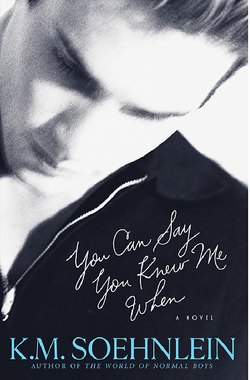

Читать книгу You Can Say You Knew Me When - K.M. Soehnlein - Страница 11

3

ОглавлениеUnlike a city apartment, a house with an attic means never saying good-bye to anything. The Garner family attic swelled with the past: boxes of moth-eaten clothing, much of it sewn in that little room at the end of the hall, and the sewing machine itself, which hadn’t been donated to the Salvation Army after all but sat here surrounded by boxes of patterns; the small plaster replicas of the Venus de Milo and Michelangelo’s David, once displayed on end tables in the living room, and the end tables themselves, carved from an ugly mustard-tinted wood; the electric typewriter, flecked with Liquid Paper, on which I’d tapped angsty poetry in high school; an outdated stereo system that my father always called the hi-fi; a German knife set that I suspected might have some value. How difficult could it be to let go of a card table—a cheap piece of junk when it was bought and now an actual piece of junk, wobbly, broken, its veneer peeling off? Or a faddish appliance—a fondue set, a Crock-Pot, a carpet broom? How about a plastic Christmas tree, originally a convenience for parents of small children but over time a tacky embarrassment?

The more I took in, the more I understood the difficulty: Everything bore my mother’s imprint. Each worthless item was something she’d chosen, no matter how long ago, or had used, no matter for how short a time. Or else it contained a dormant memory that needed only the focus of my attention to activate: the time Dee and I dressed those statuettes in Barbie doll clothes—Malibu Venus, David in madras—then waited for Dad, sighing through his nightly perusal of the newspaper, to notice our alteration, the two of us finally erupting with so much suppressed laughter that Mom dashed in to see what was wrong. Or the time a birthday party devolved into a food fight as my friends used cheese and chocolate fondue for spin art on the kitchen table. Mom was furious at first but eventually relented, flinging a forkful of wet chocolate into my hair.

I came upon a stack of boxes, each labeled, in black Magic Marker, LEGAL, and used my fingernail to slit one open. Inside was everything related to the lawsuit my father brought against the hospital where my mother had died. I pulled out a few manila folders and scanned the contents: research into heart disease, photocopies of my mother’s medical history, correspondence between doctors and lawyers. Medicine and law, two languages good at obfuscating meaning. I dug some more, not even realizing what I was looking for until I found it: a file folder marked SETTLEMENT. I read a memo from my father’s lawyer, spelling out the situation. After weighing all the evidence, the judge in the case was prepared to decide against him, to give him nothing. My father was advised to accept a settlement of one hundred thousand dollars, enough to pay his attorneys and the private investigators they’d hired and have a little left over for himself, and to promise, in exchange, to drop any threat of appeal. A hundred thousand dollars was more money than I’d earned in my entire life, but considering the many years he’d spent on the case, and the fact that he’d once spoken confidently of millions of dollars in damages, my father must have seen this as next to nothing. I couldn’t quite believe it had collapsed this way, a decade-long odyssey abandoned with the scrawl of “Edward Garner” on the bottom line. The lawsuit had never been about the money for him, but about getting someone to take blame for his wife’s death. And no one had.

I hadn’t thought about any of this in years—the shock of her death, the way it extinguished in him what little mirth he’d had. (Never again would he laugh at something as silly as the Venus de Milo in a bikini.) I felt an ache behind my eyes, along my neck, and a pressure pulsing in the air around me. I should have gone to New York like I’d wanted. I could have been ambling in and out of galleries, shopping for cheap sunglasses on St. Mark’s Place, smoking a joint with old friends while we reminisced about the shit we stirred up in our twenties.

You have to own your issues. This was Woody’s voice, the therapeutic language he relied on, which drove me crazy but tailed me everywhere. He’d spent years in therapy, not because of any particular catastrophe, but to develop a protective coating against life’s unexpected twists. You have to deal, he liked to say, and you have to be ready. I thought of my family as having been dealt a lousy hand, one with the Death card smack in the middle; we had never figured out how to play our cards. When I left my family, I left my issues behind. Now here I was back at the table. Okay, I would stay a little longer, long enough to feel these old aches, admit to them, own them, then get back to the home I’d made for myself, where I could put them to rest, once and for all.

