Читать книгу Beyond the Coral Sea: Travels in the Old Empires of the South-West Pacific - Michael Moran - Страница 12

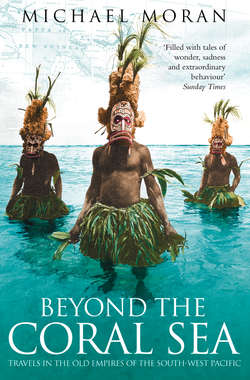

5. Too Hard a Country for Soft Drinks

ОглавлениеThe elderly ‘whiteskin’ standing on the wharf at the Alotau harbour side, casually dressed in check sports shirt and light trousers, was waiting for the St Joseph putt putt1 to tie up. I was waiting for the Orsiri banana boat to finish loading and head off for Samarai. The fresh bread delivery was delayed so I hung about smoking a rough cigarette made from tobacco rolled in newspaper. An albino Melanesian ambled past squinting against the sun, his pink skin shockingly blotched, yellow hair dazzling against the palms. Decrepit trade boats were taking on crew who sat on the stern rails, ejecting jets of scarlet into the water and calling out to their friends in passing trucks. My nose was assaulted by a peculiar mixture of fish, yeast, distillate and copra. Banana boats packed with produce and drums of diesel skated across the harbour towards the islands like hunting water spiders. The sun beat down.

‘Good morning!’ I was the picture of bonhomie.

‘Good morning, my son. Are you visiting Alotau? We don’t get many of your sort, oh no.’

I thought this was an extraordinary way to greet a stranger. He had an Irish accent and mottled complexion. All ‘whiteskins’ who have lived in the tropics for years have this wan appearance. We stood side by side rocking on our heels in a foolish colonial manner, looking at the colourful activity, glancing from time to time at the oil slick and coconut husks floating in the water below the wharf.

‘I’m the Catholic priest in Alotau … oh yes … the Catholic priest.’ He volunteered in answer to my quizzical look.

‘Ah! How long have you been here, Father?’

‘Oh yes … must be getting on for thirty years now, thirty years since I left Ireland. I’ve stopped counting, I have that.’

‘I suppose there have been a lot of changes in your time.’

‘Oh yes … murders and break-ins are increasing all the time, they’re always about, they are that. That’s right. A boat from Lae brought in a whole criminal element, it did. It’s gone now, thank goodness, together with the murdering, thieving boyos we hope … oh yes … we do hope that.’

‘I heard about that boat.’

‘Did you now. You must have your ear to the ground. Oh yes … they know where you are all the time … they’re watching all the time … oh yes … now he locks his door … yes … now he’s gone out … yes … yes … now he’s come back. He’s gone inside and locked the door … He’s turning on his light. Now he’s having a shower. They know it all and see in the dark … oh yes … they see in the dark, they can do that.’

‘Has your health stood up over the years, Father?’

‘Well, to tell you God’s truth, I’ve had the fever recently … and it laid me desperate low but I seem to be all right now … oh yes. Age creeping on now.’

More shuffling and gazing.

‘I’ve read that sorcerers and magic are still about.’

‘Oh yes … the magic and the witchcraft are strong, strong. They might be Christian but that old black magic is still there in them … it’s a terrible ting, terrible ting, terrible, terrible … Propitiate the spirits of the departed now … it’s a dark existence out here to be sure. It certainly is that.’

The St Joseph, freshly painted in yellow ochre, finally tied up at the wharf. The priest waved to some village women dressed in Victorian cotton smocks.

‘That’s my lot there … oh yes … I’ll have to leave you now. God be with you on your travels … yes … God be with you,’ and he wandered over to his flock.

The bread had arrived while I was chatting and the banana boat prepared to leave. This powerful vessel had twin seventy-five horsepower outboard motors and two plastic garden chairs. We powered out of the harbour and the cool wind brushed our faces and lifted our spirits. The rusting Taiwanese trawlers were soon left far behind as we sped along the south coast of Milne Bay towards East Cape. A young village girl carrying some shopping sat in the seat beside me. She prattled on in Pidgin to the two boys piloting the boat but they said nothing at all to me. I put my feet up – one on a carton containing an electric lawn mower and the other on a carton of several hundred tins of baked beans. The dinghy began to buck as we headed towards the open ocean and I noticed there were no life jackets. Later I was to learn that this omission is quite normal practice. I would have felt decidedly wimpish to have mentioned this in such a ‘masculine’ society. Be a man and drown or laugh as you are taken by a shark. My panama began to whip around my legs as I held it down out of the wind.

We followed the coast east for only a short time, sailing parallel to the road I had travelled only a couple of days before. The sea became rougher as we turned south towards Samarai and the Coral Sea. I felt a tremendous sense of exhilaration, my face dashed with spray, slicing through the azure water, the dark-green jungle defending the mountainous interior coming up on the right. Coconut palms, transparent green water fringing crystalline beaches, a swirl of smoke from the occasional bush hut. Young, brown, white-breasted sea eagles soared on the up-draughts, their wingspans majestically spread against the vegetation. Fragile outrigger canoes weathering the sea swell were cheered on by the boys.

The currents in China Strait are treacherous. The pattern on the surface of the water changes from seahorses whipped by the wind to smooth powerful eddies of deep blue streaming up from the abyss. The pastel outlines of numerous small islands appeared, jagged peaks lifting from valleys shaped like cauldrons. The sun broke through gunmetal clouds and burnished the sea, biblical rays that appeared to be guiding us to salvation. I realised with surprise I was soaked to the skin.

Captain John Moresby landed on Samarai from HMS Basilisk in April 1873 hoping to evade the unwelcome attentions of his ‘savage friends’. He settled down to dinner with his officers but they were followed by a hundred fighting men, who squatted quietly on the beach beside the blue water and watched the proceedings with close interest. Moresby offered them a stew made of preserved soup and potatoes, salt pork, curlew and pigeon, which, not altogether surprisingly, disgusted the warriors. The sailors unsuccessfully tried paddling canoes which resulted in capsizals, hilarious moments for all concerned. The warriors opened the officers’ shirts and stroked the white skin of their chests in wonderment and appreciation. Captain Moresby wryly named the place Dinner Islet to mark this unusually human and peaceful encounter. The local name of Samarai soon replaced the cannibalistic associations of the former.

