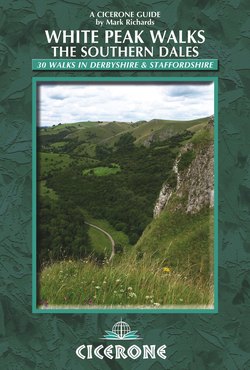

Читать книгу White Peak Walks: The Southern Dales - Mark Richards - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

National parks have their cultural origins in the US with Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, established in 1872. Yellowstone – managed for, and on behalf of, the American nation – was the first of over sixty major tracts of virgin natural heritage land purchased before Western-style despoliation.

Traditionally in England, by contrast, all land has been privately owned, until first the National Trust and then later the Peak Park Authority began to purchase particular areas of countryside for the public good and the welfare of the wild land itself.

In 1951 the Peak District – 555 square miles of breathing space between the cities of Manchester and Sheffield – became the first National Park in the UK and rightly so. It has everything a truly national landscape should: cultural integrity, geographical variety and vitality, treasured wildlife habitats and a diversity of recreational opportunities. In short, it is a landscape of the emotions, to treasure and inspire for the health and wealth of the nation. It is also ideally situated for the recreation and well-being of a huge ‘doorstep’ population.

Swallow Brook valley and Chrome Hill from the summit of Hollins Hill (Walk 13)

Bunster Hill and Thorpe Cloud from the path rising from Mapleton (Walk 27)

This much-loved upland marks a major landscape transition. Suddenly the placid woods and pastures of middle England are exuberantly transformed into modest mountainhood. Soothing ridge and furrow farmland turns to high rolling pastures and enchanting craggy dales. It is here that the North is born upon the swelling slopes of the emergent Pennine chain, the distinctive spine of England. The oldest folk name for the area is Peakland, ‘land of the peac-dwellers’. Derived from Old English, it captures the characteristic pointed hills of the area known as the White Peak.

The White Peak takes its name from the underlying limestone, in contrast to the flanking scarpland moors of millstone grit, expressively known as the Dark Peak. The core carboniferous limestone formed in a tropical sea some 350 million years ago was ringed by coral reefs, the basis of such amazing little peaks as Parkhouse Hill and Thorpe Cloud. The millstone grit that once overlaid the limestone was scoured away by glacial erosion. Where it remains, this coarse rock dominates the near eastern, northern and western horizons of the White Peak in the form of escarpments and heather moorlands. Some of these feature in this book and its companion volume The Northern Dales as they make patchwork incursions and offer fascinating viewpoints and perspectives into the plateau.

Bronze Age to Barn Conversions

Almost every hilltop in the incised plateau of mountain limestone at the centre of the Peak District is crowned by a Bronze Age burial tumulus, locally known as a ‘low’. (Both the highs and the lows of the Peak are elevated and uplifting!) Man has always found a sustainable living and ancestral inspiration in this special land. Stand upon the summit of Mam Tor or in the midst of Arbor Low stone circle and you feel the enduring magnetism this rolling hillscape exerts. Faintly traced over the limestone uplands are hints of a long agricultural past. The grey-lichened irregular enclosure walls chequering the plateau eloquently express that continuing sense of longevity, proof that man and nature have succeeded in finding a durable common cause.

Despite the damp climate, the permeable carboniferous limestone bedrock has given the capture and year-round availability of water a heightened importance for human settlement and farm livestock. All White Peak and even some Dark Peak villages keep alive the ancient practice of well dressing, founded on the perennial fear of a loss of life-giving water. These colourful and imaginative displays attract visitors throughout the summer. They may seem symbolic in this age of piped mains water, but whether you consider water God-given or – as the pagans felt – a reward for a respect for Mother Earth, it can never be taken for granted. It is ultimately part of nature’s dominion.

Herb-rich White Peak pasture near Alstonefield (Walk 21)

The sensitive wanderer may concur that Peakland is a pastoral rhapsody. With sheep and cattle the mainstay of agriculture there is a special pleasure in striding through a succession of herb-rich meadows, past grazing flocks and herds, occasionally pungent with the whiff of field-spread slurry. You may spot the odd landsman checking his stock, quad-biked, or aboard his tractor mowing or harvesting silage. Rusting machinery may be spotted in field corners making a link with the recent past. Intermingled with this farming life another more intimate and eye-catching world exists. Through the summer months a wealth of wild flowers clings to field margins, rocky ledges, secretive dales, woods and byways. Many walkers halt before a lovely scene and on lifting their cameras find they are drawn to focus instead on the enchanting petals delicately swaying in the foreground, like the delicate blue flowers of the meadow crane’s-bill against the irregular backdrop of rustic field walls.

