Читать книгу Last Chance Texaco - Rickie Lee Jones - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Juke Box Fury

My mother, Bettye, and my nieces

My mother was raised in orphanages around Mansfield, Ohio. Her parents, James and Rhelda, were unable to care for her. The Glens were a clan who ran full on at life and just kept going.

My maternal grandfather, James Glen, was the youngest boy in a family of women and a doughboy in World War I. He survived the terrible Battle of Argonne, in France, where mustard gas was used on soldiers. Family lore claims he was badly damaged by the gassing, and for the rest of his brief life he drifted, jobless. I don’t know how he felt about his children. There was only one encounter between James and my mother. There are no pictures of him. He died of tuberculosis while my mother was still a teenager, and I do not know if anyone came to his funeral.

James Glen returned from the blown-up fields of France and against his family’s wishes, married a teenage girl, Rhelda “Peggy” Rudder. Together they made four children in rapid succession: Don, Fritz, Jimmy, and Betty Jane, my mother. Peggy was Dutch and French, her people were poor. Peggy’s mother, Ora Issey Spice, had no hand to lend her wayward daughter, and no husband to bring in money. I recall the story of the great grandfather who bought one of the first automobiles in the county and crashed it trying to avoid a rearing horse and buggy. His Airedale dog, dismayed and confused, would not let anyone get to the dead man in the driver’s seat and had to be shot by the sheriff.

Other than her remarkably musical name, Ora Issey Spice was absent from bedtime stories but she did have a brother named “Hangman” whom mother spoke of from time to time. “Did he hang people, Mama?” Nope. Just a nickname (I hope). Uncle Hangman was a diabetic who had to shoot himself up with an old blunt needle that would hardly penetrate his skin. He was too poor to afford a new needle.

Grandmother Spice’s family were pioneers, turn-of-the-twentieth-century Americans who “combed their teeth with a wagon wheel.” Born in the late 1800s, my great-relatives worked their way across this young country. They had no running water, no electricity. Funny, it wasn’t much more than a hundred years ago they were all just kids. Now they are weeds in the wind, a trickle down your back.

Life is a locomotive, and as long as you watch it from a distance it takes a long time to go by. Ride that train and you’ll be gone in the blink of an eye, the landscape moving with you.

“Night Train”

By the time Grandma Peggy was twenty years old she had three children and was fending for herself while Grandpa Jim was camping out in the fields of Ohio. He lived as he did back in France, sleeping under trees and building campfires. He never fully returned from the war. In one of those fields near a farm that had just been robbed of some chickens, the sheriff found Grandfather roasting a bird under the stars. The judge sentenced him to a year in prison for stealing chickens, and while Jim was in prison, Peggy gave birth to their fourth child, a blue-eyed girl named Betty Jane. My mama.

With James Glen in jail, Richland County officials took a personal interest in the Glen children. They removed all three sons from Peggy’s custody, but for the next few years Peggy managed to elude the authorities and keep her baby girl. She’d already lost her boys and her husband—she was not letting go of her daughter for anybody.

Baby Betty was sleeping in Peggy’s bedroom when the social worker came to take her away to the orphanage with her brothers. The social worker had official papers and a police officer with her as she pounded on the front door. Peggy hurried to the bedroom and gathered up my mother and climbed out the window. Peggy went a-running as fast as she could through the cornfield with my mother in her arms, leaving the social worker still standing on the porch. The social worker took Peggy’s flight personally and would pursue Peggy as if Betty were her own child.

I heard this story of Peggy running through the cornfield so many times that it became my story, too. I was there—inside of my mother’s skin as her mother ran for our lives. My daughter, too, somewhere inside of me. We all ran across the cornfield with my grandmother.

Peggy lived on the run. She found an apartment and a roommate and worked as a waitress to take care of my mama. She always looked over her shoulder because Richland County and the social worker would not give up. There were close calls as they kept on coming for her.

One evening, Peggy was waiting tables while her roommate was sitting with the baby. Betty-nanny was in the apartment watching the sandman floating by sprinkling baby-light magic on her blue and quiet eyes. There was a knock on the door. Peggy’s roommate answered and came face-to-face with the social worker looking for Peggy and her child. “Peggy is not here. She’s at work. You go on and get outta here now,” and she closed the door. The social worker was employed by the devil himself and would not be deterred by words. This time she went around the back of the house and climbed in through the window, grabbed little Betty, and climbed back out and ran. The social worker kidnapped my mother.

