Читать книгу Here We Go Gathering Cups In May - Nicky Allt - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Siege of Rome

ОглавлениеIn 1944 a young Bob Paisley rode into Rome on a tank when the city was liberated. In ancient history it was the Etruscans and the Gauls who flooded in and took over. In the year AD 1977 it was the turn of the Scousers. To say that the Romans were worried is an understatement. English clubs’ rep abroad was well dodgy. Tottenham fans had rioted in Rotterdam at the ’74 UEFA final, and Leeds fans went berserk and wrecked the Parc des Princes in Paris during the ’75 European Cup, both with only a fraction of the fans we had in Rome. The I-ties were so paranoid about the situation that they had 4000 bizzies on duty that day, including crack sections of the Carabinieri (military bizzies) plus riot squads and anti-terror units. It was the biggest-ever police operation in Italy for a footy match. The Olympic Stadium owners weren’t taking any chances either. They actually took out extra insurance cover of seventy thousand pounds, in case we ransacked the stadium. I suppose the hysteria was understandable, but if they’d have done their homework, they could have all sat back with a big fat Italian cigar. Because we weren’t English; we were Scousers … you know the score.

‘Oh, we’re the greatest team in Europe and we’re here in Italy … Italy … Italy’ was the song that greeted Rome as we came out the station. The sun was now on about gas mark seven. The heat hit us like a flame-thrower. I reckon I can honestly say that not one of the 26,000 had sun lotion. Nobody went abroad on holidays back then, and at home the sun was like a UFO, so suncream was unheard of. Some beaut on the train was telling everyone that if it got too hot, the best thing to use was olive oil. The soft bastard must’ve ended up barbecued. Buses were laid on to take us through the city, but we headed straight for a cafe over the road and sat under a parasol. Jimmy had the Italian waiter fucked: ‘D’yer sell bitter, mate?’ The waiter just stood there.

Wardy’s attempt sounded African, like Idi Amin. ‘Bitter … beer,’ he said. The waiter came back with three lagers. Wardy raised a toast to Rome … grinning, with a bottle in his hand. We savoured the moment, watching hundreds of Reds pour out the station; dozens had criss-cross red marks on their backs from the luggage racks.

The I-ties had warned us all via the Echo to beware of pickpockets, Rome being the dipping capital of Europe. It was a big talking point amongst Reds. The bullshitters were in their element. One lying bastard by the cafe said that 200 people off our train were dipped as they came out the station. ‘D’yer mean by the same fella?’ Wardy said. Everyone absorbed the warnings, but by the time we got to Rome it’d become a source of pisstaking. The main prank on the day was sliding your hand into one of your mate’s pockets and watching his paranoid reaction. I had Jimmy spinning round like a gunslinger all day. If the dippers were rubbing their thieving hands waiting for 26,000 middle-class English tourists (the only folk who travelled those days) then they must’ve got a big shock when they saw the rough, unwashed hordes emerge from the station. We looked more destitute than them. One of the best shouts was from a white-haired old Scouser sitting by us outside the cafe. He said, ‘The coppers have just arrested a dipper. They emptied his pockets and found 150 giros and 200 sick notes.’

After a few cold beers and an oily ham cob we moseyed, not knowing or caring where we were going. We followed what sounded like a fox hunt to a street around the corner. It could’ve been any street in Liverpool. Hundreds were sitting outside bars, drinking and reading Tuesday night’s Echo. They were mainly from the airborne battalions that’d been winging in all night and morning blowing little trumpets they’d bought at Speke airport for a quid. A total squadron of sixty-eight planes had touched down since the weekend – the biggest airborne assault on Europe since the battle of Arnhem. For 99 per cent of Red passengers it was their first-ever flight. Some loved it, some hated it and some were so arse-holed that they probably still don’t remember it. A gang of lads told us about a couple of stowaways who hid on their plane at Speke. They almost pulled it off but were smoked out after being sussed sneaking across the runway.

