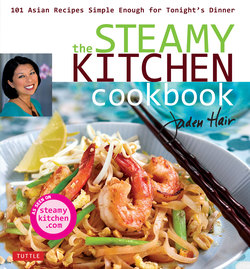

Читать книгу The Steamy Kitchen Cookbook - Jaden Hair - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеthe ingredients

I live about 20 minutes away from a good Asian supermarket and some of you even further! The way I approach Asian ingredients is to choose those that store well, like canned pastes, jarred sauces, dried aromatics and frozen goods. This way, I can make one trip every few weeks and stock up on things like coconut milk, oyster sauce, dried shrimp and frozen noodles . . . and then visit my regular local supermarket for any fresh veggies, seafood or meats. Now, a spontaneous Thai curry dinner is really simple and literally ready in 15 minutes!

Here’s a list of the most common ingredients that I’ve used throughout the recipes in the book. Take note that this is not an exhaustive list of Asian ingredients. For that I would need a volume of three more books to fill! But these are the ingredients that I use most in my home cooking: from curry pastes to fresh herbs and dried mushrooms.

My approach to Asian ingredients is that sometimes you’ve got to make do with whatcha’ got. For example, fresh Thai basil is not always available in my local supermarket, and while I normally grow this in my garden, sometimes I’ll just sub with sweet Italian basil. Same with chilli peppers—I often will use jalapeno chillies because that’s what my market carries. (And also because the spice level of jalapenos suits me perfectly!) If you don’t live near an Asian market, take a look at your grocer’s “Ethnic” aisle, and you might be surprised to find many of the jarred, canned and dried ingredients there. I’ve also tried to provide you with as many substitutions for ingredients as possible in the recipes. The Resource Guide provides sources for ordering ingredients online. And for my gluten-free friends, I’ve included notes for your diet as well. (By the way, there are SO many Asian recipes that don’t use gluten, so this is a perfect book for you if you are watching your gluten intake).

Bean Sprouts Bean sprouts, oh bean sprouts, how I love you now that I have my own kidlets to assign tail-pinching duties to! (Mom used to make me do this chore). Of course, you don’t have to pinch the tails off, the tails are certainly edible, and most restaurants and cooks will cook the bean sprouts with tails-on. Bean sprouts are the sprout of the mung bean and are one of the quickest vegetables to cook! Just a minute in the wok or blanched and it’s ready to eat. Personally, I love bean sprouts raw as a crunchy topping in my Shrimp Pad Thai (page 137), Miso Ramen (page 66) or Thai-style Chicken Flatbread (page 37). Look for white stems that snap! Here’s a tip to keep them fresh in the refrigerator. Wash the bean sprouts, discarding any that look a little soft or sad. Use a salad spinner to spin dry, or lay them out on a towel and gently pat to absorb the water. Store them in a plastic bag and also put a dry piece of paper towel in the bag. Close the bag. This is the best way to store bean sprouts . . . keep them as dry as possible! If you don’t have bean sprouts, you can just omit them from the recipe or sometimes what I do is take a long celery stalk, peel the stringy outer layer with a vegetable peeler and julienne into thin strips. The crisp-crunchy texture is very similar.

Bean Sauce or Paste Chinese bean sauce is made from fermented soybeans and different spices. There are a few different kinds of bean sauce, the brown bean sauce comes smooth or with whole beans (preferred) and is an essential component of northern Chinese cooking. It’s pretty salty, so use just a bit at first and add more after tasting. Bean sauce has an incredible flavor—both salty and savory. Black bean sauce is made from fermented black beans and is used in Clams Sautéed in Garlic and Black Bean Sauce (page 77).

Cilantro, green onions, lemongrass, Thai basil and kaffir lime leaves in the small bowl.

Bok Choy is Chinese cabbage and I love cooking with the beautiful spoon-shaped leaves (Simple Baby Bok Choy and Snow Peas, page 116). It’s commonly used in Chinese cooking and the stalks are mild and crunchy while the leaves taste like cabbage. It’s very healthy for you, full of vitamins A and C and a fab source of folic acid. My parents eat bok choy at least once a week! This is one of those vegetables that you can add to any stir-fry—you can cut them up into 1-inch (2.5-cm) sections, add the thicker stems into the frying pan first, followed by the leaves. My favorite part of the vegetable is the super-tender centers of each bok choy.

Breadcrumbs, Panko These are unseasoned Japanese breadcrumbs made from crustless bread and once you use panko, there is absolutely no wanting to go back to regular, heavy, soggy breadcrumbs. Panko are more like “flakes” than crumbs and the end result is airy, super-crisp coating on whatever it is you’re coating. You can use it to bread seafood, meats or vegetables and you can deep-fry, pan-fry (Asian Crab Cakes, page 83) or even bake for a healthier dish, like in Baked Crispy Chicken with Citrus Teriyaki Sauce (page 105). You can find panko at any Asian market and even at your regular grocer. Check the “Asian” section or the section that sells bread-crumbs. If you can’t find panko, just use regular, unseasoned breadcrumbs.

