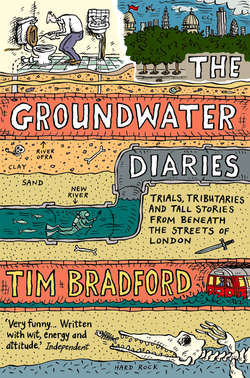

Читать книгу The Groundwater Diaries: Trials, Tributaries and Tall Stories from Beneath the Streets of London - Tim Bradford - Страница 7

2. Special-Brew River Visions (No Boating, No Swimming, No Fishing, No Cycling)

Оглавление• The New River – Turnpike Lane to Clerkenwell

Invisible rivers – Sex File – magic glasses – more dream analysis – in the library – Turnpike Lane – Clifford Brown – Patrick Swayze in Albanian Ladyboys – Finsbury Park – Woodberry Down – Swedish prisons – Highbury Vale – Clissold Park – Canonbury – Islington – Clerkenwell – Special Brew visions – the floods

Another dream. I’m walking along the bank of the New River in the park with my wife and daughter. The path is very narrow and the water is full of crocodiles. We start to throw golf clubs at them (irons, not woods) to stop them climbing onto the bank. I throw the whole bag in and tell the others to run for it.

London is a city of invisible boundaries. Areas alter in atmosphere or architecture in the space of a few yards, and a reason for this might be that the rivers which once flowed were often the borderlines between ancient parishes and settlements. You might walk down a street now and suddenly notice a change in the air. Chances are you have walked across the course of an underground river. The New River would have been no different. Although a recent addition to the waterways of London (about 400 years old), when it was built it would have run through mostly open countryside and settlements would have grown around it.

Some portions of the New River are visible to the naked eye. Yet these sections (for instance, Turnpike Lane to Finsbury Park), which flow silently behind housing estates and terraced streets, seem somehow not as alive as those which have disappeared. It’s the ghost parts of the river, now covered by houses, gardens, shops, parks and roads, that get me going more than the algae scum1 cuts I can see filled with bikes, shopping trolleys and empty plastic Coke bottles.

Searching for lost rivers is, in a way, a spiritual journey, searching for things that I once valued but have lost, like my Yofi acoustic guitar, God, my grandfather’s retirement watch, a sense of childlike wonder at the universe, old girlfriends’ phone numbers, a large cardboard box containing copies of the New Musical Express 1979–82, and my Sex File. Actually, my Sex File, one of the Really Big Things in my life that was truly lost (or, rather, forgotten about – it’s often the same thing) – a pink four-sided A4 folder plastered with pictures of models from a stolen late-seventies edition of Playboy, with notes and drawings (and even coloured in areas) by me – was recently rediscovered by my father. He found it folded up in an old cobwebby red-brick chicken shed in the field behind the family house, where it had lain untouched (except by spiders) for over twenty years. The Sex File was a snapshot of my early teenage desires and fears, in many ways a mystical (almost religious) document – sort of like an East Midlands Dead Sea Scrolls but with leggy blondes, huge breasts, erect nipples and adverts for penis enlargers.

Before I could track the exact course of the New River I needed to do some research at my local library. However, I was immediately faced with a problem. I wouldn’t be able to take any books out because I was currently a library Non-Person as I had a couple of books that were seven months overdue. One was an earnest tome about water spirits (the author had apparently lived with the spirits for several months and had been accepted as one of them), the other a teach-yourself aikido manual written in the fifties.

Aikido is a jolly nice way to get fit and beat up chaps who are giving you a hard time or staring at your wife. Rather than going into the ring with them you simply give them a couple of hefty aikido chops and, hey presto, their nose cartilage has been pushed up into their brain and they’re stone-cold dead! Crikey! You’ll be the talk of the Lounge Bar. I say, old chap, here come the rozzers. Remember, this is the fifties. The forces of Law and Order don’t take kindly to fellows who are dressed up as Chinamen. You’d better leg it, old man. Aiiee banzaaai!