The sun slid past the tiny windows under the eaves. I pushed past the legal files, dragging a floor lamp on an extension cord, and found other items that had been my father’s—not my mother’s or theirs together, but his alone. A bowling ball and shoes (he’d played in the town league), his Army uniform (he’d done a few years of peacetime duty in Germany, where he’d met my mother), a tuxedo that might have been the one he was married in (no wedding ring in the pockets). I had my eye out for that unexpected something that would ignite the proper emotional epiphany; I would carry this home to Woody to show him that I’d done the work.

After uncounted hours, I didn’t find much. My father was a pack rat, something I realized I shared with him. My father had never gotten over my mother, something I already knew. My parents’ tastes were tacky in a mid-seventies kind of way—something of a badge of honor for a thrift-store hound like me. I could search here all day and never achieve the desired epiphany. I stood up quickly, steadied myself against the wall while the head rush flooded in, shook the pins and needles out of my limbs. I grabbed the case containing the German knives, which would make a good gift for Woody, who never put any effort into stocking his kitchen. I turned to leave.

Then my sights landed on a taped-up shoebox marked SAN FRANCISCO. It sat atop a dresser near the door; I must have walked right past it on the way in. I stopped and picked it up. In smaller print was written JUNE ’60–JUNE ’61. Another reminder that my father had once lived in my adopted city.

What had he told me about that time? If I remembered correctly, he chose San Francisco because he had a friend there, and because back then, we all thought we wanted to be beatniks. He worked odd jobs but never made much money. He saw Monk play live. And, oh yes, his most dubious claim: He had encountered Jack Kerouac, King of the Beats himself, at a bar in North Beach. They had a brief exchange of words; Kerouac was embarrassingly drunk and hostile to his young fan’s enthusiasm. Not long after that, my father returned to New York, broke and disillusioned with all things beatnik. That’s all I knew. A sketch, barely an outline.

Even years ago, when I was still making the occasional phone call to my father, I never bothered to find out more about his time in San Francisco. Our calls always flared into harsh verbal volleys—him lecturing, me reacting—and after each one, with nothing but scorched earth left between us, we retreated a little farther from the heat. The Kerouac story is a good example. I never believed it had happened because of the way he’d used it against me: a cautionary tale about the perils of rebellion, individualism, artistic freedom. Eyewitness testimony to the harder they fall.

How strange to discover that he had saved things from those long ago, much disparaged days. How curious.

I looked again at the dates on the box. My father had stayed only a year in San Francisco. I’d lasted a decade. When I first moved there, he called it Never-Never Land. He was certain I would retreat back East, just as he had. Had I stayed so long just to prove him wrong? As I stood there, surrounded by the full sum of his life—the domestic clutter, the orderly boxes, the failed lawsuit—this seemed like a real possibility. If so, then I guess I’d won. I’d held out. He was gone, and I was Peter Pan.

I heard another voice, that of my friend Brady, who edited the radio show I’d produced: It’s all material, dude. Freelance producers are always on alert for the next story, an item to be exploited. When something of so-called human interest drops into your hands, you’re obliged to notice. To take interest. See where it leads.

When I left the attic, I took the box marked SAN FRANCISCO with me.

That night after dinner, Deirdre sat me down, with Andy at her side, and told me that they were going to move Nana to a nursing home. Not a nursing home—something for people more active than that. Senior housing. They’d worked it all out. There was a place just one town over. Nana could stay there all week, with people her own age, and she’d be able to leave on weekends and visit with Deirdre.

“She can’t be by herself all day,” Deirdre said. “She’s not that strong.”

“But she used to stay here alone with Dad,” I said, “and she managed for both of them.”

“With a lot of help from your sister,” Andy interjected, patting her hand protectively.

Deidre said, “You haven’t seen how she slips sometimes,” then paused to exhale, clearly trying to remain calm. “I want to go back to work. I talked to Carly Fazio and she said her company needs someone in human resources.”

“Who the hell is Carly Fazio?”

“From high school.”