Chili, Chile, and Chilli I’ve had fiery debates going on via Twitter and email on the correct spelling of chilli pepper (the fruit from the plant . . . I’m not talking about chilli con carne). In the past, I’ve always spelled the pepper “chili”, my friends Elise and Matt spell it “chile” (as do many in America and in Spanish-speaking countries). But many of my Asian cookbooks use the spelling “chilli”. Sigh . . . how confusing! Well, I asked my friend, Michael Ruhlman, for his opinion and he cited late food historian, Alan Davidson’s Oxford Companion to Food and Harold McGee, NY Times food writer and author of many chefs’ food bible On Food and Cooking. Both believe that the double “ll” spelling is the way to go, pointing out that it is the original romanization of the Náhuatl language word for the fruit (chīlli). Whatever spelling you see in other books, on grocer’s shelves or jar of hot sauce, just remember they all refer to the fiery hot members of the Capsicum genus.

Chilli Sauce I don’t think I could ever be without chilli sauce. Wait. I think I say that about a lot of ingredients! Chilli sauce is a blend of chillies with other ingredients such as garlic, salt, vinegar and sugar. Chilli sauce is so popular in all countries of Asia, and it’s very easy to make your own from fresh or dried chillies. Of all chilli sauces, there are two that are the most popular in the U.S., one is called Sriracha and the other is the Indonesian sambal oelek—a chilli-garlic combo. A staple at many Vietnamese restaurants (though originated from Thailand), Sriracha is like ketchup with a kick! I use it for everything, yes, even dipping in french fries (mix Sriracha with mayo). Its bottle is easy to spot—look for a green cap and a rooster logo—and you’ll find it. Chilli garlic sauce, or sambal oelek, is thicker and great to add to a bit of soy sauce for a simple dipping sauce for dim sum. I also sometimes add a spoonful of chilli garlic sauce to stir-fries. Once opened, keep chilli sauce in the refrigerator. For a discussion of sambal, see page 24.

Chillies, dried You can find whole dried chillies at most Asian markets and you can soak them in hot water for a few hours to blend with some garlic or other seasonings to make a great chilli sauce, or you can throw them whole into your cooking. Of course, if you use them whole, you’ll get the lovely flavor of chilli without all the heat. I personally like to cut each dried chilli in half, empty out and discard the seeds and add the halved chillies to my dish. This way, my kids aren’t surprised with a zinger of a bite if a chilli seed (the source of most of the heat) is hidden in their food! The whole dried chilli is about 1 1/2 to 2 inches (3.75 to 5 cm) long and you can usually find them in your regular supermarket.

Chillies, fresh Of all ingredients, this is the most fun to play with. There are so many different chillies from all over the world and each has different levels of heat. In the U.S. you’ll find finger-length chillies (medium spicy) to Thai bird’s-eye chilli, which are tiny but will have you screamin’ for your mama. Here’s my tip. Use what you like and what you can find fresh in your markets. Generally (and I really do mean generally) the larger the chilli is, the less spice it packs. I try to find larger chillies because while I totally enjoy the flavor of fresh chillies, my spice tolerance really isn’t that high. Jalapenos, while not Asian, are super-fresh and plentiful in my markets and I also grow them in my backyard. If you prefer even less heat, go for the big, fat banana peppers, which are incredibly mild but still have wonderful flavors.

Chilli Powder or Flakes Asian chilli powder is dried chillies ground into powder or flakes. It’s very popular in fiery Korean dishes, like Spicy Korean Tofu Stew (page 112) and it’s the heat that makes kimchi hot! Use sparingly at first, taste and then add more chilli powder if you need to into a dish. A little goes a long way, trust me. Oh, and one more thing. After you taste, wait 30 seconds before you add more chilli powder. Some chilli powder sneaks up on you, and its effect won’t be apparent until a few seconds after you swallow! The powdered seasoning mixture, sometimes labeled as “chilli powder”, is used to make chilli con carne should not be substituted for Asian chilli powder.

Curry paste, Chinese five spice powder, cinnamon sticks, shallots, ground and whole coriander, star anise and dried red chilli pepper.

Chinese Black Vinegar This is one of my secret ingredients in my pantry. Anytime that I think a Chinese stir-fry needs a little somethin’—a splash of Chinese black vinegar always does the trick. It’s made with sweet rice that has been fermented, like fine aged vinegars. You can substitute with balsamic vinegar. You’ll find that Chinese black vinegar is that indescribably secret ingredient in Chinese Beef Broccoli (page 94).

