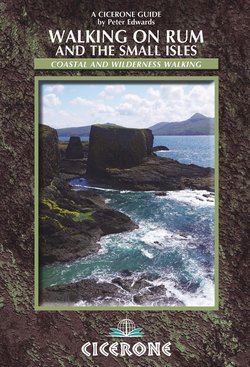

Читать книгу Walking on Rum and the Small Isles - Peter Edwards - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеRUM

Rùm

Heading east to Glen Shellesder with Bloodstone Hill towering above Glen Guirdil to the west (Walk 3, Day 3)

Introduction

On the Dibidil pony path, with Sgurr nan Gillean dominating the horizon (Walk 3, Day 1)

Rum is by far the largest of the Small Isles, and at some 100 square kilometres and 14km (8½ miles) north to south by 13.5km (8½ miles) east to west is the 15th largest of the Scottish islands. It is the wettest and arguably the most mountainous island of its size in Britain. Its striking profile of jagged basalt and gabbro mountain peaks testifies to its volcanic origins. Rum’s highest peaks, Askival (812m) and Ainshval (781m), are Corbetts – those Scottish mountains between 2500 and 3000 feet (762m and 914m) with a relative height of at least 500ft (152m): Rum is the smallest Scottish island to have a summit over 762m (2500ft).

Kinloch, the island’s only settlement, is at the head of Loch Scresort, the main anchorage, some 27km west of Mallaig and the Morar peninsula on the mainland. Rum is 11km (7 miles) south of Skye at its nearest point and 23km (14 miles) north-west of the Ardnamurchan peninsula. Rum has a tiny population – around 30 – and when the village of Kinloch is left behind a true sense of remoteness is soon found amid the island’s wild, dramatic and sometimes challenging landscape. The only other habitations, besides the bothies at Dibidil and Guirdil, are the red deer research base at Kilmory Bay and the Scottish National Heritage (SNH) lodge at Harris.

Rum ponies at Harris (Walk 3, Day 2 and Walk 7)

The distinctive volcanic chain of hills comprising the Rum Cuillin is the obvious and immediate draw for outdoor enthusiasts, whether for hill walking, scrambling or rock climbing. A round of the Rum Cuillin makes for a challenging day in the hills and usually features somewhere on the ‘to-do’ list of Scottish mountain aficianados.

But for the adventurous walker there is much more to Rum than the Cuillin. This guidebook includes detailed route descriptions for five major walks – including a three-day walk around the coast and circular routes around the remote western hills – and several shorter routes.

Land Rover tracks cross the island from Kinloch to Kilmory and Harris, and there are several long-established footpaths, including the well worn track up the Allt Slugan to the Coire Dubh – gateway to the Rum Cuillin – and the pony path around the coast from Kinloch to Dibidil bothy and Papadil. Other areas lack distinct paths, necessitating detailed route descriptions and mapping – all the more so as Rum is exceptionally prone to cloud cover, with associated implications for navigation. Walking conditions on Rum are often wet and rough: it is essential that walkers are properly prepared and equipped.

Staying on Rum

Rum’s community is undergoing a period of change with the phased transfer of assets from Scottish Natural Heritage to the Isle of Rum Community Trust. The Trust now owns around 35 hectares of land and 11 residential properties in and around Kinloch, and is tasked with managing community land and assets for the community and the visiting public, alongside promoting sustainable rural regeneration.

As a result the accommodation situation is in a period of flux, and it is worth checking the Isle of Rum website well in advance of a visit to see what is available: www.isleofrum.com. Accommodation provision at the time of writing can be found in Appendix B.

Geology

Looking from Askival to Trollaval (right) and Ainshval (left), with Ruinsival beyond (Walk 1) (photo: Peter Khambatta)

The Rum Cuillin forms the impressive skyline of jagged peaks dominating the south of the island. The northern peaks of the range are principally formed of peridotite basalt and gabbro, similar in construction to the Black Cuillin of Skye. The southern peaks are Torridonian sandstone capped with quartz-felsite and Lewisian gneiss, and the rounded granite hills of Ard Nev, Orval, Sròn an t-Saighdeir, Fionchra and the lava-capped summit of Bloodstone Hill are in the island’s west.

