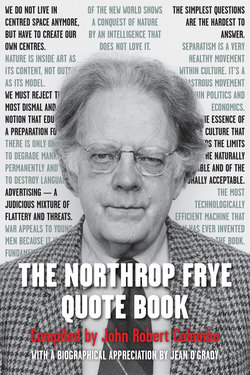

Читать книгу The Northrop Frye Quote Book - Northrop Frye - Страница 4

Biographical Appreciation

ОглавлениеJean O’Grady

Northrop Frye

What a guy

Read more books than

You or I

So begins a ditty about Frye popular at one time among undergraduates at Victoria College. It captures the local view of Frye — affectionate, proprietorial, somewhat in awe of the great man but by no means overwhelmed.

There is a curious dichotomy between this picture of Frye and that of the eminent man-of-letters celebrated by the world at large. Frye became an international phenomenon, the literary critic who opened up criticism as a discipline in its own right, and adumbrated a vast structure for the whole of literature. His books have been translated into twenty languages, including Serbo-Croatian, Korean, and Portuguese; his theories have been used to elucidate works from Old English to Russian. Scholars have held conferences on his work in Canada, the United States, Australia, Italy, China, Korea, and Inner Mongolia. The Northrop Frye papers in the Victoria University Library contain letters from twenty-six different colleges and universities offering Frye a job — and this is just in the eighteen years between 1959 and 1977. The offers range from a permanent appointment as Mackenzie King Professor at Harvard to a position in the English Department at Arizona State University.

In spite of this worldwide fame, and his thirty-eight honorary degrees, Frye spent most of his working life at the (with all due respect) comparatively obscure Victoria College in the University of Toronto. He enrolled there as an undergraduate in the college in 1929, studying philosophy and English; then, after his graduation, he studied theology at Emmanuel, the theological college of Victoria University, while doing some part-time lecturing in the college English department. As it became apparent that teaching was his vocation, the college authorities helped to send him to England for two years, to round out his English studies at Merton College, Oxford University. He persevered there, in spite of finding Oxford “dismally cold, wet, clammy, muggy, damp, and moist, like a morgue.” Upon finishing his studies at Oxford, he was relieved to be taken on permanently in the English Department at Victoria in 1939. There he remained, except for spells as a visiting professor, until his retirement. For years he rode the subway to work like any beginning lecturer, expounded his pass course in Biblical symbolism to undergraduates of every degree of sophistication, and often spent Saturday afternoons grading essays.

I first met him in this guise myself in 1960. I was going to study English Language and Literature and had been advised by my high-school guidance counsellor to enrol at Victoria so that I would, as they said, “get Frye.” I did get him, for several courses, and an amazing figure he was: dumpy and pasty-coloured, with an almost shifty air, as if he didn’t quite belong inside this mortal envelope. He would open his mouth and, in a quiet and unemphatic voice, give expression to the most searching analyses, the most suggestive generalizations, the most piercing insights, all in sentences and whole paragraphs perfectly controlled and modulated. Even his witty remarks were delivered deadpan, with just the occasional quick upturn at the side of his mouth if you seemed to get the joke.

Going back into the past, here’s a reminiscence of Frye as a lecturer by one of his students in 1946, political columnist Douglas Fisher, who had just arrived at college under the veterans’ preference with many other former soldiers:

Our class, perhaps forty [people], was stiff. The general tone was serious, almost apprehensive. It reeked of both earnestness and doubt.… At 9:05, a slight chap walked in, his suit too large, a dour Russian quality about its hang and texture. He was blond, his hair heavy, but haloed with wisps and snarls. (In his younger days, this blond mop had earned him the nickname “Buttercup.”) On first look, he seemed prissy, uncomfortable, yet curiously like a robot. Stiff — and we were stiffer.

He began while staring out the window.… “My subject today is George Bernard Shaw.…” and he was away. A tape recorder would have picked up little but the teacher’s voice. Except for an occasional titter, the class didn’t loosen up. When the bell rang, the man stopped talking, bobbed his head, and left.

He was no sooner gone from the room when an uproar of comments made the place noisy.

“This can’t be university, it’s too entertaining.”

“What’s this man’s name?”