Chinese Rice Wine (or Sherry) Shaoxing wine is the most popular Chinese rice wine, and it’s made from rice and yeast. While you can drink good quality Chinese rice wine, it’s not my cup of spirit. However, I can’t imagine cooking Chinese dishes without it! I use Chinese rice wine in everything from marinating meats to a splash in my stir-fry to an entire cup in braises. You can substitute with dry sherry.

Chinese Sausage or “Lap Cheung” is found in the refrigerated section or in the dry goods section. Chinese sausage is sold in plastic shrink-wrapped packages in Asian markets. It is cured, so it lasts for a long time like Italian sausage. Keeps for about six months, sealed in its original packaging at room temp. Once you open, seal in plastic bag and refrigerate for up to another 6 months. Unopened, they keep in your pantry for 1 year, as they have already been cured. This is another of my secret ingredients, especially in Chinese Sausage Fried Rice (page 131). Everyone who’s tried this sausage becomes addicted. I mean like loves it so much they’ll sneak in your fridge and swipe the rest of the package home. It’s salty-sweet and has little tiny pockets of fat that melt when cooked and flavor your entire dish. This is a must-try! There are few types of Chinese sausage, including duck liver. My favorite is just the regular ‘ole pork. My kids think I’m the world’s best mom when I throw a few links into my steaming rice—Chinese Sausage With Rice and Sweet Soy Sauce (page 129). There is no substitution—just buy the real thing!

Chives—Chinese. Chinese chives look like thick blades of grass—they are flat and dark green. They are stronger in flavor (and sweeter too) that the regular thin chives used in Western cooking, and you can add Chinese chives to any stir-fry, dumpling or egg roll filling. The flowering Chinese chives are stiffer, taller than Chinese chives, and are one of my favs to add to noodle dishes, like the Quick Noodle Stir-Fry (page 136). You can substitute with regular Western chives.

Cilantro. See Herbs.

Coconut milk is made by squeezing the grated pulp from a coconut, it’s not the same as coconut water (which is the water found when you open a fresh coconut) You’ll find coconut milk canned at any Asian market and mostly likely in the “Ethnic” section of your grocer (which, I hope one day will be obsolete and global ingredients will be found throughout the store). Coconut milk is unsweetened (not to be confused with sweet creme of coconut used for cocktails). There are many differences in each brand. The first pressing of the grated coconut results in very rich and creamy coconut milk (I loooove) and then the coconut pulp is soaked in warm water and pressed again. The subsequent is more watery, less flavorful. The best way to tell the quality of a coconut milk is to pick up a can and shake it. If it feels/sounds thick “schlonk-schlonk” (yeah, um, schlonking is a word) it’s good. If it’s watery “squish-squish” it’s not as good. Personally, I go for schlonk. My fav brands are Mae Ploy and Chaokoh. There aren’t really substitutions, unless you want to grab a coconut, grate and squeeze yourself. Don’t even try to sub with milk and coconut extract—I’d rather have you skip the dish entirely than go that route.

Dried rice noodles, egg roll wrappers, square wonton wrappers, round potsticker wrappers, jasmine rice tipped in the bowl, short-grained rice (popular in Japan and Korea) and dried rice paper wrappers for Summer Rolls.

Coriander, fresh. See Herbs.

Coriander, ground and whole Coriander is the seed from the coriander herb (better known as cilantro in the United States) and it can be found whole or ground. It’s got a sweet, citrusy aroma and tastes nothing like the fresh cilantro/coriander! The spice is used in lots of Indian and Southeast Asian cooking and I love using it my Quick Vietnamese Chicken Pho (page 58). If you want to make your kitchen smell amazing, toast a tablespoon of the seeds in a dry frying pan!

Curry paste, Thai Thai curry paste is sold in little cans, pouches or tubs. I recommend the little 4-ounce (125-g) cans or pouches as they are easy to store and use. If you do buy the larger tubs, curry paste does keep well in the refrigerator for several months if you store it properly and keep it covered. There are many different types of curry paste: red, green, yellow and masaman. Each is made from a different combination of herbs and spices such as garlic, ginger, kaffir lime leaf, lemongrass, galangal, and of course chillies. If you’re new to working with curry paste, it’s best to add just a bit first into the dish, taste and then adjust. With coconut milk and curry paste in my pantry, I can make a fabulous seafood dish, like Mussels in Coconut Curry Broth (page 70), or the spicylicious Thai Coconut Chicken Curry (page 103), both ready in just 15 minutes.

Dashi / Instant Dashi (Hon Dashi) is like the backbone of Japanese cuisine, flavoring everything from miso soup to braised chicken. It’s a stock made of seaweed and dried bonito flakes. Instant dashi or Hon Dashi, is used in a lot of quick home cooking in Japan, and making it so convenient to whip up a bowl of miso soup in minutes! There are vegetarian versions of dashi made from dried shitake mushrooms—though I haven’t found a vegetarian instant dashi. Also, instead of boiling frozen edamame pods in plain water, I add a couple spoons of instant dashi granules in the pot. You’ll notice the difference in the taste tremendously!

