Читать книгу Mystery in Moon Lane - A. A. Glynn - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

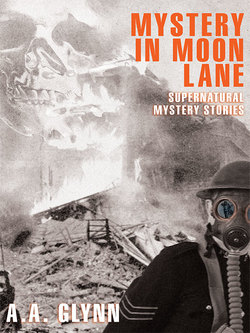

ОглавлениеMYSTERY IN MOON LANE

Manuscript found in the papers of Septimus Dacers, sometime detective in a private capacity. Mr Dacers was born in London in 1825 and died in that city in 1908, aged 83.

That evening and my unusual visitor have remained vivid in my memory down all the years and, through all the decades since, I have puzzled over the strange affair that followed his arrival at my apartments.

I was idle and worried in spite of the pleasant warmth of a late spring evening. The London authorities were worried, too, for the first cases of cholera had emerged among the ragged inhabitants of the wretched rookeries of the St. Giles region. It had not reached the dangerous proportions as it had among our unfortunate troops in the Crimea, but it was likely to increase with the summer. My own trouble was money—or rather the lack of it. I needed a client, a commission to bring me out of idleness, because I needed three weeks’ back rent to take the angry glare from the eyes of my landlady, Mrs. Slingsby. That glare threatened eviction.

Sitting by the open window, gazing gloomily into the street, I was disturbed by a sharp tap at my door, Mrs. Slingsby’s unmistakable calling card.

With a sinking heart, I opened the door and my landlady was indeed there. But she was not alone for, behind her stood a tall, gaunt man. Despite the warm evening, he was peculiarly muffled in a heavy black surcoat and with a scarf wrapped around the lower half of his face, so that only a pair of glittering eyes showed between it and the brim of his tall hat.

“A gentleman to see you, Mr. Dacers,” said Mrs. Slingsby in an acid voice, which plainly had an undertone of: “And you still owe three weeks’ rent!”

I thanked her, ushered in the visitor, and hastily closed the door on the lady and her glare.

“You are a detective, Mr. Dacers?” the man spoke through his scarf. His accent was heavy and foreign.

I assured him that I was, and waved him towards the better of my two shabby chairs.

“But you are not associated with the police?” he asked, seating himself.

“No, I act in a private capacity, but I have helped the police on occasion. I must warn you, though, that I never undertake anything contrary to criminal law,” I told him.

“I do not propose any illegal ventures,” said my visitor, revealing that despite his heavy accent, his command of English was good. “But I do not want it known that I am here in London. I have come from France where I am known among the scientific community, and there are those both here and in my home country who keenly seek intelligence of certain projects on which I am engaged.”

He began to unwind his concealing muffler, revealing a dark, sharply intelligent face with moustachios and beard of the fashion called an ‘imperial’.

“My name is Duclois—Auguste Duclois. You might have heard of me,” he declared somewhat in the manner of a grand actor.

“Duclois, of the electrical impulses!” I answered. “Yes, of course I’ve heard of you. Your name was in the papers not six months ago.”

He gave a snort. “The papers ridiculed me, M’sieu Dacers. They sneered at my experiments aimed at changing human behavior by electrical impulses. And all of them, in England, on the Continent, and in America, had everything wrong, as usual. They didn’t understand the half of my reasoning. Damned, ignorant scribblers, all of them!”

“I’ve little knowledge of scientific matters,” I said, noting that, with his erratic gestures of the arms and his rapid speech, my visitor was mounting what was obviously a hobbyhorse. Impatiently I waited for him to get to the point of his visit.

“Ah, in that you are like most men, my dear sir,” replied Duclois. “You can’t see an obvious fact when it is staring you in the face. It is given to genuine seers, such as myself, to grasp the potential of anything new on the scientific horizon. I haven’t yet fully explored the possibilities of electricity, but I know the wonders it can unfold, the untold benefits it can eventually bring to mankind. You might think we have reached the ultimate in progress now that we’re in the great age of steam; that we have all but conquered the world with the huge engines seen so recently, grinding and clanking at your Great Exhibition of 1851—but no! No, Mr. Dacers! There are more achievements to be aimed at. Consider the part the electric telegraph played in capturing that murderous couple, the Mannings, here in England only three or four years ago. But developments infinitely greater than the mere telegraph are waiting once we fully harness the mysteries of electricity. I am one of the select few who are engaged in that pursuit, sir, persevering despite the ridicule.”