Rum is the core of a volcano that developed on a pre-existing structure of Torridonian sandstone and shales resting on Lewisian Gneiss. Volcanic activity 65 million years ago formed a dome over a kilometre high and several kilometres across. Pressure from below caused fractures to form around the dome, which collapsed, forming a caldera. The caldera floor was gradually covered by rocks and debris, consisting largely of Torridonian sandstone and Lewisian gneiss, which was compressed, forming rocks known as breccias, found in Coire Dubh. The vestiges of the dome are evident on the slopes of the Rum Cuillin, where the Torridonian rocks incline steeply away from the adjacent igneous rocks.

Weathered Torridonian sandstone formation near Kilmory Bay, north-east Rum (Walk 3, Day 3 and Walk 7)

Magma, ash and rock erupted into the caldera, along with gas clouds known as pyroclastic flows which formed rocks known as rhyodacites, found around the margins of the Rum Cuillin and on the ridge between the summits of Ainshval and Sgùrr nan Gillean.

The western hills, including Orval and Ard Nev, are predominantly composed of coarse-grained granites formed from magma that crystallised below the Earth’s surface. The Rum Cuillin is mostly composed of layers of pale, hard gabbro interspersed with brown, crumbly peridotite, rocks created from cooling magma at the base of the magma chamber, especially on Hallival and Askival. There are some outcrops of the pre-volcanic Lewisian gneiss near Dibidil in the south-east corner of the island, and extensive Torridonian sandstone is found in the north and east.

Basalt dikes are found on the north-west coast between Kilmory and Guirdil: erosion of the less-resistant rock into which they are intruded has left them exposed as natural walls. They tend to radiate out from a point in Glen Harris, which suggests that this was the centre of volcanic activity. Bloodstone Hill was formed by lava flowing away from this volcanic centre; gas bubbles in the rock filled with heated silica, which cooled to form green agate flecked with red, hence the name ‘bloodstone'.

The last major glaciation of the Quartenary Ice Age began about 30,000 years ago, when glaciers covered the island and the tops of the highest mountains protruded through the ice as ‘nunataks'. Frost-shattering created scree slopes on these summits, and freeze-thaw processes have sorted rock particles into remarkable regular patterns such as the stone stripes and polygons near the summit of Orval.

The ice sheets retreated around 10,000BC. During glacial periods sea levels dropped, rising again when the glaciers melted. The landmass sank under the weight of the ice cap, then rose again as the ice retreated. The land continued to rise beyond the maximum increase in sea level, forming the raised beaches found around the coastline 12–30m above the present sea level, especially between Harris and A'Bhrideanach.

Tundra vegetation gave way to forest. The climate warmed 6000 years ago, encouraging forestation to a higher altitude than at present, before becoming cooler and damper around 1000BC, and peat expanded at the expense of woodland. A dearth of cultivable land also led to woodland clearance by early farming communities.

History

Kinloch Castle

Mankind probably first reached parts of Scotland during the mild phases of the last glacial periods of the Quartenary Ice Age, but retreated as the climate deteriorated. All traces of Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) settlement were obliterated by the ice sheets during the subsequent glaciation. Archaeological evidence established the existence of Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) settlement in some areas of Scotland from around 6500BC, with hunter-gatherers in seasonal occupation as early as 10,500BC on the fringes of the retreating ice sheet.

Traces of the earliest known human settlement in Scotland were found on Rum at a site near Kinloch. Concentrations of bloodstone microliths indicated the manufacture of stone tools and roasted hazlenut shells were radiocarbon dated to 6500BC. A shell midden at Papadil, cave middens at Bagh na h-Uamha and Shellesder and tidal fish traps at Kinloch and Kilmory are also characteristic of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers.