The Gentleman’s Guide to Aikido

To go with my new habitat I also had a new look, a pair of mid-seventies National Health glasses. I’d originally got them when I was thirteen but never used them, having been anxious in my early teenage years to appear both tough (to stave off the hard cases who roamed the playground like carnivorous dinosaurs with feather cuts) and cool (to try and impress just one of the many girls I fell hopelessly in love with every week). Janus-like, I looked in two directions, at the birds and the bullies. Pity they weren’t in focus. Like the Sex File, the glasses had been forgotten about for a couple of decades until I recently found them at the back of a drawer in my parents’ house and brought them back to London. Now I wanted to reclaim my swottishness. If I hadn’t been so hung up on not being beaten up and getting a snog I would probably have been a pupil who enjoyed learning (‘Ha ha, not really, Togger. Only joshin’, mate!’) Now I was going to recreate the Anal Years and spend weeks in libraries. The National Health specs would give me the vision of an inquisitive and swotty thirteen year old. Without the spots, the Thin Lizzy albums and the contraband porn mags.

Leaves were already blowing across Clissold Park. The skies were now grey and heavy. Then, just as an autumn melancholy was descending over north London, summer started up again, with muggy days and tropical drizzle and dragonflies dancing around the park. Then came a full-blown three-day heat wave while all over the country irate lorry divers were picketing garages due to a petrol shortage. A sense of unreality was in the air, culminating in England winning a cricket series against the West Indies. Then the rains came again.

An email arrived from Keith the online dream analyst:

Water in dreams is a consistent symbol for emotions. (Some people speculate that our first emotional memories are created when we’re still floating in our mother’s wombs. This may explain the correlation between water and emotions.) Accordingly, floods and tidal waves and other dream visions of rising water usually are associated with periods of ‘heightened’ emotion in our lives.

Keith

This was getting annoying. Keith the online dream analyst hadn’t analysed my dream – he’d completely ignored the stuff about crocodiles and golf clubs. This highlighted a major problem with the online world. Things don’t get done properly and you, the consumer, have no come-back because even the biggest corporations are actually run from some student bedroom in the LA suburbs. With razor-sharp clarity I realized there was only one way to sort this out – go to a better and more expensive online dream analyst.

More rain. The old tree-covered New River embankment in the park was dotted with pools of murky water. Beneath some of the trees were clusters of magic mushrooms. A few years ago I would have been tempted to pick them to find out what strange dreams the river might offer me. Now, my drug of choice was a strong cup of tea. Maybe with a biscuit. While splodging around at the edge of the park I noticed that the gate to the little Victorian pump house was open and I just had to peek inside. Expecting to find lost and magical artefacts relating to the New River’s past, I found only empty cans of strong lager and cigarette packets. I stood in the building trying to imagine what it would have been like 150 years ago, but all I could picture was a couple of blokes in tatty leather jackets with beetroot faces swearing at each other. I then walked to Stoke Newington Library and sat there surrounded by books on London, place names, rivers, architecture. For the first hour I flicked through free leaflets on yoga and local arts courses, then read the papers. The other people, mostly old or worn-out looking folk and the odd goateed library employee, seemed to be there because they didn’t have anything else to do. But not me. No, ha ha, not me.

(Adjusts National Health glasses) When James VI of Scotland arrived in London in the hot summer of 1603 to be crowned King of England, he soon discovered to his horror that his new capital had a foul and unhealthy water supply. Most of the city’s medieval wells and streams had been used up and the water in the larger rivers was undrinkable. The largest of the tributaries, the Fleet, was little more than an open sewer, while the Thames was also, literally, full of shit. Small-scale conduits were piped in from outlying villages such as Paddington, but these had little impact on the now rapidly rising population. James knew that something had to be done quickly because he was thirsty.

After my first book Is Shane MacGowan Still Alive? was published in the spring of 2000 I began to consider the idea of myself as Travel Writer. Travelling, jotting things down on the back of beer mats and being paid for it seemed too good to be true. Emboldened, I decided to embark on my second book. One idea was provisionally titled Heartbreak On The Horizon, a sort-of-travel-book about (me) trying to make it as a country music songwriter, incorporating my experiences in a group which once nearly supported Eric Random and the Bedlamites at Nottingham Ad Lib Club.