A girl beside me looked at me for seconds but her mind wasn’t there. When her beatific smile finally broke, she said, “That was better than any movie I’ve ever seen.”

What I knew was — if this was university, I wanted a lot more of it, and the teacher.… What a break! Northrop Frye as first voice heard at university.

Frye was always the opposite of grandstanding or charismatic, the conduit of a force that came purely from the mind and owed nothing to physical stature. In 1950, when he spent a year as a visiting professor at Harvard, he went to a store where the proprietors took a friendly interest in the students. As Frye relates it, “The clerk asked me what I was studying, and I said, with only a touch of shrillness, that I was teaching. Just for the summer, of course. He wrapped my parcel, handed it to me, and said, ‘I hope your permanent appointment comes through all right.’”

Working on The Collected Writings of Northrop Frye, I encountered another form of this contrast between appearance and reality. The edition includes not only the published works, but also letters written to his future wife Helen, diaries, and seventy-six densely packed notebooks, in which Frye wrestled with trains of thought, worked and re-worked the shapes of his books, and reflected on his own strengths and weaknesses. At the end of his life, instead of burning these notebooks, he allowed them to pass to the Northrop Frye Fonds at Victoria’s E.J. Pratt Library, and thus implicitly gave us our liberty to publish them. It is not too much to say that they reveal an entirely new Frye, unsuspected by the general public and even by most of his associates: one given to waspish comments on his colleagues, or to politically incorrect remarks like “Probably one has to lie to men — certainly to women.”

The letters written during his courtship of his wife have aroused much interest, a typical reaction being, “Who would have believed that Northrop Frye could be so amorous?” And who would believe, before the notebooks were published, that Frye longed to write a novel — indeed, to write eight novels, each in a different mode, covering between them all types of fiction from the comedy of manners to the war novel.

He is sometimes accused of being exclusively concerned with Western literature, yet these notebooks and diaries reveal that he was reading about Eastern philosophy in the 1940s, long before it became fashionable, and that he hoped to write what he called a “Bardo” novel based on inter-life existence as described in the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

His published works seem complicated enough, but it now appears that they were just the tip of the iceberg. His ambition was to write a series of eight books that he called the “ogdoad,” which would survey the whole of human speculation, providing a guide to the symbolic universe, or what he once described as “the architecture of the spiritual world.” Hayden White spoke more truly than he knew when he remarked that he sensed a subterranean Frye — that when talking to Frye he “had the feeling that he was always in that shop in the back of the mind of which Montaigne spoke, working on some intellectual issue.”

In suggesting this series of contrasts, between inner man and public persona, awkward figure and eloquent speaker, Toronto teacher and international icon, I’m working with categories that are not exactly parallel. But I feel I have a warrant in the practice of Frye himself, that inveterate manipulator of equivalents, correspondences, and categories. The particular binary oppositions I’ve been suggesting seem to me important because they lead in to something very central to Frye’s thought, which might best be described as the relation between the individual and his society. In Frye’s case, the question involves his own Canadianness and his Protestant inheritance. How is the individual absolutely himself yet the committed member of a corporate entity? The question is parallel to one encountered in his literary criticism, where Frye maintained that he recognized the uniqueness of the work of art, while his critics complained that he was obliterating it by relating the work to generic and archetypal patterns.

As background to these matters, I’d like to look briefly at the outlines of Frye’s thought as a whole. Though Frye first gained recognition with his book on Blake, Fearful Symmetry, in 1947, it was Anatomy of Criticism, published in 1957, that brought him worldwide attention. Written with verve and wit, this Canadian classic not only ushered in that explosion of serious critical thought that made “theory” the dominant genre in the last half of the twentieth century, but it also constituted a readable, civilized contribution to literary discourse in the tradition of Johnson, Arnold, and Eliot.

When it was written in the 1950s, literary criticism was a mixture of appreciation, explication of themes, study of sources and influences, biographies of authors, historical background, and the “New Criticism” that studied lyrical poems line-by-line. The Anatomy’s revolutionary proposal was that criticism was a science, of which all these practices were constituent parts, and it was so in virtue of the fact that literature itself forms its own universe with its own laws. Authors shape their works according to these laws or conventions, however much they may seem to be capturing life or expressing their emotions. Poems are made from other poems; or, in the words of Yeats,

There is no singing school but studying

Monuments of its own magnificence.