“Would you care for a glass of sherry?” I ventured, hoping he would refuse, for my solitary bottle was all but down to the dregs.

“Thank you, no. I would prefer to get down to business. I am willing to hand over a ten-guinea retainer here and now, and a further ten on completion of a certain task.”

My heart lifted. The initial ten guineas alone would settle my rent bill and considerably replenish my supply of sherry, and twenty guineas all told for a single assignment was quite unprecedented.

I strove to put on the demeanor of a dignified man of business and said, soberly: “As I am not at present engaged, sir, I can act on your behalf.”

“Très bon!” he responded with a rare lapse into his native tongue. “It is largely a matter of, as you might say here, keeping an eye on a certain person. I saw a newspaper report of your doing something singular in the recent railway fraud case in which the Metropolitan Police enlisted your help. That is why I sought you out.”

I shuddered, recalling the railway fraud case and the miserable winter hours I had spent watching certain premises and noting the comings and goings of various high-placed individuals and observing the companions they consorted with. Then the prospect of a twenty-guinea fee brightened my mood again.

“I am on the brink of quite startling discoveries, notwithstanding the barbs of the scoffers,” continued Duclois. “Not least among those scoffers is a great rival of mine, one who shuns the limelight so that few among his countrymen here in England even know his name. He is a man of ability for all his scoffing at fellow researchers and for all his deliberate choice of obscurity. I believe he is researching into the very revolutionary applications of electricity, as I am myself. I want to know what he is up to, and I have a particular desire to know what equipment he is building and using.”

“But I’m no specialist in matters scientific,” I pointed out.

“It will be chiefly a matter of observation on your part, Mr. Dacers—well within your powers,” said Duclois. “My wretched rival Amos Chaffin; this snake in the grass, as you English say, has dogged me for years with his ridicule. He tried to make me a laughing stock at the Berlin Congress of Science in 1850, then went to ground here in London, going into obscurity to work on a scheme, the very basis of which I know he stole from me. He doesn’t know that I have followed him, and am aware of where he is lurking. I must know more, however, but dare not show myself to him.”

“Where might he be found?” I asked.

“Not far from here. He has established a workshop in a portion of an old warehouse in Moon Lane where he is working alone. Do you know Moon Lane?”

I nodded, flinching inwardly. It was dangerously close to the sprawling St. Giles slum, known to the criminal classes as ‘The Holy Land’. Gangs of thieves and violent malefactors of every stripe inhabited it, clustering together in gangs to resist the forces of the law. Whenever the Peelers ventured there, they went in squads, often armed with cutlasses and sometimes pistols. However, the hefty fee promised by Monsieur Duclois was a powerful inducement.

“How will I know him?”

“Easily—a short, squat fellow, sharp-nosed and pockmarked. Oh, and he has a ridiculous set of false teeth which always seem to be in danger off falling out.”

“And what must I particularly note about Mr. Chaffin’s activities?” I enquired.

“Particularly what materials are delivered to his place of experiment and in what quantity,” Duclois said. “There will doubtless be carboys of acid and jars of distilled water and, very likely, sheets of slate. The scale of such deliveries will give me some idea of the scale of his experiments.”

“Merely that?” I asked.

“Not entirely. I suppose it will not be beyond your wit to enter his workshop, and I greatly desire a sketch of what he is building there—the roughest sketch will do so long as you can indicate the size of whatever he has set up. Have you ever seen an electrical battery?”

“Yes, at the Great Exhibition in ’51.”

“Well, I expect you’ll see something of the kind at Chaffin’s lair, but probably on a very large scale, but I want to be sure. I must steal a march on the rogue—to pay him out for filching the foundations of my own plans, as I know he has. I want to forestall him in giving the world one of the most astonishing achievements known to science and to trounce him once and for all.” Duclois was gesticulating again. And his eyes were glittering with near fanaticism.

“You have three days, Mr. Dacers. I shall be back then to discover your results. I shall not tell you where I am staying, for it is essential that I remain as scarce as Chaffin himself while I’m in London.”

He fished inside his surcoat and produced a large purse from which he took a handful of gold sovereigns and silver. He counted out ten guineas and placed the money in my hand. “And the rest on successful completion of the matter,” he said.

