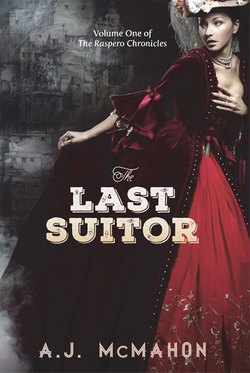

Читать книгу The Last Suitor - A J McMahon - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTWO

The Proposal of Lord Percival Breckenridge

to Lady Isabel Grangeshield

3:20 PM, Monday 2 May 1544 A. F.

Isabel Grangeshield sat contentedly in her magnificent garden, her fan held lightly in her hands as she contemplated the world at large. The sky was as blue as blue could be, with fluffy white clouds moving across it like clots of cream sliding down the sides of a bowl. Behind her, Grangeshield House rose up into the air like a ship surging through the blue sky overhead, the Grangeshield banner with its two red lions waving in the gentle breeze.

Isabel was looking her best, which was to say formidable. Her dark brown hair had been carefully coiled into a spiral pattern held together by green and white gemstones which had been carefully chosen to augment the dark green dress she was wearing. This dress was cut low to display the cleavage of Isabel’s large breasts, then pulled in tight at the waist in order to balloon into cascading skirts which only ended their fall in order to display the demure tips of two shoes peeking forward where they were positioned on the ground. Isabel’s large warm brown eyes were framed by darkened eyelashes, her full lips painted a deep red, her rounded cheeks gently rouged to emphasise the sweetness of her face, her bare neck and shoulders gleaming in the sunlight as she sat straight-backed in her chair on this day on which her latest suitor would propose to her.

Beside her sat Lord Percival Albert James Algernon Breckenridge, Count of Anthored, Keeper of The Sixth Key, Knight Exalted of the Council of Rondreth, and the fifth richest man in Anglashia. He cut a striking figure, with a magnificent moustache and carefully combed reddish hair, blue eyes and the proportions of his nose, mouth and brow all combining to form the regular and pleasing features of his handsome face. His clothes were a glorious fusion of blue and yellow, his ancestral colours, from the gleam of his highly polished shoes to the faded sheen of the carefully folded scarf around his neck.

Isabel and Percival were seated in the ornately carved Grotto of Peace on red velvet cushions at right angles to each other. Discreetly out of earshot at some distance away to Isabel’s left sat Lord and Lady Easton in chairs placed within the hexagonal Pavilion of the Sun. With them were Lady Breckenridge, the mother of Percival, and Percival’s bored younger brother, the seventeen year-old William. The tableau was not set by accident, for there was a design to it, and the centerpiece of the design were the two figures of Isabel and Percival.

Isabel sat composedly, her hands in her lap holding her fan, which she twirled now and then. Percival himself was anything but composed, fidgeting in his chair continually, straightening in his chair and then slouching down, his legs crossed, the heel of his right foot occasionally tapping at his left calf.

They had exchanged pleasantries, enquired after each other’s health and also after the health of various relatives and friends. They then both expressed concern about the international situation, which was bad, as usual. Percival had then spoken at length about harmony, mutual understanding and the merging of destinies. He appeared to have memorised certain quotes because his eyes would slightly glaze over at times as he brought forth segments of highly polished prose containing the wit and wisdom of the ages. Isabel nodded as if attentive to everything he said, the picture of an appreciative audience. In point of fact, she was hardly listening to a word he was saying, but she was enjoying herself nonetheless.

She always enjoyed being proposed to no matter who the suitor in question was. They were all one to her because she had absolutely no intention of accepting any of their proposals. She was twenty two years old and frequently badgered about getting married by her guardians, Lord and Lady Easton, but she was not getting married for several reasons. One was that she enjoyed her independence, another that she enjoyed being chased after by every eligible bachelor in New Landern, and another was that she had never yet met a man who she wanted to marry.