Thus, instead of a collection of individual works, organized mainly chronologically, you had a body of work that could be anatomized just as a human body could; and this is what Frye proceeded to do.

Criticism may look at literature from several different perspectives, expounded in the four main chapters of the book. In “First Essay: Historical Criticism,” Frye sees the history of literature as the increasing displacement of a mythic core toward realism. As we move through the various modes — mythic in earliest time, romantic in the Middle Ages, high mimetic in the Renaissance, low mimetic in the nineteenth century, and ironic today — so the status and power of the hero decline from the god or godlike man of myth, through the ordinary man, to the victim or powerless man in irony. (Frye said that he used the term “man” for “man or woman” on Sydney Smith’s principle that “man generally embraces woman.”) Non-narrative or thematic literature, such as most poetry, goes through a parallel sequence of five modes based on the relation between poet and audience.

The “Second Essay” approaches literature not as developing through time but as an organism spread out simultaneously in space. Here Frye introduces his notion of “polysemous meaning,” that a text can be looked at on different levels; he suggests five such types of criticism, based largely on the approaches their practitioners take to symbolism — the literal, the descriptive, the formal, and then the archetypal and the anagogic, which are his particular province. On the archetypal level, we relate the poem to literature as a whole, studying genres, conventions, and images that are repeated from poem to poem. Seen as a whole, in its archetypal phase, literature visualizes the goal of human work, or of Paradise regained. The final phase, the anagogic, is difficult to grasp: in it, universal archetypal symbols such as the city, garden, quest, and marriage define a literature that has “swallowed” nature: the distinction between man as perceiving subject and nature as object has disappeared, and “nature is now inside the mind of an infinite man who constructs his cities out of the milky way.” Sometimes I think of this as the ecologist’s nightmare.

The details of archetypal criticism, studied in the “Third Essay,” are organized into two areas, the static and the dynamic. Statically, Frye discerns two groups of archetypal symbols, corresponding to the two extremes of wish and nightmare: the apocalyptic imagery of gardens, sheepfolds, bread and wine, and so on, which are the metaphors of human desire, and the demonic imagery of monsters, waste lands, and fiery furnaces, which define all that man rejects. For the dynamic movement of plot, Frye invokes one of the most basic patterns, the cycle, as in the changing of the year from spring, to summer, to fall, to winter, and back to spring. He distinguishes four basic, pre-generic plot types — comedy, romance, tragedy, and irony, which he positions on this circle.

Finally, the “Fourth Essay” discusses rhetorical criticism, in which literature is looked at according to the genres such as epic, lyric, and satire.

This approach to literature was so novel and so suggestive that within a few years Frye had become the darling of North American graduate-school English departments; carrying a copy of his book was the very hallmark of the serious and up-to-date student. He was the first individual critic to have a conference of the English Institute dedicated to his work, in 1965, at which time Murray Krieger made his oft-quoted remark that “he has had an influence — indeed an absolute hold — on a generation of developing critics greater and more exclusive than that of any one theorist in recent critical history.” Of course, this influence was subject to historical fluctuation: during the heyday of Deconstruction some years later, any attempt to see a grand structure was suspect, and Frye became for a while a past number.

But even at the time of its publication, there was considerable resistance to The Anatomy of Criticism. Some critics, appalled at the Anatomy’s encyclopaedic subdivisions, balked at the thought that swallowing such an enormous pill was necessary for its salutary effects. Frye always denied the accusation that he was trying to make everyone accept his whole “system,” or that his project was like a straitjacket; he remarked to an interviewer that perhaps he would ultimately be found less useful as a systematizer than as a quarry for later thinkers, “a kind of lumber-room … a resource person for anyone to explore and get ideas from.” He also declared his own indifference to his future reputation: “If posterity doesn’t like me, the hell with posterity — I won’t be living in it anyway.”