* * * *

At once, I settled my back rent, which considerably sweetened Mrs. Slingsby’s disposition and removed the threat of the debtors’ prison. Next morning, I set about my commission, choosing the right moment to leave the house. It being Tuesday, Mrs. Slingsby sent her girl slavey out to the market as usual, then departed on her regular weekly visit to her sister, so I was alone in the house. I put on rough boots, moleskin trousers, a coarse jacket, and a stove-in hat such as a workingman might wear, a costume suited to an excursion in the region of The Holy Land. I applied a scrubby set of whiskers and false moustaches, put a small notebook and a blacklead pencil into my pocket, and went forth. I left the house by the rear door and, after walking the back lanes of several streets, I emerged in the region of Oxford Street.

The air was balmy and the odors of the streets were only too evident. In the better-class thoroughfares, workmen were spreading quicklime in the gutters, following the usual precaution in the cholera season. I walked along Oxford Street, heading for the vicinity of St. Giles, trying to think up some stratagem for entering the Moon Lane warehouse.

Midway along Oxford Street, I passed a workman, shoveling quicklime and hoarsely croaking a song that was all the rage that year of 1855:

“Not long ago, in Vestminster,

There lived a ratcatcher’s daughter;

But she din’t quite live in Vestminster,

For she lived t’other side of the vater.…”

Ratcatcher! I thought to myself, Now, that’s the kind of man who might find employment in the region of Moon Lane. I also took note of the raffish singer’s Cockney idiom as a pointer to character.

Moon Lane was every bit as unprepossessing as it ever was. It was a narrow, snaking crack between old, gray, frowning warehouse buildings, most of which seemed to be empty. Its slimy cobbles were broken and there was a liberal scattering of puddles of filth underfoot. No human life was in evidence at first. Then, just as I entered the lane, a heavy cart drawn by two horses trundled out of a yard set to one side of one of the buildings. The driver was a surly-looking fellow, smoking a clay pipe and with a dirty sack as a cloak. I had to squeeze hard against a cracked wall to allow the animals and the vehicle to pass me. The carter considered me with a beery eye.

“Vot cheer, mate?” he growled as he passed, which encouraged me to believe my disguise was convincing.

“Vot cheer?” I replied. “Votcher been deliverin’—best ale and porter?”

“My eye! Nuffin’ so bloomin’ prime as that, vorse luck,” he called over his shoulder. “Four carboys of bloomin’ acid. Fine bloomin’ boozin’ that’d make!”

As the cart rumbled past, I took note of the legend on its side: ‘Alfred Musprat and Sons, Suppliers of chemicals and acids, Cheapside.’

Four carboys of acid. This was a good start, and this yard was obviously attached to the building, which Amos Chaffin had made his base of operations. I stood at the gate of the yard and surveyed it. Like everything about Moon Lane, it was gloomy and mean. Surrounded on three sides by the flaking walls of neighboring warehouses, it was cluttered with rubbish. The doors of the surrounding buildings were closed and some were boarded up. One, however, stood open, the only sign of there being any kind of activity in the place. I could see four carboys lined up just inside the doorway

I ventured into the yard and looked about cautiously. It was quiet with no sign of life. Cautiously, I walked towards the open door and entered a damp and musty windowless corridor shrouded in gloom. Again, there was no sign of anyone, but the carboys of acid deposited on the threshold suggested that there might be some form of occupancy.

To one side of the corridor, there was another open door and I entered it. I was in a large room where, against one wall, stood four square glass containers, taller than myself, and each filled with a liquid. Within them, I also saw what looked like slabs of slate. I recalled what Auguste Duclois had said about electric batteries, and saw that they did resembled those seen at the Great Exhibition but built on a far bigger scale. There was also a large board with a tangle of wires on it, as well as a metal lever on something of the pattern of those in railway signal boxes.

So far, everything had gone swimmingly. I had not encountered any obstruction and I could begin sketching what I had discovered. Producing my notebook and blacklead pencil, I drew to the best of my ability the set of large containers, the board, and the lever.

Then I heard a footfall in a far corner of the gloomy room, looked towards it and quickly whipped my notebook behind my back as I saw a man of short stature emerging from a door, which the shadows had all but hidden.

“Who the devil are you? What are you doing here?” he bellowed as he advanced on me. He had on a slop coat such as those worn by all manner of workers to protect their everyday street clothes, and a tall hat. True to the description of Duclois, his nose was sharp and his face crabbed and angry.

“Who are you, damn you?” he demanded again and he a quickly put a hand to his mouth, obviously to secure dentures which his angry spluttering seemed to have shaken loose.

I kept my notebook behind my back and began to brazen it out. “Rats, sir. I’m on the look out for rats,” I said.