She knew that the Eastons had particular hopes for this match. Percival was twenty-eight, good-looking with a very handsome moustache, from one of the noblest families in the land and incredibly rich. They felt that this match had everything going for it, including the undeniable fact that it was definitely time for Isabel to get married. While never complaining about their own roles as chaperones, it could not be denied that this was also part of their reasoning. They would then have their own time back to themselves rather than being obliged to be Isabel’s guardians, but to their credit this was a secondary consideration for them.

Percival had fallen silent for some time while Isabel had patiently waited.

‘Isabel,’ Percival said, ‘well, here we are.’

Isabel saw that he was getting his nerve together to make his proposal. She always enjoyed this part. Her suitors varied in their degrees of anguish, and they each took their varying times about working themselves up to the moment of truth, but when the time came she took a certain interest in watching them go about what they had to do. The sight of the pain, her suitors were going through gave her a warm and pleasurable feeling. She said nothing, her eyes demurely downcast, twirling her fan in her hands.

‘So here we are, are we not, Isabel?’

‘Yes, we are here, Percival,’ Isabel said calmly.

‘So,’ Percival continued, ‘we are here, are we not?’

Isabel looked down at the fan in her hands, peeking up at Percival now and then.

‘Yes, we are here,’ Percival said, ‘and here we are.’

Isabel unfolded her fan and studied the elephant drawn on its opened expanse. The elephant had its trunk upraised as if trumpeting. Isabel wondered what kind of noise an elephant made when it was trumpeting. Was it like a trumpet? Was that why the word trumpeting was used? What kind of word was trumpeting anyway?

‘Isabel,’ Percival said, ‘there comes a time when a man must decide on questions of the utmost seriousness. This is a momentous occasion, a time of solemnity, a collision of destinies.’ He paused to take a deep breath.

Isabel thought that the phrase a collision of destinies wasn’t bad. She hadn’t heard that one before. She thought that a momentous occasion was an over-used phrase, though, so Percival lost marks there.

‘There comes a time in the life of a man, Isabel,’ Percival continued, obviously reaching into his memory for a rehearsed set of words, ‘when the pleasures and comforts of the day are not enough, when his soul thirsts for something of which he knows not, when beyond what he sees and understands he hears the call of the unknown seeking an answering call to a question he dares not ask.’

Isabel was very pleased with all this. It was excellent. Percival was doing very well. At this rate, she would give him very high marks for his performance.

‘You understand me all too well, I fear, my sweetest Isabel,’ Percival said, looking at her closely. ‘Do you not, my sweetest Isabel?’

Isabel noticed that he had called her my sweetest Isabel twice in the same breath. She could tell he was not far away from his proposal by now.

‘I am all at a loss to understand you, Percival,’ she said hesitantly, folding up her fan. ‘You speak of such high and lofty things that my head spins merely to dare to comprehend matters of such deep import. Oh, you must help me to understand these matters of which you speak. On my own I cannot.’

Percival stroked his magnificent moustache while he pondered her reply. This wasn’t the answer he had hoped for. He had hoped that she would have gotten the drift by now, thus helping him over the last hurdle of actually proposing. It was still going to be uphill for a while longer, Percival realised. But the blood of kings, adulterous archbishops and countless counts flowed in his veins, and he manfully squared up to the challenge. ‘It falls to my duty to do that which I gladly take up with a shout of joy,’ he said.

Isabel wondered if Percival had got that right. Hadn’t he misquoted Courtlyn? It didn’t sound right, somehow. ‘Your eloquence is beyond compare, Percival,’ Isabel said in a tone of the deepest admiration. ‘How do you express your thoughts with such a fluid and elegant turn of phrase?’

‘Ah,’ Percival said meaningfully, ‘my words fly on wings sent from the deepest least wayward impulses of my heart.’

Well, he got that quote right, Isabel thought, recognising the line from Dacian’s epic poem of the love between the mermaid and the doorkeeper of the great castle by the sea.

‘So that is why,’ Isabel commented. ‘But still I cannot understand what it is that you wish me to understand.’

Percival swallowed back the annoyance which had momentarily arisen on hearing her words. How many times, he thought, did he have to use such phrases as impulses of my heart before his beloved comprehended the import of his discourse? ‘What it is that you must understand,’ he said, ‘is that however we fly on the wings of our mind, it is the earth that pulls us downward.’