Fish sauce is an essential ingredient in my pantry. It has a nice salty-sweet flavor to it, and you use it very sparingly, like Anchovy paste. A little goes a long way! There are several brands of fish sauce, the best one I’ve found so far is called “Three Crabs”. Good fish sauce should be the color of brewed tea. Anything darker (like the color of soy sauce) is a lower quality brand. If you think that “fish sauce” sounds like a weird ingredient, guess what? A big chuck of the most popular Thai and Vietnamese dishes call for fish sauce! After opening, you can store fish sauce in your pantry or refrigerator.

Five Spice Powder Chinese five spice powder is a mixture of fennel, star anise, cinnamon, cloves and Sichuan pepper-corns. But there are different spice blends and sometimes with more than five spices. It balances all 5 flavors of Chinese cooking: sweet, salty, bitter, sour and pungent. Just a pinch is all that’s needed—it’s a strong spice and can take over the entire dish if you use too much! It’s great when mixed with sea salt to season chicken for the grill or just a few dashes can be added to any Chinese stir-fry. Five spice powder is a popular spice mix, you can probably find it at your regular grocery store.

Ginger is actually a root, the rhizome of a name of a plant I can’t say 10 times fast, “Zingiber Officinale”. It’s one of the ingredients that I use in my everyday Asian cooking. When shopping for fresh ginger, look for ginger with smooth skin (wrinkled skin means the ginger is old and dried). For tips on how to prepare ginger see Jaden’s Ginger Tips on page 33.

Green Onion (Scallion or Spring Onion) is part of my holy trinity of Chinese cooking, along with ginger and garlic. I use green onion in many of my dishes, either stir-fried with the garlic and ginger as an aromatic or sliced super-thinly on the diagonal as a raw garnish. To store green onions, remove the rubber band and place them in a small cup or glass jar that’s filled with an inch (2.5 cm) of water. Insert the green onions, root side down and cover loosely with a thin, plastic grocery bag (I store fresh herbs this way too).

Herbs, fresh Fresh herbs are used as a major part of the ingredients, especially in Vietnamese dishes. I like to stir in fresh herbs at the very tail end of cooking, to keep its vibrancy and flavors. I also use fresh herbs as a garnish on top of a dish. Yes, the garnish makes a dish look prettier, with a pop of green, but my main reason is that I love snagging sprigs of the fresh herbs onto my plate to eat with the dish. Plus sprinkling the herbs on one side of the dish or on top makes everyone at the table happy. I can scoop a portion of the dish that doesn’t have the garnish for my kids (they’ll just pick out and waste the herb) and I make sure my big spoonful includes loads of herb, whether it’s cilantro, mint or basil. To store fresh herbs, grab a glass or a ball mason canning jar. Add about an inch or two of water and stick the herbs in the glass like a bouquet. Cover loosely with a plastic bag (one of those thin plastic bags from the produce section of supermarket works just fine) and it should keep in the refrigerator twice as long as when normally kept suffocating in a plastic bag in your vegetable drawer! Cilantro (Coriander): Cilantro is what I call this fresh herb! When I was little, I didn’t like the taste of fresh cilantro, picking every little itty piece out of the dish (mom loved it). Then one day, just out of nowhere, I craved the taste of cilantro and now can’t get enough of it! (Okay, truth be told, I was preggers with Andrew and I think that had something to do with my tastes changing!) It’s the most consumed fresh herb in the world and Asians use the leaves as well as the stems. Mint: This herb is so flexible—it can be used in savory dishes, desserts, cocktails and teas. It’s refreshing and brightens any dish up. Thai Basil has a bit stronger taste than regular sweet basil that you find in supermarkets. But honestly, you can’t really tell the difference in a dish! It’s got purple stems and really beautiful purple flowers that look pretty as a garnish. Substitute sweet Italian basil if you can’t find Thai basil.

Hoisin This Chinese sauce is made of soybeans and it’s sweet, sticky and garlicky—which is why I describe it as “Chinese sweet BBQ sauce”. It’s used as a condiment for smearing on pancakes or buns for the popular Peking Duck and Moo Shu Pork dishes. I like hoisin sauce, but when I use it, it’s with a light touch and in combination with other sauces.

Kaffir Lime Leaves are used in a lot of Southeast Asian dishes—the double leaves of the tree are incredibly fragrant and one whiff will instantly remind you of Thai dishes. You can use them like bay leaves, just tear the leaf (keeping it whole) in several places and drop in your soup or dish. If you can’t get kaffir lime leaves fresh, check the freezer section or you can buy dried leaves. I also like to julienne fresh kaffir lime leaves into the thinnest slivers possible and add to a stir-fry. Substitute with a couple wide strips of lime peel. Grab a vegetable peeler and peel a strip of the thin outer green skin off the lime (avoid the white pithy part).

