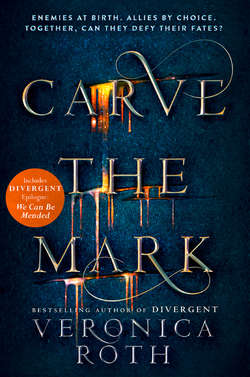

Читать книгу Carve the Mark - Вероника Рот, Veronica Roth - Страница 15

Оглавление

A SEASON LATER, WHEN I was eight, my brother barged into my bedroom, breathless and soaked through with rain. I had just finished setting up the last of my figurines on the carpet in front of my bed. They were scavenged from the sojourn to Othyr the year before, where they had a fondness for small, useless objects. He knocked some of them over when he marched across the room. I cried out in protest—he had ruined the army formation.

“Cyra,” he said, crouching beside me. He was eighteen seasons old, his arms and legs too long, with spots on his forehead, but terror made him look younger. I put my hand on his shoulder.

“What is it?” I asked, squeezing.

“Has Father ever brought you somewhere just to … show you something?”

“No.” Lazmet Noavek never took me anywhere; he barely looked at me when we were in the same room together. It didn’t bother me. Even then, I knew that being the target of Father’s gaze was not a good thing. “Never.”

“That’s not exactly fair, is it?” Ryz said eagerly. “You and I are both his children, we ought to be treated the same. Don’t you think?”

“I … I suppose,” I said. “Ryz, what is—”

But Ryz just placed his palm on my cheek.

My bedroom, with its rich blue curtains and dark wood paneling, disappeared.

“Today, Ryzek,” my father’s voice said, “you will give the order.”

I was in a small dark room, with stone walls and a huge window in front of me. My father stood at my left shoulder, but he seemed smaller than he usually was—I only came up to his chest in reality, but in that room I stared right at his face. My hands were clenched in front of me. My fingers were long and thin.

“You want …” My breaths came shallow and fast. “You want me to …”

“Get yourself together,” my father growled, grabbing the front of my armor and jerking me toward the window.

Through it I saw an older man, creased and gray haired. He was gaunt and dead in the eyes, with his hands cuffed together. At Father’s nod, the guards in the next room approached the prisoner. One of them held his shoulders to keep him still, and the other wrapped a cord around his throat, knotting it tightly at the back of his head. The prisoner didn’t put up any protest; his limbs seemed heavier than they were supposed to be, like he had lead for blood.

I shuddered, and kept shuddering.

“This man is a traitor,” my father said. “He conspires against our family. He spreads lies about us stealing foreign aid from the hungry and the sick of Shotet. People who speak ill of our family can’t simply be killed—they have to be killed slowly. And you have to be ready to order it. You must even be ready to do it yourself, though that lesson will come later.”

Dread coiled in my stomach like a worm.

My father made a frustrated noise in the back of his throat, and shoved something into my hand. It was a vial sealed with wax.

“If you can’t calm yourself down, this will do it for you,” he said. “But one way or another, you will do as I say.”

I fumbled for the edge of the wax, peeled it off, and poured the vial’s contents into my mouth. The calming tonic burned my throat, but it took only moments for my heartbeat to slow and the edges of my panic to soften.

I nodded to my father, who flipped the switch for the amplifiers in the next room. It took me a moment to find the words in the haze that had filled my mind.

“Execute him,” I said, in an unfamiliar voice.

One of the guards stepped back and pulled on the end of the cord, which ran through a metal loop in the ceiling like a thread through the eye of a needle. He pulled until the prisoner’s toes just barely brushed the floor. I watched as the man’s face turned red, then purple. He thrashed. I wanted to look away, but I couldn’t.

“Not everything that is effective must be done in public,” Father said casually as he flipped the switch to turn the amplifiers off again. “The guards will whisper of what you are willing to do to those who speak out against you, and the ones they whisper to will whisper also, and then your strength and power will be known all throughout Shotet.”

A scream was building inside me, and I held it in my throat like a piece of food that was too big to swallow.

The small dark room faded.

I stood on a bright street teeming with people. I was at my mother’s hip, my arm wrapped around her leg. Dust rose into the air around us—in the capital city of the nation-planet Zold, the dully named Zoldia City, which we had visited on my first sojourn, everything was coated in a fine layer of gray dust at that time of year. It came not from rock or earth, as I had assumed, but from a vast field of flowers that grew east of here and disintegrated in the strong seasonal wind.

I knew this place, this moment. It was one of my favorite memories of my mother and me.

My mother bent her head to the man who had met her in the street, her hand skimming my hair.

“Thank you, Your Grace, for hosting our scavenge so graciously,” my mother said to him. “I will do my best to ensure that we take only what you no longer need.”

“I would appreciate that. There were reports during the last scavenge of Shotet soldiers looting. Hospitals, no less,” the man responded gruffly. His skin was bright with the dust, and almost seemed to sparkle in the sunlight. I stared up at him with wonder. He wore a long gray robe, almost like he wanted to resemble a statue.

“The conduct of those soldiers was appalling, and punished severely,” my mother said firmly. She turned to me. “Cyra, my dear, this is the leader of the capital city of Zold. Your Grace, this is my daughter, Cyra.”

“I like your dust,” I said. “Does it get in your eyes?”

The man seemed to soften a little as he replied, “Constantly. When we are not hosting visitors, we wear goggles.”

He took a pair from his pocket and offered them to me. They were big, with pale green glass for lenses. I tried them on, and they dropped straight from my face to my neck, so I had to hold them up with one hand. My mother laughed—light, easy—and the man joined in.

“We will do our best to honor your tradition,” the man said to my mother. “Though I confess we do not understand it.”

“Well, we seek renewal above all else,” she said. “And we find what is to be made new in what has been discarded. Nothing worthwhile should ever be wasted. Surely we can agree on that.”

And then her words were playing backward, and the goggles were lifting up to my eyes, then over my head, and into the man’s hand again. It was my first scavenge, and it was unwinding, unraveling in my mind. After the memory played backward, it was gone.

I was back in my bedroom, with the figurines surrounding me, and I knew that I had had a first sojourn, and that we had met the leader of Zoldia City, but I could no longer bring the images to mind. In their place was the prisoner with the cord around his throat, and Father’s low tones in my ear.

Ryz had traded one of his memories for one of mine.

I had seen him do it before, once to Vas, his friend and steward, and once to my mother. Each time he had come back from a meeting with my father looking like he had been shredded to pieces. Then he had put a hand on his oldest friend, or on our mother, and a moment later, he had straightened, dry-eyed, looking stronger than before. And they had looked … emptier, somehow. Like they had lost something.

“Cyra,” Ryz said. Tears stained his cheeks. “It’s only fair. It’s only fair that we should share this burden.”

He reached for me again. Something deep inside me burned. As his hand found my cheek, dark, inky veins spread beneath my skin like many-legged insects, like webs of shadow. They moved, crawling up my arms, bringing heat to my face. And pain.

I screamed, louder than I had ever screamed in my life, and Ryz’s voice joined mine, almost in harmony. The dark veins had brought pain; the darkness was pain, and I was made of it, I was pain itself.

He yanked his hand away, but the skin-shadows and the agony stayed, my currentgift beckoned forward too soon.

My mother ran into the room, her shirt only half buttoned, her face dripping from washing without drying. She saw the black stains on my skin and ran to me, setting her hands on my arms for just a moment before yanking them back, flinching. She had felt the pain, too. I screamed again, and clawed at the black webs with my fingernails.

My mother had to drug me to calm me down.

Never one to bear pain well, Ryz didn’t lay a hand on me again, not if he could help it. And neither did anyone else.