Читать книгу Frances E. W. Harper - Utz McKnight - Страница 13

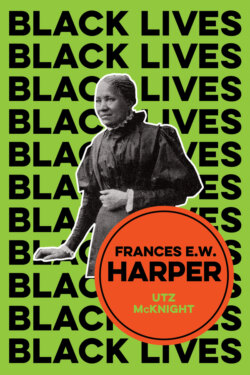

Frances Harper in the 1860s and 1870s

ОглавлениеFrances Harper married Fenton Harper in 1860, just as the Civil War broke out. The two of them and his three children moved to Ohio, bought land with the money that she had made from the sale of her poetry, and started a dairy farm. While taking a break from the speaker circuit, Frances Watkins Harper remained active as both a lecturer and an essayist during these years (Foster, 1990, p. 18; Still, 1872, pp. 764–6). In 1864, Fenton Harper died, leaving Frances Harper with four children to support and considerable financial debt. Since, as a woman, she was unable to secure the debt, after the bank repossessed her dairy equipment she was forced to lecture to generate income beyond the royalties from her books. It is not evident from biographical material what she arranged for the older children, but it is known that Frances Harper moved to Boston with her biological child, Mary, after she lost the farm.

Shortly after the end of the Civil War, in 1865, Frances Harper began her travels in the South, becoming one of many Northerners who sought to assist the newly freed slaves (Dudden, 2011, p. 115). She lectured and taught throughout the Southern states, often to audiences made up exclusively of Black women, but also to racially mixed audiences comprised of men and women, sometimes staying in the cabins of former slaves (Still, 1872, p. 772). Based upon these experiences, Frances Harper found it imperative to write about the difficult and impoverished circumstances of the newly freed people in her poetry and fiction.

Harper also participated in the new national organizational efforts by which activists in the North sought to secure political rights for the newly freed persons. That this effort was, by participants, increasingly connected organizationally with the rights of women is not a coincidence, as the issue of rights was one around which women had agitated since the founding of the nation (Brooks, 2018, p. 300). The success of this national organizational activity in the decades before the War was evident in the Women’s Rights Convention in 1848 in Seneca Falls. The Civil War represented for the government an implosion of institutional norms, which brought with it a renewed organizational effort to secure rights for women.

In 1866, Frances Harper gave a speech at the Eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention in New York. This speech represented her coming into national prominence for the post-War activist push for women’s rights, work that would occupy her for the major part of the next few decades. For Harper, this transition from Abolition to Women’s Rights after the War seems straightforward, given her personal and professional interests, and the relationships she had made through the success of her public speaking and published writing. She had always been a public advocate for political equality as a free Black woman, and the rights of women and free Black people were the major topic of the post-War period. She was also one of the most prominent public figures in the Abolitionist Movement, a nationally recognized poet and public speaker whose work was often in print in the newspapers and magazines of the Black community.

As she observes in her speech in 1866, “We Are All Bound Up Together,” race after the Civil War remained a central concern for her vision of the country. In the speech, she describes how her friend Harriet Tubman, the last time she saw her, had swollen hands from having to fight a train conductor who had tried to eject her from the train. Calling Tubman “Moses,” Frances Harper says, “The woman whose courage and bravery won a recognition from our army and from every black man in the land, is excluded from every thoroughfare of travel” (Harper, 1990f, p. 219). She goes on to ask whether White women need the vote to get them to care about the injustices done in their name (Dudden, 2011, pp. 84–5; Painter, 1996). This direct convergence of the issues of gender and race in the speech reveal how, for Harper, the idea of Black men supporting Tubman in her efforts to bring slaves to freedom could potentially lead to their improved understanding of the need to now support the rights of women. The importuning of Tubman as a woman in a physical altercation with the conductor should allow for the understanding by White women of the need for rights for Black people, as in their own struggle. Was not Tubman also a woman, yet having to physically fight to be allowed on a train as a Black person?

The provision by Frances Harper already in 1866, in a major public speech, of a vision of intersectional political responsibility is remarkable and singular. She clearly represented for attendees these very ideas of a conjoined, collective argument for rights for Black people and women in her own person, and was aware of the discursive arguments required to bring this political awareness to her audience. Invoking Harriet Tubman as a figurative Moses for the nation in her speech merged the two competing ideas of freedom and slavery in the form of a Black woman working on behalf of an idea of rights for everyone in the nation. Very shortly after this speech, the idea of a unity of purpose between White women and Black people would collapse in the face of the development of the Black codes and Jim Crow. With this went also the acceptance of a more capacious vision of racial and gender equality, for which Frances Harper was the foremost advocate in print in the decades after the War.