Black Lion Inn, Butterton (Walk 3)

Although full of recreational opportunities the Peak District is every inch a working landscape. Stone quarries abound in both rock zones, some dormant and others active, a dominant component of the modern economy. Lead mining has left its mark and the vestigial traces can provide intriguing discoveries on many a walk. You may notice that the shallow lead rake workings are universally orientated east/west because this is how the veins intruded laterally. In village houses and churches we witness how the local stone has yielded to man’s desire to transform it into something more than the merely functional (although most limestone rock is crushed and wheeled away on lorries for other purposes).

Hollins Hill escarpment (Walk 13)

Stile at Steps Farm (Walk 4)

The handsome spa town of Buxton would grace any national park, but limestone quarries to east and south sadly denied it any chance of inclusion. Nonetheless, the built environment and the rural landscape are by and large harmonious and the buildings are a fascinating part of the outdoor experience. Many people brought up on the doorstep of the Park – from Sheffield to Derby in the east, from Manchester to Stoke in the west and even down to Birmingham in the south – share an understandable desire ultimately to make their home in one of these distinctive communities. And this process ensures their reinvigoration and the restoration of many a humble cottage and the sympathetic conversion of retired barns.

From Protests to the Park Authority

The Peak District holds an exalted place in the history of the campaign for public access to wild places in England. It is a movement that can trace its roots to the formation of the Hayfield and Kinder Scout Ancient Footpaths Association in 1876. The years that followed were scarred with many bitter disputes and confrontations – some petty, some serious. The Sheffield Clarion Ramblers held the first mass trespass gathering in the natural arena of Winnats Pass in 1927, but five years later came a much more significant incident.

In 1932 local working class ramblers took a stand, or rather a march, en masse, walking over a forbidden heather moor, ascending William Clough from Bowden Bridge near Hayfield aiming for Kinder Downfall. This notorious ‘Kinder Trespass’ set off a bang that resonates still, and eventually unravelled the unjust exclusion of the public from vast tracts of open country. At last the soul of society was let free to roam the wild places. Twenty years later the national parks were established to meet the greater need, to recognise the importance of particularly cherished landscapes for the nation, and to introduce hands-on management, for with liberty comes responsibility.

Since its establishment the Peak Park Authority has gained an honourable reputation in defence of the intrinsic character of these uplands, frequently having to strike a delicate balance between serving the vital recreational needs of a vast urban population and those of the local inhabitants. No planning authority has a completely unblemished reputation and although a tiny proportion of the 40,000 people who live within the Park’s bounds do see the Authority in a negative light, it is clear that the long-term well-being of the resident population is their prime concern. It will only be through the continued fostering of a closer harmony of interest that the future well-being of the area will be secured. The Park Board does have a strong local composition to ensure a genuine care for the land and its economic viability.

Walking In the White Peak

In September 2004, following the implementation of the Countryside and Rights of Way (CROW) Act 2000, the map of the Park gained a fresh impetus for walkers: the valley system of the White Peak became Open Access land. Hitherto ‘wild’ dale rims and pockets of rough land became available to the wanderer, but with this liberty comes a shared duty of care. The many precious gifts of nature cling precariously in these places and over-exercising of these ‘rights’ can cause delicate plants and creatures unnecessary stress.

Be sparing with your visits and conscious of your imprint. Many walkers also eagerly bring their best friends – by which I mean their canine chums. Please be aware that you may well encounter farm stock on the paths so keep them on a tight rein and ‘lead’ them not into the temptation of running free.

Sheep talk at Rushley Farm (Walk 12)

Curious cattle at Weags Barn: ‘You ask him.’ ‘No, you ask him.’ (Walk 8)

The White Peak offers an amiable environment for walkers despite the vagaries of its climate. Lively streams run alongside verdant pastures grazed by cattle and sheep; blocks of woodland are dissected by countless walls; limestone outcrops fringe the dale edges and complete the interplay of green and grey. The villages fit perfectly into the age-old mosaic.

The one discordant note of recent decades has been the industrial extraction of stone, bringing lorries to the district’s roads in profusion. But once away from the roads the walker has an extensive and well-maintained footpath network to enjoy. Walkers can feel at ease and relaxed in their wanderings as in few other places in England.

Wolfscote Dale: a nonchalant resident grey heron, intent on food (Walk 17)

The River Dove at Washgate Bridge (Walk 13)

Walkers descending the lovely dry valley backing Wetton Mill (Walk 9)

The Southern Dales

These two companion guides to the White Peak have been divided along the axis of the High Peak Trail, between Buxton and the Cromford Canal, near Matlock. This recreational adaptation of the Cromford & High Peak Railway forms a high spine over the plateau and a convenient, if arbitrary, dividing line. The southern portion of the White Peak is shared between the counties of Staffordshire and Derbyshire, the boundary flowing with the twists and turns of the beautiful River Dove. The Rivers Dove, Manifold and Hamps are born in the west upon Staffordshire Moorlands gritstone draining from Axe Edge and Morridge. The Hamps takes summer leave on reaching the limestone. Sinking underground and bypassing the valley junction with the Manifold it careers by some secret under-hill course to emerge in the grounds of Ilam Hall. The Manifold, which too has a similar fear of summer sunshine between Wettonmill and Ilam, runs through delightful countryside below Flash and Longnor and is particularly enchanting along the sinuous course of the old railway trackbed Manifold Trail, with Ecton Hill, Wettonmill and Thor’s Cave the primary scenic moments.