Lorene, Isabel noted, another quote which Percival had actually got right. ‘You must think very badly of me,’ Isabel said, ‘but still I do not understand.’

‘Isabel, dearest, my dearest sweetest Isabel, sweet, sweet Isabel, I wish you to be mine, I want to travel hand in hand with you along the great journey of life, together, your hand in mine, I am yours for all of eternity, dearest Isabel, will you grant me that which is in your keeping and all that I desire?’

Isabel realised she couldn’t play dumb for much longer. She thought that the sentence I want to travel hand in hand with you along the great journey of life was actually not too bad. She memorised it in order to tell her friends later. She wondered if Percival had thought it up by himself or if he’d had help.

‘Goodness!’ Isabel gasped, raising her hand to her mouth, ‘can it be so? But what are you saying, Percival? Surely I mistake what you say!’

‘No, beloved Isabel,’ Percival assured her, ‘I wish you to marry me and be mine for ever.’

So he had finally got to it, Isabel observed. He had used the word marry which as far as she was concerned was the actual proposal itself. She noted that he hadn’t actually gotten onto his knee and proffered a ring, which brought his marks down as far as she was concerned, because she always liked that touch; she liked to see a man on his knees before her. Still, she reflected, he hadn’t done too badly. Even his nervousness had been an artistic enhancement of the overall presentation, even if unintentional. She liked to see a man tremble at the thought of asking her to marry him, because, after all, she expected no less.

Now came Isabel’s favourite part, namely her refusal of the proposal. A well-made proposal deserved a gracious refusal; a proposal less deserving of her favour called forth a much blunter response. Percival, she decided, had earned a gracious refusal.

‘This is all so sudden and unexpected!’ Isabel gasped, unfolding her fan and raising it in front of her face. ‘I am caught by surprise. I do not know what to say.’

‘Say yes, sweetest Isabel,’ Percival urged her.

Isabel said immediately, ‘Oh, but you give me no time! Surely I may have time to think.’

‘You may have all the time in the world, sweetest Isabel,’ Percival told her, ‘for what are the minutes you take now, compared with all the years to come?’

Isabel noted that he had given her only minutes, which she thought mean of him; also, she couldn’t help but note that he had equated minutes with all the time in the world, which hardly seemed logical. She also couldn’t help but feel that the phrase the years to come had the slightly depressing connotation of a prison sentence to it, at least to her ears.

‘But how can I say yes when I do not love you?’ she said. ‘Surely it is on the foundations of love that marriage is built?’

Percival took this in his stride. He was prepared for this one. ‘Love will grow in time, sweet Isabel. We will grow to love each other as the plant grows towards the sun.’

Isabel approved of that line. It wasn’t too bad. ‘But in darkness the plant shrivels and dies,’ she said. ‘And what then?’

Percival was thrown by this. He had no idea what to say. He wasn’t prepared for this response. Isabel gazed wide-eyed at him while he thought this one over. ‘The plant is just a metaphor,’ he said eventually, obviously wishing he had chosen another metaphor. ‘Never mind plants. We will come to love each other anyway.’

‘Percival, you have granted me the greatest honour I could ever have wished for,’ Isabel said admiringly, in tones of the deepest sympathy she could reach for as she warmed up for the kill. ‘You have asked for my hand in marriage and by doing so you have gained my deepest attention and most ardent goodwill. Yet, I must refuse your proposal for I cannot see that we are to be together in the way that you seek. I must say no, Percival, no to the proposal which you have made. I refuse your proposal of marriage.’

Isabel looked at Percival, who looked back at her.

Percival opened his mouth to say something, then closed it again; he thought for a while, then opened his mouth as if to speak, then seemed to think better of it and closed his mouth again. Isabel watched all this with a certain disinterest. For her, the drama was all over, and it was time to wrap this all up and move on.

‘So, you are saying no?’ Percival queried eventually.

‘Exactly!’ Isabel said, careful not to say it too sharply. ‘I am refusing your proposal.’ In her experience, which was considerable, suitors very often refused to take no for an answer and pestered her to change her mind, and that was when she could turn nasty. But at this stage, a firm hand was usually all that was needed.