It was a harsh time in America and Peggy had no husband at home to make her “legitimate.” She never had a chance to win her children back. The courts ruled Peggy an unfit mother and all four of her children were permanently separated from their mother’s care. The Glen kids, along with a million other orphans of the Great Depression, were left to fend for themselves among the religious fanatics and pedophiles and sadists that seemed to gravitate toward children’s homes.

At least the Glen children had each other at the orphanage. Their bond was unusually strong, their word true. In a crucifix of rhyme and spit, each one vowed not to be adopted if it meant being separated. By swearing faith to one another they created an extraordinary sense of integrity for their family and future families, although this promise condemned each to a childhood of institutions. “Night Train” belongs to the women of my clan.

Here I’m going

Walking with my baby . . . in my arms

Cuz I am in the wrong end of the eight-ball

And the devil is right behind us

And the worker said

She’s gonna take my little baby, my little angel, back

But they won’t get ya, no

Cuz I’m right here with you

On the Night Train . . .

My mother’s stories are the heart of me, the country from which I come. Escapades of her ghastly childhood in the orphanage were the Grimm’s Fairy Tales of my own. Trolls and dragons could not compete with my mother’s impossibly gothic reminiscences of the 1930s and the orphanages where she grew up.

Many nights, lying there with my mother (Father was always at work) my brother and I would ask Mama to tell us one of her stories. Of course we knew them all by heart, or at least we thought we did, but we’d ask for them like you might ask someone to play a song. Play that one, Mother. Tell us about One-Ball!

One-Ball

Of all the people Betty Jane met—the nice cook who baked her a cake when she was twelve, or the kind, young couple who bought her new clothes and gave her a private room of her own (and then returned her to the orphanage because she refused to live there, separated from her brothers)—Mother recalled the matron, “One-Ball,” with the most chortles and disdain. One-Ball alone received a name from the orphans—one worthy of her half-human heart.

One-Ball was named for the solitary ball of hair, the bun, she pinned up on her uncommonly cruel head. It was speculated among the children that the name more likely referred to the one testicle she hid up there under her skirt, thus, “One-Ball!” My mom would laugh so hard about that. Lying with us, thirty years away from that orphanage, it was finally safe for the little girl inside her to giggle out loud.

One-Ball liked to sneak up on kids, trap them, catch them as she hid in a shadow holding a belt. It was the surprise element that was the sadism. She kept children in a constant state of terror and exhaustion. After years of silent acceptance, my mother finally confronted her tormentor, redeeming a lifetime of torture. Old One-Ball almost ended up No-Ball-At-All. If you get my meaning.

Mother had her own bedroom now, being fifteen years of age; she’d earned her privacy after thirteen years in orphanages. On this particular evening, One-Ball, bored and restless, was scouting for an unguarded child to pounce on, and stealthily she entered my mother’s bedroom. Betty was seated at the vanity, brushing her hair with her back to the room. One-Ball hoped to grab her by the hair—the element of surprise brought the terror that was so satisfying. Mom spotted One-Ball in the mirror and she kept her cool, waiting until the old witch was nearly upon her and then she rose suddenly, with her hairbrush raised in the air. This time it was One-Ball in the hot seat.

Mother faced her tormentor. “If you ever sneak up on me again, try to hurt me, even touch me, I’m gonna ram this hairbrush down your throat and it’s gonna come out your butt.”

Bold move, Mom. One-Ball staggered, her soul shrinking, and retreated like a demon caught in its own reflection. One-Ball did not catch my mother that week or any other, ever again. She was a bully and bullies can only eat the fearful.

One-Ball went into the shadows from which she came, just a page or two in a chapter about the cruel adults who abuse little children. Gentle Betty, it seemed, had been waiting for a chance to strike a blow for the little guy. Literally. Mother’s years as a slave were coming to an end. She would be gone by her sixteenth birthday.

Even though her nickname was “Sarge,” my mother’s demeanor was unconfrontational, and something way inside—the little girl she was once—was exceptionally kind. It was there till the very end. Like an iceberg, I suspect most of my mother remained frozen under the surface. She would often demand:

“What’s the use of bringing all that up?”