The island appeared a deserted ghost town at first sight. The former provincial headquarters, which is an older settlement than Port Moresby, had clearly seen better days. I climbed up onto the Orsiri trading wharf to take my bearings. Ruined warehouses lined the neglected International Wharves site, warehouses gaping like skulls set on a rack, the empty interiors propped up by partitions of broken bone. Planks and beams jutted out like shattered teeth. Clumps of resentful youths were loitering around the general store and glared at me without a smile, but the women and children greeted me with friendly waves.

‘Apinun!’1

‘Apinun!’

The mown grass and coral streets (there is only one rarely used motor vehicle on Samarai) seemed like sections of an abandoned filmset. I walked between the abandoned shells of two buildings in which some boys were shouting and playing football. I hoped I was heading towards the Kinanale Guesthouse, run by Wallace Andrew, the grandson of a cannibal. Some attractive colonial houses were ranged around the perimeter of a waterlogged football field. In the sultry heat I leant exhausted against an electricity pole near a memorial obelisk before heading for a small beach in the distance. Rain trees and old flamboyants offered cooling shade.

‘Hello there!’ The voice came from a porch at the top of a flight of steps to my left. ‘Come up and have a drink!’

A tall, smiling ‘whiteskin’ wearing shorts, his legs covered in the ubiquitous small plasters, beckoned me in.

‘I’m looking for the guesthouse run by Wallace Andrew. Do you know where it is, by any chance?’

‘It’s just there!’ and he pointed to a large house partly covered in old wooden scaffolding. I had thought this structure was an abandoned building project.

‘Wallace is about somewhere, but come up for a minute.’ He disappeared inside.

I went into the sitting room and collapsed into a chair while he brought some iced water from the fridge. Furniture was clearly hard to come by on Samarai and the room had the feel of a temporary arrangement that had drifted out of control into permanence. For no good reason I imagined I could see mosquitoes everywhere. Probably the beginnings of tropical madness.

‘Hi, there. I’m Ian Poole, Manager of Orsiri Trading.’ I instinctively felt he was open and lacking in the customary consuming demons, a rare quality in the tropics, although it was a slightly mad challenge maintaining a business in this remote spot. Australians generally manage extremes with equanimity and dry humour.

‘I’m just travelling the islands. Chris Abel from Masurina told me to look you up. I’ve heard you have an encyclopaedic knowledge of the place.’

‘Well, it’s certainly interesting. Wallace knows a lot more about the local villagers and Kwato Mission, of course. He was born there.’

‘I’m surprised there are so many old buildings left. Didn’t the Australians carry out a scorched-earth policy to stop the Japanese?’

‘Yes. Unnecessary, though. The Japs buzzed the island a few times in flying boats and dropped a couple of bombs but that was it. The Aussie Administration Unit set fire to all the commercial and government places including the famous hotels. Tragic loss. You can still see the few survivors around the football pitch.’

Missionaries were the first Europeans to establish themselves in this part of Eastern Papua New Guinea. By 1878 the Reverend Samuel MacFarlane had made Samarai a head station for the London Missionary Society, but the LMS soon exchanged land on Samarai for the island of Kwato a short distance away. At the turn of the century Samarai had no wharf or jetty and goods were off-loaded from trading vessels into canoes. It was a government station, a port of entry and a ‘gazetted penal district’. Local labour was forcibly recruited here for the plantations. Copra and gold-mining dominated life, and this tropical paradise became a more important centre than Port Moresby. The town, if it could be described as such, consisted of ‘The Residency’ (a bungalow built on the only hill for the first Commissioner General, Sir Peter Scratchley, appointed by the Imperial Government in 1884 and dead from malaria within three months), the woven-grass Sub-collector’s House, the gaol (with the liquor bond store in the roof), the cemetery and Customs House, and two small stores plus a few sheds. There were no hotels or guesthouses in the early days of the 1880s, the traders living mainly on their vessels and the gold-diggers camped out in their tents.

The Europeans besieged Whitten Brothers’ premises since alcohol was dispensed from their store. The empties were hurled onto the sand from the roofed balcony. A village boy collected the bottles the next morning and counted them. Whitten then divided the number of bottles by the number of men drinking and so accounts were democratically settled. According to the entertaining reminiscences of Charles Monkton in his book Some Experiences of a New Guinea Magistrate published in 1921, men dressed mainly in striped ‘pyjamas’ or more festively in ‘turkeyred twill, worn petticoat fashion with a cotton vest’. He describes picturesque ruffians roaming the palm-fringed shore. One incorrigible known as ‘Nicholas the Greek’, after pursuing an absconder through impenetrable jungle, returned with only his head in a bag. When questioned about the missing body he laconically commented, ‘Here’s your man. I couldn’t bring the lot of him, so I’ll only take a hundred [pounds].’ Monckton also describes ‘O’Reagan the Rager’, who was ‘never sober, never washed, slept in his clothes, and at all times diffused an odour of stale drink and fermenting humanity’. The spectacular sunsets and moonlit tropical nights of Dinner Island had formed a cinematic backdrop to all types of mysterious schooners, yawls, ketches, cutters and luggers with eloquent names such as Mizpah, Ada, Hornet, Curlew and Pearl.

‘Life was pretty primitive here in those early days, I suppose.’ I wanted to draw Poole out. He obliged me at length.

‘Simple pleasures as now, I reckon. The malarial swamp was filled in by the prisoners to make a cricket field. Local people were forbidden to wear shirts in case they spread disease. They believed “the fever” came from the miasma that rose from the stagnant water. Mal aria means bad air, I think. Samarai was a deathtrap. The cemetery was always full. In fact, the fatal swamp occupied the football pitch right in front of your guesthouse. Sheep were imported from Australia and used to graze there until they were needed for meat. The residents, I think there were about a hundred and twenty in the early part of the century, played tennis, cricket and the children went swimming. Simple pleasures as I said.’

‘Sounds idyllic.’