Right: a dark haired girl at the periphery of Deirdre’s social life, that little gang of girls occupying our living room every afternoon, watching General Hospital, drinking diet soda and French braiding each other’s hair. I couldn’t summon up a face, much less where she worked, but here she was, Carly Fazio, playing her tangential role in our family drama. I’m sure Diane Jernigan knew all about her.

“What does Nana have to say?”

Deirdre averted her eyes. “We haven’t talked to her yet.”

“There’s money for this,” Andy added. “I’ve been investing Teddy’s settlement money in tech stocks—software, search engines, portals. The money these start-ups are making! It’s incredible.”

“How much did he leave behind?” I asked.

“Two hundred and fifty thousand,” Andy said. “More or less.”

I hadn’t given a thought to my father’s estate, but as this astronomical number hovered in the air, I found myself instantly calculating my share. I lived check to check, only a few hundred bucks in savings, and I had student loans to pay, and credit card debt piling up because I rarely covered more than the monthly minimum. I’d been treading water financially since college. Even a tenth of this money would make a world of difference to me.

Andy talked at length, and proudly, about his investment strategy. Online trading was his new religion. His day job at the payroll company where he’d worked for eight years offered little room for advancement. “And the office politics,” he said, “could drive a guy berserk.” Andy was upstanding—he spent time with AJ, followed the Mets religiously, shunned hard liquor because he just didn’t like the taste—but I harbored a kernel of resentment toward him. He’d knocked up my sister at age twenty-three, before she’d figured out who she wanted to be in the world, before she and I could form an adult friendship. According to this scenario, Andy had created the Deirdre of today, with the minivan and the do-list and the membership at Big Savers, as opposed to the Deirdre who once sneaked my cigarettes, who might have followed me down the path of rebellion. Now Average Andy controlled my father’s two-hundred-and-fifty-thousand-dollar portfolio. As Deidre returned from the kitchen with three bottles of Bud Lite and took a seat, almost deferentially, at his side, I saw him for what he was: the new head of the family.

“Care to tell me what the terms of his will are?” It was terrible to hear my money hunger exposed, no matter how indirectly I’d tried to phrase the question.

Andy explained that most of the money was earmarked to take care of Nana, some of it was set aside for AJ’s education, and the rest of it went to Deirdre and me. Well, mostly to Deidre. “If you want,” he said, “I can invest your share. With the way the market’s working, I can grow it fast.”

Deidre sat quietly, but I felt her watching me. When I raised my eyebrows, telegraphing a question to her, she said, “Ten thousand dollars. That’s what he left you.”

“Well.” I took a long slug from the bottle. I don’t even like beer, much less watery shit like this, but in that moment I couldn’t drink enough of it. I wanted it to flush away the hope I’d let myself feel. “What is that, about two percent? Seems about right.”

Andy cleared his throat. “I wish there was more for you. We both do.”

“Don’t worry, Andy.”

“No, I got to say, it’s sad to me, you know?”

“Seriously. I’m surprised I got anything.”

“But you and him not getting along? As a father myself, I can tell you nothing would get in the way of being close to my son.”

“Well, talk to me the day you catch AJ sucking off his boyfriend.”

His face froze.

Deirdre yelped my name. “You are unbelievable.”

“Sorry,” I said. “But you never know.”

“Guess not,” Andy said, his voice almost hoarse. Poor guy. I could see the wheels spinning behind his eyes, his thoughts trapped helplessly by the muddy image I’d set forth. Finally, he shrugged. “I guess a guy doesn’t want that for his only son. I mean, I can’t lie to you. I don’t want that for AJ. You want your kid to not be different, not get pushed around. You want grandkids some day, and so forth. That’s natural, right?”

“Actually, I think it’s learned.” I paused to figure out how much I wanted to get into this. “With me and my father, Andy, I don’t think it was about grandkids.”

“Jamie, Dad was in denial about everything,” Deidre said, her voice nearly a wail. “Look at the lawsuit! Look at the way he treated Andy at first! It wasn’t until AJ was born that Dad could even admit we were married.”

“But with me, he never admitted—” I cut myself off and lowered my voice. “Why should everything have been so tough for him? The rest of the world knows how to change. But he never did.”

“He was scared,” Deidre said.

“Of what?”

She shrugged, gave her hair a shake. The mystery at the core of our father.

After a long pause, Andy lifted his beer and said, “He’s in a better place now.”

