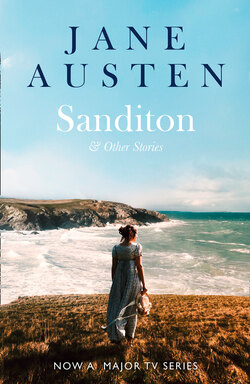

Читать книгу Sanditon - Джейн Остин, Сет Грэм-Смит, Jane Austen - Страница 6

Life and Times

Оглавление‘The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid’, says Mr Tilney in Northanger Abbey, Austen’s own opinions clearly channeled through her hero’s words. She was a devoted fan of the novel form, at a time when it was considered a frivolous entertainment – yet coming from a family of enthusiastic readers, she would go on to be one of the most enduring and beloved practitioners of the form. Enjoying minor success during her lifetime, her three unpublished novels show that there was potential for so much more, before her life was cruelly cut short at the eleventh chapter of Sanditon.

Early years

Jane Austen was born on 16 December 1775, to George Austen, a cultivated and hardworking clergyman and Cassandra Leigh, who came from a prominent family in the gentry. Their household was completed by six brothers, and one beloved sister, Cassandra. Despite George Austen’s many efforts, including some farming, and running a boarding school, the family were in constant financial difficulty. However, they were uncharacteristically literary for a family of their stature. Their library housed over 500 books, and many members of the family engaged in some form of literary activity – Cassandra wrote comic verse, while two of their brothers ran a literary journal called The Loiterer, and they all often took part in amateur theatricals at home.

It is difficult to establish much of Austen’s early biography, as her work lacked an overtly autobiographical element, even though the novels were all set in her general social milieu. Later accounts of her life are derived from letters to her sister Cassandra, and two biographies, one by her brother, and one by her nephew – both of which tend to editorialize her life through their own lens of propriety. We do know that she was a prolific writer from the young age of eleven, beginning with tongue-in-cheek parodies of the novels she found in her family library. The longest and most prominent of these is Love and Freindship, which was a burlesque of the prevalent sentimental genre of the time.

‘Female Scribblers’

It was not unprecedented for a woman to have a career in writing at the end of the eighteenth century – in fact, Austen arrived at a time when professional female authors such as Ann Radcliffe and Frances Burney were carving out a market for themselves, and making a living from their writing. Austen never became as successful in her lifetime as some of her contemporaries, but her correspondences show that she was very much involved in the monetary side of her writing career. This makes sense considering that she was allowed merely £20 a year while her father was alive, and after his death was entirely reliant upon the charity of relatives. There were very few avenues for women to make money of their own, and even if they found one, it was considered at odds with respectability. Later accounts of Austen’s life attempted to portray her as indifferent to the monetary success of her writing, but this is likely more a reflection on contemporary social norms than fact. By the end of her career it is estimated that she had made £600-£700 from her writing alone, which is not inconsiderable given her financial status.

Lady Susan

Lady Susan was one of her earliest completed works, composed in around 1795, and the only one of her fully formed novels that was written in the epistolary form. It follows the exploits of the female rake, Lady Susan, who pursues men for their fortunes without scruples. That it was never published, Austen’s nephew later attributed to the fact that Austen herself considered it unworthy, but it is more likely that social strictures of the time would have made it unpopular or risqué. Through its epistolary form, it provides a unique insight into the thoughts and desires of its female protagonist, who seems incorrigible, but is nevertheless wonderfully entertaining. Likely modelled on Austen’s worldly cousin, Countess Eliza de Feuillide, Lady Susan is unlike any of Austen’s later heroines in her vivacious amorality, though we see some of her in the likes of Mary Crawford and even Elizabeth Bennet. The story of Lady Susan forms the basis of the cinematic work Love and Friendship (somewhat confusingly titled after a different story of Austen’s), starring Kate Beckinsale – the success of which is an indication, perhaps, that the work was simply ahead of its time.

The Watsons

Austen likely began writing The Watsons in 1804, by which time she had completed drafts of three of her major works – Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey – but had not yet succeeded in publishing any. Once again, our knowledge of its composition process is coloured by the biographies written by her relatives. According to her nephew, the reason Austen abandoned the project was that she realized ‘the evil of having placed her heroine too low, in such a position of poverty and obscurity as, though not necessarily connected with vulgarity, has a sad tendency to degenerate into it’. The novel does indeed follow the lives of a family of much more diminished standing than was customary in Austen’s work, but she herself was quite familiar with financial difficulty, especially at this stage of her life. In 1805, Austen’s father died, leaving his two daughters in a state of sadness and significantly reduced standing. These personal circumstances are likely to have contributed to the fact that Austen abandoned the project. The revisions she made on the pages also give us an idea of the writing process – she seems to have struggled towards the end to conclude her narrative, with too many loose ends to tie up. She went on to use many elements from this unfinished novel in later works however, it is unique in representing the dire financial circumstances of unmarried women – a subject which is later handled more delicately through characters such as Jane Fairfax in Emma.

Sanditon – the final work

When Austen began work on Sanditon in January 1817, she was already suffering from the illness that would eventually lead to her untimely death. However, she was initially optimistic, and her buoyant and hopeful mood is reflected in the humour of the work. Yet on 18 March, she wrote the last words in her final novel, after two months’ effort. It seems ironic that her chosen topic was the life of invalids and hypochondriacs in a seaside resort, at a time when she herself was beset with illness. It shows that Austen continually viewed her own situation in a comedic light. It is also a return to the more overtly parodic tendencies of her early work, after more considered and nuanced novels such as Persuasion and Mansfield Park. The work was once again subject to posthumous editorialization by Austen’s nephew, and the novel in its entirety only appeared in print in 1925. Despite initial critical skepticism towards this later work, there is much to admire in it – Austen’s writing had become more self-assured, and she seems to have reveled in her lively use of language, as well as the incisive parody of human nature’s worst tendencies.

Sanditon, more than anything, shows that Austen was never content to continue a trajectory of writing, or to conform to contemporary norms – constantly looking ahead, and experimenting with her writing, we can only wonder where else her words would have taken her had she been granted the opportunity of a longer career.