‘There was always the demon drink. That’s a story in itself. The first hotel was called The Golden Fleece. One large room and a veranda. It was built of palm with a thatched roof. No doors or windows. Guests were expected to bring their own sheets, knives, forks and plates and sleep on the floor. Drunks would stumble in at night in hobnailed boots and fall over each other cursing and swearing.’

‘But I thought Samarai was famous for the glamour of its hotels!’

‘True, but that was later in the 1920s. There were a couple of better hotels – the largest one had two storeys and was called The Cosmopolitan. Another called The Samarai, was at one time run by a real merry widow named Flora Gofton. Missionaries had to drag the drunks into church. One called “Cheers!” during the consecration.’ I had to smile at this.

‘And the hospital?’

‘Oh, they built two hospitals and two schools – one each for Europeans and Papuans. Water was segregated as well. “Pride of race”, they called it. On moonlit nights people would go around the island by launch singing. Everybody loved the place, although it was pretty wild with drunken miners and labour recruiters.’

‘Women must’ve had a pretty rough time.’

‘Some sad stories there. Many just upped sticks and left. There was a Swede named Nielsen who worked his butt off and made a few quid. Then he married a pretty Australian girl who was a bit footloose, you know the sort. She finally pissed off and went south. Every three weeks he would paddle his dinghy out through the mangroves to meet the steamer. Dreamed she would be on it. He always dressed up to the nines to meet her, immaculate – tan boots, clean shirt, tie and white duck trousers. She always disappointed him and never arrived. He would return to Samarai cursing all women and get drunk as a sponge that night.’

‘What about married women?’

‘Spent all their time looking after ill children. Helluva life. I’ve got part of a letter here somewhere that will give you an idea.’ He fished around in a hefty file by his armchair and extracted a dog-eared photocopy. I noticed he kept scratching his legs and bare arms as did most expatriates I met in Papua New Guinea.

‘This one was written by Nell Turner, married to an officer of some sort. It’s from The Residency, used to be up on the hill, dated January 1909. She writes: “Alf is not at all well tho’ he is gaining weight this last month … Kate is a lot bigger than mother – gets bigger and fatter after each baby. Mollie had convulsions on New Year Eve and took over two hours to come out of it, was quite stupid for a couple of days after, she seems quite recovered now. Munrowd had a fit a week after Mollie, but is well again. Jean had a dose of fever but is on the mend.”’

‘Sounds drastic to me. Matter of fact my own wife is in Australia at the moment. It’s tough for women here.’ He carefully placed the letter back into his archive. ‘I hope to write a history of Samarai one day. No time of course.’

I suggested we find Wallace, so we went over to the guesthouse. I called out but there was no reply. The large room was sparsely furnished and seedy, like an old people’s home. A meal was laid out on a table under white gauze. It was dim despite the fierce sun blazing down outside.

‘Yu yah! kamap pinis!1 I had gone down to the wharf to meet you!’

A voice came from the gloomy interior at the back of the house. A patriarchal Melanesian in an immaculate white shirt emerged from a corridor limping slightly. His grey hair was carefully groomed, teeth mauled by betel, warm eyes that expressed a mixture of love and disappointment. One of his hands had been amputated midway down the forearm.

‘Got your letter. I’m Wallace Andrew.’

Ian left us. Wallace immediately sat down at a bare table and began to play a game of patience with a limp deck of cards. It was as though he needed to erect a barrier to communication as a safeguard. Clearly he had spent years of his life playing this game in lonely isolation. The skill with which he shuffled the deck and deftly dealt and gathered the cards in with the stump of his arm fascinated me.

‘I’ve come to see Samarai and Kwato.’ I pulled up a worn chair.

‘Ah, it’s so beautiful there. We’ll go together, you and I, to Kwato. Many people used to come, but there are few visitors now.’ The cards flopped softly onto the table. He scarcely noticed if the game ‘came out’ and took even less interest. Time seemed to have come to a shuddering halt. I realized with alarm that nothing was actually going to happen in the next five minutes, the next hour, for the rest of the afternoon, for my entire life if I stayed on the island for long enough. My own arrival was the main event of the week. I needed to slow down to Melanesian time. It was quiet in that room and baking hot. The ceiling fan motors had probably burnt out long ago.

‘Dinah will show you up to your room. Then come down and have lunch,’ he suddenly said.

A petite village woman with a beautiful smile gestured for me to follow her up what was almost a grand staircase. The central carpet had long since disappeared, but the unpainted wooden strip in the centre was a ghostly reminder of some past attempt at luxury. We took the right flight of the staircase and passed through two bare rooms with flaking paint. Broken lampshades, mattresses and lumber lay abandoned on the floor in a corner. Her bare feet noiselessly brushed the cracked lino. A long veranda opened off a landing, but the bleached scaffolding hid any view. She pushed open the door to No. 8, a large room furnished with a double bed, a single bed, a dressing table, a wardrobe and a fan. It was clean and comfortable with screened windows against mosquitoes. French doors opened onto the veranda. I looked through the maze of planks over the former swamp to the few colonial buildings that had survived the destruction of the war.

‘You share the bathroom and toilet,’ she said in excellent English and showed me the most basic of conveniences. I noticed a sign in red letters under a sheet of discoloured plastic on the wall of the shower: ‘For hot water pull string.’

Dinah smiled again and disappeared. A corridor led out to what I thought was a rear entrance, but I found that the stairs had been removed and a twenty-foot drop into empty space yawned below. In a shed I could see a wrecked dinghy. I wandered back into the stifling room and sat on the bed. Glancing up I caught sight of my reflection in the glass. A crumpled traveller, sweating heavily, weighed down with notebooks and maps, wearing a sand-coloured colonial shirt, a planter panama and blue suede boots. Overdressed for the occasion I thought. I noticed there were no locks to the door of room No. 8 as I went down to lunch.

‘Where were you born, Wallace?’ I had poured myself some livid green cordial and was helping myself from a platter of reef fish and bananas.

‘On Logea Island, near Kwato.’

‘Really? Some people feel that Kwato was where the nation of Papua New Guinea began.’

‘Certainly it was.’

The legendary island mission station of Kwato gives rise to strong passions and controversial opinions. Many of the most distinguished people in public life in the national government attended this mission school. Wallace often lapsed in and out of pidgin which confused me on occasion. Fervent Christianity was obvious in every sentence.