Perhaps the major contemporary criticism of the Anatomy was that the book minimized the writer’s immediate involvement in and meaning for his society. To Frye’s annoyance, the literary establishment associated him particularly with two specific ideas, that criticism should be a science, and that the role of the critic was not to evaluate individual works. For some objectors, this turned literature into an autonomous verbal structure to be studied in and for itself, cut off from social history, from its authors’ concerns, and from the realistic representation of the world. The Fryegian critic seemed a dry anatomist, utterly uninvolved in the needs of his readers for guidance and wisdom, and of his society for literary discourse.

Even on a personal and biographical level, the notion that Frye as a critic was removed from society and its concerns was radically unjust, as he was always deeply involved in Canadian culture. He may have worked out his critical principles from his study of William Blake, but he honed them on Canadian poetry: for ten years, from 1951 to 1960, he wrote the “Poetry in English” section of the University of Toronto Quarterly’s annual survey of Canadian literature, for which he had to read virtually all the poetry published during the preceding twelve months. This, in the days before the full flowering of Canadian literature, must have been tedious at times, but wit and wordplay abound in Frye’s reviews, whatever may be said of the poems themselves.

Although, as a “reviewing” rather than a strictly “academic” critic, he had to relax his stand against value judgments and offer some guidance about what was worthwhile reading, he never attempted to tell the poets how to write. Margaret Atwood described Frye’s usefulness to the writer in terms of his recognition of genre: “We all know the doggerel poem about critics: ‘Seeing an elephant, he exclaimed with a laugh, / What a wondrous thing is this giraffe.’ Perhaps one of his greatest gifts to writers was his lifelong work to ensure that if you created an elephant, it would never again be mistaken for a giraffe.” In these reviews, he concentrated on encouraging conversation about Canadian poetry and in developing an informed reading public that would allow that poetry to flourish — which it did in part thanks to his efforts.

On a theoretical level, Frye turned to probing the backbone of the Anatomy, the existence of a literary universe that provides an imaginative vision for society. While continuing to produce a stream of practical criticism — books on Shakespeare, Milton, and T.S. Eliot, articles on the Renaissance, Yeats, Joyce, Samuel Butler, and numerous others — he also wrote works of general theory such as The Well-Tempered Critic (1963) and The Critical Path (1971) that explore the relation between critic, poet, and society. In The Critical Path, subtitled “An Essay on the Social Context of Literary Criticism,” he put forth some important new conceptions of social development. According to his analysis, there is a constant dialectic in human history between the myth of concern and the myth of freedom. The myth of concern is society’s central mythology, the body of what it believes as a society and what holds it together. (Later Frye split this into the primary concerns essential for survival, and the secondary concerns of religion, politics, and ideology.)

Authors, Frye says, tend to be children of concern, in that they address mankind’s enduring hopes and fears through their images of wish and nightmare, and their depiction of the business of loving, gaining a living, and facing death. Against this concern stands the myth of freedom, a sort of liberal opposition which criticizes the myth of concern from an individualistic, often scientific, point of view. Included in the myth of freedom are all the academic disciplines, which must be conducted as scientifically as their subject matter allows, and must not have any ideological bias or outside loyalties. Literary criticism is one of these disciplines, indeed a central one: its subject matter may be concerned, but it must itself remain in the myth of freedom.

In the background of this defence of the critic or teacher’s freedom from ideological and social constraints — indeed, part of the reason for undertaking it — was the student revolution of the late 1960s and 1970s, with its demand for immediate “relevance” and moral engagement in university studies, along with individual choice of a congenial curriculum. Frye was actually spending a term as visiting lecturer at Berkeley when the first violent student unrest broke out in the spring of 1969, leading him to say that the student radicals reminded him of a sentence in an old cookbook: “Brains are very perishable, and unless frozen or pre-cooked, should be used as soon as possible.” His response was consistently to defend the values of a traditional, disinterested liberal education. “An arts degree is useless,” he would say, “if it isn’t, it isn’t worth a damn.”

