name Lavretsky, he died in 1988.

A contemporary version of Grigulevich in the United States may be Bob Avakian. An American citizen, Avakian was said to be living in self-exile in Paris where he was rarely sighted. Avakian owned “revolution bookstores” in sixteen American cities, including Cambridge, Berkeley, New York, and Seattle, and he published a Soviet-style anti-American magazine called Revolution. Some years ago, Avakian formed a Soviet-style Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP), which was instrumental in sparking the 1992 Los Angeles riots and more recently in creating two Soviet-style radical organizations, Not in our Name and World Can’t Wait.

We do not yet have a contemporary source like Pacepa to tell us if Avakian is another Grigulevich. But Avakian is now at work on replacing the U.S. Constitution with a Constitution for the New Socialist Republic in North America, an American version of Lenin’s The State and the Revolution, which turned Russia into the Gulag Archipelago.

The draft of Avakian’s constitution is a disturbing read. Behind its supposedly American façade, the document is breathtaking in its Soviet-style brutality: “In order to bring this new Socialist Republic into being, it would be necessary to thoroughly defeat, dismantle and abolish the capitalist-imperialist state of the USA; and this in turn would only become possible with the development of a profound and acute crisis in society.” The RCP Constitution legalizes “special Tribunals” for dealing with the “war crimes and other crimes against humanity” committed by “former members and functionaries of the ruling class of the imperialist USA and its state and government apparatus.” These enemies of the state will “be imprisoned or otherwise deprived of rights and liberties.”4

It is an echo of Khrushchev: “Stealing from capitalism is moral, Comrades,” Khrushchev used to preach. “Don’t raise your eyebrows, Comrades. I intentionally used the word steal. Stealing from our enemy is moral, Comrades.” During the years Pacepa was his national security adviser, Ceausescu of Romania would also sermonize that stealing from capitalists was a Marxist duty. “Capitalists are the mortal enemies of Marxism,” Pacepa heard Fidel Castro inveigh in 1972, when he spent a vacation in Cuba as a guest of Fidel’s brother, Raul. “Killing them is moral, comrades!”

Was Avakian’s constitution written for the 2020 elections? Hard to say.

It will not be easy to break Russia’s five-century-old tradition of samoderzhavie, or tsarism run by political police. This was Russia’s historical form of government, and it appears to continue to be. Nevertheless, man would never have learned to walk on the moon had he not first studied where the moon lay in the universe and what it was made of. That is what this book seeks to do.