‘The people of Milne Bay and the islands wantim Word of God, very much they wantim. Charles Abel tried to make a new Papuan society that was Christian and educated for working. He taught us boat-building and metalwork. Mainly discipline and concentration he knock it in their heads. Young people don’t want these things now.’ He dealt the cards to himself all the time he spoke, cultivating chance. Dinah was clearing away the remains of the lunch.

‘Respect for custom certainly seems to be passing away.’

‘Gone. Gone now. Young people are too lazy to keep kastom alive. Prayer is the answer to all problems, Michael. You must pray. Even when they stole my television and wrecked my boat I prayed.’ He began to hum a hymn tune I vaguely recognised.

‘Did you get it back?’

‘No. God didn’t want me to watch any more television. It was a sign. I read and write more now.’ His fatalism appeared to be the final tremors of a departing soul.

‘Is anyone else staying here, Wallace?’

‘Yes. Two government ministers. The Prime Minister has stayed here. The High Commissioner in London, Sir Kina Bona, he stayed here. They all know me. We had hundreds at a celebration not long ago. I built a dancing and picnic area beside the guesthouse. Did you see it? That was before the Englishman betrayed me.’ He had stopped the mindless card-dealing and actually looked at me, animated yet with traces of anger.

‘Who was that? What did he do?’

‘Not now. You go out and look at our beautiful island. We’ll talk tonight.’

‘Fine. I’ll have a look at your dancing area.’

‘Ah, yes. Do that. Not many come here now, but in the future we’ll once more have many people …’ His voice trailed away as if he had lost confidence in the remainder of the sentence.

‘I tried to have a shower but there was no water.’

‘No, that’s right. You must tell us first and then we will turn on the pump. Guests usually shower after meals.’

‘I see. Well, I’m going now. See you later on.’

‘All right. Will you come up to the hospital with me sometime? I need some more tablets. Arthritis they say it is.’ He drifted in and out of this world, bolstering himself with prayer and medicine. I dragged the heavy fly-door open and walked out into the fiery furnace of Samarai.

A coral path shaded by coconut palms and pines encircles the island. It is known as Campbell’s Walk after the Resident Magistrate who constructed it in the early 1900s using local labour from the prison. The transparency of the porcelain-blue water is transformed to a deeper cobalt as it reaches down China Strait and out towards the impenetrable mainland and pearly lips of Milne Bay. Small coves with upturned canoes invite fishermen to dream on the rocks. Fibro shacks nestle into the sides of slight hillocks waiting to be consumed by the exuberant palms, bananas, ferns, frangipani and hibiscus. The sound of an electric train instinctively caused me to search the horizon until common sense prevailed and I realised it was the sighing of the pines on the island of Sariba. Two women were cooking over open fires in a kitchen hut adjacent to a narrow beach where a gleaming new dinghy with outboard motor was knocking on the tide. The picturesque schooners and yawls, sails bellying in the wind, carving like swift blades through the currents, have long since disappeared.

I had been walking for only fifteen minutes and was already halfway around the island. One of the most distinguished visitors to Samarai was the anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski. He was delayed here in November 1917 while waiting for the cutter-rigged launch Ithaca, which would take him to the Trobriand Islands. His favourite occupation on this walk was to read Swinburne and write his private diary in Polish. It revealed him as a man who had embarked upon a profoundly personal quest.

Malinowski was born in Kraków, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia in partitioned Poland in 1884. The family would spend part of each year in the Tatra mountains in the Polish summer capital, Zakopane, a resort which became a haven for artists and intellectuals. Around 1904 he read Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, a vast collection of myths and magic from around the world, which inspired him to become an anthropologist and writer. Despite frail health he studied mathematics and physics, being awarded the highest academic honours in the Hapsburg Empire – sub auspiciis Imperatoris1 – when he graduated in philosophy from the Jagiellonian University of Kraków in 1908. The deputy to Emperor Franz Josef personally presented him with a gold-and-diamond cluster ring at an opulent award ceremony in Kraków. In 1910 he moved to London where he began anthropological studies as a research student at the London School of Economics. He met and corresponded with eminent anthropologists at Cambridge, became a staunch Anglophile and is generally considered to have created the modern subject of British social anthropology.

By 1914 he was in Australia at the outbreak of the Great War. Although an Austrian subject and technically an ‘enemy’, he was given financial support to proceed with his work in New Guinea, first at Port Moresby and then on the island of Mailu. He also made two long trips to the Trobriand Islands from 1915 to 1918 where he followed the example set by the great Russian pioneering ‘ethnologist’, Nikolai Miklouho-Maclay, and formally introduced the concept of extended contact and methodological fieldwork into anthropology. The complex rituals of yam cultivation, the kula trading ring and, most notoriously, the liberated sexual practices of the Trobriand islanders, gave rise to a series of remarkable publications. His works became seminal studies of their kind, controlled, objective, classical and charming accounts of remote peoples. But his private diaries, written mainly in Polish,1 reveal a more complex figure, a man riven by doubt and boredom, a hypochondriac besieged by dreams and fantasies, a puritan wrestling lecherous demons nightly under the mosquito net. At a particularly low point he wrote, ‘On the whole my feelings towards the natives are decidedly leaning towards, “Exterminate the brutes.”’2 They reveal a man who had embarked on a painful journey of self-revelation. This contradictory character read novels of contained passion such as Vilette, and Tess of the d’Urbervilles, classical French works such as Phedre and the rhapsodic Lettres Persanes, even Thackeray’s Vanity Fair in the midst of a Trobriand pagan paradise. On bad days, unable to work, he would leaf through the naughty caricatures in old copies of the French magazine, La Vie Parisienne.

Constructively sublimating his eroticism was difficult. He became infatuated with the owner of The Samarai Hotel, the soon-to-be war widow Flora Gofton, and accused himself of libidinous thoughts:

… on the one hand I write sincere passionate letters to Rozia [his fiancée Elsie Masson], and at the same time am thinking of dirty things à la Casanova.