However, I’d also been plugging away on a book about my experiences of London. It had developed from a novel I’d written in 1988 about tai chi film-buff bikers, set in and around a squat in Leytonstone (with free jazz, Leeds United and the history of the pullover thrown in) and had entered in the P. G. Wodehouse Comic Novel competition. After getting the rejection slip back I buried it in a field somewhere – I still get backache just thinking about it. Now I dusted down the idea. Travelling in London seemed more intriguing than roaming the planet in search of the exotic. The stuff happening at the end of any street in London is far more interesting than, say, the antics of someone stuck on a didgeridoo farm for a year. The idea of finding mystery and adventure on the other side of the world has been hijacked by the tourist industry and TV travel shows. There’s nothing new to find out there so people are turning in on themselves and looking for enchantment closer to home, looking at the things they’d forgotten about or possibly never even looked at. Like the Hare Krishna food delivery van parked across the road, the bloke at the end of the street who shouts ‘Grandad Grandad’ at the top of his voice every evening, the 125-year-old Greek woman who sits at the top of her front steps and waves to passers by. It was now obvious to me that my only course of action was to attempt a book about real life, a diary about my various journeys along the courses of the underground rivers of London.

Maybe I could do the rivers book and incorporate the country music stuff – get C&W stars to don wetsuits and swim in some of the subterranean water courses. For charity. Then record a concept album about the whole experience.

Using the old maps, I traced the course of the New River – as close as I could get – onto my A to Z. I had decided to start the walk just up the road in Hornsey, near Turnpike Lane tube, where the river reappeared after an underground stretch. There are also various sections further north – an original loop, an ornamental waterway, now flows around Enfield Town (it was replaced by a straight section of underground pipes in the thirties) and there’s also a section to the north of Wood Green. I took the Piccadilly line to Turnpike Lane, then ambled east along Turnpike Lane with its flaking Edwardian buildings, mostly small red-brick shops with awnings, selling fruit and vegetables, kebabs, the odd estate agent. It’s a tight squeeze. You almost have to move sideways to get past the people staring at the traffic, at each other, at that nowhere-in-particular place in the middle distance that many bored people look at. There also seemed to be some kind of work-for-all scheme going on – it took five people to transport a crate of satsumas or packet of toilet paper from van to shop and the pavement was full of blokes nattering to each other about the news of the day (‘Oi, Memhet, the bloke next door has got seven blokes outside his shop and there’s only six of us. We need another bloke – can we hire someone?’)

What is a turnpike? The name derives simply from a ‘lane beside a toll barrier’. Many of the major thoroughfares into London had these barriers, presumably to pay for the upkeep of the roads. However, whenever I hear the word turnpike I think of Clifford Brown, the jazz trumpeter who died driving off the Pennsylvania Turnpike. It sounds so much more glamorous than, say, smacking into the back of a bus near Turnpike Lane tube (it’d be the 341 or 141). That’s American roads for you. If there was a road in the US called the North Circular it would seem romantic and mysterious. We’ve all been brainwashed, somehow. Maybe through hamburgers or subliminal messages in rock ’n’ roll records and Hollywood films. They’re much better at that sort of thing than us Brits. Our idea of subliminal messaging is backtaping on LPs so when spotty fourteen-year-old introverts at boarding schools in the seventies played their Led Zeppelin records backwards they would hear stuff like ‘You must worship the deviiiiiiiiiilllll. If you are a girl you want to shag Jimmy Paaaaaaaage.’

I scrutinized the squiggly blue biro line I’d drawn in my A to Z. The section of the New River I was looking for was at the junction of Turnpike Lane and Wightman Road. The New River appeared not very majestically behind a high, half-rotten wooden fence crusted with barbed wire. It snaked from around a small housing estate into a bit of a straight.

Four years after James’s succession to the throne, his patience was at an end. The cleanest drinking water on offer in the capital, for which you had to pay good money, was now suspiciously brown. James invited some of his most celebrated engineers to consider solutions and think ‘out of the box’. In those days the phrase meant that if they didn’t sort it out they would soon find themselves in a box, six feet under.