The Stone Age to St Columba

Peat core samples from Kinloch revealed soil erosion and a decline in tree pollen, suggesting that woodland clearance for cultivation occured during the Neolithic (New Stone Age), from around 2700BC. Bronze Age traces on Rum are limited to hut circle sites and finds of barbed and tanged bloodstone arrow heads. Like many marginal Bronze Age settlements, Rum may have been abandoned during a period of harsh climatic conditions prevailing in northern Europe after the eruption of the Icelandic volcano, Hekla, about 1150.

Iron-working skills and characteristic structures including brochs, duns, wheelhouses, crannogs and souterrains were introduced to Scotland around the middle of the first millenium BC by Celtic people migrating from continental Europe. Rum possesses only a few crude promontory fort sites at Kilmory, Papadil and Shellesder. Decorated pottery sherds are the only other Iron Age artefacts retrieved on the island.

The first written references to the early Caledonian people come from the Romans, following Agricola’s expedition north in AD81. References to the ‘Picti’ first appeared in Roman accounts around AD300, though it is probable that the Picts were an assortment of racial and cultural groups – including the aboriginal Bronze Age peoples – bound together by the threat of the Romans. It is likely that the population of Rum at this time was Pictish in origin.

Early in the third century an Irish tribe – Scotti of Dál Riata – began the colonisation of Kintyre and the Inner Hebrides. The process of conquering and colonisation continued until late in the fifth century when the kingdom of Dalriada established its capital at Dunadd, following the decisive invasion of Argyll. St Columba came from Ireland to Iona around 563 and established a monastery that became an important centre of learning and spirituality. Columba’s followers, the early Celtic Christian missionaries, set about converting the populations of the islands and the mainland. One of their number, Beccan the Solitary, became a monk at Iona in 623 and then a hermit – probably on Rum.

The Viking era

In 794 Iona suffered the first of many Viking raids, which gradually forced the monastery into decline. In common with many Hebridean islands, Rum came within the Norse sphere of influence. The Norsemen ruled the Small Isles from 833 until the Treaty of Perth in 1266, when the Isle of Man and all the Hebrides were ceded to Scotland. The only tangible evidence of a Norse presence on Rum to date is a piece of carved narwhal ivory unearthed at Bagh na h-Uamh in 1940.

The Norse legacy is most obvious in the toponymy of the island, whose name may itself derive from the Old Norse rõm-øy, meaning ‘wide island', or the Gaelic ì-dhruim, meaning ‘isle of the ridge'. The name ‘cuillin’ also comes from the Norse kiolen, meaning ‘high rocks'. Several of the principal peaks have Norse names, with ‘-val’ deriving from fjall, meaning ‘hill': Askival (812m) and Ainshval (781m) ('spear-shaped hill’ and ‘rocky ridge hill’ respectively), Hallival (722m), Trollaval ('mountain of the trolls', 700m), Barkeval ('precipice hill', 591m), Ruinsival ('stone-heap hill', 528m): Gaelic names are Sgùrr nan Goibhrean ('goat hill', 759m) and Sgùrr nan Gillean ('peak of the young men', 764m). The place-names Dibidil and Papadil are Norse.

The Middle Ages to the Macleans

During the 13th century the island was in the possession of the powerful Macruari clan for a brief period until 1346, when Rum was chartered to Clanranald – known as the Lords of the Isles – who ruled much of the Hebrides from Finlaggan on Islay for 150 years. The Lordship came to an end after John MacDonald II’s duplicitous treaty with Edward IV of England against the Scottish Crown, which led to the forfeiture of all MacDonald land.

From the early Medieval period Rum was noted for its deer and ‘excellent sport’ and was probably used as a hunting reserve by the nobility. By the mid-16th century Rum was in the possession of the MacLeans of Coll, then in 1588 the Small Isles were assaulted when Lachlan Maclean of Duart led a raiding party including 100 Spanish marines from a galleon of the defeated Armada anchored at Tobermory. The islands’ settlements were torched and their inhabitants murdered. In 1593 King James VI received a report indicating that Clanranald had re-occupied the island, but despite these temporary setbacks the Macleans of Coll kept possession of Rum for more than three centuries.