Fleets of orange trams kept passing with dozens of Reds hanging off them holding up fat green bottles of ale and singing the ‘Arrivederci, Roma’ song. It was only early, but already our heads were starting to get fuzzy. We wised up and decided to shoot back to the station for a swill, then try and see a few sights: Colosseum, Vatican, Trevi Fountain and all that lark.

I got some weird looks from locals in the station bogs when I started using the bandage on me hand as a toothbrush. The bandage was decomposing by the hour. It had ale and orange-juice stains on it and was coming in handy as a sweatband. There were about fifteen toilet cubicles in there. They were the first bogs we’d ever seen with just a hole in the floor. We couldn’t believe it. Jimmy was pushing doors open saying, ‘Where’s the pans?’ I wouldn’t have minded, but the holes in the floor were tiny. We just had to get on with it. Quite a few Scousers were dotted about in the other cubicles. There was loads of laughing and shouting going on. ‘This is like The Golden Shot’ got a laugh. Someone came back with ‘Y’mean The Golden Shit’. Wardy got a giggle with ‘I’ve just gone in off the post’. Jimmy’s voice was unmistakable: ‘I think I’ve just hit the fuckin’ corner flag.’ It was a good grin but without doubt the most awkward, uncomfortable Barry White I’ve ever taken, especially with my bandaged right hand out of use. I was like a fuckin’ contortionist.

The phone boxes only took special coins with grooves cut into them. Jimmy’s translation was quality: ‘All right, mate. Have y’got any of them phone coin things … lire for the blower?’ It descended into sign language, with Jimmy holding an imaginary phone to his ear saying, ‘Hello … hello.’ He got two coins, and we headed for a phone box. Jimmy put his in first and dialled just the normal seven digits, like you do at home. ‘It’s dead,’ he said.

I thought I knew the score and, like a tit, said, ‘You forgot to dial 051 from outside Liverpool.’ Jimmy lashed his coin up the street. I’ve still got mine.

By two o’clock the sun had hit gas mark ten. I was down to my T-shirt, with me jumper tied round me waist. Wardy had done the same, and Jimmy was down to his skin. We bumped into a gang of Netherton Reds who were swigging from impressive, big, vase-looking wine bottles with basket handles. Wardy inspected one closer. ‘Fuckin’ ell, is there a genie in this?’ he said. They told us the bottles only cost two thousand lires each (about one pound fifty). Our sightseeing plans were about to be vinoed into touch.

We wandered the streets with our genie bottles. Every swig took our eyes up the walls of tall, baroque buildings that lined the roads and piazzas. The whole city was like a 3000-year-old museum. We passed an old tramp sprawled in a doorway with a flea-bitten dog tied to his wrist with string. Some Scouser had obviously walked past him earlier, because there was a piece of cardboard hanging off the tramp’s neck with the words ‘Gordon Lee’ written on it. We buzzed and threw a few thousand lires in his begging bowl. Whoever did it didn’t realise that it’d earn the tramp a tidy few bob off every Red who went past.

One bar we passed looked like something from The Godfather. Around three of its tables Reds were sprawled on chairs, all asleep in different positions like they’d been sprayed in a drive-by shooting. There was a huge cheer when a Manweb van drove past with Liverpool flags hanging out the windows. Someone said that the two lads in it were on sick leave and had sneaked the van out of the yard in Bootle.

By mid-afternoon the sun felt like it’d just been retubed. The official temp was 87°F, but in the suntrapped streets and piazzas it was easily around 100. In one street a Scouser dressed in a toga and wearing a blond Roman wig kept passing in a taxi … standing up in the sunroof waving to us like royalty. He went past about eight times shouting ‘Hail, Scousers’. We’d all shout it back, then bow.

The I-ties were all smiles and handshakes. In one hotel chefs and waiters waved down from windows. We waved our genie bottles back. Within seconds they were lowering bottles of wine and champagne down on long cords. Jimmy couldn’t stop blowing kisses up to them. Every I-tie who walked past was greeted with Red respect. The birds were stunners. There were a few bad attempts at chatting them up. The pick of the day was outside a packed bar, where Jimmy curtsied to a gorgeous brunette, held her hand and said, ‘D’yer take it up the Tex Ritter?’ I nearly choked. Boy was Rome the place to be that day.