There was an idea knocking about to build a man-made water channel that would bring in fresh supplies from the boring but clear-watered countryside of Hertfordshire to the north of the City. It was a madcap plan, but it needed someone with a posh-sounding name to bring it to fruition. Step forward wealthy Welsh goldsmith Hugh Myddelton, a man whose life so far had been a classic rags to riches story – young boy leaves the Valleys to find fortune in London, flukes a job at a jewellers in the City, works hard and gets own business, chosen by King to become Royal Jeweller. Myddleton not only offered himself up as the engineering genius to oversee the project but also put up the money as well (the projected cost was £500,000). Work began on the water channel – already called the ‘New River’ – in 1609, starting out at two springs at Amwell and Chadwell in Hertfordshire.

The New River, as if bored with hugging the main drag of Wightman Road, meanders off to the south-east between the houses of the Harringay Ladder, a row of long parallel streets than run down the hill to Green Lanes. I spotted an opening next to an old school and saw the river stealthily heading south. The path was inaccessible, with heavily bolted steel fences and Water Board signs telling people to keep out. I zig-zagged up and down a few of the streets just to peer over walls and railings to spot sections of the river, then walked down to where the river eventually crosses Tollington Road. Further down is the Albanian video shop and its window full of movies by Albanian Patrick Swayze lookalikes with film titles like I Love A Patrick Swayze Lookalike Ladyboy (possibly my translations are not 100 per cent correct).

At one point Myddleton ran out of money and asked the Corporation of London for help. He was refused so turned to King James who agreed to take on half the costs (and profits). Work was finished in 1613, the river ending at an artificial pond called New River Head just off Rosebery Avenue in Clerkenwell, from where water was distributed to houses in wooden pipes. Over its 38-mile course the New River had many long twists and turns as it followed the contours of the land to maintain the steady drop from Hertfordshire to London. The New River was hailed as a great success and Myddleton became a hero. Statues of him can be seen at various stages along the river’s route.

The river travels under the road and reappears in Finsbury Park where it snakes across the ‘American Gardens’. Finsbury Park is one of the few areas in this part of north London which doesn’t seem to have had the clean-up treatment in recent years, possibly due to the fact that three borough councils – Haringey, Hackney and Islington – are responsible for different parts of it. It still has, according to official figures, a higher proportion than most parts of London of crazy nodding people, walking around talking to themselves, staring in glassy-eyed gangs outside the tube station, bumping into you and asking for money, then looking forgetful and wandering off.

One of my favourite buildings in Finsbury Park was a music venue, The George Robey, a Victorian pub which in its time had been the birth place of many third-division punk bands (though no Danish ones) is now some kind of dance club with blackened windows, a fence surround and the ubiquitous ‘security’ hanging around.

As the wooden-sided river passes the cricket pitch and under a little bridge, it’s a bizarrely rural scene, a snapshot of how the whole landscape might have looked when the river was first built. Trees hang down over the banks, the water is clear. The river winds quickly across the north side of the park then disappears under Green Lanes, in the direction of the Woodberry Down Estate, where it disappears behind a fence and railings. Woodberry Down sounds like something from Rupert Bear. By all accounts it was actually like that (not the talking animals bit) until relatively recently – photos from 100 years ago show the New River meandering gently through water meadows past trees, stationary men with big moustaches and a little country cottage. The view is still good, though, and it’s easy to imagine standing on a gentle hill looking down into a green valley of farms and rolling fields, and across Tottenham and Walthamstow marshes.

Naturally there was a danger that, people being people, the New River would soon get clogged up with all the usual debris – shit, blood, pigs’ intestines, sheep’s brains, the rotting heads of traitors, bloated corpses of drunkards who’d fallen in, everything that at that time clogged up most of the waterways of the city. The New River Company decided to combat this by building paths on each side of the river and employing walkers, big burly moustachioed men who would patrol the river and have their pictures taken when photography was invented. These walkers had the power to fine or even imprison anyone they caught throwing rubbish or simply pissing into the river.