‘Well, naturally I am disappointed,’ Percival said. ‘I had hoped you would accept my proposal.’

Isabel couldn’t help but think that Percival did not exactly look heartbroken. He did not even look particularly disappointed. She wondered if he had ever really wanted to marry her at all. Perhaps this course of action had been urged on him by his mother and his financial advisers.

‘I have refused your proposal,’ Isabel told him gently, ‘and that is the end of the matter. I know you are such a complete gentleman that you will not press your suit further.’

‘Yes, quite,’ Percival agreed, but he did not yet look ready to give up. ‘I understand, of course, proposal, refusal, yet I cannot help but wonder if in the fullness of time there might come to be a change which, though gradual and imperceptible in the onset of its influence, might yet bring about such a shift as to render all my hopes fulfilled beyond all measure by that which is only a delay of our mutual happiness.’

Isabel’s hands had tightened on her fan during this speech. If Percival had been a more observant man, he might have recognised that as a danger sign, but Percival saw nothing. ‘I will not receive a second proposal from you, Percival,’ Isabel said gently, ‘so it is futile to hope I will change my mind. My mind is perfectly made up. There is nothing more to be said.’ She spoke so plainly as to be quite deliberately blunt.

‘Yes, quite,’ Percival said without moving. ‘That is just so. But if the ardour of my suit is to be tested by obstacles which must be surmounted, yet I assure you I am not daunted by any tests I may be obliged to undergo, no matter how plainly I am told these obstacles are impassable.’

Isabel took the tip of her fan in the palm of her left hand, which she held upright with the other end of the fan in her right hand as if it was a dagger. ‘I am starting to question whether you are a gentleman, Lord Breckenridge,’ she told him coldly.

This stung Lord Percival Breckenridge like a wasp up his nostril. He straightened up in his chair and said, ‘I beg your pardon?’

‘Your suit is not welcome,’ Isabel told him with an edge of fierceness to her voice. ‘If you are a gentleman, then accept my refusal with decorum. If you persist in pressing your suit, I shall have no choice but to draw the only appropriate conclusion which can be drawn from the persistence of your unwelcome attentions.’

Percival looked as if she had just hit him several times, which in a sense she had. He was sitting rigidly upright now, his silver-topped walking cane motionless in his right hand. He looked quite pale. ‘Of course I will no longer press my attentions upon you if they are unwelcome,’ he said. ‘I only sought to make you an offer of marriage because of your wholly admirable qualities. I did not expect to be insulted in return.’

‘I do not insult you, Percival,’ Isabel told him gently, ‘but I refuse your proposal and I ask you as the complete gentleman which you undoubtedly are to accept my refusal of your proposal without further argument.’

Percival nodded several times without speaking. ‘Yes, quite,’ he said, but still to Isabel’s growing exasperation he made no move to get going. ‘I understand that you have refused this proposal. It is just that I wonder if you might accept another proposal at some future date.’

‘No, I will not,’ Isabel told him with a careful blend of three-parts severity with seven-parts gentleness. ‘I ask you not to be so discourteous as to trouble me again about a matter which is already settled beyond question.’

‘Yes, quite,’ Percival said, still not accepting defeat. ‘Yet I cannot help but hope even now, in the depths of despair, in the darkness of my disappointment, that a light may shine forth to guide me to our shared happiness.’

Isabel then lost her temper. She stood up, walked some steps away, turned to face Percival, and shouted at the top of her voice, ‘Your attentions are unwelcome, Lord Breckenridge!’

This public spectacle had the effect that she knew it would. The Eastons, Lady Breckenridge and Percival’s younger brother William, no longer looking bored, but his eyes alight with mischief and joy, all jumped up from their chairs and came running over to join them.

‘But what is the matter, Isabel?’ Lady Dacia Easton asked with concern.

‘Lord Breckenridge has proposed marriage. I have refused his proposal. Yet, he persists in continuing to press his suit. I am simply fed up with his behaviour. What kind of man is he to behave like this?’