By the late 17th century Rum’s status as a hunting reserve had declined and the human population had increased. The inhabitants caught fish, grew barley and potatoes and raised Black cattle for export to the mainland. Conditions were primitive and the dearth of viable farming land stretched resources. The needs of a growing population led to the extermination of the native red deer during the latter half of the 18th century.

At the beginning of the 19th century there were nine hamlets on Rum and the local economy enjoyed a boost from the kelp industry. However, in 1825 the island was leased to Dr Lachlan Maclean, a relative of Hugh Maclean of Coll. Like many Highland landlords, Maclean, in search of profit, decided to clear the land and turn it over to 8000 blackface sheep. Rum’s population was given a year’s notice to quit its homes. On 11 July 1826 around 300 inhabitants boarded the Highland Lad and the Dove of Harmony, bound for Cape Breton in Nova Scotia. The remaining 130 followed in 1828 on the St. Lawrence, along with some 150 inhabitants of Muck, another of Maclean of Coll’s properties. Then mutton and wool prices declined and the enterprise failed; Lachlan Maclean left Rum, bankrupt, in 1839.

Into the 20th century

In 1845 MacLean of Coll sold Rum to the Marquess of Salisbury, who reintroduced red deer and converted the island into a sporting estate, and for over a century Rum was known as the ‘Forbidden Island', as uninvited visitors were actively discouraged.

After the Marquess of Salisbury’s death, the island was bought by Farquhar Campbell in 1870, who passed it on to his nephew. In 1888 Rum was acquired by John Bullough, a cotton machinery manufacturer and self-made millionaire from Accrington in Lancashire who had previously leased the island’s shooting rights. The prospectus for the 1888 sale described Rum as: ‘The most picturesque of the islands which lie off the west coast of Scotland, it is altogether a property of exceptional attractions...as a sporting estate it has at present few equals'. At this time the population numbered between 60 and 70 shepherds, estate workers and their families. When Bullough died in 1891, ownership of the island was assumed by his son, George Bullough.

Sir George Bullough – he was knighted in 1901 – changed the traditional spelling of the island’s name to Rhum in 1905, allegedly to avoid the connotations in the title Laird of Rum (the spelling reverted to Rum in 1992 when SNH took over from the NCC). However, Sir George’s most striking legacy is the incongruous and often maligned Kinloch Castle, built during the last years of the 19th century and completed in 1902. The castle was built from red sandstone quarried at Annan in Dumfriesshire. A hundred stonemasons and craftsmen were brought from Lancashire, and Sir George purportedly paid the workforce extra to wear kilts of Rum plaid.

Sir George Bullough’s collection of exotic Edwardiana adorns the interior of Kinloch castle

The estate employed around a hundred people, including 14 under-gardeners to maintain the extensive grounds, which included a nine-hole golf course, a bowling green, tennis and racquets courts, heated ornamental turtle and alligator ponds and an aviary housing birds of paradise and humming birds. Soil for the grounds was imported from Ayrshire, and grapes, peaches, nectarines and figs were grown in the estate’s glasshouses. The interior boasted an orchestrion – a mechanical contrivance that could simulate the sounds of brass, drum and woodwind – an air-conditioned billiards room and an ingenious and elaborate central heating system, which fed piping hot water to the Heath Robinson-esque bathrooms, replete with ‘jacuzzi', while also heating the glasshouses and ornamental ponds.

Sir George and Lady Monica Bullough usually resided at Kinloch Castle during the stalking season and would entertain their wealthy and important guests in some style. Deer stalking was one of the primary diversions for the Bulloughs and their guests and a day’s stalking on the hill would be followed by a sumptuous evening meal served at the dining suite, which had originally graced the state rooms of Sir George’s yacht Rhouma. After dinner the company would repair to the magnificent ballroom, with its highly polished sprung floors and cut glass chandelier, to dance the night away.