“He found it in his heart to leave his faggot son a little something,” I said. They both flinched, but I just raised my bottle. “Let’s drink to that.”

That night I sat cross-legged on the bed, the San Francisco shoebox open in front of me. Inside was a stash of souvenirs: a collection of bar coasters advertising long-forgotten brands of beer, a map of the city, a tourist guidebook, a San Francisco Examiner announcing John F. Kennedy’s election. I flipped quickly through a small notebook filled with crude pencil sketches—eucalyptus trees, Victorian architecture, the Golden Gate Bridge—and scrawled handwriting, little fragments of a diary. I read one at random. It described an afternoon spent riding around with someone named Don Drebinski: Seems like Don knows every madman and pants-wearing chick in Frisco, and he’s introducing me to all of them. I skimmed a handful of letters from Aunt Katie, chatty with news of her engagement to Angelo, then sat transfixed over a single page written to my father from a woman named Ray Gladwell—a married woman with whom he, and evidently a couple of other guys, too, had been having an affair. I believe in the freedom of the individual, she asserted, spelling out her reasons for dumping him.

My father had gone to California to follow his beatnik dream, and remarkably, he seemed to have succeeded. Nothing in this box indicated the disdain with which he’d always spoken of his time there. After just thirty minutes I was light-headed with astonishment. This was indeed material.

And there was more. Buried beneath an old, rippled paperback edition of On the Road was a photo, an actor’s head shot, the carefully lit and formally composed image of a beautiful man’s face. Beautiful in a sparkling, pretty-boy style—dark, inviting eyes, thick lashes, glossy hair, full lips in a full smile—like Frankie Avalon or Sal Mineo, an ethnic pretty boy, softened at the edges to make teenage hearts race. The name DEAN FOSTER was imprinted at the bottom. A message was scrawled on the photo in black ink:

Rusty—

You can say you knew me when

—Danny, Los Angeles, 1961

To dip into the vernacular of Los Angeles, 1961, Dean Foster was a dreamboat, a pinup. And he was someone my father once knew. At the bottom of the box I found a dozen photos bound in twine, pictures of my father and this guy, snapped in the old neighborhood: blowing out sixteen birthday candles; dressed in suits and ties, squiring a couple of dolled-up girls to a dance; posed in front of a shiny Chevrolet, arms over each other’s shoulders. This dazzlingly handsome actor was at my father’s side for every childhood milestone. Dean Foster. Danny.

One photo was so striking I gasped out loud. It was an image of departure, dated on the reverse side, in my father’s half-legible scribble, April 18, 1960. The rear of the Chevy fills the frame, the car showing signs of wear—a broken taillight, a dented fender. Dean/Danny clutches the handle of a suitcase he’s hoisting into the trunk. His arms and the suitcase blur with motion. His heavy-lashed eyes, meeting the lens just as his image is captured, reveal annoyance. Even so, his face is spectacular, its natural Mediterranean beauty more seductive here than in the doctored studio shot. I wanted to know where he was going in April 1960. Perhaps to Los Angeles, ready to transform himself into a Hollywood actor. Or maybe to San Francisco; he might have been the someone my father said he knew there.

You can say you knew me when. But as I tried to remember if Dad had ever said anything about a Danny or a Dean, I came up empty.

The next day, I found my grandmother in the kitchen. “Nana, do you remember this guy? A friend of Dad’s?” I held up the photo of the boys in front of the Chevy.

She’d been rinsing dishes in the sink—she never used the dishwasher, considered it money down the drain—but suddenly she stopped and dried her hands on a towel. She took the photo from me. “Angelo’s brother.”

I thought she misheard. Danny did look a bit like Uncle Angelo, Tommy’s late father, but—“No, this isn’t Angelo. This is someone else. I think his name was Danny.”

“Yes, Danny, the brother of Angelo.”

I was unprepared for this. If Danny was Uncle Angelo’s brother, that made him a Ficchino, practically family—my uncle by marriage—which made it all the more surprising that I’d never heard a thing about him. “Is he alive?” I asked.

“He went to California.”

“And never, ever visits? Or calls?”

She shrugged. “I don’t keep track.”

I held up Dean Foster’s head shot. “I also found this one.”

She stopped wiping and came closer for a look. “Dear, yes.” Her stare softened. “He was going to be a movie star. We saw him once, in a picture. We all went to Times Square when it opened. Everyone from the neighborhood.”