“Rats? I have not sought the services of a ratcatcher,” bellowed the man who was very clearly Amos Chaffin. “You’re trespassing! Who are you?”

“Smith, sir—Jem Smith. I’m just doin’ my job as instructed by my guv’nor,” I lied, turning on my Cockney persona.

Chaffin squinted at me with an eye matching that of Auguste Duclois for fanatical glitter. “Governor? Who’s your governor?”

“Mr. George Nobbs, practical ratcatcher, from over Seven Dials vay. It vos the cove owning that warehouse over yonder,” I waved vaguely towards the yard beyond the building, “vot asked him to look into the matter of rats seen on his premises. ‘Go and look over the job, Jem,’ says Mr. Nobbs, as he often does. Having some notion of how many rats and where they’re nesting helps us sort out vot we needs in the vay of traps and poisons, d’you see, sir. Have you seen any rats about?”

“Of course I have,” sputtered Amos Chaffin, adjusting his false teeth again. “Rats are always everywhere in London. And I put up with them without the services of ratcatchers.”

“You’ll pardon me, sir, but that’s a mistake,” I said. “There’s talk that the cholera is spread by rats. They’re highly dangerous, sir.”

“Indeed!” growled Chaffin. “I heard there’s a theory that it’s spread by bad water.”

“All wrong, sir. It’s rats vot spread it. You have to root ’em out. Have to find their nests and destroy ’em. I couldn’t help noticin’ that there’s perfect nestin’ conditions behind all that odd stuff you have up against that vall.” I indicated the equipment associated with his experimenting.

His eyes flashed and his teeth threatened to jump out of his mouth of their own volition. “Odd stuff!” he howled. “Do you know what that equipment is? Do you know what you’re in the presence of—what epoch-making scientific advances are in the making in this very room, Smith?”

I shrugged and answered: “I’m sure I dunno, sir. I ain’t had the schoolin’ to understand science. I reckon most of it is gammon.”

“Gammon! You call scientific investigation gammon?” he exploded. “Why, man, here in this very place, miracles are about to be performed upon any objects or persons placed within the electrical field of my machine. Only this morning I concluded calculations which will have far-reaching results—results hitherto undreamed of, even by a fool of a Frog named Duclois who is the bane of my existence.”

I was beginning to think that both Duclois and Chaffin must be totally mad.

It was at this point, with Chaffin in such close proximity to me, that I dropped the notebook that I had been concealing behind my back all the time. Sod’s law decreed that it landed on the grimy floor wide open, with my rough sketches fully visible and Chaffin saw them.

He gave a howl. “Sketches, by God! You’ve been sketching my equipment! You’re no ratcatcher—you’re a damnable spy! You’re employed by Duclois, I’ll warrant!” He made a dive for the book, but I, being younger and more agile, reached it first. As I stowed it in my pocket, he grappled with me, clutching the lapels of my jacket.

“Give me that book, you scoundrel!” he snarled.

Locked together, we reeled across the room, grunting and clawing at each other. Then, near the glass containers and the lever, we fell over and smote the lever with the combined weight of our two bodies. It creaked over from the upright position as the two of us went sprawling, still struggling. It seemed to me that we fell into something like a tunnel, to the accompaniment of a thundering and rushing confusion of sound, and I was dimly aware that Chaffin was there with me, going through the same experience. Then came an abrupt stop to the falling, and I was lying on the ground in what I believed was the same warehouse building.

It was dark and, somewhere in the darkness, I heard the voice of Amos Chaffin shout something incomprehensible that was at once drowned out by more noise—such noise as I never before heard. It was a crashing and banging and thundering of loud explosions and a constant, thrumming droning sound. Then the whole warehouse shook under a dull, shuddering reverberation and there was suddenly light behind us, the blazing yellow and crimson flickering of flames. It briefly illumined the grotesque form of Chaffin in his slop coat and tall hat, running away from where I lay—presumably to escape the flames that were threatening us.

He had barely covered a few yards when a rafter came crashing down on him from the roof. I somehow got to my feet and, in a chaotic welter of swirling smoke and dust, tried to stagger towards where I last saw Chaffin, hoping to help him. I made hardly any progress because I could only blunder around, coughing and half blinded in the confusion.

Then dimly, in this hellish nightmare, I heard a man’s urgent voice shouting something like: “Here—Harry, Nobby, Jack—get the hoses over on this side—there seems to be a bloke trapped under a rafter…quick about it…alert the Rescue.…” Before I realized it, I had somehow wandered free of the building, which was no longer a building but a tumbled mass of bricks, just visible through a swirl of smoke and flames.