Kimchi I don’t think I’ve ever been in a Korean family’s home without the sight of kimchi in their refrigerator. Kimchi, or kimchee, is pickled or fermented vegetables and there are hundreds of different kinds. The one most popular is made of Napa cabbage, garlic, carrots and lots of chilli powder. It stores pretty well in your refrigerator and for me, the more it ages, the better it tastes! It’s used as a spicy condiment, though I can make an entire meal out of white rice, kimchee and a few sheets of seasoned seaweed sheets (nori).

Lemongrass I grow lemongrass in the backyard because I use it so much! Lemongrass is well, a grass, that’s native to Southeast Asia. You only use the bottom 4–6 inches (10 to 15 cm) of the thick stalk, as it’s got a wonderful light lemony fragrance and taste. Look for lemongrass that is light green and fresh looking. Lemongrass is very fibrous and tough, so you’ll either smash the stalk to release flavors and add to soups (remove and discard before serving) or mince it very finely. To use, cut the bottom 4 to 6 inches (10 to 15 cm) of the stalk (discard the rest) peel away the outermost layers of the stalk and discard. To infuse for soups, curries: slice stalk in half lengthwise. Use something heavy to bruise the stalk just a bit to release flavors. Rings: slice the stalk into super-thin rings. Mince: run your knife through the rings, back and forth to finely mince. Grated: my favorite way is to grate the lemongrass with a microplane grater. You’ll get incredibly fine lemon-grass without the fiber. I don’t like lemon-grass paste or powder (yuck). The frozen stuff is not bad, but I’d rather substitute with lemon peel. Grab a vegetable peeler and peel a strip of skin off the lemon.

Maggi Sauce Magical Maggi! This condiment is originally from Switzerland, but it is incredibly popular in Asia! It’s like a more delicious version of soy sauce, though it contains no soy (but does have wheat gluten). A few dashes is really all you need to add that “umami” (that delicious, savory taste) to any dish. Next time you fry an egg, add a quick dash of Maggi! You can substitute with equal amount of soy sauce. It can be found in the condiment section of your grocery store.

Mint. See Herbs.

Mirin is Japanese sweet rice wine, very different from Chinese rice wine or sake and it certainly is NOT rice vinegar. I know, it can be confusing, as all three are so similar in name! Make sure you check the bottle and look for “sweet cooking rice wine”. If you don’t have mirin, substitute with four parts sake; 1 part corn syrup or sugar, dissolved. If you don’t have mirin or sake, then try dry sherry or dry vermouth with the corn syrup or sugar . . . and if you don’t have dry sherry or vermouth, then white wine. If you don’t have white wine, well then it’s time to go shopping.

Miso is an essential component of Japanese cuisine and it is made from fermented soybeans. There are so many different types and textures of miso, from delicate light and smooth to chocolate brown with bits of soybean chunks. It’s found refrigerated in Asian markets and health food stores, but I bet you can also find it in your regular local supermarket as it’s becoming more and more popular. Once you open it, keep it covered well and it will last up to six months in your refrigerator. The great thing about miso is that you can just take out a little scoop and make miso soup for one. White miso is called “shiro miso” and it’s sweeter and less salty than the others. Of all miso, this is my favorite because the flavor is more delicate. The deeper the color, the saltier and generally stronger in flavor as it’s aged longer. There’s really no substitute for miso.

Mushrooms Canned, straw. This is a common ingredient in Chinese stir-fries and Thai soups. They don’t have a lot of taste on their own (like many canned vegetables) but the texture is pretty unique, kind of slippery soft. I like cutting them in half lengthwise to make it easier to eat (and it’s prettier too). Fresh, shitake. Shitake are Japanese black mushrooms, and you’ll find plenty of shitake in your local supermarket, as it’s widely cultivated now. The cap is light golden brown and the stem is woody. Store shitake in a brown paper bag in your refrigerator. Dried, black. Dried black mushrooms or shitake mushrooms are smokier and deeper in flavor than the fresh version. They are generally large and meaty and are used by vegetarians as a “meat substitute”. These can be stored for a long time in your refrigerator or pantry. To use, soak them in water until soft. The thick mushrooms must be soaked for several hours. If you’re in a hurry, microwave them in hot water. Start with 7 minutes and check. When I know I’ll be using dried mushrooms in a dish, I’ll actually soak them in water overnight. The soaking water is flavorful (discard the sediment at the bottom) and you can use this water when steaming vegetables, making rice or just adding to pot when making soup.