Harris Bay and the Bullough mausoleum (Walk 3, Day 2 and Walk 7)

This exalted era drew to a close with the coming of the Great War. Most of the estate’s male staff went to Flanders and many never came back. The estate fell into disrepair during the war and as Britain’s fortunes declined in the post-war years, the Bullough finances also gradually dwindled, along with their interest in Rum. Sir George died in France in July 1939 and was interred in the family Mausoleum at Harris Bay. His widow continued to visit Rum as late as 1954. She died in 1967, aged 98, and was buried next to her husband in the Mausoleum at Harris, having sold the whole island, save for the Mausoleum, but including the castle and its contents, to the NCC in 1957 for the ‘knock-down price of £23,000’ on the understanding that it would be used as a National Nature Reserve.

The NNR

In 2010, SNH handed over Kinloch Village to the Isle of Rum Community Trust to provide land for housing and local enterprises. The island still is owned and managed as a single estate by the NCC’s successors, Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH). In addition to its status as a NNR, Rum was designated a Biosphere Reserve in 1976, a Site of Special Scientific Interest in 1987, and has 17 sites scheduled as nationally important ancient monuments.

The Rum NNR was originally envisaged as an ‘open-air laboratory’ with scientific research conducted into specific areas of the island’s ecology, most notably the long term study of the red deer population. Rum was also the primary site for the ultimately successful reintroduction of the white-tailed eagle to Scotland during the 1970s and 1980s. However, SNH has shifted the emphasis to re-creating a habitat resembling what existed before the island’s native tree cover was removed. This has involved the reintroduction of over a million trees and shrubs of 20 native species in the vicinity of Kinloch and Loch Scresort.

Magnus Magnusson’s well-regarded book on Rum is entitled Nature’s Island – an apposite description of this mountainous island wilderness, where it is easy to imagine a past without much human presence. However you can also revisit the isle’s more decadent human past at Kinloch Castle.

Wildlife

During the autumn rut the night air on Rum resounds with the ‘belling’ roar of stags (photo: Konrad Borkowski)

Rum’s red deer population has been the subject of a long term study by researchers from Cambridge and Edinburgh universities, based at Kilmory Bay in the north of the island. The research has focussed on the sociobiology and behavioural ecology of red deer. The island’s deer population was hunted to extinction in the 18th century, but since reintroduction in 1845 the number has grown to the currently maintained level of around 1500.

Red deer near Guirdil bothy

The island has a small herd of about 14 ponies. The Rum Ponies are an old breed, and their presence was first recorded in 1772. Shortly thereafter, Dr Johnson described them as ‘very small, but of a breed eminent for beauty'. They are of stocky stature, averaging 13 hands height, with a dark stripe along the back and zebra stripes on the forelegs. These features suggest that they are related to primitive northern European breeds, perhaps introduced by the Norsemen. It is sometimes claimed – erroneously – that they are descended from animals off-loaded from ships of the Spanish Armada. The ponies are used to bring deer carcasses off the hill during the stalking season, but are otherwise left to roam wild.

Rum’s wild goats are subject to the same Armada myth as the ponies, but are in fact descended from domestic animals. The goat stocks were improved for stalking during the Bullough’s tenure and were renowned for their impressive horns and thick, shaggy fleeces. The tribe, numbering around 200, usually inhabits the sea cliffs and mountains, particularly in the west. A small herd of around 30 Highland cattle was introduced to the island in 1970.

Atlantic grey and common seals frequent Rum’s coastline, and Eurasian otters patrol territories around the island’s shores. Other mammals found on Rum include the pygmy shrew, pipistrelle bat, brown rat and the island’s own strain of long-tailed field mouse, Apodemus sylvaticus hamiltoni. The only reptile found on Rum is the common lizard, and the only amphibian is the palmate newt. There are brown trout, European eels and three-spined sticklebacks in the streams, and occasionally salmon in the Kinloch River.

Rum is renowned for its 61,000 pairs of Manx shearwaters – one of the world’s largest breeding colonies. These migratory birds return to Rum every summer to breed in underground burrows high in the Cuillin. Trollaval has high densities of nest burrows, which may have been occupied for many centuries. When the birds swap incubation shifts at night they make a fearsome racket, hence the Norse name for the mountain. There are sizeable colonies of fulmars, shags, guillemots, razorbills, kittiwakes and other gulls, mainly found along the south-eastern cliffs.