He felt he was betraying the ‘sacramental love’ of this nurse from Melbourne. In his mind he undressed and fondled the wife of the island doctor, calculating how long it would take him to persuade her into bed. He punished himself with work and exercise. Urging himself to ‘stop chasing skirts’, he cultivated a solitary passion for making tortoiseshell combs for Elsie, spending hours at this odd task, accusing himself at one point of ‘turtleshell mania’. His controversial and explicit work The Sexual Life of Savages in Northwestern Melanesia was published in 1929 with a preface by the sexologist Havelock Ellis. Not altogether surprisingly, it celebrates the magic of pagan love free of Christian guilt.

Despite his scientific training he had a creative temperament, beset by the demons of sensual temptation and metaphysical alienation:

… I have got the tendency to morbid exaggeration … There is a craving in me for the abnormal, the sensational, the queer …

In his diary he wrote descriptions of the Samarai landscape that possess the intensity and heightened feelings of German Expressionist painting:

The evening before: the poisonous verdigris of Sariba lies in the sea, the colours of blazing or phosphorescent magenta with here and there pools of cold blue reflecting pink clouds and the electric green or Saxe-blue sky … the hills shimmering with deep purples and intense cobalt of copper ore … clouds blazing with intense oranges, ochres and pinks.

He wrestled with language and culture like his compatriot and friend Joseph Conrad, a similarly-displaced Pole. Some commentators spoke of him, rather inaccurately, as the Conrad of anthropology. This he never was, possessing more of the Nabokovian ‘precision of poetry and intuition of science’, qualities the great enchanter impressed on his literature students at Cornell. But the prose of the diary, written partly in the Trobriand Islands, does share similar unsettling qualities to those we find in Conrad’s tale Heart of Darkness set in the Congo. Both writers pressure language to its limits. Malinowski was seeking a cultural truth, the resolution of an identity crisis.

‘Bronio’ felt that islands symbolised the imprisonment of existence, yet, ‘At Samarai I felt at home, en pays de connaissance [in the world of knowledge],’ he writes. His fastidious nature was repelled by what he considered the inhospitable, drunken and wretched representatives of European humanity he found on Samarai, how they contrasted so depressingly with the natural beauty surrounding him. The ‘part-civilised’ local villagers he found there offended him equally. He would compulsively circle the island on this path like a caged panther. He sometimes felt he was merely exchanging the prison of self for the prison of cultural research. Yet Malinowski redefined the role of the ethnologist, his work expressing a romantic love for non-European cultures. Here was a man driven to seek his own philosophical nirvana. He subjected his own psyche to as close an objective scrutiny as the Trobriand villagers he studied. One of the great journeys of the modern European mind began on this tiny island of Samarai in 1914.

Campbell’s Walk continued along the tropic shore, past rocks defaced by graffiti at the most easterly point but giving way to views of enigmatic Logea island shaped like an oriental hat, and chains of islets married to the sea by golden rings of sand. Clumps of hibiscus with miniature flowers suspended like drops of blood grew abundantly. Arching over the water, a strangely-shaped frangipani tree emerged from a wall, branches loaded with yellow and cream blossom, a canoe silently passing beneath. Almost hidden among the palms were the police station and the modest hospital, a moloch for patients in the early colonial days.

The heat was monstrous. I envied the village boys swimming among the tropical fish in the crystal water. I leant on a broken rail at the end of the wharf.

‘Those two are my sons,’ a voice behind me said.

I turned to see a tall, elderly ‘whiteskin’ in a baseball cap. The ubiquitous shorts and plasters decorated his legs, flip-flops on leathery feet, but it was the fathomless melancholy in his eyes that struck me. They were the bloodshot eyes of a hounded man given over to alcohol and grief. The lower lids drooped to catch his many tears.

‘Oh! They seem pretty happy. Wish I was a bit younger.’ I smiled pleasantly.

‘Well, I buried my wife a few days ago in the Trobriands. On Kitava. Died of cancer.’

‘I’m terribly sorry.’

‘We took her by boat. That’s mine over there. The Ladua. She was built on Rossel Island in the Louisiades.’ I glanced over at an attractive, wooden trade boat painted ochre and grey.

‘Why didn’t you bury her here on Samarai?’

‘I can see you haven’t been here long! Her soul must go to Tuma, the erotic paradise in the Trobriands where departed spirits dwell. It’s a pláce where you stay beautiful and there’s no old age. You might call it Heaven. You can hear the spirits crying there at night. It’s the mirror of the world.’ People so rarely speak in this way I lapsed into silence for a time, turning over these poetic images.

‘Is sorcery still strong?’

‘It absolutely rules the lives of everyone living on Samarai, particularly the women! Everything is explained by sorcery, particularly losses at sea – people taken by sharks or crocodiles. Dinghies often sink in the savage currents. We lost six drowned over there a few weeks ago, and four over here the other day. They try to take the boats as far as Port Moresby!’

I reflected grimly that all my travels through these infested waters would be without a life jacket or radio.

‘There’s a launch pad for yoyova just along the path. Did you see it?’

‘No. What are yoyova? Strange word.’

‘They’re the flying witches. They spread destruction and flame from their … well, you know! They can change shape into birds or flying-foxes, even appear like a falling star or fire-fly.’

‘But they aren’t real, surely. What’s this launch pad look like?’

‘A frangipani tree sticks out from the wall over the sea. It’s an odd shape. You can’t miss it.’

‘Yes! I did see it.’

‘They represent the malevolent magic of women, my boy. You must’ve experienced that. They’re real women all right. Some have sex with tauva’u, those malicious beings who bring epidemics.’

‘Yes, but what do they do exactly? How do they catch you?’

‘They pounce from a high place and rip out your entrails, eyes and tongue. They snap your bones then they devour the rest of your corpse.’

Those inflamed, leaden eyes might well have witnessed such ghoulish instincts in action.

‘When does this happen?’

‘Usually when there’s a storm. If you smell shit when you’re fishing out at sea, watch out! Then the flying witches will attack by the squadron! They stink!’ he laughed out loud, but without conviction.

‘They’re objects of real terror to these people. It’s no joke because their powers are inherited, carried in their belly. Sometimes the spirit leaves them when they’re asleep and goes marauding.’

I tried to imagine a world where such beings were an everyday part of consciousness. The books of J. R. R. Tolkien approached such a phantasmagoria, but his cruelty was of a different order.