By the time our genie bottles were empty, we were blowing bubbles. The train journey, the wine and the intense heat finally rugby tackled us. We crashed out in the shade of an ancient church and kipped on the pavement. In the hours that we slept, the siege of Rome continued. Every fountain and pool in the city had a pair of Scouse feet in it. One fountain we’d passed looked like Queens Drive baths. The elaborate Trevi was crawling with Reds. Though the bizzies weren’t keen on anyone bailing in, loads did. A few lads I knew from Gerard Gardens made the trip. One was Franny Carlyle, who was Scouse/I-tie so knew a bit about Rome. His mates didn’t have a clue. Shortly after they arrived, Franny said to them, ‘Listen, boys, we can’t leave Rome without goin’ the Colosseum.’ One of the lads genuinely and sincerely asked, ‘Is it a late bar?’

Thousands descended on that ancient old ruin, draping it with banners and playing footy outside. Others swarmed to gaffs like the Pantheon, St Peter’s Square and the Sistine Chapel – a place that me old buddies Stevie and Tony Riley described as ‘Nearly as beautiful as the Kop’. The day was a mixture of football fervour and cultural education. Everyday life for a lot of Reds was seeing graffiti-ridden walls and derelict flats on run-down estates, but here they were feasting their eyes on grandiose architecture, mosaic-covered courtyards and wall frescoes by fellas like Botticelli and Perugino. And let’s be honest, who could fail to be bowled over and gobsmacked by Michelangelo’s incredible ceiling! It definitely beat stipple or swirl Artex. For many this trip was where the first seeds of cultural awareness were planted. LFC weren’t just broadening our trophy cabinet; they were broadening our horizons and minds.

Wardy was grinning as usual when he woke us up at about five o’clock. I still owe him for that. Missing the FA Cup was a blessing, but if I’d have slept through the Rome game I’d have topped meself. Jimmy’s head was torched. He’d slid out of the shade and into the sun – his kite looked like it had been cheese-grated. We panicked and checked our pockets … it was all there. How the I-tie dippers didn’t have us off is a complete mystery.

We walked down a jigger into a proper back-street cafe. Wardy turned African again: ‘Food … spaghetti.’ When it came, it was full-on Italian. We stared at it, amazed at seeing white spaghetti.

‘What the fuck’s that?’ Jimmy said. ‘Ask them have they got any Heinz.’

It was our first hot meal in three days; we didn’t come up for air. I’ve been seriously hooked on bolognese ever since.

The match was kicking off at quarter past eight, which meant a taxi to the Olympic Stadium. On the way there the Colosseum flashed past the taxi window. By the time Jimmy said ‘Where?’ and turned round, it’d vanished. That was the sum total of our sightseeing, though we were in for a feast when we crossed the River Tiber near the ground. A tall, white stone obelisk graced the entrance to the Olympic Way. Behind it was a tree-lined stone avenue that led to the stadium. The sun was still laughing, making the avenue glow ultra-white with veins of red as thousands of Kopites streamed towards the Roman arena. When I got out the cab, I felt like kissing the deck. I was eighteen, I was raw and I was buzzing. This place looked like heaven on earth.

On the avenue red and white chequered flags were changing hands faster than an Olympic baton, at five thousand lires each (about three pound fifty). I reckon the I-tie who sold them must’ve retired on the banks of Lake Como from the business he did that night, though I wouldn’t begrudge him a single lire, because his flags were about to become a defining symbol of this whole amazing night, a visual jaw-dropper that’d soon be written into LFC history. A bit further on a couple more lads who I knew from town, Strodey and Ray Baccino, looked spaced out. At first I thought they were blitzed on vino, till Strodey managed to get his words out: ‘Davey, me prayers in the Vatican have been answered. We’ve just met Shankly.’ It was true. Shanks had walked up to the ground, mingling with all the Reds. ‘We’re gonna win this tonight, boys’ were the great man’s exact words. Strodey was totally gone. ‘Even the Roman statues were bowing as he walked past,’ he said.