By the mid-nineteenth century most of the water supplies in London were once again polluted. The cholera epidemic of 1849 would eventually be traced to the contaminated water supply at Broad Street in Soho. Thanks to the New River Company’s vigilance, their water remained pure and drinkable but as a result it was too expensive for the poor of London. The philanthropist Samuel Gurney spotted a gap in the charity market and under the auspices of his new and snappily named the Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association, opened London’s first drinking fountain in Snow Hill, from water pumped (and bought) from the New River.

I cut across past Manor House, named after the old manor of Stoke Newington which stood nearby. Manor House is a big strippers’ and showbands’ pub, or at least it would have been in its glory days. I walk along the rumbling and dusty Seven Sisters Road for a quarter of a mile until the New River appears on my left looking very sad, chained up, covered in green American algae, another of those crap Stateside imports up there with grey squirrels and confessional TV, with a shopping trolley and plastic football set fast in the gunge. At Sluice House Nine (Kurt Vonnegut’s London novel), on Newnton Close, in the shadow of three big tower blocks, I am finally able to get back down to the river and walk alongside it as it winds past the East Reservoir, still covered in algae scum. There’s a sense of boundary here between the self-conscious bourgeois charm of Stoke Newington to the south – with the reservoir and trees, a church spire, Victorian rooftops, it could be the countryside – and the more uncontrolled and more recently built-up area around Seven Sisters Road to the right, a canvas of white council slab flats, shopping trolleys left upturned, kids playing football (two kids are trying to juggle a ball then the smaller of the two nicks it off the big one. The big kid knocks him over), an old people’s haven with three plastic benches like a prison. These tower blocks, another part of the huge Woodberry Down Estate, are quite spectacular.

The scheme had originally been planned in the early twenties when it was decided to get rid of much of the Victorian architecture in the area (Victorians hated Georgians, Modernists hated Victorians, we hate the Modernists – those fucking bastards), although not finished until 1952. Its four eight-storey slab blocks with projecting flat roofs in parallel rows were designed in a ‘progressive Scandinavian style coloured in the pale cream like Swiss municipal architecture’ according to the bloke in the little Turkish grocer’s shop across the way on Lordship Road.

The reservoir is a haven for birds and their human sidekicks, birdwatchers. Looking back, where the river meets the road, is my favourite view of the New River – a blanket of green covers a small sluiced section dotted with cans, blue girders, a red plastic football, aerosols and bottles coming up for air like gasping fish, the three identical tower blocks of Stamford Hill rising in the distance like silver standing stones. There’s ducks too, one old lad with four duck chicks – well, not chicks, they’re ducks, and one younger male with a dodgy leg who’s just been beaten up, probably in a fight over the duck harem, which waits in the background ready to change allegiance at a moment’s notice should the old fella peg it suddenly.

Across the road on Spring Park Drive is a fifties estate. A fat woman shouts out of a sixth-storey window to her daughter below, ‘Oi, get me some leeks.’

‘I don’t want to get leeks,’ says the girl.

‘Get me some fucking leeks, you little bitch,’ shouts her mum.

‘I don’t want to,’ says the girl and the mother is looking very, very angry. Get the leeks, go on, for a quiet life.

‘I don’t know what leeks look like anyway,’ the girl shouts up, then runs away. A right turn and there’s an old wooden bench on a patch of grass that once would have had old lads sitting down looking over the view, now it just looks onto the health centre. Look, there’s the window where they had the wart clinic. Ah, those were the days. Across Green Lanes again into the back streets and onto Wilberforce Road, with its rows of massive Victorian houses where there are always big puddles on the tarmac. Only 150 years ago all this area north of here up to Seven Sisters Road was open countryside with two big pubs, the Eel Pie House and the Highbury Sluice alongside the river, where anglers and holidaymakers would hang out. Then, in the 1860s, the pubs were pulled down and everything built over in a mad frenzy. If you compare an 1850s map of the district and the 1871 census map you can see the rapid growth of residential streets in Highbury and south Finsbury Park.