Holding my hands against my ears and trying to clear my throat of smoke and dust, I staggered across broken cobbles and shattered bricks, found the doorway of a building and plunged into it, seeking cover and trying to recover my breath. Out of the confusion came a man in a strange costume, though I recognized his greatcoat as something like a Peeler’s. He had an odd helmet like an upturned pudding basin and made of metal. Sure enough, though, the word Police was painted on it in white capitals. His face was smudged with black marks and, like myself, he was choking in the smoke. Coughing, he joined me, leaning against the closed door.

“Hello, mate. You all right?” he shouted over the din when he found his breath. He looked at me enquiringly in the dancing light of the flames, and grinned.

“Cor! Where’ve you come from in that get-up—out of a pantomime? That battered old topper of yours is no protection in this lot. You want to watch out for your head, and there’s a cut on your face. There’s a first-aid post a bit down the lane. Go and ask ’em to clean it up for you.”

He slipped away into the smoky, blazing chaos, leaving me more bewildered than before.

Now that my head had cleared, I remembered Amos Chaffin, trapped under a rafter in the warehouse. I had to get back to him—had to help him out. I was beginning to see that our predicament had something to do with his electrical equipment, which our grappling must have accidentally activated. I recalled what Chaffin had said—something about objects or people being affected by the electrical field of his machine.

Though I was no scientist, it seemed to me that if I was to get back to where I belonged, I had to be within the influence of that field, which lay somewhere within the warehouse.

Crouching into the smoke and flames, I scrambled over humps of rubble towards the wreckage of the warehouse on which the men in the strange costumes and metal helmets were playing jets of water onto the flames. I got within a section of shattered wall and blundered onward until I believed I was somewhere near where I last saw Chaffin. Then I heard a hoarse voice, yelling above the explosive cacophony: “Hey, come back! You can’t go in there! What’re you up to—looting? Come back, dammit—come back.…”

The agitated voice thinned, became distant then merged into that same whirling, rushing sound which had accompanied the fall through the tunnel and, indeed, I was falling through the tunnel again, being whelmed breathlessly away into darkness.

* * * *

“How are you feeling now, my good man?” asked the man in the frock coat who seemed to appear out of nowhere. “You’ve taken a bad turn, but at least it’s not the cholera.”

I was sitting in a chair and the elderly man in the frock coat was hovering over me. I saw a woman in a white cap and with a white apron over her crinoline go past. At least I was in surroundings I understood, away from nightmarish explosions, fires, and men in grotesque clothing, struggling against a hellish background.

“Where…?” I started.

“Where are you?” finished the elderly man. “Why in the St. Giles Cholera Hospital, where we’re doing the best we can in this awful epidemic. A charitable gentleman saw you staggering in the street near Moon Lane, thought at first you had been imbibing, then felt you had fallen victim to the cholera. He put you in his carriage and brought you here. I’m a doctor and you plainly haven’t caught the disease, though you’ve been here the better part of the day, delirious and mumbling. There’s no sign of any drink on you, but you look as if you’ve had a hard time of it. Not been attacked by one of those street ruffians, have you? You have a cut on your face which we dressed with a strip of court plaster and generally cleaned you up.”

I felt my face and discovered that my false beard and moustaches had somehow become lost. I was still in my disguise as a workingman and hoped that was what the doctor took me for. I assured him I had recovered and was able to make my way home and he, kindly man, fortified me with a glass of brandy and water before allowing me to leave.

For a couple of days, I kept to my rooms, recovering my strength and wondering about the strange and alarming bout of delirium I had endured. But was it really delirium?

I kept an eye on the papers and on the second day, saw a paragraph stating that the landlord of a set of warehouses in Moon Lane was seeking one of his tenants who had unaccountably gone missing. He was a Mr. Chaffin, a gentleman of reclusive nature who was apparently engaged on some kind of scientific research.

And of M. Auguste Duclois I had no word. He did not appear on the appointed day to pay me the remainder of my fee, but then I had hardly earned it.

A week after my strange experience, the ever-helpful newspapers gave me startling information. It concerned the fatal explosion of the boilers of the steam packet Lily of France en route to Dieppe, one of the shocking tragedies of 1855. Among the list of dead passengers was the name of M. Auguste Duclois, known for his somewhat eccentric contributions to scientific studies.