White-tailed eagles were persecuted to extinction on Rum by 1912 and became extinct in Scotland thereafter. A programme of reintroduction began on the island in 1975, and within ten years 82 young birds from Norway had been released. Today a successful breeding population is gradually colonising the west coast of Scotland. Several pairs of golden eagles nest on the island; merlin, buzzards, sparrowhawks, peregrines, kestrels and short-eared owls are the other resident birds of prey. Other bird species include the red-throated diver, red-breasted merganser, eider, shelduck, red grouse, corncrake, oystercatcher, lapwing, golden plover, curlew, cuckoo, raven and hooded crow as well as various finches, tits, chats, thrushes, warblers, pipits and wagtails.

Invertebrates include numerous species of damselfly, dragonfly, beetles, butterflies and moths. Several rare species are found on the slopes of Barkeval, Hallival and Askival including the ground beetles Leistus montanus and Amara quenseli. The hugely irritating midge (Culicoides impunctatus), a small biting gnat, occurs in unbelievable numbers between mid-spring and mid-autumn. Deer ticks and clegs – an aggressive horse fly – are the island’s other bloodthirsty beasties. Ticks can carry Lyme disease, which can become seriously debilitating if undiagnosed and untreated.

Woodland, Plants and Flowers

By the end of the 18th century much of Rum’s woodland had been cleared for grazing. John Bullough planted 8000 trees at Kilmory, Harris and Kinloch in the 1890s, but only some of those at Kinloch still survive. In 1960 a nursery was established at Kinloch to support re-introduction of 20 native tree species, including Scots pine, oak, silver birch, aspen, alder, hawthorn, rowan and holly. Over a million native trees and shrubs have since been planted. The forested area is limited to the environs of Kinloch, the slopes surrounding Loch Scresort and on nearby Meall á Ghoirtein.

As a consequence of high rainfall and acid soils 90 per cent of Rum’s vegetation comprises bog and heath. Much of the island is dominated by tussocky purple moor grass and deer sedge. In boggy areas sedges and bog asphodel abound alongside sundew and butterwort. Heather or ling (calluna) occurs in drier areas. The well-fertilised soil beneath the Manx shearwater burrows in the Cuillin keeps the turf green at an unusually high altitude.

Among the island’s other flora are the rare arctic sandwort and alpine pennycress, endemic varieties of the heath spotted orchid and eyebright as well as more common species such as blue heath milkwort and roseroot. A total of 590 species of higher plants and ferns have been recorded on Rum.

Getting Around

Visitors are not permitted to bring vehicles to Rum and there is no public transport on the island. Getting around on foot is the norm for most visitors, although mountain bikes can be of use on several of the island’s Land Rover tracks.

Amenities

Signpost, Kinloch

The Isle of Rum General Store is situated next to the village hall and stocks bread, fruit and veg, tinned goods, some frozen meat, beers, wines and spirits. Groceries can be pre-ordered with three weeks’ notice; tel: 01687 460328. The island’s Post Office is at the shop. The village hall has a tearoom – open between 10am and 4pm daily, serving hot drinks, soup, toasted sandwiches and home baking – public toilets, internet access, a pool table, dart board and a sitting area facing the bay. There is no shelter at the pier.

Kinloch Castle houses the island’s hostel and bistro; however at the time of writing (2011) it appears likely that SNH will close the hostel within a few years. The hostel is in the former servants’ quarters. Breakfasts, dinners and packed lunches are available. There is a well-equipped communal kitchen for self catering. The bistro is open to non-residents but takes advance bookings only. The Courtyard Bar is open daily from 5pm to 11pm and Sundays 6.30–11pm and serves beers, wine, spirits, soft drinks and savoury snacks. Postcards, castle guidebooks, midge repellent and Orchestrion CDs are available for sale at the castle, and in summer there are daily tours of the principal wing of the castle, a time capsule of exotic Edwardiana. Guided tours last an hour and in summer 2011 cost £7 per adult and £3.50 per child.