‘Sorcerers don’t have the power they did in the old days!’ and he looked dreamily out to sea.

The boys had begun diving for pebbles and shells.

‘Have you lived here long?’

‘Only about sixty years. I came here when I was five.’

‘Sixty years on tiny Samarai! I think I would have gone mad.’

‘Well, I did. I live over there now. On Ebuma.’

He pointed to a perfect tropical islet surrounded by glittering sand lying a couple of miles offshore.

‘It belongs to the Prime Minister. I’m just the caretaker. My name’s Ernie, by the way.’

I introduced myself … ‘Ebuma looks like everybody’s dream island.’

‘Why don’t you come over for a few weeks? We could talk. I could show you the fishing rats. They come down to the shore at night and dangle their tails in the water as bait. Small crabs catch hold and they whip it quickly round to their mouth and fasten onto the crab. Munch, munch!’

‘You’re having me on, Ernie!’

‘There are strange things around here all right. If you see a swordfish leaping out of the water and going crazy, they have a borer in the brain.’

‘What the hell is that?’

‘A sort of parasite drills into the sword and works its way up the shaft into the brain. The fish goes mad.’

‘What a place! Look, Ernie, I’m going to Kwato tomorrow, so I might call in on the way back.’

‘It’s up to you.’

I could not quite leave this mine of information without a last question.

‘A lot of interesting people came through Samarai, didn’t they? Malinowski, for instance.’

‘Oh, him. You know he used to take opium while he was on the Trobriands? Probably did here too. Hancock, was it Hancock? Can’t remember. Anyway, old Hancock told me about it. He was a little boy when the great man came here. Malinowski criticised him as being a spoilt brat in the famous diary. Payback.’ He chuckled.

‘Come over and see me for a couple of months. We can just eat and drink there … on the beach. I’m working on another boat at the slipway just over there. You could help. Want to earn a few kina?’1

A boy of about ten was running about behaving strangely, banging the walls of the warehouse with his head, laughing manically and fighting off a group of teenage tormentors. He seemed to have no control over his muscles and flopped about like a rag doll.

‘He’s a bit simple,’ Ernie answered my enquiring glance. Boys were leaping into the water in an endless circle.

‘May see you tomorrow then. Come over for a month.’ He wandered away towards the Ladua.

I was sitting on the edge of the wharf when suddenly I was struck from behind by the flailing fists of the disabled boy. He seemed to have gone completely mad and was making the constricted sounds many damaged people make. It became quite painful and I began to slip towards the water. Some of the local boys rescued me and used the incident to give him another beating. He disappeared round the corner of a shed squealing like an animal.

I crumpled in the shade against the gnarled bole of an ancient rosewood growing near a tiny beach. Fragile canoes with delicately lashed outriggers were drawn up amidst scattered coconuts stranded by the tide, the fibre of the husks trembling in the breeze. Women were leaving the market with bundles and launching their canoes to paddle to nearby hamlets. I drifted off to sleep under a blazing copper sky only to be woken by a lizard crawling down my neck. A mangy dog began timidly to sniff my boot as dusk softly enfolded the island in the wings of a giant moth.

The grass-paved street that led back to the guesthouse was dusted with pink and white frangipani rouged by the last light, the pink trunks of coconut palms leaning over a darkening sea. The lonely bell from the Anglican church marked the hour. Wallace was seated on his usual perch by the table playing patience.

‘So, you’re back. I thought you’d been eaten!’ and he laughed wickedly.

‘No, but I almost ended up under the wharf. That disabled boy tried to push me in.’

‘Oh, he’s harmless, a sweet child really. Tomorrow you go to Kwato. The pastor is coming in the morning to take you over.’

‘Great. Look, I’ve bought a few beers, Wallace. Let’s have one and you can tell me about that Englishman.’

‘Oh, him! Not much to tell.’ He grimaced as if I had prodded a painful injury.

‘He came to Samarai like they all do for a few days, but stayed on. He decided we could restore the guesthouse and went back to England to get the money. Work began and the scaffolding was put up. I built a dancing area in the traditional style.’

‘Yes, I saw it. Beautiful local carving on the posts and boards under the roof.’

‘Beautiful, yes. But I only used it once. He was an alcoholic and ran up debts everywhere.’

‘I had an Irish business partner like that. He drank all the profits.’

‘Well, then he left, disappeared into thin air taking what was left of the money with him. I had huge bills to pay. Electricity, workmen. It broke me.’ I began to understand why the whole building was surrounded by old, bleached scaffolding. Time had stopped for Wallace as it had for Mrs Havisham.

‘Did you tell the police?’ The moment I asked the question I realised it was ridiculous out here.

‘The police? They aren’t interested in things like that.’

‘Yes, but …’

‘He’s being sought in London. He’s thought to be in Thailand.’ The story had the faded, melancholic glamour of a sepia print.

‘He sounds a typical predator. Islands attract them.’

Dinah was preparing dinner and the table had been set with more bright green cordial and chicken, taro and pineapple. I poured a glass of pure, chilled rainwater.

‘Is there any local music?’ Mercifully, I had not heard any recorded music in the villages of East Cape, just distant garamut1 drumming. The silence was inspiring.

‘Oh, yes! Music! That’s what I should be playing during the dinner.’

Depression had caused him to forget the past pleasures of hosting guests. Standards had slipped following the Englishman’s betrayal years ago.

‘My daughter is a singer. She’s made lots of tapes. I’ll get the recorder.’

He returned with an old recorder that had suffered the ravages of high humidity. The volume was either deafening or scarcely a whisper. Only one speaker was working. The songs were commercial and South Pacific in flavour, but professionally produced. The voice was very musical.

‘She calls herself “Salima”, which in Suau language means “canoe float”.’

‘Does she live on Samarai?’

‘No. She’s in Port Moresby now. All the young people leave the island to find work. My wife left too.’

Again he appeared to be wrestling with terrible dejection and unseen demons. The light went out of his eyes. He returned to playing patience. I battled with the volume control, not wishing to destroy the silence of the island night.