Frye saw that the student came to university stuffed with the clichés and received ideas of society, which were essentially unreal and phantasmagoric. Fads come and go, endless consumer goods are consumed or thrown away, politicians are assassinated, millions mourn a Diana they never knew. For four years, the student could withdraw himself from this society, and concentrate on the more stable forms proffered by mankind’s achievements in the arts and sciences: on the authority of the logical argument, the repeatable experiment, the compelling imagination. In the light of this vision provided by culture, the student will become a radical critic of what is — not a “well-rounded individual,” with its comfortable overtones of contentment and softness, but maladjusted and crotchety, “a critical and carping intellectual,” “probably one of that miserable band who read the Canadian Forum.”

But sometimes Frye wondered if it was too late, worrying that by the time a student reached university it would be impossible to influence his mind, since it was already pre-programmed by television and advertisements. He became involved in schemes for earlier education, helping to found a curriculum institute in which university professors joined with elementary and high-school teachers to suggest improvements in the school curriculum, and later overseeing the production of a series of English readers for grades seven to thirteen. His concern was to keep the imagination in play, for only through imagination could the individual think metaphorically and engage in the play of mind through language that constructed reality in human form.

The most striking of the shorter essays that continue to discuss this theme, “The Responsibilities of the Critic,” given as a speech at Johns Hopkins University in 1976, marks a vital transition in Frye’s approach and is almost a manifesto for the second half of his career. In this talk, he is less concerned with the articulation of the literary universe as a whole than with the transformative potential of individual works. Concentrating on the reader and the act of reading, Frye contends that literary works may become a focus of consciousness and open up new worlds of perception. “It seems strange,” he says in the essay “Expanding Eyes” (1975), “to overlook the possibility that arts, including literature, might just conceivably be what they have always been taken to be, possible techniques of meditation … ways of cultivating, focusing, and ordering one’s mental processes.” He talks of Blake’s offering his works in this spirit, not as icons but as mandalas, things for the reader to contemplate to the point at which he or she might reflect, “yes, we too could see things that way.” The critic has a role in unlocking the power of such prophetic writers, helping to turn literature from an object to be admired to a power to be possessed. He does so not by judgment but by an act of recognition: “What the critic tries to do is to lead us from what poets and prophets meant, or thought they meant, to the inner structure of what they said,” thereby opening a window into the created world.

Increasingly, Frye turned to the powers of language in all its aspects, literary and non-literary, to convey vision; latterly, he tended to define himself as a “cultural critic” rather than a “literary critic.” In Words with Power, Frye studies this kerygmatic or prophetic authority in both the Bible and literature. He invokes Longinus’s treatise On the Sublime in describing those dazzling moments in our response to art when the ego is dispossessed and “all the doors of perception in the psyche, the doors of dream and fantasy as well as of waking consciousness, are thrown open.”

The Great Code in 1981, and Words with Power in 1990, both begin with expositions of the theory of language that respond to the growth of linguistics and semiotics in the previous decades. Language is seen to go through three phases, later expanded to four — the metaphorical, the dialectical, the rhetorical, and the descriptive — each in turn being dominant. Literature, however, keeps alive the earliest, metaphoric phase of language; and in these last major works, Frye delves into the basic source for those metaphors in the Bible. The Bible itself is written in the language of myth and metaphor, and thus it is a mistake to read it “literally” (as that phrase is commonly understood): its literal meaning is metaphorical. But the Bible’s myths and metaphors are not hypothetical, like those of literature, since they are offered as myths to live by and metaphors to live in: they attempt to influence the reader in his way of life. Unwilling to call biblical language merely rhetorical, Frye suggests a fifth type of language, the kerygmatic, which is a rhetoric of proclamation on the “other side” of myth and metaphor.

In Words with Power, Frye studies this kerygmatic or prophetic authority in both the Bible and literature. The Great Code, whose title comes from Blake’s assertion that “The Old and New Testaments are the Great Code of Art,” lays the groundwork with a study of the Bible itself. As in the “Third Essay” of Anatomy, there are two aspects, the cyclical and the dialectical. Looked at as a plot, or mythos, the Bible is a comedy: it gives the history of mankind, under the name of Israel, from Creation in Paradise, through a fall into time and encroaching darkness, to Apocalypse and the regaining of Paradise, with a series of falls and recoveries in between.