In 1869, Frances Harper published the book of poems Moses: A Story of the Nile, and she serialized her first novel, Minnie’s Sacrifice, in the Christian Recorder. She had been traveling across the Northeast and in the South, teaching and lecturing in the years since the end of the War, and her health was failing because of the rigors of the schedule she set herself (Still, 1872). It must have been a very physically demanding and precarious social experience to travel in the war-torn South at the time. Both published works engage directly with the theme of how to develop gender and racial equality in the society, and reflect Harper’s commitment to the idea of rights and obligations for Black people in this new society.

As a consequence, in part, of this physical debilitation, in 1871, at the age of 46, Frances Harper was back in Philadelphia, where she settled, buying a house for herself and Mary. There she worked as Assistant Superintendent of the YMCA, and continued to write essays, fiction, and poetry. At this time, she also began working for the Temperance Movement.

Like many of her contemporary poets, Harper reissued published works with amendments and new material. In her lifetime, there were at least 20 editions of Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects, and 10 other extant volumes of poetry, her 4 novels, numerous essays, speeches, and letters were published. Harper was a poet and writer who, at 46, had already accomplished as much as most in their entire careers. She was a public figure, someone who was immersed in the work of national organizations.

Frances Harper belonged to a small set of women who regularly wrote and spoke in public, but was the only Black woman among them to brave the public organizational arena in addition to writing. Because Harper was an activist writer and poet, much of her written work involved experiences that occurred as a result of those movements and organizations of which she was a part. For her, the concerns of her art always existed alongside her concern for the place of the writer and poet in defining the political ideas that determine how people should live together.

In 1871, Harper published Poems, and then, in 1872, she published what many consider her most important volume of poetry, Sketches of Southern Life (Fisher, 2008, p. 57; Graham, 1988, p. xliv). Taken together, Moses and Sketches represent an important contribution to the African American poetry canon, a detailed and excellent analysis of which was produced by Melba Joyce Boyd (1994) in her book Discarded Legacies (Graham, 1988, p. xli). Frances Harper continued to publish poetry in the decades that followed, particularly – but not exclusively – addressing the themes of individual morality, gender, race, and temperance. She wrote the newspaper column “Fancy Sketches” from 1873 to 1874, which could be considered a short second novel, and serialized the novel Sowing and Reaping in the Christian Recorder from 1876 to 1877.

The gaps between the novels are filled with organizational activity, essays, and speeches, but the work that Frances Harper was engaged in after the Civil War was largely obscured by the social transformation wrought by the reconsolidation of White authority and new laws requiring Black subordination. The concepts of political rights and equality for Black people that Frances Harper had championed for two decades before the War had, by the 1870s, proven ephemeral and elusive. Her writing and poems represented a literary call to a collective counter-authority to resist the rise of a new restrictive White South after the War, which was taken up in the 1890s by a new generation of Black writers and poets who could depend on the publishing traditions and literary networks that she and others had developed in the decades after the War (Gordon, 1997, p. 54).

After 1871, Frances Harper’s activism was defined by combining the disparate strands of African American educational and social development, the Suffragist Movement, and the Temperance Movement into a theme of racial uplift for Black people (Terborg-Penn, 1998, p. 67). This was a more complicated field to survey for her and her audience than Abolitionism, and while her popularity never waned during her lifetime, the biographer William Still stopped his discussion of her life after the early 1870s.

In this period, Harper authored 3 novels, at least 40 poems, and numerous essays and letters. But she was also central to the development of the Temperance and Suffrage movements, participating in local, state, and national organizational efforts. In 1872, it would still be 20 years before Iola Leroy was published, which was one of the most popular novels of the latter part of the nineteenth century. What occurred during that time to dampen our interest today in that period of her life?