“That must have been exciting.”

“Sure, and we dressed in our Sunday best. Danny came out of a limousine, wearing a white tuxedo jacket, with an actress on his arm.” In her broadening smile, the first I’d seen on her all week, I understood the pleasure of the memory, the trickle-down glamour of the spot-lit movie premiere, everyone dressed up to celebrate a local boy made good. “It was a picture for teenagers, one of those beach movies. He was in a bathing suit, with a surfboard. We were so excited when he came on the screen.”

“I’ll bet,” I muttered. Visions of dreamy Dean Foster: shirtless and sun-drenched.

“Mrs. Ficchino yelled, ‘That’s my son!’ You remember Mrs. Ficchino? She sure had the gift of the gab.”

“I remember her. But what happened to him? Danny?”

The sound of the car in the driveway intruded. Deirdre returning from grocery shopping.

“There was some trouble. With the police, maybe.” Nana narrowed her eyes, as if peering into a dark corner. “You could ask Katie.”

Deirdre entered, arms heavy with stuffed paper bags. I tried to squeeze in one last question. “Do you think he’s still alive?”

Before Nana could answer, Deidre asked, “Who are you talking about?”

“Danny Ficchino.”

Her eyes did some kind of mental search. “Oh—him.”

“You know who he is?”

“Yeah, sure. Uncle Angelo’s brother.”

“How come I’ve never heard of him?”

“You probably weren’t around when it came up.” Her gaze moved past me to Nana, trying to determine, I think, if I’d said anything about our conversation last night. She maneuvered from cabinet to fridge to cupboard, a blur of dyed-blonde hair and Old Navy primary colors, putting everything in its place, all the while recounting the successes and failures of her shopping trip. “They didn’t have the ______ so I got the ______ instead. The such-and-such was on sale. The whole place was a zoo.” At some point during her masterful navigation of the kitchen, she glanced down at the head shot and then back up at me, and I saw something in the set of her expression that reminded me of our father’s brand of silent disapproval.

“I found it in the attic,” I said, but she only looked away.

AJ was moving through the doorway, struggling under a grocery bag loaded with bottled juice. I stepped toward him to help, but he was determined to go it alone. “I can carry one bag at a time,” he announced with the pride of someone granted an honor.

“There’s more where that came from,” Deirdre said to me. “Get to work.”

I shuffled off obediently to make myself useful.

My last night in New Jersey. Deirdre came over to say good-bye and to find out what progress I’d made on the do-list.

I poured her a drink, made her sit down. I told her about the San Francisco box, the photos, my conversation with Nana. I asked her what she knew about Danny Ficchino. She said that Dad had mentioned him only once or twice, general stuff about running around the neighborhood with Danny and losing touch with him after Danny became an actor. He’d hinted that Danny might have had a run-in with the law, which led to a falling out between Danny and the Ficchinos. Deirdre wondered if it had been over money. “It sounded to me like one of those Italian things,” she said. “You’re dead to me now. You know what I’m saying?”

“I know it firsthand,” I said, with a gulp of the strong cocktail I’d poured.

“Oh, please, Jamie. No one disowned you.”

“Dad basically did. Why can’t you admit that?”

“I’ve never denied that he was closed minded.” She looked down into her glass, clinking ice in a shaky grip. “But you stopped trying.”

“He didn’t want anything to do with me!”

“Well, you definitely returned the favor.”

“But he sure got the last word. Ten thousand dollars just about says it all.”

We tried to keep our voices down, aware of Nana upstairs, but each recrimination was louder than the last. It wasn’t a new quarrel—we’d swiped at each other over the phone for years, she insinuating that I’d abandoned her to Dad’s illness, me insisting that she never stood up for me—but it was more ferocious than usual, the situation more desperate. I was leaving the next day, and who could say when I’d be back? She wanted to know why I wasn’t staying longer, why I hadn’t done what she’d asked me to do, why I was dredging up ancient history when there was so much going on right now. She complained that I’d taken no interest in AJ; I replied that she’d taken no interest in anything in my life. Deirdre: “You have no concept of what it takes to raise a child.” Me: “You have no concept of anything else.” Dee: “You’re the most judgmental person I know.” Me: “You’re turning old before your time.”