And she was right. All that hand-wringing and chanting of unfortunate memories, what’s the point of it? Cry your tears and be done with it. My mother—and my mother’s past—is always with me.

Rhubarb Pie

Mama had the most secrets and the best poker face. It was forty years before I even knew she played the piano! One evening near Christmas Mom sat down and played “O Holy Night.” My mouth fell open, and my little sister and I sat silently in awe. Who knew what else she kept in that caldron of cakes and pies and blood and tears?

For Mother, the lesson of orphanage life was simple: control yourself. Mom started the rhubarb pie story with a different twist on this lesson every night: never let them know you like it or they’ll take it from you. Which was another way of saying never let them see who you really are. Tom Waits used to say that, too. I never listened to either of them.

The rhubarb pie story is a testament to that one truth, and the reason behind my mother keeping so many secrets so well.

“We hardly ever got to have dessert, and rhubarb pie, they only made it for the kids once or twice a year. It was my favorite. We were lined up to go into lunch and as we entered I saw the pie on the table. I was so excited that I gasped, like this”—she sucked in air—“One-Ball heard me and pulled me out of line. They sent me to my room without any lunch.”

“No pie?” I asked.

“No dinner, either.”

She explained, “It is hard for little kids to stand still, especially when they’re excited about dessert. Jim just couldn’t seem to stand still. The male guards were much crueler than the women—they liked to flick Uncle Jim’s ear, they knew it hurt him so bad. He always had ear infections. They hit his ear to make him cry. They said it was to teach him to stand still but it was really because they just liked to hurt the children.”

As with the flicking of Uncle Jim’s infected ear, the staff customized punishment to uniquely hurt little children and leave a mark on them into adulthood. The little girl who loved rhubarb pie was still in my mother’s voice as she relived the despair of inexplicable cruelty.

For Mother’s seventieth birthday, I bought her a giant rhubarb pie. It was big enough to feed all the children in the orphanage: Jim, Don, and Fritz, and all the rest of them. They are ghost orphans now. I could not reach them with my pie. I thought to shine a kindness so bright that it would shine into her past, but we can never undo what was done.

Ninety years ago, my mother’s entire generation was tricked into the dust bowl of desperate poverty called the Great Depression, due to the greed and narrow interests of wealthy men. Betty’s sad childhood as an orphan was so common that Little Orphan Annie, a syndicated comic strip character, became a national sensation. Child actor Shirley Temple, one of the biggest box-office stars of the time, usually played a singing, dancing orphan of some sort. In 1932, my mother’s image became iconic. She got her first job as a model at three years of age, in a print ad for cake flour. She was the image of a happy child, her Dutch-boy haircut neatly framing her sweet face, her tiny fingers almost touching a yellow cake that would always remain beyond her fingertips.

My song “Juke Box Fury” opens with a little introduction, a melody my mother often hummed around the house. It was the only song I remember her singing regularly. She said it was already old when she learned it as a little girl. Dorothy herself probably sang this tune on her way home from Oz:

Polly and I went to the circus,

Polly got hit with a rolling pin,

We got even with the circus,

We bought tickets but we didn’t go in.

This melody made a powerful impression on me. It told me everything I needed to know about my mother’s America. “Ain’t got nothin’ to prove to nobody.” Perhaps, then, this song is the proper title for the last and saddest of her stories—though not the most violent or most tragic. Just . . . another ticket unused.

A Bum on the Bench

My mother’s father, James Glen Sr., was a “red-haired-blue-eyed-Irishman.” She liked to rush through to make that collection of syllables into one word. When Jim got out of prison, he was sick with the same tuberculosis that would kill both my grandfathers and a generation of Americans. Had the media reported my grandfather’s death they might have said, “A veteran of a war long forgotten died before his time in a VA hospital somewhere near a chestnut tree and a wishing well.”

He was an old man by the time my mother was fourteen years old, but very, very shy Betty agreed to meet him. She was an excellent student, and so serious about her gymnastics that she wrapped her bosom to flatten her profile. She wasn’t totally sure she wanted to meet the old man. What if she didn’t like him? What if he didn’t like her?

Betty’s brother Jim Jr. arranged for them to meet in a park. “Walk through the gate and to the left, there is a statue and a fountain. Dad will be sitting on the bench by the fountain.” She arrived after school with her books in her arm, something to hold onto or place between her and him. She sat down on the bench to wait.