Percival stood up because everyone else was standing around him, leaving him feeling dwarfed and said, ‘Ah, yes, I was merely suggesting that I might make a second proposal at some later date.’

‘That sounds very sensible,’ Lord Bentley Easton said approvingly. ‘Naturally the first proposal is very often refused. It shows nothing but a becoming modesty on the part of the maiden, and it is only to be expected that a second proposal will be proffered.’

‘Look at Lord and Lady Preece,’ Lady Easton said, backing up her husband. ‘She turned him down six times!’

‘I am glad to find I am not alone in this matter,’ Percival said with some relief, ‘for Isabel has suggested I am not a gentleman for continuing to press my suit.’

‘Isabel!’ Lady Easton gasped, shocked. ‘You said no such thing!’

‘I certainly said no such thing, Aunt Dacia,’ Isabel replied. ‘Lord Breckenridge misrepresents me. I said that if he continued to pester me with his unwelcome attentions I would be forced to conclude that he was not a gentleman.’

‘If you were to reach such a conclusion, Lady Grangeshield,’ Percival said icily, ‘I would be obliged to demand satisfaction. Would there be someone to act on your behalf if so?’

‘I am sure there is no need for such an action on your part, Percival,’ Lord Easton said hastily, trying to hose everything down before the fire spread.

‘There is most certainly not!’ Lady Breckenridge agreed forcefully, giving Isabel a less than friendly look.

‘In the event that you demand satisfaction, I would make enquiries as to who might act on my behalf,’ Isabel told him with equal iciness, knowing full well that half of New Landern would jump forward to defend her. ‘You will no doubt scorn to refer to First Combat but will refer to a higher grade.’

‘Percival will do no such thing!’ Lady Breckenridge shouted on the instant.

‘First Combat would be the appropriate form of satisfaction for such an offence as this, which in any case has not even been given yet, and will not be,’ Lord Easton said firmly, giving Isabel a hard look. He did not often put his foot down, but he was doing so now.

‘May I enquire of Lord Breckenridge,’ Isabel said coldly, looking directly at Lady Breckenridge as he said this, ‘why he cannot comprehend that I have refused his proposal today and I do not wish him to trouble me again with another? I do not want to marry Lord Breckenridge. Not today, not tomorrow, not ever. How much more plainly do I need to speak?’

‘Let us agree that there is nothing more to be said about this matter today,’ Lord Easton said hastily while Lady Breckenridge was pondering her response.

‘It is very becoming of you to be so modest,’ Lady Easton said, muddying the waters at a time when Isabel was trying to make everything crystal clear. ‘You are fighting like a tigress to defend your modesty, and what could be more commendable?’

Lord Easton was infuriated by his wife’s blunder but even as he was opening his mouth to speak Percival made his own blunder.

‘Ah, I thought so,’ he said, nodding with an air of self-satisfaction, ‘your modesty is to be commended, Isabel, and I will return to propose again.’

‘You are not a gentleman, Lord Breckenridge,’ Isabel said very clearly and forcefully.

Silence gripped the group then. Lady Easton turned to look at her husband only to see him glaring at her with such cold fury she immediately turned away again, wondering why he was so angry with her. She hadn’t said anything.

Percival went pale and couldn’t speak. He looked at Isabel to see her glaring at him with a hard, fixed look on her face that was so rigid it made her face appear like a mask.

‘I must demand satisfaction, Lady Grangeshield,’ Percival said eventually. ‘Is there anyone who will act on your behalf?’

‘Name the time and place of the duel and your opponent will be there,’ Isabel told him, furious to the tips of her fingers. ‘What form of satisfaction do you require?’

‘First Combat,’ Percival said. ‘Tomorrow at six o’clock at Mildgyd.’

‘Very well,’ Isabel said. ‘I would like to take this opportunity to make something quite plain to you, Lord Breckenridge. If you ever propose to me again, I will tell you again quite plainly that you are not a gentleman and you will find yourself fighting another duel. That duel will not be First Combat, which you will already have referred to once. Is that clear? Now get out! You are not welcome here and you are never welcome to ever set foot here again!’ With that Isabel turned and stalked furiously away back to the house.