We amped each other up and wore each other down until we were both crying. That is, she was crying, wiping fat tears as they spilled, and I was struggling with dry mouth, a tightened-up throat, eyes burning at the tear ducts—as close as I get to crying in front of anyone else.

Over and over she said, “I can’t think. I can’t think. I can’t think.”

I stared into the fireplace, which hadn’t been used in years, though it was always roaring when we were kids. It was our mother’s domain; she was the only one who could really get it going, and after she died, it sat cold. Its square black mouth seemed, in this moment, to be the very medium through which she’d been sucked away from us; and him, too. The long corridor to the underworld.

I moved nearer to Deirdre, and I said I was sorry. I’m not exactly sure what I was sorry for. Not for my accusations, which I felt, at their core, were true. More for upsetting her—for just being me, I guess, insensitive, defensive, emotionally retarded me.

Deirdre slumped toward me, and I let my arm fall tentatively around her. Having just fought, this physical nearness was unnerving. I smoothed her hair, which at the roots was a nondescript, mousy brown, so plain compared to the fiery red of mine. Slowly she emerged from her tears. Soon enough we were telling old stories, and laughing a little, remembering funny things about Dad and his bearing in the world, like the way he used to insist he was six feet tall, though he fell short even in shoes, or the way he shined those shoes every Sunday night, lecturing me on the importance of starting the week with your best foot forward. She told me how the dementia, before it got terrible, actually made him docile, even sweet, in his dependence. We talked about how much he loved our mother, how she had protected him from the world, how he had never gotten over her.

“Since he’s died,” Deidre said, “I’ve missed her all over again.”

“I can’t let myself,” I said. “I sometimes forget I ever had a mother.”

She looked at me with puzzlement, then blew her nose one last time and threw a damp, crumpled tissue onto the coffee table, where it bounced against the crumpled tissues already there. I walked her to the front door, and we said good-bye awkwardly, like strangers on a descending airplane who’d spoken too intimately and would never meet again.

“I do wish you could stay longer,” she said.

“I’ll make a point of coming back soon, to help out with Nana and the house.” I doubted either of us believed this.

Standing alone in the hallway, listening to her minivan move down the street, I felt myself very far away from all of them—physically far away, even from Nana, asleep upstairs. I phoned Woody, but got only voice mail; I phoned Brady, Ian, Colleen—my closest San Francisco pals. I left messages for them all: “Get the margaritas ready. I’m coming home.”

Back in the sewing room, I lit a cigarette and blew smoke out the window while I packed my bags. It didn’t take long; I hadn’t brought much with me, and the only thing I was adding to my load was the knife set. And, of course, that shoebox.

I shuffled through the box one more time, mesmerized by the photos. Rusty and Danny, in front of that Chevy: my father, pale skinned and broad chested, pulled in close by his impossibly good-looking friend. Two boys with nothing but adventure ahead. I heard the click of the ignition, the roar from under the hood, a doo-wop song on the radio.

And that head shot: Dean Foster’s eyes beckoning, his lips drawing sensuous curves into his skin. Eyes and lips working in tandem, conspiring to ignite desire. My reporter’s instinct felt it as a dare: the primal male friendship of my father’s life, covered in secrecy, a forty-year silence so total there had to be a good reason for it. How to reconcile this discovery with the memory of my father as he’d lived, a man I’d never known to have close friendships with other men, who had failed to find any connection with his only son, who’d always been, to use Woody’s words, emotionally unavailable? A shiver skipped down my spine, like a stone disturbing the surface of deep water, and in the second it took to shake off the sensation, I knew what I would do: I’d look for Danny Ficchino. If he was still alive, I’d find him. I’d find out why he had been erased from our family’s history.

I found myself wishing I had tried harder to interest Deirdre in this. Her curiosity would make things easier; she could go through the rest of Dad’s belongings in the attic. Plus, we’d have something new in common, a project to get excited about together. This wish—that his death might afford us common ground again—flared at the edge of my thoughts like a shard of glass catching a beam of light. Flared, then dimmed. My sister’s needs, I knew, were more practical right now. She had a husband, a child, a house to manage; she had our grandmother’s future to consider; she had Carly Fazio in human resources ready to sign her up. If I truly wanted to be closer to her, I would have come home last year, not last week. If I wanted to delve into an obscure year from our father’s past, I would have to go it alone.