When she bent down to tie her shoe she noticed an old man, a bum, sitting to her left. Had he been there all along? She let her eyes meet the man’s. He was looking at her. Then he grinned, a mostly toothless smile. Why was he smiling at her? She shuffled, tried to look away. It was hard to breathe, she was such a shy girl. Then the old man took off his hat. It was the red hair, the famous red hair.

She realized, Oh God, it was him.

Her father rose slowly and sat down next to his daughter. “Betty Jane?” And he smiled, so big, so happy. “I’m your daddy.” He had no front teeth and he looked like a poor bum in old clothes and worn-out shoes. Betty Jane stood up and ran away, crying. Her father watched her go. He put his hat on and walked back to wherever he came from. Her brothers chastised her. What was she afraid of? An old man? She would never again see her father. He died of TB shortly afterwards.

The Orphanages of Richland County

This orphanage relied on the work of children to turn a profit, but the children didn’t get much of the food they harvested. The four Glen kids, my mother and her brothers, were behind the main house, shucking corn. There was a big pile of it, and six-year-old Betty pulled the sleeves off, then removed the silky golden “hair” and put each ear of corn in a tin pot. Her older brothers were nearby, gathering up old stalks of corn; the eldest, Don, standing by, pretending to help. Mother said the kids got the parsnips and turnips and only rarely (on Sundays), chicken (necks) and dumplings.

The Glen kids had decided to run away, again. The eldest boys, Don and Fritz, whispered to seven-year-old Jimmy, “We’re gonna run today. Be ready.”

“What, run? Now?”

“You’ll know.”

When old Mr. Brown or Miss Smith went into the smokehouse, the kids took their shot. Don and Fritz lit out across the cornfield.

“Come on!”

Jimmy grabbed ahold of Betty’s left hand and ran after them. Don looked back to see Jimmy losing ground. Mr. Brown was already out the back door and running across the field, so Don slowed down and reached for Betty’s right hand. Now Fritz picked up the slack and took his sister’s hand from little Jimmy, the two bigger boys pulling her behind them. Betty was lifted off the ground and she flew between her brothers like a kite. In my child’s mind I would see her up there, the wind lifting her body, floating heavenward and away as the Glen family, racing for their lives, showed my mama how to fly.

Everyone was a-runnin’ as fast as they could but Don could see they were still losing ground. The old man Mr. Brown called for help (“Goddamn Glen kids”) and now there were a number of adults trying to head off the Glens. Wisely, Don and Fritz dropped Betty’s hands and she tumbled to the ground. The two of them ran like horse thieves. If Mr. Brown caught him this time, Don knew he was gonna regret ever having been born.

Betty raised her head, calling to her brothers, “Wait for me!” but she would soon learn to accept defeat wordlessly. Never let them see you cry. Jimmy was still running but he was only a year older than his little sister, and he couldn’t get far. He cried out as the men yanked him up. One of them slapped Jimmy on his sore ear. Jimmy and Betty were taken back to the big house and sent straight to bed without supper. Jimmy was small but since he was a boy, he was whipped. Betty was not hit, not because she was too little to beat but because she really had nothing to do with what had happened. Well, maybe a swat or two just for being in the fray.

Sacrificing Jimmy and Betty to the chase allowed Fritz and Don to escape. They were hiding in a ditch making profound social calculations that no child should ever face. Don said, “Hell, they won’t hurt Betty because she’s just a baby. They might spank Jimmy but if they catch me they’re gonna beat me to death. I ain’t a-gonna be beat no more.”

Years later, as I asked about the orphanage punishments, I remember my uncle Don grinning:

“The way they beat me, they like-ta killt me,” and his smile hesitated as if he recalled something that was not smiling back. A flicker of pain. Then he was back to his charming, polyester-leisure-suit self.

Uncle Don, trying to jump-start a ranch of his own, once stole a semi-truck filled with cattle heading for Bob’s Big Boy restaurant. He got caught and went to prison. I confess I enjoyed the dichotomy of twentieth-century-style cattle rustlers in semi-trucks. A certain family pride.