Noodles, dried Buckwheat (soba) noodles. This mushroom-colored thin noodle, which is popular in Japan, is made from buckwheat flour. It’s usually served chilled with dashi-soy-mirin dipping sauce (yum) or in a hot broth. Rice noodles or rice vermicelli. This noodle is made from rice flour. It’s one of the most popular noodles in Asia and come in many widths. The thin rice stick noodles are great for Vietnamese spring rolls and salads. The medium and wide widths are often found in stir-fried noodle dishes (Shrimp Pad Thai, page 137) and noodle soups (like the Quick Vietnamese Chicken Pho, page 58). Soak rice noodles in warm water and briefly boil. Egg Noodles. This pale yellow noodle is made of eggs and wheat. They are available fresh, frozen or dried. The dried egg noodles are dried in little bundles or coils. You’ll have to soak them in warm water to loosen the coils before cooking. These egg noodles are used in Wonton Noodle Soup (page 60). See page 23 for information on fresh or frozen egg noodles. Mung bean noodles. These slippery noodles are made of mung beans and are gluten free! They are white when dried and clear when cooked. They are also known as glass noodles or cellophane noodles. They can also be deep-fried (my kids’ fav!) and they magically puff up in just a few seconds time and great as a top-ping for salads or a stir-fry. Potato starch noodles. These Korean noodles are also sometimes called glass noodles and are used in the dish Korean Jap Chae Noodles (page 135). They are made from sweet potatoes and do not contain gluten. The noodles are called “dangmyeon” in Korean and are grayish in color when dried; they transform to clear color when cooked. Somen. This very thin, delicate Japanese noodle is made from wheat flour. They are usually served chilled with a dipping sauce and they are also served in broths.

Chinese rice wine, Sriracha hot chilli sauce, oyster sauce, sweet chilli sauce, soy sauce, coconut milk, sesame oil, Chinese black vinegar, fish sauce and hoisin sauce.

Noodles, fresh Fresh Rice Noodles. These are my favorite noodles of all time, especially the wide rice noodles used in a Chinese stir fry. If I can find fresh rice noodles, I’ll use them for Quick Vietnamese Chicken Pho (page 58). You can also find them in sheets that are rolled up; you can unroll them, fill them and then steam them. They don’t keep that long—they’ll dry out in the refrigerator, so use them quickly or freeze. Egg Noodles. Fresh egg noodles are sold in plastic baggies or containers and are in the refrigerated section. They are also frozen in the package and store very well. The noodles are very quick cooking, and perfect for a hearty stir-fried noodle dish like Quick Noodle Stir-Fry (page 136) and the Garlic Butter Noodles (page 134).

Nori is Japanese for thin sheets of dried seaweed, usually sold in sealed packets of ten to fifty sheets. These are for sushi making, but their crispness doesn’t last too long once you open the package. If you have a gas stovetop, turn on the flame, take one sheet of nori and wave it over the flame to toast and crisp up the seaweed for a shatteringly crisp texture. Nori also comes in other shapes—smaller squares and strips. I love to sprinkle seasoned nori on soup (Ochazuke Rice with Crispy Salmon Skin and Nori, page 59), plain rice, french fries or popcorn (page 53). Seasoned nori is usually seasoned with salt, and you’ll see that right on the package.

Oil, Cooking For my everyday stir-fry or pan-fry cooking, I use canola oil as it’s healthier than some of the other oils and it does have a high smoking point and a neutral flavor. I also recommend vegetable oil or peanut oil, however, with so many kids with peanut allergies (what’s up with THAT by the way?) I’m just afraid to use it in my cooking. Toasted sesame oil, which has dark amber color, has a very low smoking point but a pungent/distinct odor when using more than just a few drops or a dribble in a dish. Olive oil is fine to use for cooking, but the oil has a pretty strong flavor and you’ll end up noticing the olive oil taste in your Asian food.

Oyster Sauce Yes, it’s made from dried oysters. But no, you can’t really taste the oysters! It’s dark broth, thick and smooth; salty, smoky and slightly sweet at the same time. Oyster sauce is used to enhance the flavor of many stir-fries, noodle dishes and braises. There is a vegetarian version made from mushrooms, too. Once opened, keep it in the refrigerator, where it will last a long time. There’s not really a good substitute for this sauce, however it’s a very popular Chinese ingredient and you’ll probably find it at your grocers.

Plum Sauce is sometimes called “duck sauce” because it’s often served with roast duck in Chinese-American restaurants. It’s a sweet, slightly tart dipping-sauce made of plums, apricots, vinegar and sugar. It’s good as a dip and as a substitute for Sweet Chilli Sauce and even as a glaze for grilled chicken.

Rice There are so many different types of rice—jasmine, short grain, broken, sweet, brown, red and even black! The most popular rice is the long grain (I prefer jasmine rice and the short grain (used in sushi and popular in Japan and Korea). The long grain Asian rice (not basmati) is popular in China and Southeast Asia. The jasmine rice (popular in Thailand) has a beautiful aroma. Long grain rice is fluffier when cooked and the grains separate better. The short-grained rice is starchier, stickier and heartier. When mixed with a bit of seasoned rice vinegar, its texture is perfect for sushi, which requires the rice grains to stick to each other to form a ball. To cook rice, you must rinse the rice in several changes of cool water to get rid of excess starch and just to cleanse the grains. See page 129 on how to cook rice.