The Dove captivates in all its dimensions from the excitement of Washgate and the Dowel Dale hills, by Pilsbury and Hartington and into the limestone gorge of Beresford and Wolfscote Dales, excitedly weaving through the wooded depths of Dove Dale to Thorpe. By Wetton and Alstonefield and eastwards from the High Peak and Tissington Trails the walks in this guide explore the beauties of the high rolling plateau and the seclusion of the side dales. They deliberate upon the historic secrets of Minninglow and Roystone Grange, Harborough Rocks and Brassington, Tissington and Ashbourne.

Hartington Hall youth hostel, the ‘bee’s knees’ in terms of modern YHA accommodation (Walk 17)

What to Take

Only joy and good cheer can flow from carrying and wearing proper modern outdoor gear. Patronise dedicated outdoor shops to get the best advice. It does pay dividends. Your custom is important to them and you are likely to get one-to-one treatment and years of value from your purchases.

Into a light daypack stow some measure of weather-protective clothing. This will come to your rescue should the elements threaten to conspire by wind, rain or intense sun to spoil your outdoor adventure. (The summer of 2008 when this guide was being researched was extraordinarily wet and the author was grateful for the latest generation of waterproof trousers, enabling him to laugh in the rain!) Take along also a modest snack and a drink, which if nothing else will give you added cause to stop and soak in your surroundings all the more appreciatively. One cannot over-emphasise the value of wearing comfortable boots and woolly socks. They are your point of hard contact and the basis of your walk – happiness turning to misery on a sixpence if you get it wrong.

Even with this guide in your pocket, make a point of obtaining the relevant Ordnance Survey or Harvey map to get the bigger picture and deduce finer detail. Another piece of kit you should automatically pop into your daypack is a compass to confirm your direction of travel. Make a point of practising orientating it with the grid lines on the map to fix positions. Such things as a torch and a small first aid pack will come to your rescue should you stumble, and sun cream is important when the sun does shine, combined with a suitably wide-brimmed hat. As a bonus have a camera handy to record the visual pleasures and surprising incidents along the way (and send any you are proud of to www.markrichards.info to share with fellow walkers).

Local Services and Transport

The White Peak area is geared to the visitor and, in particular, the outdoor enthusiast, whether travelling by bike or boot. There is a good spread of tearooms and pubs, the competition ensuring the standard is universally high, and plenty of overnight accommodation. The author sampled two youth hostels (Hartington and Youlgrave) and two campsites (Birchover and Blackwell) and can heartily recommend the service provided.

In support of residents (and a bonus for the visitor) there remains a good network of bus services routed through the core villages and towns which can efficiently play into walk planning. This guide chooses to focus on circular walks, but if you leave the car behind and plan ahead, there is great scope for fascinating cross-country expeditions with the bus journeys themselves becoming a real part of the scenic pleasure. Consult the National Park website – www.peakdistrict.org – where you can also download the Peak District Bus Timetable (published in March and October) and Peak Connections guides.

Using This Guide

Even for those comparatively new to venturing into the green yonder, the walks in this guide should be logical to follow and introduce only relatively small bite-size chunks of countryside. The routes range between 3 and 10 miles long. Invariably there is scope to extend or, on occasion, shorten, but they are designed to be natural, fulfilling half-day excursions.

The 30 walks in this volume are, from tip to toe, a sweet and savoury selection. They are consistently well marked and signposted to the eternal credit of the Park Authority and particularly the Ranger Service, which forms a valuable source of information and advice for visitors and residents alike.

The guide’s vignette extracts from the Ordnance Survey maps are included to give readers a feel for the overall course of each walk, but they are no substitute for carrying and frequently referring to the relevant OS Explorer map – OL24 covers this volume.

Beacon at the corner of the Mermaid car park, set ablaze by the setting sun (Walk 2)

The aim of this guide is to help you structure your exploration of the White Peak. Once into the swing of White Peak wandering you will start to see your own logical pattern and adapt the walks to suit your own objectives and this is as it should be. There are also converted railway trackbed trails (for walkers, cyclists and horse-riders) and several specifically waymarked trans-Park trails which, with the help of public transport, may lead you to construct elongated routes of your own – linking A with B to see for yourself!