I had almost finished dinner when the two government officials returned from their seminar. They nodded towards me and padded upstairs. I had noticed with surprise their tiny travelling cases on the chairs of their open rooms. They rapidly caught up to my stage of dinner and introduced themselves as Napoleon and Noah. One was from the Sepik, the other from Morobe Province.

‘What’s the subject of your seminar to the councillors?’

‘Standing Orders. We need to explain the basis of the Westminster parliamentary procedure.’

‘My goodness, that must be quite a task.’

They glanced at each other suspiciously, sensing criticism.

‘They’re intelligent men. Serious men. The problem is just one of language. You know there are over eight hundred languages in our country. Explaining the concepts behind the English procedure is most difficult. Old English is a strange language for us. Standing Orders are supposed to make parliamentary business easier but in our culture … more difficult … some concepts mean nothing to these people even in Tok Pisin. Independence came before we understood how the system worked.’

They both looked dark and fierce with an almost excessive masculinity, as if it was my fault, then they smiled. Such extremes.

‘We’re having a party to celebrate the end of our mission tomorrow night at the Women’s House on the hill. You’re invited. And you, too, of course, Wallace!’

He was gathering in the flaccid cards as he thanked them, pleasure struggling up to the surface. The officials rose quite suddenly from the table and headed off to the evening session at the hall. Another hand of cards fluttered down. Wallace turned to me.

‘They always stay here, the ministers. Soon I will redecorate the entire hotel.’

He looked around the flyblown walls, the stump of his arm more than symbolic over the cards.

‘I plan a stylish refurbishment here. God will bring the cruise ships. Thousands of tourists will visit Samarai. You’re just the first of a great wave.’

I switched off his daughter’s music. Mass tourism on the scale of Fiji or Vanuatu is an impossible, even undesirable dream on Samarai. The situation seemed ineffably melancholic.

‘I’m sure you’re right. Well, I think I might go to bed, Wallace. Could you switch on the water pump?’

‘The pastor will be here in the morning. Everything will be fine.’ His voice trailed away as I climbed the bare stairs.

The air in the bedroom was hot and thick. Garish streetlamps lit the window covered by a thin curtain printed with a tropical landscape hung upside down. I switched on the fan and went for a shower. Huge cockroaches crawled up from the drain but fled as the water fell. I pulled the string that promised hot water but with no result. A blessed coolness bathed me, the effect remaining for a full two minutes. I was slightly worried about being unable to lock the door and decided to sleep with my passport and wallet under my pillow.

I had felt insecure about my personal safety and possessions ever since my arrival in Papua New Guinea. There is something in the air that combines with the menacing expression in the male Melanesian face that is unsettling to a European. The dark and brooding sensibility of the men in particular, creates an ever-present feeling of threat. I felt my presence was tolerated but deeply resented. Smiles shielded a deeper animosity; an ancient impenetrable psyche lay behind those dark eyes. I was not wanted here, the past was resented and there was jealousy of my imagined riches. Covetous glances settled on my belongings. Serious health risks could not be avoided. So came upon me the first temptation to abandon the whole enterprise and return to Sydney. This was to become a common feeling I was forced to fight. Only the idyllic beauty of the islands, the complex cultures and the occasional warm personality kept me travelling. Wallace was a truly good man, but what had it brought him? Theft, vandalism and betrayal. I lay on the bed and stared at the fly-spotted ceiling. The lonely Anglican bell marked the passage of European time. A solitary bird was singing, a species that sings after sunset for the entire night.

Whispers below my window woke me. I could see some youths had clustered around the marble obelisk and were looking up at my window and pointing. I remembered the Catholic priest at Alotau. ‘They know where you are, if you’re asleep, he hasn’t locked his door … oh yes.’ They wandered away at length and the memorial was bathed in moonlight.

The story of how this obelisk came to be erected is one of the legendary tales of this Province. It began with the cannibalistic murder in 1901 of one of the first missionaries to come to Eastern New Guinea, the Scotsman, the Reverend James Chalmers. He was a friend of Robert Louis Stevenson who described him as ‘an heroic card … a big, stout, wildish-looking man as restless as a volcano and as subject to eruptions’. He was as much an explorer and adventurer as a missionary. The title of his book Work and Adventure in New Guinea (1885) describes his attitude to missionary activity succinctly. On one occasion tracing a journey on a map in a village hut, he noticed that drops of liquid had begun to fall from a bulky package lodged in the roof. Grandmother’s remains were being dried by her grandson. In many parts of the country the corpse was not buried immediately after death but retained by the family, placed on a platform outside the hut, perhaps smoked and stored or the remains given to the children to play with. In this way the relatives clung to the spirit of the dead for some time after the passing of the body. ‘It quite spoiled our dinner,’ Chalmers laconically commented later.

His book is full of bizarre cultural descriptions. One of the most celebrated is that of the ‘man-catcher’. This was a hoop of rattan cane attached to a bamboo pole that concealed a spike. The hoop was slipped over the head or body of the fleeing victim and then suddenly jerked tight. The spike would penetrate the base of the skull or spine, neatly severing the spinal cord. Ernie had told me during our talk on the wharf that Chalmers carried a Bible under one arm and a shotgun under the other as the instruments of conversion. Certainly not your average missionary, more an aggressive soldier of Christ unwittingly preparing the ground for the arrival of the colonial service.

The charismatic Chalmers was known as ‘Tamate’ by the people of Rarotonga. He was a fine figure of a Victorian gentleman and possessed a head as noble as that of the composer Brahms. Both his formidable wives succumbed to malaria. He writes of having to exhibit his chest to the warriors on numerous occasions each day. One friendly chief offered his wife a piece of human breast at a feast, declaring it a highly-prized delicacy. Chalmers wryly observed that this was the end of his chest exhibitions in that part of the country.