Rice Vinegar There are two types of rice vinegar (also called rice wine vinegar): seasoned (or sweetened) and regular (or un-sweetened). Rice vinegar is less acidic and tart than regular white distilled vinegar. The seasoned rice vinegar is perfect for dressing sushi rice or for salad dressings as it includes sugar already in the mix. Substitute the regular rice vinegar with cider or white vinegar. To make sweetened rice vinegar, take 1/4 cup (65 ml) unsweeteend rice vinegar, cider or white vinegar and add 1 tablespoon of sugar.

Salt Like the spelling of chilli (page 18) there is much confusion about salt! Not the spelling, but the fact that foodies and chefs are definitely passionate about their salts and there are different types of salts. The most common in households is table salt, but it’s also my least favorite. The granules are very fine, the taste is bitter, the anti-caking agent just sounds gross, and the added iodine is sooooo 1920s. I’m a natural sea salt and kosher salt gal. Most restaurant kitchens will use kosher salt in its everyday prep and expensive sea salt in finishing a dish, sprinkling it right after the dish is plated. I do the same. Kosher salt’s larger granules are easier to use and feel (instead of spooning salt, I always use my fingers and hands to salt) and it’s not as salty as table salt. And you can’t beat sea salt’s natural taste and flakey texture. I don’t know what kind of salt you use at home, (and since the measurements of these different salts are so different), instead of putting exact measurements, like “ 1/2 teaspoon of salt”, I’ve used “generous pinch of salt” throughout the recipes. I’m a big advocate of “season to taste” as your “salty” may be my “bland”. Start with a generous 3-finger pinch of salt (probably twice for kosher and sea salt). You can always add more.

Sake is Japanese fermented rice wine and the best sake is drunk chilled. The so-so sake is served warm to mask its inferior quality. Sake has a higher alcohol content than beer or wine, and like wine, there are many different types and price points. Daiginjo is the top quality stuff (I’d use this for drinking and not cooking). For cooking, you can always substitute with dry sherry or dry vermouth.

Sambal The word sambal refers to a Southeast Asian (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singaporean) relish or condiment made with ingredients like chillies, salt, garlic, vinegar, sugar and others. Sambal is usually served at the table, so you can spoon some on your own plate as you need. I have a sweet chilli version (page 26) that is great tossed with cooked noodles, used as a dipping sauce or topped on plain chicken.

Sausage, Chinese, see Chinese Sausage

Scallions or Spring Onions, see Green Onion.

Sesame Oil, Toasted or Dark Sesame oil is the oil from toasted sesame seeds. The dark sesame oil has a very strong flavor and fragrance, so only a few drops to a teaspoon is all that’s needed in a dish. Otherwise, your entire dish will end up tasting like the sesame oil! It’s used as part of a marinade for meat and seafood for Chinese stir-fries, but mostly added towards the end of a dish as the sesame oil smokes at high heat. Buy sesame oil in glass bottles and store away from heat and light, it turns rancid pretty easily. If you don’t have sesame oil, add regular cooking oil to toasted and crushed sesame seeds.

Sesame Seeds These itty bitty seeds are used whole in cooking for its nutty, sweet aroma with a rich, buttery, nutty taste. They come in shades of pale ivory, brown and black. The ivory colored sesame seeds are probably untoasted or unroasted. You can use them as is, but for maximum flavor, toast them in a dry frying pan on medium-low heat for 2 to 3 minutes or until golden brown and fragrant. The brown and black sesame seeds are pre-roasted (check the label) and are beautiful and provide a nice contrast in your dish.

Shallots are small, anywhere from 1 1 /2 to 3 inches (3.75 to 7.5 cm) across. They are sweeter and milder in taste than onions and are a very popular ingredient in Asian cooking. You can add them to your stir-fry along with the garlic and ginger, or you can deep-fry them for a crispy topping on a dish. Store shallots in a cool, dry, well-ventilated place, just as you would store your onions or garlic. Substitute shallots with finely minced onion.

Sichuan peppercorn Contrary to its name, the Sichuan peppercorn (sometimes spelled “Szechuan”) is not a peppercorn, but rather a berry from a bush. Put a couple of pods between your teeth and chew—you’ll get a numbing, tingly sensation all inside your mouth and lips. Contrary to what people think, Sichuan peppercorn is not really spicy in your face hot. It has a citrusy, warming and woodsy aroma and flavor. Try making a flavored salt with Sichuan peppercorn (page 24).