Don and Fritz finally made their way to Chicago where their mama lived. They were outside the State of Ohio’s budget, and “Just let ’em go” finally echoed down a government hall. Don eventually returned to Ohio and bought a house near Wooster. He married a nice Italian lady and they offered their home to kids who needed foster placement. Fritz married a stripper and ended up in Waco, Texas.

When Mother finally left the orphanage in 1944, she headed for Chicago and was reunited with her mother at last. She moved to the North Side, went to secretarial school, got a job, and started spelling her name with an “e” at the end. Bettye. It was the first inkling of her determination to make herself into a new person. Released from the region, she would eventually free herself of that southern Ohio/Kentucky accent that might forever brand her as “un”—untrustworthy, unworthy, and unsophisticated.

Bettye was full of life and energy, the world laid out before her. She planned to stay single until she was at least twenty-eight years old. She wanted to see the world, to be somebody. She would be anybody except what the orphanage had confined her to.

My parents met at a lunch counter where Mother and her roommate often stopped for a quick bite before going to work. My father, the waiter, was classy. He was dark and brooding, back from the war, and handsome like a movie star. Like most World War II veterans, he drank and fought and laughed about drinking and fighting. They took a trip to Florida together before we were born. I only know this because I once asked where a photograph of Mother was taken. She was private, even secretive, so most of her pre-Rickie life went with her to the Invisible World of the Great Beyond.

Bettye was twenty years old when she got pregnant. She wasn’t married. I had suspected this as a child but had been rebuffed with great condemnation—how dare I imply such a thing. One day she accidentally revealed it during a conversation when I was at least forty-five years old.

“Oh, didn’t I ever tell you that?”

“No! Motheeeer! I asked you when I was a kid about that and you scolded me for asking!”

“Close your mouth, you’re catching flies. It was none of your business. I guess you’re old enough now to hear.”

Mother’s life with my father, who also bore the scars of a life without a home, was premised on a vow that they would make themselves into better people than their ancestors. They were determined to jettison their past lives and join a better stratum of society.

My parents married and lived in Chicago for the first four years of my life. My sister Janet (eight years older) was attending school in a Catholic convent and my brother, a little soldier, attended a Catholic military school. Janet had some trouble on her vacation back home, and my father decided we had had enough of Chicago. Shortly after my fourth birthday celebration at kindergarten, we said goodbye to the Windy City and hello to the road. It was the siren call of the West.

Mom and Dad thought that together they could do anything because anything was possible with money and they had a strong work ethic. Together they worked two jobs each and double shifts as often as they could. They saved their money. Their son Danny would go to college, study law, maybe become the president of the United States. Anything was possible with hard work.

But my parents had learned as kids to avoid government, big institutions, and authority. They used cash to avoid declaring income and they avoided obligations beyond next month’s rent. Their mistrust extended even to census takers, so banks and mortgages were out of the question. They pushed themselves hard but never accumulated wealth.

Once they left Chicago they never stopped moving. What were they running from? Well, they ran from cities, houses, and eventually themselves, but they never got away from their difficult childhoods or their love for each other. Long after their lives together ended, my mother would stare at the window tapping her foot as if she longed for the music Father brought to our house. My father missed Bettye’s jitterbug dancing. She was a very good dancer. I oughtta know, she taught me to jitterbug one rainy afternoon in my brother’s log cabin out in Lacey, Washington. We were listening to Van Morrison’s “Jackie Wilson Said.” Mama swung me around like a redheaded stepchild. She knew how to lead alright, because she’d grown up following.

Childhood traumas leave their dirty footprints in the fresh white snow of our happy-ever-afters. No matter what my mom did—or her brothers, for that matter—she found traces of her past obstructing her future. She built a better life but didn’t escape her past. Orphanage children received clothes and schooling, but not love and affection. They had food where others in the Depression did not, but even this privilege came at great cost, for it could be withheld on the whim of an employee. In this torment, my mother learned not to hold onto the things she loved because then no one could take them away from her. Our violent past will also find our children. It echoes. Recovering takes generations.

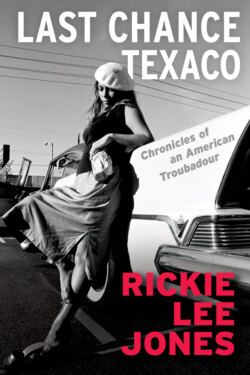

Betty Jane poses with cake