On Blackstock Road there are a couple of charity shops and a huge Christian place, all with great second-hand (or more likely third-or fourth-hand) record sections. Their main trade, however, is in the suits of fat-arsed and tiny-bodied dead people and eighties computer games (i.e. Binatone football and tennis – which is just that white dot moving from a line one side of your screen to another). They also have a fine selection of crappy prints in plastic gilt frames – mostly rural scenes, Italian village harbours and matadors. I buy a lot of crappy pictures in gilt frames and paint my own crappy pictures of London scenes over them, most recently Finsbury Park crossroads on top of a Haywainy pastiche. It’s cheaper than buying canvases and you get the frame thrown in too.

Now on Mountgrove Road, the old accordion shop is empty, the estate agents have moved, the graphics company has closed up, the electrical shop has been turned into flats. This was originally a continuation of what is now Blackstock Road, called Gypsy Lane, but it’s been cut off, like an oxbow lake. Cross over my road and you’re suddenly into very different territory – there’s an invisible border I call The Scut Line with cafés and corner shops on one side, nice restaurants and flower shops on the other. It marks a boundary of the old parishes of Hornsey, St Mary’s and Stoke Newington. The mad drunken people of Finsbury Park and Highbury Vale don’t stray south of the line, marked by the Bank of Friendship pub (‘bank’ possibly alluding to a riverbank). People would stand on one side of the river here and shout at the poncey Stoke Newington wankers – ‘Oi, Daniel Defoe, your book is rubbish!’

The course of the New River has been altered several times in the last 400 years. Originally it flowed around Holloway towards Camden, but in the 1620s it was diverted east to Finsbury Park and Highbury. Since these early days most of the winding stretches were replaced by straighter sections and its capacity was increased to cope with the capital’s increased demand for water. This meant taking water from other streams, to the fury of people whose livelihood relied on the rivers, such as millers, fishermen and fat rich red-faced landowners who just liked complaining. Later on, pumping stations were put up along the route which pumped underground water to add to the river’s flow. Until recently the New River still supplied the capital with drinking water, 400 years after completion. It’s obsolete now that Thames Water’s new Ring Main system is operational.

The river now runs only as far as the reservoirs to the north of Stoke Newington. South of here it’s mostly been covered over – this happened in 1952 when the Metropolitan Board of Works, eager four-eyed bureaucrats with E. L. Whisty voices, made it their policy for health reasons.

Across Green Lanes yet another time, past the little sluice house and the White House pub where skinheads drink all afternoon, and into Clissold Park. Originally called Newington Park and owned by the Crawshay family it was renamed, along with the eighteenth-century house, after Augustus Clissold, a sexy Victorian vicar who married the heiress (all property in those days going to the person in the family with the fuzzy whiskers). The now ornamental New River appears and bends round in front of the house. It ends at a boundary stone between the parishes of Hornsey and Stoke Newington, marked ‘1700’, although it would originally have turned a right-angle here and flowed back west along the edge of the park. Where there used to be a little iron-railed bridge over the stream is the site of a café where the chips are fantastic and the industrial-strength bright-red ketchup makes your lips sting. This is the very edge of Stoke Newington (origin: ‘New Farm by the Tree Stumps’). The area, once a smart retreat for rich city types and intellectual nonconformists such as Daniel Defoe and Mary Shelley. went downhill badly after the war and by the seventies was regarded as an inner-city shit hole. Over the last ten years or so the urban pioneers (people with snazzy glasses, sharp haircuts and a liking for trendy food) have moved in and the place is on the up once more. I walk down the wide Petherton Road, which has a grassed island in the middle where the river used to run, towards Canonbury.

At Canonbury I enter a little narrow park where an ornamental death mask of the river runs for half a mile. This is a great idea in principle but in reality it’s faux-Zen Japaneseland precious, some sensitive designer’s idea of tranquillity, rather than reflecting the history of the area and its people. Completely covered in bright green algae, the river looks more like a thin strip of lawn. Here, too, the river marks a boundary, between the infamous Marquess estate on one side and Tony Blair Victorian villa land on the other.

Canonbury Park, further south, is a more typical London scene: silver-haired senior citizens in their tight-knit Special Brew Appreciation Societies sit and watch the world go by (and shout at it now and again in foghorn voices). More and more people walk around these days clutching a can of extra strong lager, as a handy filter for the pain of modern urban life. Out of the park and into Essex Road – a statue of Sir Hugh Myddelton stands at the junction of Essex Road and Upper Street on Islington Green.