The 1870s and 1880s, like the more recent 1980s and 1990s, were periods of political reconsolidation and conflict, after major shifts in the social institutions that described racial difference. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, in a similar way to the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Acts of 1965, transformed how people could bring their interest in racial inequality to bear on their social activity. Prohibiting slavery, making all Black people citizens, and granting all men 21 years and older the right to vote transformed the organizations that had formed around these issues before and during the Civil War (Dudden, 2011, pp. 162–3).

It seems too easy to make the stark claim that Black men did not fulfill their promise to Black women when, after being granted the vote, they refused to advocate vociferously for the rights of women. And yet, when we read Frances Harper’s novels and poetry of the period after 1869, there is a missing element throughout – the widespread organization of Black men on behalf of women’s rights. Even though many Black men, such as Frederick Douglass, did argue in conferences and in meetings about the importance of Black women to their cause of democracy in the society, the failure of the immediate post-War movement to secure the voting rights of Black women has to be seen as an intersectional compromise of race and gender, damaging to the effective development of the rights of the Black community in the decades that followed (Terborg-Penn, 1998, pp. 62, 81).

However, the truth is more complicated than a description of the capacity of a unidimensional gender politics to divide the nascent and fragile commitment to a collective Black community politics by Black men and women after the War. In fact, the major political contestation that occurred publicly within the national organizations was that between White and Black women, and the capacity of racial politics to split the women’s Temperance and Suffragist national organizational effort along racial lines (Foster, 1990; McDaneld, 2015, pp. 395–402; Painter, 1996; Parker, 2010, pp. 129–36; Rosenthal, 1997, p. 159). The institutional expansion of a Whiteness that, after the War, would realize new possibilities for social advancement was too effective a political force and overcame the desires of both White and Black women to remain in coalition on the issue of racial equality. This wasn’t the case of interpersonal politics overwhelming an opportunity, even though this is the focus of much research by historians – but a problem of how racial difference is reproduced within institutions.

As social imperative, through violence, and then as a political reality, the collapse of the institutions that supported the enslavement of African Americans required new institutional structures and processes. The auction system, the slave catchers, the transportation of slaves to market, the banking and loan system, insurance agents, the plantation owners, and small farms that owned one or two slaves, along with slave labor that engaged in everything from farm work, household cleaning, nursing children, artisanship, to prostitution on behalf of their owners, were replaced in the years immediately after the War with a new description of racial inequality. While the women’s rights national organizations, as well as the activists within the Abolitionist Movement, were important to this development, the defining elements were a series of decisions made by the US government after 1865. Rather than ascribe racial politics to a deterministic process, one in which a particular event or material condition is primarily responsible for the perpetuation of racial inequality, it is better to be more realistic and think of the many different things that would have contributed to the rise of a new Southern White authority after the War.

Already at the War’s end, Black codes were used to maintain the legal subordination of Black people in the South, and the organization of the Ku Klux Klan and other militia groups threatened violence toward anyone with public aspirations toward more equal social relationships. Lynching began to occur as an institutional outgrowth of these processes of consolidating Whiteness around violent suppression of the idea of equality. The Freedmen’s Bureau and Union Army were also important factors in this description of what was possible. But, also, Black people migrated west and north, and had fought and provided care for the Union Army, promoting in their activism the potential for a longer journey to live elsewhere in the country. The effects of the War on the population and the land were obvious. Millions can’t be killed, slave labor replaced wholesale with wage labor, and the countryside burned, without there being difficulties with maintaining economic processes that could sustain stable living conditions for most in the South. The North was also deeply affected.

In this context, how effective would local initiatives have been, if they had existed, in addressing the idea of racial social equality after the War? How effective are the ideas of implicit bias and diversity training today, without a better understanding than we have of how race difference is described within institutions, in our lives? This is not to ignore the political and social consequences of the failure in the period after the War to unite White and Black women in the cause of racial equality, but it would be almost 60 years after the War when White women could first vote in large numbers in the US, and almost a century after the War before Black women could similarly vote.

It was not a failure of will or factionalism between women and Black people that resulted in these partial and imperfect democratic political processes in the US after the Civil War. We shouldn’t blame the victims of the processes of racial and gender inequality for inaction and ineffectiveness, but instead look to the problem of the successful reconsolidation of authority in supporting the ideas of racial and gender hierarchy. By the 1880s, the possibility of Black men voting was likewise fading in practice, as a racial and gendered politics of inequality became a description of social relations throughout the South and North.