Seen dialectically, the Bible’s imagery falls into the two categories, mentioned before, of apocalyptic and demonic imagery. Its images of desire — shepherd, lamb, bridegroom, tree of life and so on — are ultimately all identified with a single figure, which is Christ. This human figure is both the fulfilled individual and the giant form of his society. In Paul’s words, “So we, being many, are one body in Christ”; in Frye’s interpretation, “the community with which the individual is identical is no longer a whole of which he is a part, but another aspect of himself.”

Frye’s Return of Eden, a study of Milton, ends with “the realization that there is only one man, one mind, and one world, and that all walls of partition have been broken down forever.” Frye is not inculcating religious doctrine here, since, from a literary point of view, “belief” in Christ is not in question. Rather, he is pointing out that mankind’s imagination culminates in a single human figure, who is both one and many, the individual glorified as his social body.

Those familiar with Blake will recognize that Frye has come full circle back to Fearful Symmetry. Blake’s universe is populated by mighty individual figures, such as the human imagination, embodied as the chained Los; or a vengeful God, represented as Noboddady. For Blake, it is the local that becomes the universal, not some construct abstracted from many locals and resembling none. He believed in the radiance of the particular: a world in a grain of sand, eternity in an hour. In so stating, I too hope to have come full circle, by a long route recalling my earlier question of the relation of the individual to his society. Society — that is, a real society — is the fulfillment of the individual, not an obliteration of him.

What of Frye himself and his relation to his society? The particular milieu he was born into was middle-class, white, Canadian, and Methodist. Methodists are supposed to undergo a “conversion,” the defining experience of their lives, when they are convinced of their utter sinfulness and of God’s ability to forgive them. It’s typical of Frye that he underwent an anti-conversion: he had been brought up by a church-going mother, but one morning, at the age of about fifteen, walking to school, he discovered, as he put it, that “the whole shitty, smelly garment of fundamentalism dropped off into the sewer and stayed there,” and he realized that he had never really believed in the vengeful God who threw some into hell and rewarded others with a permanent appointment in the heavenly choir. Nevertheless, he remained within the Protestant tradition, imbued with its Bible culture, its radical individualism, its emphasis on the spirit. However, he sought all his life to define a religion that did justice to man’s spirituality without falling into what he saw as superstitious idolatry.

The religion he defined was radical to say the least. By the time of his last book, The Double Vision (1991), he had virtually jettisoned the ideas of God the father, of the historical Jesus as an atoning figure, of the afterlife, of the Creation as a historical event, and of the Apocalypse as something that was likely to happen. As we might guess, they’re all metaphors. What remains is the figure of Jesus, who is the creative principle linking mankind with the divine, and through whose vision man sees the eternal here and now.

Often enough, in his early years, Frye felt a deficiency of the eternal at Victoria College, with its endless fuss over locking the girls into residence by 11:00 p.m. and its insistence on never serving a glass of wine; but, particularly as the multiversity developed, he stressed the vital importance of colleges with specific traditions. He felt a loyalty to his community and enjoyed being part of it, even to serving as its principal for nine years.

As for his Canadian identity, that was also something he cherished. He could no more be an American than he could be a Catholic, and he was true to his roots in not forsaking Canada for the more lucrative field of the United States. According to his reading, Canadians differed from the Americans both geographically and historically. In its history, Canada had skipped over, intellectually speaking, the rational eighteenth century, and was always the home of a more Tory, less revolutionary attitude than the American. Hence, “Americans like to make money: Canadians like to audit it.” Geographically, Canada lacked an eastern seaboard where settlement was concentrated, and the immense distances stretching out between isolated towns led to a garrison mentality in regard to nature. Such speculations on the nature of Canadianness feature largely in his celebrated “Conclusions” to the two editions of Literary History of Canada, which have become an honoured part of the literature they discuss.

Frye once defined the Canadian genius as the ability to produce strange hybrids, such as the University of Toronto in education, the United Church in religion, and Confederation in politics. He himself has some of this Canadian characteristic of contrasting entities strangely combined: the local teacher and the world celebrity; the committed Christian and the man who didn’t know whether Christ ever existed and didn’t think it much mattered; the believer in community and the shy introvert; the eloquent speaker and the tongue-tied conversationalist. On this showing, he himself was one of our most characteristic as well as our most honoured and widely quoted products.