The walk ends at Clerkenwell at the New River Head, once a large pond and now a garden next to the Metropolitan Water Board’s twenties offices. Above the main door is the seal of the New River Company showing a hand emerging from the clouds, causing it to rain upon early seventeenth-century London. I go into the building and take a photo, then ask the receptionist if there are any pamphlets or information about the New River. He shrugs, although apparently the seventeenth-century wood-panelled boardroom of the New River Company still exists somewhere in the building.

A few days later I mentioned the walk I’d done to my next-door neighbour. She was already beginning to sense that I was obsessive, as it’s all I ever talk about to her these days, and told me about a book that mentions the New River. A family friend had lent it to her years before. Would I like to have a look at it? Ha ha. Give me the book, old woman, I screamed, twitching, and nobody will get hurt. It’s a crumbling old volume on the history of Islington, printed in 1812. Inside is a pull-out map from the 1735 which shows not only the New River but also a ‘Boarded River’ not on any of my other maps. What is this? I re-read the chapter in Wonderful London on the lost rivers and searched the net. Up comes The Lost Rivers of London, by Nicholas Barton. A couple of days later I’m eagerly poring over its contents – a survey and histories of many of the lost rivers – including the map he’s included with the routes of various underground rivers. According to him, it’s not the New River flowing under my road, but something called Hackney Brook. This is confusing.

But then I remembered the can of strong lager in the old pump house. Could it have been a clue to the New River’s mystery, a key to a parallel world? Naturally, I decided that it was – mad pissed people can see the barriers that are hidden from the rest of us, that’s why they stick to the areas they know. Perhaps, if I got pissed on extra strong lager and wandered out into the street I too might see the invisible lines and obstacles opening up before me. I promptly went out and bought a selection of the strong lagers on sale in my local off-licence. Kestrel Super, Carlsberg Special Brew, Tennent’s Super and Skol Super Strength (they’d run out of Red Stripe SuperSlash).

‘Having a party, mate?’ asked the shopkeeper.

When John Lennon first took LSD he apparently did so while listening to a recording of passages from the Tibetan Book of the Dead translated by Timothy Leary, some of which ended up as lyrics in ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, the last track on Revolver. Looking for a more modern psychic map I decided to watch one of my daughter’s videos, The Adventures of Pingu.

Skol Super (‘A smooth tasting very strong lager’ – alc. 9.2% vol.) 7.30p.m.: Tastes salty, tar, roads, burnt treacle. The side of my head starts to pulsate almost straight away. After five or six sips I feel like I’ve had a few puffs of a high-quality spliff; I should stop now. But no, my need for scientific knowledge is too strong. Sounds are much louder. The radiator behind the settee suddenly comes on and I nearly jump out of my skin. I’m becoming superhumanly sensitive already. I feel that my powers are increasing. Like someone out of the X-Men – actually, that’s not a bad idea for a comic book series, a group of superheroes who are all pissheads.

Carlsberg Special Brew (‘Brewed since 1950, Carlsberg Special Brew is the original strong lager. By appointment to the Royal Danish Court’ – Blimey, must be hard work being a royal in Denmark – alc. 9.0% vol.) 9.30p.m.: Took ages to finish the first one. This has a dry-sweet taste and lighter colour with a damp forty-year-old carpet smell. Could possibly do with another couple of years to age properly. It sobers me up after the Skol. Pingu, on its fourth re-run, is getting a little bit boring. Fucking throbbing in my head. This feels like poison in my system.

Tennent’s Super (‘Very strong lager. Consumer Helpline 0345 112244. Calls charged at local rate’ – alc. 9.0% vol.) 10.20p.m.: Sweet, more like normal beer with a nice deep amber colour and a thick frothy head. A few swigs of this and I’m really starting to feel pissed. I can feel large areas of my brain closing down for the night. But which parts, that’s the question?

‘On a scale of 1–100, how much shite am I talking now?’ I ask my wife.