Outside the stadium bizzies were frisking everyone for ale. It had been banned inside. I got past them and unravelled me battered match ticket. After three days’ worth of dossing, it looked like one of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The final stage of the pilgrimage was passing through those turnstiles. I closed me eyes for a sec, clenched me fists. I was in.

If there’s one sight I wanna see on me deathbed, it’s the scene that greeted me when I walked onto the Curva Nord terrace: a red and white panoramic rush of waving chequered flags, home-made banners, epaulettes, scarves, hats and streamers stretching three-quarters of the way around the ground. As far as breathtaking colour and beauty goes, it was right up there with the Swiss Alps – a vision that’ll never fade. Some of the raised banners I saw in our end are now legendary:

When in Rome, do as the Scousers do

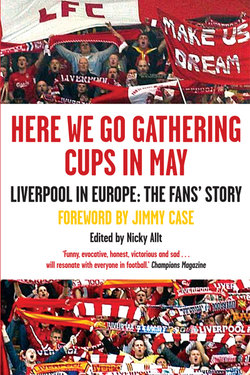

Here we go gathering cups in May

… and the mother, daddy and now grandad of them all, a twenty-four foot by eight-foot banner that became the story of Rome, the Scouse version of the Bayeux Tapestry that will be talked about and revered by Reds until the Liverbirds take flight: ‘Joey ate the frogs’ legs, made the Swiss roll, now he’s munching Gladbach’.

It was an honour to be in its presence. To Phil Downey, Jimmy and Phil Cummings, all’s I can say is well in boys – your banner will wave and echo in eternity.

Down at the front I was looking at the half-deserted Gladbach end when there was a tap on me shoulder. I turned around and, fuck me, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. It was Vinnie, standing there grinning like Wardy. His white clobber was absolutely rotten. First thing out of his mouth was, ‘I hope yer haven’t ate me sarnies.’ We laughed for ages. He’d managed to bunk a special via the platform nine fire-escape ladder. Lime Street was the only ticket checkpoint on the entire trip. I asked him about getting home. ‘Who cares?’ he said. Seeing him just added to the buzz. Everything was going right.

The racket from our end was non-stop and loud – not bad considering we were in an open-air stadium. Horns added to the din. You could see that the players were shell-shocked when they walked out and saw us all.

Tommy Smith: ‘I couldn’t believe it … and it did hit you.’

Emlyn Hughes: ‘Jesus Christ, we’re back in Liverpool.’

Terry McDermott: ‘Christ, how can we get beat for these lot?’

Terry Mac’s quote said it all. They couldn’t get beat, and the result we all know (you know the score). Every one of them dug deep and gave everything and more that night. They were just young lads, but under the genius of Bob Paisley they understood the historical importance and massive responsibility of it all. They represented who we were – our city, hopes, dreams and fantasies. They were how most of us got through a working week, our escape route from the dole queues, building sites, factories, mundane offices, domestic shit, wedge troubles or family grief. We needed them, and they needed us. We existed for each other, and together on one beautiful spring night we made history. If I had to choose a phrase to describe the moment, I’d put a footy slant on that famous old Churchill quote: ‘Never in the field of football memories has so much been owed by so many to so few.’

When the final whistle went, me, Jimmy and Wardy had a two-minute game of ring-a-ring o’ roses, which didn’t look out of place amongst the wreckage of the emotional bomb that hit the Curva Nord. It was a scene of total ecstasy, with quite a few tears thrown in. A lad near me was sobbing and being consoled. ‘He’s thinking of someone,’ his mate said. It’d be quite a few years till I’d understand where that lad went to that night, though he wasn’t in the zone for long. Minutes later he was buzzing alongside me on the front fence, watching the Reds parading on the running track. In between us a line of paranoid-looking bizzies ring-fenced our end. It was my first-ever glimpse of Big Ears. It looked massive, and it dazzled under the floodlights, shining brighter than Emlyn Hughes’s teeth. We all milked the glory till the boys disappeared down the tunnel through a posse of photographers and flashing cameras. Everyone was emotionally punch-drunk. The moment felt surreal, like something from a movie. But it was no illusion. We weren’t dreaming. Rome had just been conquered.