Soy Sauce/Dark Soy Sauce This essential seasoning is made from fermented soybeans mixed with some type of roasted grain (wheat, barley, or rice are common). It tends to have a chocolate brown color, and a pungent, rather than overly salty, flavor. Dark soy sauce is used in Chinese cooking and is a bit richer, thicker, and more mellow than the lighter varieties. I use both the more full-bodied dark soy sauce in many Chinese meat stews and braises and the lighter variety, which I refer to simply as “soy sauce” in the recipes as my everyday soy sauce.

Sriracha Sauce. See Chilli Sauce.

Sweet Chilli Sauce is my “ketchup”— it’s sweet, vinegary and just barely a hint of spice. I use it as a dip anything for Mom’s Famous Crispy Egg Rolls (page 50) and Firecracker Shrimp (page 48) as well as in stir-fries (Thai Chicken in Sweet Chilli Sauce, page 104). Two great brands are Mae Ploy and Lingham (thicker, spicier and less sweet than Mae Ploy). When my assistant, Farina, eats at a restaurant that doesn’t have sweet chilli sauce, she makes her own concoction from a combo of ketchup, hot sauce (Tabasco), sugar and salt. If you have Plum Sauce, you can use that as a substitute.

Tamarind comes in blocks of pulp (with or without seeds) or prepared in jarred form as a paste (sometimes called “concentrate”). To make tamarind paste out of the blocks, in a medium sized bowl, combine a golf-ball sized piece of tamarind and ½ cup (125 ml) of hot water. With a fork, smash and “knead” the tamarind to extract as much pulp as possible. You can also use your fingers to knead as well. The consistency should be like thin ketchup. Drain and discard the tamarind solids, reserving the water. If you’re using the concentrate form, measure straight out of the jar.

Tea leaves, whether white, green, black or oolong all come from the same bush, Camillia Sinensis. The differences arise in the processing. Green and white teas are not fermented and the oolong and black tea are semi fermented and fermented. Chinese drink tea like water and of course, loose leaf tea is best (supermarket tea bags = stale tea dust!). In addition to drinking tea, I’ve got a recipe where I’m using tea to smoke and flavor salmon (page 80).

Thai Basil. See Herbs.

Tofu/Bean Curd (though tofu sounds sexier) is made out of soybeans—soft and firm. The soft, or silken is lovely eaten as is with a ginger-miso salad dressing. It’s also used cubed in miso soup. The medium and firm tofu are perfect for baking (Baked Tofu Salad with Mustard Miso Dressing, page 64) stir frying and pan frying, as they hold up better in the cooking process (see chapter on Vegetables, Tofu & Eggs, page 108). Tofu has very little taste on its own, so it takes on whatever flavors you have in the dish. It’s incredibly healthy for you and inexpensive to buy. They don’t last too long in the refrigerator, though, so use within a few days of purchase. Tofu often comes in a plastic tub covered with a thin plastic film. Slit the film and drain all the water out. To store, you can put the tofu in a bowl or container, fill with cool water, cover and refrigerate. Check the expiration date and if the package puffs out with locked in air and the package looks like it’s about to pop, discard (tofu is doin’ something funky inside). Soft or silken tofu also comes in a paper carton that does not need to be refrigerated. It’s much silkier, smoother and more delicate than the tub version. It’s difficult to use for stir-fries (but great for Tofu and Clams in a Light Miso Broth, page 117), but handy to keep in the pantry.

Wrappers From egg rolls to summer rolls and potstickers to firecracker shrimp, Asians love to wrap their food! Wonton Wrappers: Find wonton wrappers in the freezer section of an Asian market. They are very thin and square. To defrost, place package unopened on the counter for 45 minutes, or overnight in the refrigerator. Do not attempt to submerge the wrapper package in warm water or microwave to defrost. It doesn’t work well that way. Once the package is opened, always keep the wrappers covered with a barely damp paper towel to prevent the edges from drying. If they do happen to dry, you should just trim off the dried edges. Potsticker Wrappers: Same info as above, but they are round instead of square. They are also called gyoza wrappers. Egg Roll Wrappers: Same info as above, but they come in large squares, 9 inches by 9 inches (23 x 23 cm). Look specifically for spring roll wrappers or egg roll wrappers. Where I live, my local non-Asian market has fresh egg roll wrappers for sale in the produce section. I generally will tell you not to buy these fresh “pasta sheets” that are marketed as egg roll wrappers. They are way too thick and just taste too starchy. You want very thin egg roll wrappers that crisp up beautifully. Rice Paper. Dried rice paper comes in different sizes and thickness and is used for summer rolls and is available in Asian markets. My favorite brand for summer rolls is “Three Ladies”; it’s a bit thicker and better quality than the others. Look at the ingredients on the package. Don’t get the ones that include “tapioca” as an ingredient. They are micro-thin and very difficult to handle. See Vietnamese Summer Rolls (page 44) for more information on how to use and handle.