‘Well, it’s difficult to say. You regularly talk a lot of shite.’ (I look hurt.)

‘But, yeah, any more than normal?’

She doesn’t answer. A police car, siren blaring and lights flashing, zooms down our road. I quickly rush upstairs and search for a copy of The Golden Bough. I don’t have one – never have. I’m drunk. I phone the Tennent’s Super Consumer Helpline and leave a message about the dangers of living over groundwater.

Kestrel Super (‘Super strength lager – an award-winning lager of outstanding quality’ – alc. 9.02% vol.) 11.20p.m.: Smells of Belgian beer. Very complex taste, with strong malt notes, flowery like a real ale. I stroke my chin. I want to unbutton my itching head which feels like it’s covered in chicken wire yet strangely I feel very focused. I have also started talking to myself in hyperbabble while thinking I’m actually very nice looking. Actually.

I suddenly realize that we are in deep shit – the evil water spirits are everywhere. Maybe they’re nice, not evil. I think the house might be haunted. I’m doing lots of pissing and have bad gut rot. But I also feel clear headed. Then start to feel a bit sick. I go to the wardrobe, take out a coat hanger, break off the ‘curvy bit’ and snap it in half, bending each piece at right angles. I then get two old pen cases to use as handles and da daaa I have dowsing rods! First off, the sitting room. I wander around and the rods are going crazy – there’s water everywhere. Or is it because I’m a bit pissed or walking over the house’s water pipes? I spend the next hour wandering around our road and the nearby streets, charting the areas above water, and noting down my findings on bits of crumpled-up paper. According to my calculations the river (whichever one) misses our house by about 10 feet and comes up the adjacent road then crosses over and runs under the pavement for a while before going underneath the houses and coming out again at the used car lot next to the White House pub. Back at the other end of the road I check out the Scut Line. It’s the start of a very steep hill heading towards Highbury Village. People who are pissed cant wolk up it gravity take sover superbrew legs. I am startinf to git a hedache or is it my riverline-seeuin 3rd eye? Uuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuhh.

At the end of the month the heavens opened yet again, but this time they didn’t stop. Waterfalls of rain, thunder and lightning, dark grey skies. The local streets once more began to turn into small lakes and streams. Down on Blackstock Road where, according to the old book the Boarded (New) River and Hackney Brook crossed, ponds formed in the road. Around the country people were flooded out of their homes. And the London rivers seemed to be rising too.

The problem with burying rivers is that we can’t see, and know, what they’re doing. In times of heavy rain it’s not that the rivers themselves will burst – they are encased in concrete – but that the small springs and streams that would originally have flowed into them can’t get into the concrete culvert that the river has become and simply follow the old course, spreading out over the river’s flood plain. Four million people in London live on the flood plains of the lost rivers. One night in early November, Church Street was completely flooded at exactly the point where the New River used to cross over and head south towards Canonbury. The next morning, after more rain, there were huge floods in Clissold Park just where the Hackney Brook would have skirted around the ponds. At the end of Grazebrook Road, pockets of people wandered around in wellies, staring with disbelief at the expanding pool. We’ve got so cocooned in our soft, warm modern urban world that we’ve forgotten that nature is just outside the door. Some day these nineteenth-century shelters of bricks and mortar won’t be able to protect us any more.

One morning the tall smart-blazered Jehovah’s Witness appeared again at my front door and begged me to take a copy of the Watchtower.

‘See all this weather. It’s the end times. Just like the Bible says. Read this leaflet. Promise me you’ll read it.’

Film idea: The Hugh Myddleton Story

Adventure. Big budget/People dying. There’s a race on to see who can come up with the best idea. Myddleton wins but others try to sabotage his project. Love interest: she gets pinched by opposition but he wins her back at end. He also foils Gunpowder Plot and saves King. Not entirely accurate historically. Maybe played by Matt Damon. Shakespeare in there too. And the Spanish Armada. Maybe the fleet can only set sail when they’ve all had enough to drink. Triumphant music at end and high fives as Myddleton blows up Spanish ships. English all played by Americans, Spanish all played by posh English.