In 1901 the London Missionary Society schooner Niue set sail along the coast of the Gulf of Papua from Daru. It anchored off the ironically named Risk Point on Goaribari Island near the mouth of the River Omati. This area was well known as one of the most dangerous parts of New Guinea, an area of torrid mudflats and swamp crawling with tiny crabs and fierce cannibals. Early on the morning of 8 April some warriors with faces and shaven heads painted scarlet, their eyes ringed in black, paddled out to the vessel in a fleet of canoes and persuaded a landing party to come ashore. The unarmed Chalmers and his young and inexperienced assistant Oliver Tomkins, together with ten mission students from Kiwai Island and a tribal chief, landed from the whaleboat in a creek close to the village of Dopima. Chalmers had attempted to convince Tomkins to stay on board but the intrepid youth would have none of it. The warriors trembled and giggled with excitement, their cassowary plumes and long tails of grass swishing and shivering in anticipation. The Europeans entered the enormous dubu or men’s longhouse, all six hundred feet of it, and greeted the occupants. The air of the long, gloomy tube was thick with suffocating smoke and heavy with acrid odours. Rows of enemy skulls by the hundreds were arranged on shelves and racks, some fixed to macabre carved figures hanging from the roof.

The visitors were immediately struck from behind with stone clubs, and fell senseless to the floor. Tomkins managed to escape as far as the beach but was brought down with spears. This was the signal for a general massacre. Chalmers was stabbed with a cassowary dagger and his head was immediately cut off. Tomkins and the rest of the party of young mission boys suffered the same fate. The bodies were cut up and the pieces given to the women to cook. The flesh was mixed with sago to produce a monstrous stew and eaten the same day. The heads were divided among various individuals and quickly concealed from view. Ironically, the party who had expected to return to the schooner for breakfast had unexpectedly become breakfast. The Niue meanwhile had been boarded by a canoe raiding party and looted. The Captain managed to get under way and brought the grisly news of the slaughter to the wretched settlement of Daru.

After twenty-five years working among the ‘skull-hunters’, it is surprising that Chalmers allowed himself to be fooled. He was famous for possessing an infallible instinct for reading primitive moods and knowing when to leave. The precise reason for the butchery is unknown but there is speculation that he insisted on visiting in the middle of a ceremony that was forbidden to outsiders.

That this was an unprovoked cannibal murder rather than a revenge killing was clear. A punitive expedition was mounted three weeks later from Port Moresby. When the Government steam-yacht Merrie England (a most versatile vessel that reportedly could ‘go anywhere and do anything’) finally left Goaribari, some twenty-four warriors lay dead, many wounded and all the sacred men’s longhouses on fire. But the heads of Chalmers and Oliver had not yet been recovered.

A year or so later, a young lawyer, Christopher Robinson, was appointed Chief Justice and was acting as Governor of the Possession. He decided to go to Goaribari in one of the pretty gilded cabins of the steamer, retrieve the heads and capture the murderers for trial. He had learned that in the matter of identification of skulls, those that had artificial noses attached were from people who had died from natural causes; those skulls without noses had been killed, the noses bitten off by the killers. As fate had it, the party he assembled were chronically inexperienced in dealing with villagers or had only recently arrived in New Guinea.

In April 1903 the Merrie England once more anchored off the cannibal shores of Goaribari. Some of the highly excitable local people were enticed aboard from their canoes with trinkets and trade goods. The murderers were known to be among them. The ‘grand plan’ was that the constabulary would grab them upon a given signal. The plan went horribly wrong. Wild fights erupted all over the deck. The red-painted warriors remaining in the canoes attacked the ship with arrows which drew rifle fire from anyone on board who could lift a weapon. Nearly all lost control in the ensuing panic and blazed away at everything that moved on the water. One, a letter copyist, collapsed in a fit of shrieking hysterics at the sight of a man being shot. An unknown number of the inhabitants of Goaribari were killed.

The facts of the case were instantly sensationalised and exaggerated by an Australian press starved for scandal. The missionary from Kwato, Charles Abel, demanded a Royal Commission to investigate the circumstances of the reprisal raid. Robinson was vilified with sulphuric slander and offered up for immolation. The innocent steamer Merrie England was absurdly compared to the infamous Australian ‘black-birder’,1 the slaving brig Karl, owned by the Irish physician, Dr James Murray. Robinson was summoned to Sydney and a junior magistrate appointed in his place as Governor. Like Timon of Athens he was now abandoned by all his false friends. He took the only course open to a gentleman of honour in those days. While the occupants of Government House in Port Moresby were peacefully sleeping, he wrote his account of the incident, accepting full responsibility for the actions at Goaribari. He then took his revolver, walked out to the base of the flagstaff in the moonlight and blew out his brains over the withered grass. He was thirty-two.

The marble obelisk, ghostly in the silver moonlight below my window at Samarai, commemorates this sad saga. Part of the inscription reads:

His aim was to make New Guinea a good country for white men. This stone was set up by the men of New Guinea in recognition of the services of a man, who was as well meaning as he was unfortunate, and as kindly as he was courageous.

The monument is now considered to be politically incorrect and the plan is to tear it down.

1Pidgin for ‘launch’.

1‘Good afternoon!’

1‘There you are!’

1This Latin phrase means ‘Under the Emperor’s Seal’. It was the highest academic honour in the Hapsburg Empire and only one or two were awarded in any one year. The recipient was given a jewelled gold ring carrying the Emperor’s seal which was conferred at a grand ceremony by a representative of the Emperor. Malinowski lost his ring.

1On the inside front cover of the black notebook he inscribed in blue-grey ink: ‘A diary in the strict sense of the term,’ and immediately beneath: ‘Day by day without exception I shall record the events of my life in chronological order. Every day an account of the preceding: a mirror of the events, a moral evaluation, location of the mainsprings of my life, a plan for the next day.’ And beneath that: ‘The overall plan depends above all on my state of health. At present, if I am strong enough, I must devote myself to my work, to being faithful to my fiancée, and to the goal of adding depth to my life as well as to my work.’ The first entry, on page one, is ‘Samarai 10.11.17’ (quoted from Michael W. Young’s as yet unpublished biography of Malinowski).

2Italics written in English and taken from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

1The currency in use in Papua New Guinea. At current rates (2002), 1 kina equals about 25 pence.

1The garamut is a type of slit drum commonly used in the islands. The carrying power of this simple instrument is extraordinary in the still air of tropical nights.

1A ‘black-birder’ was a slave ship or the captain of one that forcibly abducted men from island villages for labour on the Queensland or Melanesian plantations. Dr Murray and his brig, the Karl, were notorious in South Pacific waters for sensational cruelty and murder in their pursuit of profit through slavery.