This gave me pause. It looked as if he was hastily departing the shores of England. Could it be that, alerted by news of the search for Amos Chaffin, he took fright thinking that someone who knew of his bitter opposition to Chaffin might go to the police with the suggestion that he had something to do with the disappearance?

Hoping that if anyone saw a youngish man in rough clothing and with a scrubby beard and moustaches entering the warehouse in Moon Lane just before Chaffin’s disappearance, they would not identify him as myself, I lay low for a spell.

I hoped, too, that the next client to come along would be as liberal with his funds as the much-lamented M. Auguste Duclois.

Extract from a letter written in 1965 by Mr. Kenneth Spence to his friend Mr. Jim Morton. Mr. Spence, a retired Chief Superintendent of the Metropolitan Police, died four years later. He joined the police service in 1922 and retired in 1952. During the London blitz of 1940 onwards, as an Inspector, he had charge of a large portion of central London, coordinating operations between the police and the various branches of the Civil Defense services.

Mr. Morton was his lifelong friend from schooldays. Although a chartered accountant by profession, during the Second World War he was a Column Officer in the Auxiliary Fire Service and by coincidence, carried out his duties in the area of London covered by Inspector Spence Mr. Morton died in 1973.

Dear Jim,

A couple of letters ago, you mentioned that strange affair of the corpse in old-fashioned clothing taken from a burning building in Moon Lane by your chaps and the rescue people during the Blitz at Christmas 1940. You’ll remember how his get-up made us think at first that he might have come from some panto or Dickensian show but, by then, the Blitz had reached such intensity that even the bravest of brave showbiz people had closed up shop. A story went about that someone else in antique clothing was seen in the region and one of my bobbies swore he’d met him and spoken to him while both were sheltering in a doorway. He even gave me a description of him, but he was never traced. Ever afterwards, the PC claimed he’d met a ghost.

“You’ll no doubt remember Moon Lane. It was all but falling in when Goering’s people flew over to demolish it. All that area of London was razed and redeveloped by London County Council long before, but Moon Lane somehow lingered on, though it was scheduled to be demolished when the war stopped all slum clearance. Such a place might well be haunted.

“As for that corpse, many aspects of it were truly odd and I don’t think I ever told you about all of them. You’ll remember dropping me a private note, saying you found his costume and sidewhiskers and everything else about him strange. Because of the pressures of the Blitz, we could not hold inquests and burial was usually quick and without real investigation, but your note caused me to drop in at the emergency mortuary to see the body. As you told me, he was a middle-aged man, pockmarked and, even naked as he was when I saw him, he looked distinctly old-fashioned.

“I was lucky in that old Jock McAllen was in charge of the mortuary. He was a veteran pathologist who came out of retirement to help in the emergency. He’d had an unusual career, starting out in dentistry, then changing to surgery. However, he kept up an interest in the history of dentistry and had written a book on it.

“Looking over the body with me, he said he was baffled by the fact that all the clothing was of a style around a century before. He even had antique underwear. A couple of Queen Victoria sovereigns and some pennies and silver, all dated around the 1840s and 1850s, were found in his trousers pocket, and Jock kept them to hand over to the police.

“‘You’ll notice his pockmarks,’ said Jock. ‘That was typical in the middle of the last century. Smallpox was common and a great many people recovered from it but were marked for life. But it’s the teeth—those false teeth—that intrigue me. There’s no doubt, Inspector Spence, that they’re Waterloo teeth!’

“I asked what Waterloo teeth were and he told me that, when creating false teeth was an imperfect art, there was a demand for real teeth to be used—sound teeth from young corpses. Because so many soldiers of all sides killed at Waterloo in 1815 were mere youths, there was afterwards a wholesale digging up of corpses, and ‘Waterloo teeth’ were manufactured all over Britain, France, and Belgium. Old Jock said that, even late in the century, people were chewing with the teeth of young men killed in 1815.

“‘A man of 1940’, said old Jock, ‘might deck himself out in the full costume of the nineteenth century and, by coincidence, even be heavily pockmarked, Inspector, but is he likely to wear a set of waterloo teeth, even if he inherited them from his great grandfather? Frankly, I’m totally bewildered’.

“And so am I, Jim. I’ve been bewildered all these years. It was as if the man had been somehow transported from the middle of the nineteenth century to the thick of our turmoil in 1940. But that is utterly impossible. Well, it is. Isn’t it…?”