The Eastons tried to make their farewells as courteously as they could, but the Breckenridges were not to be mollified in any way, no matter how much soothing oil Lord Easton tried to pour on these troubled waters. William had a barely concealed and delighted grin; he had enjoyed the show and now he had a duel to look forward to the very next day. Life did not get any better than this, William thought.

Isabel stormed up to the Red Drawing Room and threw herself down in her favourite chair. What an impossible man! she thought furiously to himself; it seemed he was so conceited he could not believe she did not want him as her husband. Well, he would grasp that concept fully when he faced his opponent in the duel tomorrow.

She turned her mind then to selecting someone to act on her behalf. She was glad that in her temper she had not pushed the issue further to be a matter of second or final combat. First combat was one thing, second or final combat another. It would be much easier for her to find someone to act on her behalf in a lesser duel. As the Eastons entered the room, she held up her hand palm out to keep them at bay. They sat nearby with expressions of resignation on their faces.

Isabel made her choice, went to her study to write a letter to the lucky man and dispatched it immediately by private messenger. Lewis Hexton was so excited as to come around immediately, and his repeated expressions of delight at being her champion made it plain he was wondering whether to propose to her again. Isabel neither encouraged nor dispelled his illusions, deciding she would not tell him that she would not receive his suit a second time until after the duel was over.

6:00 PM, Tuesday 3 May 1544 A. F.

The duel of First Combat was fought as promised at Mildgyd, in front of a large audience. The duelists faced off against each other, each with four mobile karns floating around them and their fight began. To be brought down onto the ground was to lose the round and there were three rounds in First Combat. There was only one round in Second Combat because that required the breaking of at least one limb. There was also only one round in Final Combat because that required a magnetised disc being used to kill the opponent.

The two men circled each other, wands in hand, slashing ineffectually with various combinations, the one nearly toppling the other and then nearly being toppled in turn. At one point Lord Breckenridge was brought down by physical contact, which was a foul; three fouls would mean the loss of the round. After some twenty minutes or so Lord Breckenridge managed to bring down his opponent with a stray mobile karn that grabbed an ankle and tugged him off-balance so that he fell down. His supporters cheered and Lord Breckenridge, his hair tousled and breathing heavily, nodded briefly in acknowledgement of this support. Then the duel resumed and Hexton in a reckless frenzy attacked so wildly that as much by chance or at least brute force, he brought Breckenridge down. It was now the third round and both men were wary now, for the next victory was decisive. They slashed and grappled each other hesitantly, trying out all the combinations they knew, striking and blocking and parrying all they could. They were both breathing heavily now, their hair matted with sweat. The duel had been going on for fifty minutes or so. Then Breckenridge threw everything he had into a sudden rush that went on without stop while his opponent blocked and parried until overcome by an overwhelming flurry of combinations he lost his footing and fell, leaving Breckenridge standing with his wand upraised in triumph. The cheers of his supporters were deafening.

Isabel was satisfied with the outcome. Her champion had been defeated, which meant she could treat him with disdain for failing to give her victory. There was no need to trouble herself further with his attentions; she could tell him to get lost in the politest but most unmistakable of ways. Breckenridge had by now grasped the concept that he was a rejected suitor, which damaged his pride, but his victory in the duel would go a long way to healing the wound to his pride. He could now walk around New Landern with a victorious swagger and in time he would be merely yet another of her rejected suitors, who were now growing in numbers to the point that there were even jokes being told in New Landern that Isabel’s rejected suitors should form a club whose membership criterion would be precisely this status.

Breckenridge and Hexton were now shaking hands and exchanging words. They were smiling at each other and discussing key points of the fight they had just had. What they were saying could not be heard as they were too far away, but it was obvious that neither could praise the honourable bravery of his opponent enough. They knew each other to talk to in passing, of course, but they had never been especially close up until now. They would very likely get drunk together tonight and remain fast friends for life from the looks of how happy they were with each other’s company.

All in all, Isabel reflected, everything had ended well.